Toxicological Profile for Cyanide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mechanistic Insights Into the Hydrocyanation Reaction

Mechanistic insights into the hydrocyanation reaction Citation for published version (APA): Bini, L. (2009). Mechanistic insights into the hydrocyanation reaction. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. https://doi.org/10.6100/IR644067 DOI: 10.6100/IR644067 Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2009 Document Version: Publisher’s PDF, also known as Version of Record (includes final page, issue and volume numbers) Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

Numerical Simulation of a Two-Phase Flow for the Acrylonitrile Electrolytic Adiponitrile Process in a Vertical/Horizontal Electrolysis Cell

energies Article Numerical Simulation of a Two-Phase Flow for the Acrylonitrile Electrolytic Adiponitrile Process in a Vertical/Horizontal Electrolysis Cell Jiin-Yuh Jang * and Yu-Feng Gan Department of Mechanical Engineering, National Cheng-Kung University, Tainan 70101, Taiwan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +886-6-2088573 Received: 7 September 2018; Accepted: 6 October 2018; Published: 12 October 2018 Abstract: This paper investigated the effect of oxygen holdup on the current density distribution over the electrode of a vertical/horizontal electrolysis cell with a two-dimensional Eulerian–Eulerian two-phase flow model in the acrylonitrile (AN) electrolytic adiponitrile (ADN) process. The physical models consisted of a vertical/horizontal electrolysis cell 10 mm wide and 600 mm long. The electrical potential difference between the anode and cathode was fixed at 5 V, which corresponded to a uniform current density j = 0.4 A/cm2 without any bubbles released from the electrodes. The effects of different inlet electrolyte velocities (vin = 0.4, 0.6, 1.0 and 1.5 m/s) on the void fraction and the current density distributions were discussed in detail. It is shown that, for a given applied voltage, as the electrolyte velocity is increased, the gas diffusion layer thickness decreased and this resulted in the decrease of the gas void fraction and increase of the corresponding current density; for a given velocity, the current density for a vertical cell was higher than that for a horizontal cell. Furthermore, assuming the release of uniform mass flux for the oxygen results in overestimation of the total gas accumulation mass flow rate by 2.8% and 5.8% and it will also result in underestimation of the current density by 0.3% and 2.4% for a vertical cell and a horizontal cell, respectively. -

Transport of Dangerous Goods

ST/SG/AC.10/1/Rev.16 (Vol.I) Recommendations on the TRANSPORT OF DANGEROUS GOODS Model Regulations Volume I Sixteenth revised edition UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2009 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ST/SG/AC.10/1/Rev.16 (Vol.I) Copyright © United Nations, 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may, for sales purposes, be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the United Nations. UNITED NATIONS Sales No. E.09.VIII.2 ISBN 978-92-1-139136-7 (complete set of two volumes) ISSN 1014-5753 Volumes I and II not to be sold separately FOREWORD The Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods are addressed to governments and to the international organizations concerned with safety in the transport of dangerous goods. The first version, prepared by the United Nations Economic and Social Council's Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods, was published in 1956 (ST/ECA/43-E/CN.2/170). In response to developments in technology and the changing needs of users, they have been regularly amended and updated at succeeding sessions of the Committee of Experts pursuant to Resolution 645 G (XXIII) of 26 April 1957 of the Economic and Social Council and subsequent resolutions. -

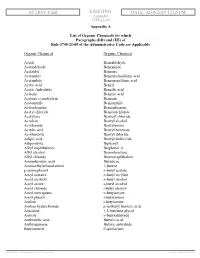

02/06/2019 12:05 PM Appendix 3745-21-09 Appendix A

ACTION: Final EXISTING DATE: 02/06/2019 12:05 PM Appendix 3745-21-09 Appendix A List of Organic Chemicals for which Paragraphs (DD) and (EE) of Rule 3745-21-09 of the Administrative Code are Applicable Organic Chemical Organic Chemical Acetal Benzaldehyde Acetaldehyde Benzamide Acetaldol Benzene Acetamide Benzenedisulfonic acid Acetanilide Benzenesulfonic acid Acetic acid Benzil Acetic Anhydride Benzilic acid Acetone Benzoic acid Acetone cyanohydrin Benzoin Acetonitrile Benzonitrile Acetophenone Benzophenone Acetyl chloride Benzotrichloride Acetylene Benzoyl chloride Acrolein Benzyl alcohol Acrylamide Benzylamine Acrylic acid Benzyl benzoate Acrylonitrile Benzyl chloride Adipic acid Benzyl dichloride Adiponitrile Biphenyl Alkyl naphthalenes Bisphenol A Allyl alcohol Bromobenzene Allyl chloride Bromonaphthalene Aminobenzoic acid Butadiene Aminoethylethanolamine 1-butene p-aminophenol n-butyl acetate Amyl acetates n-butyl acrylate Amyl alcohols n-butyl alcohol Amyl amine s-butyl alcohol Amyl chloride t-butyl alcohol Amyl mercaptans n-butylamine Amyl phenol s-butylamine Aniline t-butylamine Aniline hydrochloride p-tertbutyl benzoic acid Anisidine 1,3-butylene glycol Anisole n-butyraldehyde Anthranilic acid Butyric acid Anthraquinone Butyric anhydride Butyronitrile Caprolactam APPENDIX p(183930) pa(324943) d: (715700) ra(553210) print date: 02/06/2019 12:05 PM 3745-21-09, Appendix A 2 Carbon disulfide Cyclohexene Carbon tetrabromide Cyclohexylamine Carbon tetrachloride Cyclooctadiene Cellulose acetate Decanol Chloroacetic acid Diacetone alcohol -

UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE PROCESS of PREPARING 2,2-DIPHENYL-3- TRILEMETHYL-4-Dimethylamino-BUTYRONI Earl M

Patented Aug. 19, 1952 2,607,794 UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE PROCESS OF PREPARING 2,2-DIPHENYL-3- TRILEMETHYL-4-DIMETHYLAMINo-BUTYRONI Earl M. Chamberlin, Rahway, and Max Tishler, Westfield, N.J., assignors to Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, N.J., a corporation of New Jersey No Drawing. Application April 9, 1949, Seria No. 86,596 6 Claims. (CL 260-465) . 2 This invention relates to the manufacture of dimethylamino-butyronitrile (compound 5). Compounds possessing analgesic and anesthetic These reactions may be chemically represented action. In particular, it is concerned with an as follows: improved synthetic method for preparing 2,2-di phenyl 3-methyl-4-dimethylamino - butyronia CH3CHOHCHCl + RSO: C1 - cHipHCHCI trile and With novel chemical compounds useful Öso, R. as intermediates in the preparation of this come (1) (2) (3) pound. , 2,2-diphenyl-3-methyl - 4-dimethylami (C6H5)2CHCN no-butyronitrile is itself an important interne NaNH diate in the Synthesis of isoamidone, 1-dimethyl O amino-2-methyl-3,3-diphenylhexanone - 4 and (CH3)NH SaltS thereof. ISOamidone and its salts possess (C.H.)--HCH.N(CH), --- (CH)--HCH.Cl analgesic action and may be used as substitutes CE CH: for morphine. - N N 2,2-diphenyl-3-methyl - 4 - dimethylamino 5 (5) (4) butyronitrile has been prepared previously by The organic Sulfonyl chloride employed in the reacting 1-dimethylamino-2-chloropropane with foregoing reaction can be either an aromatic diphenylacetonitrile as described by Schultz et al. Sulfonyl chloride such as p-toluene sulfonyl chlo (J. A. C. S. 69, 188-189, Jan. 1947). As pointed ride, benzene Sulfonyl chloride and the like, or out by these workers, however, when 2,2-di 20 an aliphatic Sulfonyl chloride such as methane phenyl - 3 - methyl - 4-dimethlamino-butyroni Sulfonyl chloride. -

Synchronous Fluorescence Spectroscopic Study Of

Spectrochimica Acta Part A 79 (2011) 1034–1041 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/saa Synchronous fluorescence spectroscopic study of solvatochromic curcumin dye ∗ Digambara Patra , Christelle Barakat Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, American University of Beirut, P.O. Box 11-0236, Riad El Solh, Beirut 1107-2020, Lebanon a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Curcumin, the main yellow bioactive component of turmeric, has recently acquired attention by chemists Received 1 July 2010 due its wide range of potential biological applications as an antioxidant, an anti-inflammatory, and an Accepted 13 April 2011 anti-carcinogenic agent. This molecule fluoresces weakly and poorly soluble in water. In this detailed study of curcumin in thirteen different solvents, both the absorption and fluorescence spectra of curcumin Keywords: was found to be broad, however, a narrower and simple synchronous fluorescence spectrum of curcumin Curcumin was obtained at = 10–20 nm. Lippert–Mataga plot of curcumin in different solvents illustrated two Solvent polarity E sets of linearity which is consistent with the plot of Stokes’ shift vs. the 30. When Stokes’s shift in SFS T wavenumber scale was replaced by synchronous fluorescence maximum in nanometer scale, the solvent max E polarity dependency measured by SFS vs. Lippert–Mataga plot or T30 values offered similar trends as max measured via Stokes’ shift for protic and aprotic solvents for curcumin. Better linear correlation of SFS vs. -

Purification and Characterization of a Novel Nitrilase of Rhodococcus

JOURNAL OF BACTERIOLOGY, Sept. 1990, p. 4807-4815 Vol. 172, No. 9 0021-9193/90/094807-09$02.00/0 Copyright X3 1990, American Society for Microbiology Purification and Characterization of a Novel Nitrilase of Rhodococcus rhodochrous K22 That Acts on Aliphatic Nitriles MICHIHIKO KOBAYASHI,* NORIYUKI YANAKA, TORU NAGASAWA, AND HIDEAKI YAMADA Department ofAgricultural Chemistry, Faculty ofAgriculture, Kyoto University, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606, Japan Received 18 April 1990/Accepted 8 June 1990 A novel nitrilase that preferentially catalyzes the hydrolysis of aliphatic nitriles to the corresponding carboxylic acids and ammonia was found in the cells of a facultative crotononitrile-utilizing actinomycete isolated from soil. The strain was taxonomically studied and identified as Rhodococcus rhodochrous. The nitrilase was purified, with 9.08% overall recovery, through five steps from a cell extract of the stain. After the last step, the purified enzyme appeared to be homogeneous, as judged by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, analytical centrifugation, and double immunodiffusion in agarose. The relative molecular weight values for the native enzyme, estimated from the ultracentrifugal equilibrium and by high-performance liquid chromatog- raphy, were approximately 604,000 + 30,000 and 650,000, respectively, and the enzyme consisted of 15 to 16 subunits identical in molecular weight (41,000). The enzyme acted on aliphatic olefinic nitriles such as crotononitrile and acrylonitrile as the most suitable substrates. The apparent Km values for crotononitrile and acrylonitrile were 18.9 and 1.14 mM, respectively. The nitrilase also catalyzed the direct hydrolysis of saturated aliphatic nitriles, such as valeronitrile, 4-chlorobutyronitrile, and glutaronitrile, to the correspond- ing acids without the formation of amide intermediates. -

Chemical Name Federal P Code CAS Registry Number Acutely

Acutely / Extremely Hazardous Waste List Federal P CAS Registry Acutely / Extremely Chemical Name Code Number Hazardous 4,7-Methano-1H-indene, 1,4,5,6,7,8,8-heptachloro-3a,4,7,7a-tetrahydro- P059 76-44-8 Acutely Hazardous 6,9-Methano-2,4,3-benzodioxathiepin, 6,7,8,9,10,10- hexachloro-1,5,5a,6,9,9a-hexahydro-, 3-oxide P050 115-29-7 Acutely Hazardous Methanimidamide, N,N-dimethyl-N'-[2-methyl-4-[[(methylamino)carbonyl]oxy]phenyl]- P197 17702-57-7 Acutely Hazardous 1-(o-Chlorophenyl)thiourea P026 5344-82-1 Acutely Hazardous 1-(o-Chlorophenyl)thiourea 5344-82-1 Extremely Hazardous 1,1,1-Trichloro-2, -bis(p-methoxyphenyl)ethane Extremely Hazardous 1,1a,2,2,3,3a,4,5,5,5a,5b,6-Dodecachlorooctahydro-1,3,4-metheno-1H-cyclobuta (cd) pentalene, Dechlorane Extremely Hazardous 1,1a,3,3a,4,5,5,5a,5b,6-Decachloro--octahydro-1,2,4-metheno-2H-cyclobuta (cd) pentalen-2- one, chlorecone Extremely Hazardous 1,1-Dimethylhydrazine 57-14-7 Extremely Hazardous 1,2,3,4,10,10-Hexachloro-6,7-epoxy-1,4,4,4a,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydro-1,4-endo-endo-5,8- dimethanonaph-thalene Extremely Hazardous 1,2,3-Propanetriol, trinitrate P081 55-63-0 Acutely Hazardous 1,2,3-Propanetriol, trinitrate 55-63-0 Extremely Hazardous 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,8-Octachloro-4,7-methano-3a,4,7,7a-tetra- hydro- indane Extremely Hazardous 1,2-Benzenediol, 4-[1-hydroxy-2-(methylamino)ethyl]- 51-43-4 Extremely Hazardous 1,2-Benzenediol, 4-[1-hydroxy-2-(methylamino)ethyl]-, P042 51-43-4 Acutely Hazardous 1,2-Dibromo-3-chloropropane 96-12-8 Extremely Hazardous 1,2-Propylenimine P067 75-55-8 Acutely Hazardous 1,2-Propylenimine 75-55-8 Extremely Hazardous 1,3,4,5,6,7,8,8-Octachloro-1,3,3a,4,7,7a-hexahydro-4,7-methanoisobenzofuran Extremely Hazardous 1,3-Dithiolane-2-carboxaldehyde, 2,4-dimethyl-, O- [(methylamino)-carbonyl]oxime 26419-73-8 Extremely Hazardous 1,3-Dithiolane-2-carboxaldehyde, 2,4-dimethyl-, O- [(methylamino)-carbonyl]oxime. -

BUTADIENE AS a CHEMICAL RAW MATERIAL (September 1998)

Abstract Process Economics Program Report 35D BUTADIENE AS A CHEMICAL RAW MATERIAL (September 1998) The dominant technology for producing butadiene (BD) is the cracking of naphtha to pro- duce ethylene. BD is obtained as a coproduct. As the growth of ethylene production outpaced the growth of BD demand, an oversupply of BD has been created. This situation provides the incen- tive for developing technologies with BD as the starting material. The objective of this report is to evaluate the economics of BD-based routes and to compare the economics with those of cur- rently commercial technologies. In addition, this report addresses commercial aspects of the butadiene industry such as supply/demand, BD surplus, price projections, pricing history, and BD value in nonchemical applications. We present process economics for two technologies: • Cyclodimerization of BD leading to ethylbenzene (DSM-Chiyoda) • Hydrocyanation of BD leading to caprolactam (BASF). Furthermore, we present updated economics for technologies evaluated earlier by PEP: • Cyclodimerization of BD leading to styrene (Dow) • Carboalkoxylation of BD leading to caprolactam and to adipic acid • Hydrocyanation of BD leading to hexamethylenediamine. We also present a comparison of the DSM-Chiyoda and Dow technologies for producing sty- rene. The Dow technology produces styrene directly and is limited in terms of capacity by the BD available from a world-scale naphtha cracker. The 250 million lb/yr (113,000 t/yr) capacity se- lected for the Dow technology requires the BD output of two world-scale naphtha crackers. The DSM-Chiyoda technology produces ethylbenzene. In our evaluations, we assumed a scheme whereby ethylbenzene from a 266 million lb/yr (121,000 t/yr) DSM-Chiyoda unit is combined with 798 million lb/yr (362,000 t/yr) of ethylbenzene produced by conventional alkylation of benzene with ethylene. -

Acrylonitrile

Acrylonitrile 107-13-1 Hazard Summary Exposure to acrylonitrile is primarily occupational: it is used in the manufacture of acrylic acid and modacrylic fibers. Acute (short-term) exposure of workers to acrylonitrile has been observed to cause mucous membrane irritation, headaches, dizziness, and nausea. No information is available on the reproductive or developmental effects of acrylonitrile in humans. Based on limited evidence in humans and evidence in rats, EPA has classified acrylonitrile as a probable human carcinogen (Group B1). Please Note: The main sources of information for this fact sheet are EPA's Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) (4), which contains information on inhalation chronic toxicity of acrylonitrile and the RfC and the carcinogenic effects of acrylonitrile including the unit cancer risk for inhalation exposure, EPA's Health Effects Assessment for Acrylonitrile (6), and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry's (ATSDR's) Toxicological Profile for Acrylonitrile (1). Uses Acrylonitrile is primarily used in the manufacture of acrylic and modacrylic fibers. It is also used as a raw material in the manufacture of plastics (acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene and styrene-acrylonitrile resins), adiponitrile, acrylamide, and nitrile rubbers and barrier resins. (1,6) Sources and Potential Exposure Human exposure to acrylonitrile appears to be primarily occupational, via inhalation. (1) Acrylonitrile may be released to the ambient air during its manufacture and use. (1) Assessing Personal Exposure Acrylonitrile -

Itll Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory Iii:~ UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA APPLIED SCIENCE

LBL-24543 C'_~ ITll Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory iii:~ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA APPLIED SCIENCE -. ~ ., .. I DIVISION. •-, l:: '-' 1:: v L _ LAWRENCE EJr.:ov~L''"V_, .nc: c' LABORATORY APR 1 9 1988 LIBRARY AND The Use of Basic Polymer Sorbents DOCUMENTS SECTION for the Recovery of Acetic Acid from Dilute Aqueous Solution A.A. Garcia and C.J. King January 1988 '· . J I • .I APPLIED SCIENCE DIVISION Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC03-76SF00098 DISCLAIMER This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. While this document is believed to contain correct information, neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor the Regents of the University of California, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by its trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or the Regents of the University of Califomia. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof or the Regents of the University of California. LBL-24543 The Use of Basic Polymer Sorbents For The Recovery of Acetic Acid From Dilute Aqueous Solution Antonio Agustin Garcia and C. -

6-Aminocapronitrile As an Alternative Monomer for the Nylon 6 Synthesis

6-aminocapronitrile as an alternative monomer for the nylon 6 synthesis Citation for published version (APA): Dijk, van, A. J. M. (2006). 6-aminocapronitrile as an alternative monomer for the nylon 6 synthesis. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. https://doi.org/10.6100/IR608791 DOI: 10.6100/IR608791 Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2006 Document Version: Publisher’s PDF, also known as Version of Record (includes final page, issue and volume numbers) Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal.