Illuminating Shanghai: Light, Heritage, Power1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Letter from China 21 July 2014

A letter from China 21 July 2014 Interesting things to do with skyscrapers Much work has been done on Shanghai’s architecture during the 1920s & 30s. I refer interested readers to the beautifully illustrated work of Tess Johnston. Less has been written on the boom in skyscraper building that we have seen over the past 25 years. The vast creation of private wealth here, combined with a government willing and able to make grand architectural statements, has led to a sustained exuberance in the design of tall buildings. It all started here. This unlovely building, the Shanghai Union Friendship Tower, was the first skyscraper of the modern era, completed in 1985, just off the Bund. (The more imaginative building in the background with the leaf crown is the Bund Centre, built in 2002.) Before then, Lazlo Hudec’s Park Hotel, alongside Shanghai’s race Shanghai Union Friendship Tower track, had held the title of the city’s tallest building since its construction in 1934. It was from this vantage point that your correspondent watched President Reagan’s motorcade when he visited Shanghai in April 1984. That’s the Park Hotel to the left, its 22 floors now overborne by the 47-floor Radisson New World (2005), with its “the Martians have landed” motif. This is a late example of the revolving-restaurant fad. In the West, revolving restaurants were a thing of the 1960s and 1970s. But at that time China was busy with its own Cultural Park Hotel/Radisson New World Revolution. So the 1980s was China’s first chance to build something so cool. -

Trade Finance Program Confirming Banks List As of 31 December 2015

Trade Finance Program Confirming Banks List As of 31 December 2015 AFGHANISTAN Bank Alfalah Limited (Afghanistan Branch) 410 Chahri-e-Sadarat Shar-e-Nou, Kabul, Afghanistan National Bank of Pakistan (Jalalabad Branch) Bank Street Near Haji Qadeer House Nahya Awal, Jalalabad, Afghanistan National Bank of Pakistan (Kabul Branch) House No. 2, Street No. 10 Wazir Akbar Khan, Kabul, Afghanistan ALGERIA HSBC Bank Middle East Limited, Algeria 10 Eme Etage El-Mohammadia 16212, Alger, Algeria ANGOLA Banco Millennium Angola SA Rua Rainha Ginga 83, Luanda, Angola ARGENTINA Banco Patagonia S.A. Av. De Mayo 701 24th floor C1084AAC, Buenos Aires, Argentina Banco Rio de la Plata S.A. Bartolome Mitre 480-8th Floor C1306AAH, Buenos Aires, Argentina AUSTRALIA Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited Level 20, 100 Queen Street, Melbourne, VIC 3000, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Adelaide Branch) Level 20, 11 Waymouth Street, Adelaide, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Adelaide Branch - Trade and Supply Chain) Level 20, 11 Waymouth Street, Adelaide, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Brisbane Branch) Level 18, 111 Eagle Street, Brisbane QLD 4000, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Brisbane Branch - Trade and Supply Chain) Level 18, 111 Eagle Street, Brisbane QLD 4000, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Perth Branch) Level 6, 77 St Georges Terrace, Perth, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Perth Branch -

New Development Bank 2020 Renminbi Bond (Series 2) (Bond Connect) Prospectus

New Development Bank 2020 Renminbi Bond (Series 2) (Bond Connect) Prospectus Issuer: New Development Bank Address: 32-36 Floors, 333 Lujiazui Ring Road, Pudong New District, Shanghai, China Lead Underwriter and Bookrunner: Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Limited Joint Underwriter: Bank of China Limited Joint Underwriter: Agricultural Bank of China Limited Joint Underwriter: China Construction Bank Limited June 2020 IMPORTANT NOTICE AND DECLARATION The New Development Bank (“NDB”, the “Issuer” or the “Bank”) may, from time to time during the period of two years commencing on the date of issuance by the National Association of Financial Market Institutional Investors (“NAFMII”) of the registration notice with respect to the Programme (dated 9 January 2019, with the serial number of NAFMII Zhong Shi Xie Zhu [2019]RB1), issue Renminbi Bonds in an aggregate amount of RMB10,000,000,000 in the Interbank Market. The Issuer issued the New Development Bank 2019 Renminbi Bond (Series 1) (Bond Connect) in the amount of RMB3,000,000,000 on 22 February 2019 and the New Development Bank 2020 Renminbi Bond (Series 1) (Coronavirus Combating Bond) (Bond Connect) in the amount of RMB5,000,000,000 on 1 April 2020. The Issuer hereby intends to issue the New Development Bank 2020 Renminbi Bond (Series 2) (Bond Connect) in the amount of RMB2,000,000,000. The Bonds will be publicly offered in the Interbank Market. Investors should carefully read this Prospectus and the other relevant Disclosure Documents (as defined in Section 1 (Definitions)), and carry out their own independent investment analysis. The registration of the Programme with NAFMII does not indicate that it has made any assessment of the investment value of the Bonds, nor does it indicate that it has made any judgments with respect to risks of investing in the Bonds. -

The Emergence of Shanghai's Decentralised Office Market

The Emergence of Shanghai’s Decentralised Office Market Advance Executive Summary • Decentralised Grade A space is the next • Buildings that are well integrated into a cluster step in the evolution of Shanghai’s office of diverse property types will be the most market, following the path taken by mature successful in the decentralised office market by markets around the world. providing an attractive environment for tenants. • Shanghai is the first city in mainland China to The Next Step in Shanghai’s Office develop a clearly defined Decentralised Grade Evolution A market. The emergence of a decentralised Grade A office • An increasing number of new buildings, which market is the natural next step in the evolution are located just outside the CBD, are being built of Shanghai’s office market, following the path to high-quality specifications and are quickly taken by mature markets around the world. becoming conveniently accessible. Over the next two years, decentralised Grade A office space will be readily available in the • Owing to the rapidly growing metro rail system, Shanghai market, providing tenants with lower- better integration with the city centre means that cost options just a short distance from the CBD. decentralised tenants can reap the benefits of These projects represent the first generation lower occupancy costs while maintaining solid of Grade A quality space outside the CBD that employee retention. offer high-quality specification suitable for large • The CBD will have strong competition in the multinational occupiers. Until recently, Grade next few years as the booming decentralised A quality supply could not be found outside Grade A office market will offer highly the CBD. -

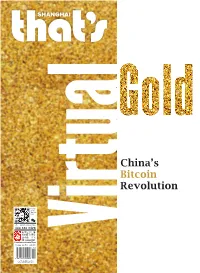

Virtualchina's Bitcoin Revolution

China’s Bitcoin Revolution Virtual 城市漫步上海 英文版 10 月份 国内统一刊号: CN 11-5233/GO China Intercontinental Press OCTOBER 2016 that’s Shanghai 《城市漫步》上海版 英文月刊 主管单位 : 中华人民共和国国务院新闻办公室 Supervised by the State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China 主办单位 : 五洲传播出版社 地址 : 中国北京 北京西城月坛北街 26 号恒华国际商务中心南楼 11 层文化交流中心 邮编 100045 Published by China Intercontinental Press Address: 11th Floor South Building, HengHua linternational Business Center, 26 Yuetan North Street, Xicheng District, Beijing 100045, PRC http://www.cicc.org.cn 总编辑 Editor in Chief of China Intercontinental Press: 慈爱民 Ci aimin 期刊部负责人 Supervisor of Magazine Department: 邓锦辉 Deng Jinhui 主编 Executive Editor: 袁保安 Yuan Baoan 编辑 Editor: 朱莉莉 Zhu Lili 发行 / 市场 Circulation/Marketing: 黄静 Huang Jing, 李若琳 Li Ruolin 广告 Advertising: 林煜宸 Lin Yuchen Chief Editor Dominic Ngai Section Editors Andrew Chin, Betty Richardson Senior Editor Tongfei Zhang Events Editor Zoey Zha Production Manager Ivy Zhang Designer Joan Dai, Aries Ji Contributors Mario Grey, Mia Li, Ian Walker, Alyssa Wieting, Bailey Hu, Dr. Richeller Yling, Josh Peachey, Jonty Dixon, Lauren Hogan, Noelle Mateer Copy Editor Susie Gordon HK FOCUS MEDIA Shanghai (Head office) 上海和舟广告有限公司 上海市蒙自路 169 号智造局 2 号楼 305-306 室 邮政编码 : 200023 Room 305-306, Building 2, No.169 Mengzi Lu, Shanghai 200023 电话 : 021-8023 2199 传真 : 021-8023 2190 Guangzhou 上海和舟广告有限公司广州分公司 广州市越秀区麓苑路 42 号大院 2 号楼 610 室 邮政编码 : 510095 Room 610, No. 2 Building, Area 42, Luyuan Lu, Yuexiu District, Guangzhou 510095 电话 : 020-8358 6125, 传真 : 020-8357 3859-800 Shenzhen 广告代理 : 上海和舟广告有限公司广州分公司 -

Marketscore the Key to Investing in China China Q1 2014

MARKETSCORE The Key to Investing in China CHINA Q1 2014 GLOBAL RESEARCH & OFFICES CONSULTING Contents Introduction 1 Methodology 2 Office Investment 4 Market Summary 4 City Highlights 5 Beijing: Market Outlier 5 Shanghai: Low Risk, Stable Return 7 Wuhan: Stay Low, Aim High 10 Chengdu: Opportunities and Challenges 13 Local Rivals: Chengdu vs. Chongqing 14 Tianjin: Elusive Demand 16 Contacts 18 MARKETSCORE REPORT OFFICES Introduction China has emerged as a major investment target for global real estate investors thanks to its rapid economic growth and growing strategic importance as the world’s second largest economy. According to ANREV’s investor intention survey 2013, Greater China is the most preferred location in the Asia Pacific for real estate investment, with as many as 59% of the respondents naming it the top destination. Preferred country and sector in Asia Pacific for real estate investment 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Greater China Australia Emerging SEA Singapore Japan India South Korea Malaysia InvestorsInvestor F u n d o f F u FnUNDd Ma nOFag eFrUNDs MFuanagersnd Manag e r s FUND Managers Source: ANREV investor intention survey 2013 While there is no shortage of interest in investing in China, investors, especially foreign ones, face multiple challenges as they formulate their investment strategy and execute their acquisitions. China has over 90 cities with an urban population of over one million, far more than the total in the US and Europe combined. After over thirty years of rapid economic growth, the country is highly diversified, and regional economic growth and social development is seriously imbalanced. -

ADB's Trade Finance Program Confirming Banks List

Trade Finance Program Confirming Banks List As of 13 February 2017 AFGHANISTAN Bank Alfalah Limited (Afghanistan Branch) 410 Chahri-e-Sadarat Shar-e-Nou, Kabul, Afghanistan National Bank of Pakistan (Jalalabad Branch) Bank Street Near Haji Qadeer House Nahya Awal, Jalalabad, Afghanistan National Bank of Pakistan (Kabul Branch) House No. 2, Street No. 10 Wazir Akbar Khan, Kabul, Afghanistan ALGERIA HSBC Bank Middle East Limited, Algeria 10 Eme Etage El-Mohammadia 16212, Alger, Algeria ANGOLA Banco Millennium Angola SA Rua Rainha Ginga 83, Luanda, Angola ARGENTINA Banco Patagonia S.A. Av. De Mayo 701 24th floor C1084AAC, Buenos Aires, Argentina Banco Rio de la Plata S.A. Bartolome Mitre 480-8th Floor C1306AAH, Buenos Aires, Argentina AUSTRALIA Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited Level 20, 100 Queen Street, Melbourne, VIC 3000, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Adelaide Branch) Level 20, 11 Waymouth Street, Adelaide, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Adelaide Branch - Trade and Supply Chain) Level 20, 11 Waymouth Street, Adelaide, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Brisbane Branch) Level 18, 111 Eagle Street, Brisbane QLD 4000, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Brisbane Branch - Trade and Supply Chain) Level 18, 111 Eagle Street, Brisbane QLD 4000, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Perth Branch) Level 6, 77 St Georges Terrace, Perth, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Perth Branch -

Hong Kong Covering Document – January 2016 CIFM China Emerging Power Fund

Hong Kong Covering Document – January 2016 CIFM China Emerging Power Fund Mainland-Hong Kong Mutual Recognition of Funds www.jpmorganam.com.hk Fund Manager: Main Distributor in Hong Kong: 0116 CIFM China Emerging Power Fund (the “Fund”) FIFTH ADDENDUM This Fifth Addendum forms an integral part of and should be read in conjunction with the Hong Kong Covering Document of the Fund dated January 2016, as amended from time to time (the “HKCD”). China International Fund Management Co., Ltd. (the “Fund Manager”) accepts full responsibility for the accuracy of the information contained in this Addendum, and confirms, having made all reasonable enquiries, that to the best of their knowledge and belief there are no other facts the omission of which would make any statement misleading. Capitalized terms used herein not otherwise defined have the meaning ascribed to those terms in the Fund’s HKCD. With effect from 31 March 2021, the HKCD shall be amended as follows: (i) The fourth paragraph of the section headed “Settlement” in page 16 of the HKCD is deleted in its entirety and replaced with the following: “Please note that payment of redemption proceeds may be deferred in the circumstances as set out in the sub-section headed “(VII) Suspension of Redemption or Deferral Payment of Redemption Monies” under the section headed “VII. Subscription, Redemption and Switching of Units”, as well as, the section headed “XVI. Side Pocket Mechanism” of the Prospectus. In these circumstances, the extended time frame for the payment of redemption proceeds shall -

Infrastructure Asset Management Review of Tall Residential Buildings Of

Journal of Built Environment, Technology and Engineering, Vol. 3 (September) 2017 ISSN 0128-1003 ASSET MANAGEMENT REVIEW OF TALL RESIDENTIAL BUILDINGS IN MAJOR CITIES: CHICAGO, HONG KONG AND SINGAPORE Raymond Cheng Email: [email protected] Reader, Industrial Doctorate (IndD) Programme, Asia e University, Kuala Lumpur, MALAYSIA Ivan Ng Email: [email protected] Executive Director, Russia Capital Investment Corporation Limited, HONG KONG ABSTRACT There is only one residential skyscraper within China’s top 100 tallest buildings in the crowded 24-million- population city of Shanghai, China (and eleven residential skyscrapers among the 134 tallest buildings, i.e. those taller than 150 metres), whereas there are comparatively a lot more skyscrapers used for residential purposes in equally densely populated cities like Hong Kong, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and, of course, Chicago and New York. This paper, hence, looked, from a historical perspective, how the development of tall buildings in Chicago, Hong Kong and Singapore have evolved to become what we see today. How does the tall building development history of a city help forge the people’s view in terms of living in skyscrapers? Would such help provide explanations and hints as to the future development of skyscrapers in the other cities like Shanghai? Keywords: Tall building, skyscraper, high-rise, development history Learning from the American experience The mythical story of the Tower of Babel tells us that how height, in itself, since the beginning of known history, means power to human beings. But before Elisha Otis revolutionized and refined the safety of the elevator by inventing the elevator brakes1 in 1852, both the Greek mathematician Archimedes of Syracuse and King Louis XV of France could only have envisioned their great ideas through primitive, man-powered, inefficient mechanical lifting devices back in their days. -

Citigroup Tower, 33 Hua Yuan Shi Qiao Road, Pudong, Shanghai

Citigroup Tower, 33 Hua Yuan Shi Qiao Road, Pudong, Shanghai View this office online at: https://www.newofficeasia.com/details/offices-citigroup-tower-hua-yuan-shi-qi ao-pudong-china This is your chance to aquire one of the most recognisable business addresses in the area. The state of the art offices are well equipped with all of the latest appliances needed to run a profitable business, no wonder so many multi- national companies have already located their headquarters here. The breathtaking views over Shanghai Bund and the Huangpu River are just icing on the cake. The professional services and facilities on offer include; manned reception with telephone answering service, administrative support and video conferencing facilities. Transport links Nearest tube: Lu Jia Zui Station Nearest railway station: Shanghai Railway Station Nearest road: Lu Jia Zui Station Nearest airport: Lu Jia Zui Station Key features 24 hour access Access to multiple centres nation-wide Access to multiple centres world-wide Administrative support AV equipment Car parking spaces Close to railway station Conference rooms Conference rooms High speed internet High-speed internet IT support available Meeting rooms Modern interiors Reception staff Security system Shower cubicles Telephone answering service Town centre location Unbranded offices Video conference facilities Location This business centre is in a great location in Lujiazui, highly regarded as the financial nerve centre of Shanghai. Right on the waterfront of the Huangpu River, it's just a 5 minute walk to Metro II Lujiazui Station, or a 45 minute drive to Shanghai Pudong International Airport. Your business could not be better placed to succeed. -

Global Projects

Global Projects 119_Cover.indd 2-3 5/3/16 2:59 PM National Projects 119_Guts.indd 1 5/3/16 4:45 PM Venetian Macao COTAI STRIP, MACAU, CHINA The Venetian Macao, designed by HKS, Inc. and Aedas, is a luxury hotel Valspar Global Projects resort and the world’s largest casino spanning 500,000 square feet. Recalling the Venetian Gothic architecture of the famed Palazzo For more than 200 years, Valspar has led the way in developing Ducale (Doge’s Palace) in its ornate and colonnaded entrance façade, the exterior of the immense complex features a unique curtain wall high-performance coatings for a wide-range of applications. that utilizes Valspar coatings to draw attention to design features. Today, our global team of technology experts—including chemists, In a winning combination, the Venetian Macao features a selection scientists, technical staff and sales consultants—works with of Valspar’s high-performing Fluropon® coating in Grey and White, architects, builders and fabricators to develop innovative solutions for and Fluropon Classic II in sparkling pearlescent Pearl Clear, Dark Silver extraordinary buildings. and Light Bronze. Fluropon coatings are widely recognized for their durability properties to create a lasting impression. Developed as a niche product over 50 years ago, it has shaped an industry, redefining its sense of the possibilities of color. Today it can be found on monumental buildings around the world—such as those pictured here. We combine this track record of innovation with a commitment to exceptional customer service, whether that means creating the perfect color, meeting your toughest deadlines or fixing a problem on a moment’s notice. -

Time for Thu Thiem the Largest Mixed-Use Inner City Development in Southeast Asia Key Takeaways from This Report

Vietnam | November 2017 JLL Research Report Time for Thu Thiem The largest mixed-use inner city development in Southeast Asia Key takeaways from this report 1. Time to buy residential units A. Acquire land from an existing owner that has Figure 1: Old CBD v.s. new CBD prime apartment selling price been allocated land. Residential prices in Thu Thiem are currently trading at US$/sqm 30-35 percent discount below District 1 levels. In Shanghai, B. Form a joint venture (JV) with a local partner who 30,000 apartment prices in Pudong are 43 percent above Puxi, the has been allocated land. old CBD and Bonifacio prices are the same as Makati. Over C. Enter bidding process for the land that has yet to 25,000 time, we expect Thu Thiem to follow a similar trend. be allocated. 43% 2. “Tipping point” for office development 5. Phasing 20,000 With lack of supply and increasing rents in the existing CBD, It is important to note that Thu Thiem is 657 hectares, with and the completion of a major infrastructure within Thu 20,426 residential units and 3.4 million square metres of 15,000 Thiem, we anticipate large head office requirements will commercial space. It is critically important that developers start to consider Thu Thiem as a viable alternative to the pay careful attention to market conditions and supply and 10,000 existing CBD. demand dynamics to limit the risk of oversupply in the future. 3. Lack of government funding and incentives 6. Long term construction site 5,000 0% -34% Unlike other new urban development area in other countries, It is inevitable on a large mixed-use development site that the lack of preferential policies/incentives are the biggest the area will be a construction site for a number of years.