Keep Smiling Through: Black Londoners on the Home Front

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Decolonising Knowledge

DECOLONISING KNOWLEDGE Expand the Black Experience in Britain’s heritage “Drawing on his personal web site Chronicleworld.org and digital and print collection, the author challenges the nation’s information guardians to “detoxify” their knowledge portals” Thomas L Blair Commentaries on the Chronicleworld.org Users value the Thomas L Blair digital collection for its support of “below the radar” unreported communities. Here is what they have to say: Social scientists and researchers at professional associations, such as SOSIG and the UK Intute Science, Engineering and Technology, applaud the Chronicleworld.org web site’s “essays, articles and information about the black urban experience that invite interaction”. Black History Month archived Bernie Grant, Militant Parliamentarian (1944-2000) from the Chronicleworld.org Online journalists at the New York Times on the Web nominate THE CHRONICLE: www.chronicleworld.org as “A biting, well-written zine about black life in Britain” and a useful reference in the Arts, Music and Popular Culture, Technology and Knowledge Networks. Enquirers to UK Directory at ukdirectory.co.uk value the Chronicleworld.org under the headings Race Relations Organisations promoting racial equality, anti- racism and multiculturalism. Library”Govt & Society”Policies & Issues”Race Relations The 100 Great Black Britons www.100greatblackbritons.com cites “Chronicle World - Changing Black Britain as a major resource Magazine addressing the concerns of Black Britons includes a newsgroup and articles on topical events as well as careers, business and the arts. www.chronicleworld.org” Editors at the British TV Channel 4 - Black and Asian History Map call the www.chronicleworld.org “a comprehensive site full of information on the black British presence plus news, current affairs and a rich archive of material”. -

Cole Albert Porter (June 9, 1891 October 15, 1964) Was An

Cole Albert Porter (June 9, 1891 October 15, 1964) was an American composer and songwriter. Born to a wealthy family in Indiana, he defied the wishes of his dom ineering grandfather and took up music as a profession. Classically trained, he was drawn towards musical theatre. After a slow start, he began to achieve succe ss in the 1920s, and by the 1930s he was one of the major songwriters for the Br oadway musical stage. Unlike many successful Broadway composers, Porter wrote th e lyrics as well as the music for his songs. After a serious horseback riding accident in 1937, Porter was left disabled and in constant pain, but he continued to work. His shows of the early 1940s did not contain the lasting hits of his best work of the 1920s and 30s, but in 1948 he made a triumphant comeback with his most successful musical, Kiss Me, Kate. It w on the first Tony Award for Best Musical. Porter's other musicals include Fifty Million Frenchmen, DuBarry Was a Lady, Any thing Goes, Can-Can and Silk Stockings. His numerous hit songs include "Night an d Day","Begin the Beguine", "I Get a Kick Out of You", "Well, Did You Evah!", "I 've Got You Under My Skin", "My Heart Belongs to Daddy" and "You're the Top". He also composed scores for films from the 1930s to the 1950s, including Born to D ance (1936), which featured the song "You'd Be So Easy to Love", Rosalie (1937), which featured "In the Still of the Night"; High Society (1956), which included "True Love"; and Les Girls (1957). -

Issue 205 Autumn 2020

CAMBERWELLCAMBERWELL QUARTERLYQUARTERLY The magazine of the Camberwell Society The magazine of The Camberwell Society NoNo 202 205 Winter Autumn 2019 2020 £1.50 £1.50 (free (free to to members)members) www.camberwellsociety.org.ukwww.camberwellsociety.org.uk Green light for new station entrance – p4 Camberwell’s black music hall stars – p5 Is Covid making GPs remote and anonymous? – p7 Burgess Business Park Development stopped by resi- dents – p9 St Giles’ Churchyard and its haunted passage – p12 New walk: through Camberwell’s black history – p6 More a gent than an agent Colin Lowman obituary – p15 Remembering Conrad and Marilyn Dehn – p14 Camberwell’s food bank – p18 Gazette LOCAL SOCIETIES, VENUES AND EVENTS Contents We recommend checking details Report from the Chair ......................3 Open Gardens ...................................3 Denmark Hill Station – green Brunswick Park Neighbourhood Peckham Society light for second entrance ..................4 Tenants and Residents Association Peter Frost Steppin’ out with black music Patricia Ladly 020 8613 6757 hall stars ...........................................5 020 7703 7491 www.peckhamsociety.org.uk [email protected] Black history walk ...........................6 Ruskin Park, Friends of COVID is making GPs remote Brixton Society Doug Gillies and anonymous .................................. 7 www.brixtonsociety.org.uk 020 7703 5018 Victory for Burgess Park Burgess Park, Friends of SE5 Forum campaigners ......................................9 www.friendsofburgesspark.org.uk -

Full List of Publications for Sale

Publications for Sale At Southwark Local History Library and Archive The Neighbourhood Histories series: Illustrated A5-size histories of the communities within the London Borough of Southwark: The Story of the Borough by Mary Boast £1.95 Covers Borough High Street, and the parishes of St George the Martyr and Holy Trinity The Story of Walworth by Mary Boast £4.00 Covers the parish of St Mary Newington, the Elephant and Castle and the Old Kent Road The Story of Rotherhithe by Stephen Humphrey £3.50 Covers the parish of St Mary Rotherhithe, Surrey Docks, Southwark Park The Story of Camberwell by Mary Boast £3.50 Covers the Parish of St Giles Camberwell, Burgess Park, Denmark Hill The Story of Dulwich by Mary Boast £2.00 Covers the old village and Dulwich Picture Gallery The Story of Peckham and Nunhead by John Beasley £4.00 Covers Rye Lane, houses, Peckham Health Centre, World War I and II and people @swkheritage Southwark Local History Library and Archive 211 Borough High Street, London SE1 1JA southwark.gov.uk/heritage Tel: 020 7525 0232 [email protected] Southwark: an Illustrated History by Leonard Reilly £6.95 An overview of Southwark’s History, lavishly illustrated with over 100 views, many in colour Southwark at War, ed. By Rib Davis and Pam Schweitzer £2.50 A collection of reminiscences from the Second World War which tells the Story of ordinary lives during this traumatic period. Below Southwark by Carrie Cowan £4.95 A 46-page booklet showing the story of Southwark, revealed by excavations over the last thirty years. -

Journal of British Studies

Journal of British Studies 'The show is not about race': Custom, Screen Culture, and The Black and White Minstrel Show --Manuscript Draft-- Manuscript Number: 4811R2 Full Title: 'The show is not about race': Custom, Screen Culture, and The Black and White Minstrel Show Article Type: Original Manuscript Corresponding Author: Christine Grandy, Ph.D. University of Lincoln Lincoln, Lincolnshire UNITED KINGDOM Corresponding Author Secondary Information: Corresponding Author's Institution: University of Lincoln Corresponding Author's Secondary Institution: First Author: Christine Grandy, Ph.D. First Author Secondary Information: Order of Authors: Christine Grandy, Ph.D. Order of Authors Secondary Information: Abstract: In 1967, when the BBC was faced with a petition by the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD) requesting an end to the televised variety programme, The Black and White Minstrel Show (1958-1978), producers at the BBC, the press, and audience members collectively argued that the historic presence of minstrelsy in Britain rendered the practice of blacking up harmless. This article uses Critical Race Theory as a useful framework for unpacking defences that hinged both on the colour-blindness of white British audiences, and the simultaneous existence of wider customs of blacking up within British television and film. I examine a range of 'screen culture' from the 1920s to the 1970s, including feature films, home movies, newsreels, and television, that provide evidence of the existence of blackface as a type of racialised custom in British entertainment throughout this period. Efforts by organisations such as CARD, black-press publications like Flamingo, and audiences of colour, to name blacking up and minstrelsy as racist in the late 1960s were met by fierce resistance from majority white audiences and producers, who denied their authority to do so. -

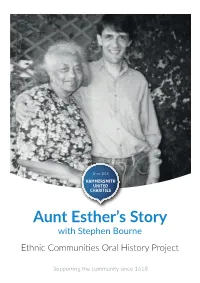

Aunt Esther's Story

Since 1618 HAMMERSMITH UNITED CHARITIES Aunt Esther’s Story with Stephen Bourne Ethnic Communities Oral History Project Supporting the community since 1618 Aunt Esther’s Story Compiled by Stephen Bourne & Sav Kyriacou © Ethnic Communities Oral History Project 1991 1 INTRODUCTION by Stephen Bourne Black women have been living and working in Britain since at least the early 16th century. The court of King James IV of Scotland included two African maidservants to the Queen. From the seventeenth century black women found employment as domestic servants, seamstresses, laundry maids, children’s nurses, cooks and street and fairground performers. However, many were forced to become prostitutes. It is a little known fact that four hundred years ago, in 1595, a tall, statuesque African called Luce Morgan, also known as Lucy Negro, ran a brothel in Clerkenwell. A beautiful and famous courtesan, some historians believe that Shakespeare fell in love with her, and they have identified her as his Dark Lady of the Sonnets. Luce Morgan may have inspired Shakespeare, but in those days women had very little access to education, and left no written records. Poet Phillis Wheatley became the first black woman to have her writing published in Britain. Bought in a slave-market in 1761 when she was just seven- years-old, Wheatley grew up in America and came to London in 1773. Under the patronage of the Countess of Huntingdon, Wheatley’s poems were published here to great acclaim, and subsequently she was befriended and entertained by members of the English aristocracy. She died in 1784. Another slave, Mary Prince, was born in Bermuda in 1788 but, unlike Wheatley, she suffered barbaric treatment from her owners. -

Rights Catalogue Spring 2016 Jacaranda Books Art Music Ltd Is a Fresh and Exciting New Independent Publishing House Based in London

Rights catalogue Spring 2016 Jacaranda Books Art Music Ltd is a fresh and exciting new independent publishing house based in London. We publish adult fiction and non- fiction, including illustrated books, across linguistic, racial, gender and cultural boundaries – books in many ways as cosmopolitan as our city. Through our publishing, we directly address the ongoing lack of diversity in the industry today, and seek to enrich the landscape from boardroom to bookshelf. We aim to bring authors and books that represent the cultural, heritage and ethnic variety that can be found in London, with a particular interest in works related to Africa, the Caribbean, and African America. At the heart of our publishing strategy is one core element: a love of outstanding, thought-provoking work. We believe that a wealth of unheard, under-represented voices exist globally and are ready to be discovered. It is our mission to create the space for those voices to be seen and heard by new readers. Valerie Brandes Founder and Publisher Jacaranda 2 RADIO SUNRISE ANIETIE ISONG JANUARY 2017 Literary fiction, Satire Binding: B-format paperback Extent: 160 pp Price: £7.99 Rights: World ‘Never cover an assignment without collecting a brown ANIETIE ISONG started his career as a journalist envelope,’ Boniface had said. ‘It is a real life saver for all with Radio Nigeria, in Lagos. His short stories have journalists in this country.’ been published in journals and broadcast on the BBC and Radio Nigeria. He won several awards, Ifiok, a young journalist working for the government including the Commonwealth Short Story Award in radio station in Lagos, aspires to always do the right 2000 and the Remember Oluwale Writing Prize in thing but the odds seem to be stacked against him. -

Race, Culture & Identity (DSS 6 RCI)

Module Guide ‘Race’, Culture and Identity Division of Social Sciences Level 6 Template version: 8 Table of Contents 1. Module Details 2. Short Description 3. Aims of the Module 4. Learning Outcomes 4.1 Knowledge and Understanding 4.2 Intellectual Skills 5. Assessment of the Module 6. Feedback 7. Student Evaluation 8. Introduction to Studying the Module 8.1 Overview of the Main Content 8.2 Overview of Types of Classes 8.3 Importance of Student Self-Managed Learning Time 8.4 Employability 9. The Programme of Teaching, Learning and Assessment 10. Learning Resources Overview of lecture programme WEEK TOPIC 1 Introductory Seminar and the Question of Identity 2 Theoretical Understanding of ‘Race’ and Racism 3 ‘Race ‘ and Whiteness 4 Historical Context of ‘Race’ and Racism 5 Student self-directed study week 6 ‘Race’ and the Media 7 Guest Lecture 8 Youth Culture and Identity 9 Representation of ‘Race’ and Sexuality in Film 10 Race’, Women and Feminism 11 Race Relations Legislation and the Racialisation of Politics 12 Overview of the Module Template version: 8 2 1. MODULE DETAILS Module Title: Race, Culture and Identity Module Level: 6 Module Reference Number: DSS_6_RCI Credit Value: 20 Student Study Hours: 200 Contact Hours: 45 Private Study Hours: 155 Pre-requisite Learning (If applicable): Level 5 Modules Co-requisite Modules (If applicable): None Course(s): BSc (Hons) Sociology 1 Module Coordinator: Dr Shaminder Takhar MC Contact Details (Tel, Email, Room) 020 7815 5748; [email protected], BR241 Teaching Team & Contact Details (If applicable): Subject Area: Sociology Summary of Assessment Method: 1 essay 3,000 words [100% of assessment] The Library Information Officer for DSS Rebecca Fong [email protected] External Examiner appointed for module: Dr Gary Hazeldine School of Social Sciences Birmingham City University 2. -

Carlos Trower, the African Blondin 7 by Ron Howard the Real Black Heathcliffs – and Heathers 11 by Audrey Dewjee

BASA (Black & Asian Studies Association) NEWSLETTER Elizabeth Welch honoured (p. 15) # 62 March 2012 Contents: March 2012 Features Una Marson 3 by Imaobong Umoren Carlos Trower, the African Blondin 7 by Ron Howard The Real Black Heathcliffs – and Heathers 11 by Audrey Dewjee Regulars News 14 Magazine round-up 20 Parish and other records 22 Historic document: A Rescued Slave 23 Book reviews: 24 General History Education Arts Local History Biography Historic figure: Bert Williams 33 by Jeffery Green Editor’s Note Much to my surprise, the item which caused the most comment in the last double issue of the Newsletter was not one of the articles but Jeffrey Green’s review of Marika Sherwood’s book about Henry Sylvester Williams. It was not laudatory – and not only did this prompt a comment on the BASA jiscmail, people actually came up to me at events to ask about it. I did not expect this. BASA is an association set up to study Black and Asian history in Britain. It is not, and should never be, a cosy little self-congratulatory club, smugly puffing its members’ activities. Marika herself wrote a critical review of a book by chairman George Watley in a previous issue. She has asked for, and got, a published rejoinder to Jeffrey’s review (p. 32). On the subject of criticism, I would like to see contributions that are, even occasionally, critical of their subjects or aspects of their lives. I understand that within a short article it is difficult to discuss and balance factors at length but a hagiographic approach is both tiresome and patronising. -

Black British Film and Television

source guides black british film and television National Library black british film and television 16 + Source Guide contents THE CONTENTS OF THIS PDF CAN BE VIEWED QUICKLY BY USING THE BOOKMARK FACILITY INFORMATION GUIDE STATEMENT . .i BFI NATIONAL LIBRARY . .ii ACCESSING RESEARCH MATERIALS . .iii APPROACHES TO RESEARCH, by Samantha Bakhurst . .iv GENERAL REFERENCES . .1 FILM REFERENCES . .2 TELEVISION REFERENCES . .6 WOMEN’S PERSPCTIVES . .11 PERSONALITIES NORMAN BEATON . .12 LENNY HENRY . .13 CASE STUDY: PRESSURE . .15 DVD AVAILABILIY . .16 Compiled by: Nicola Clarke Andrea King Matt Ker Design/Layout: Ian O’Sullivan Project Manager: David Sharp © 2000 BFI National Library, 21 Stephen Street, London W1T 1LN 16+ MEDIA STUDIES INFORMATION GUIDE STATEMENT “Candidates should note that examiners have copies of this guide and will not give credit for mere reproduction of the information it contains. Candidates are reminded that all research sources must be credited”. BFI National Library i BFI National Library All the materials referred to in this guide are available for consultation at the BFI National Library. If you wish to visit the reading room of the library and do not already hold membership, you will need to take out a one-day, five-day or annual pass. Full details of access to the library and charges can be found at: www.bfi.org.uk/filmtvinfo/library BFI National Library Reading Room Opening Hours: Monday 10.30am - 5.30pm Tuesday 10.30am - 8.00pm Wednesday 1.00pm - 8.00pm Thursday 10.30am - 8.00pm Friday 10.30am - 5.30pm If you are visiting the library from a distance or are planning to visit as a group, it is advisable to contact the Reading Room librarian in advance (tel. -

To View Or Download the Exhibition Checklist Please Click Here

GATHER OUT OF STAR-DUST The Harlem Renaissance & The Beinecke Library JANUARY 13 – APRIL 17, 2017 AT YALE UNIVERSITY Melissa Barton, Curator of Drama and Prose, Yale Collection of American Literature This exhibition was organized with the assistance of Olivia Hillmer Additional support provided by Phoenix Alexander GRD ’18 and Lucy Caplan GRD ’18 Additional commentary by Professor Robert B. Stepto THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: 6. Marcus Garvey. An Appeal to the Soul of White America. New York: A CHRONOLOGY Universal Negro Improvement Association [?], 1923. 7. Window card for national tour of The Emperor Jones, 1921. A timeline of African American culture from 1910-1940, while 8. Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake. “I’m Just Wild About Harry,” in far from comprehensive, o≠ers a sense of the abundance, vari- Shu≠le Along. New York: M. Witmark and Sons, 1921. ety, and texture of documentation for this period available in the 9. Jessie Fauset. Letter to Langston Hughes, January 16, 1921. James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection. The chronologi- Langston Hughes Papers. cal arrangement gives rise to interesting juxtapositions, such as 10. Claude McKay. Harlem Shadows. New York: Harcourt, Brace, and the appearance in the same year—1917—of Ridgley Torrence’s Company, 1922. “Negro plays” on Broadway and the N.A.A.C.P.’s Negro Silent 11. James Weldon Johnson. “A Real Poet.” New York Age, May 20, 1922. Protest Parade, or the emergence of Jean Toomer with Cane in 12. Claude McKay’s membership card for the Russian Communist the same year—1923—as the Charleston. Well-known events Party, March 1923. -

APRIL 2006 - the NEWSLETTER of the NOËL COWARD SOCIETY 1 to 12 Jun - New Era Players Theatre, Newbury, Berkshire Sat

Relative Values (continued...) Relative Values 6 to 11 Feb - Newton ADS, Powys Theatre, Newtown, Powys 31 Mar - May 6 - The Masquers a FREE TO 10 to 13 May - 8pm, Ruislip Dramatic Society community theatre in Point MEMBERS OF at the Compass Theatre, Glebe Avenue, Ickenham near Richmond, CA, on the East shore THE SOCIETY Ruislip. For further details goto: www.ruislipdramatic.org of the San Francisco Bay at 105, Price £3 ($5) Still Life Park Place, Point Richmond. 22 to 29 Jul - New Venture Theatre, Brighton, E. Sussex Directed by Robert Taylor. Call CHAT This Happy Breed 510-232-4031 to reserve.Fri. and homeAPRIL 2006 - THE NEWSLETTER OF THE NOËL COWARD SOCIETY 1 to 12 Jun - New Era Players Theatre, Newbury, Berkshire Sat. at 8 p.m.through May 6. Design For Living Tickets are $15. 232-4031. 25 to 29 Apr Tower Theatre's production at the Bridewell www.masquers.org MEMBERS MEET DAME JUDI! Theatre, Bride Lane, London EC4 17 to 18 Mar - University Of Central Lancashire Students' In the Rest of the World... sparkling evening awaits Noël Coward Society Members and their guests on Tuesday 6th June Union Drama Society, The Charter Theatre, Preston, 2006 for the new production of Hay Fever at the Theatre Royal Haymarket. We have 60 tickets Lancashire. Director: Christopher Fitzsimmons. Tickets £10 Australia for this star studded evening that includes a good theatre seat and a meeting with Dame Judi conc. £7 BO: 01772 258858 Private Lives A who has agreed to join us for drinks after the performance. This will be a very special occasion Queensland Theatre Co & State Theatre Co of South for the Society with one of the legends of the British theatre.