Democracy in Default?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Method to Accommodate Backward Compatibility on the Learning Application-Based Transliteration to the Balinese Script

(IJACSA) International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, Vol. 12, No. 6, 2021 A Method to Accommodate Backward Compatibility on the Learning Application-based Transliteration to the Balinese Script 1 3 4 Gede Indrawan , I Gede Nurhayata , Sariyasa I Ketut Paramarta2 Department of Computer Science Department of Balinese Language Education Universitas Pendidikan Ganesha (Undiksha) Universitas Pendidikan Ganesha (Undiksha) Singaraja, Indonesia Singaraja, Indonesia Abstract—This research proposed a method to accommodate transliteration rules (for short, the older rules) from The backward compatibility on the learning application-based Balinese Alphabet document 1 . It exposes the backward transliteration to the Balinese Script. The objective is to compatibility method to accommodate the standard accommodate the standard transliteration rules from the transliteration rules (for short, the standard rules) from the Balinese Language, Script, and Literature Advisory Agency. It is Balinese Language, Script, and Literature Advisory Agency considered as the main contribution since there has not been a [7]. This Bali Province government agency [4] carries out workaround in this research area. This multi-discipline guidance and formulates programs for the maintenance, study, collaboration work is one of the efforts to preserve digitally the development, and preservation of the Balinese Language, endangered Balinese local language knowledge in Indonesia. The Script, and Literature. proposed method covered two aspects, i.e. (1) Its backward compatibility allows for interoperability at a certain level with This study was conducted on the developed web-based the older transliteration rules; and (2) Breaking backward transliteration learning application, BaliScript, for further compatibility at a certain level is unavoidable since, for the same ubiquitous Balinese Language learning since the proposed aspect, there is a contradictory treatment between the standard method reusable for the mobile application [8], [9]. -

Thinking with Type

ellen lupton thinking with a critical guide typefor designers, writers, editors & students princeton architectural press . new york TEXT LEITERS GATHER INTO WORDS, WORDS BUILD INTO SENTENCES. In typography, "text" is defined as an ongoing sequence of words, distinct from shorter headlines or captions. The main block is often called the "body," comprising the principal mass of content. Also known as "running text," it can flow from one page, column, or box to another. Text can be viewed as a thing-a sound and sturdy object-or a fluid poured into the containers of page or screen. Text can be solid or liquid, body or blood. As body, text has more integrity and wholeness than the elements that surround it, from pictures, captions, and page numbers to banners, buttons, and menus. Designers generally treat a body of text consistently, letting it appear as a coherent substance that is distributed across the spaces of a CYBERSPACE AND CIVIL document. In digital media, long texts are typically broken into chunks that SOCIETY Poster, 19 96. Designer: Hayes Henderson. can be accessed by search engines or hypertext links. Contemporary Rather than represent designers and writers produce content for various contexts, from the pages cyberspace as an ethereal grid, of print to an array of software environments, screen conditions, and digital the designer has used blotches devices, each posing its own limits and opportunities. of overlapping text to build an ominous, looming body. Designers provide ways into-and out of-the flood of words by breaking up text into pieces and offering shortcuts and alternate routes through masses of information. -

Speaker Biographies

SPEAKER BIOGRAPHIES Speakers: Dr. Deborah Anderson, Researcher, Dept. of Linguistics, UC Berkeley Deborah (Debbie) Anderson is a Researcher in the Department of Linguistics at UC Berkeley. Since 2002, she has run the Script Encoding Initiative project, which helps get scripts and characters into the Unicode Standard. She also represents UC Berkeley in the Unicode Technical Committee meetings and is a member of the US National Body in ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2. In addition, she is a Unicode Technical Director. Zibi Braniecki, Mozilla, Sr. Staff Platform Engineer Zibi Braniecki is a Sr. Staff Platform Engineer at Mozilla working on internationalization and localization of Gecko and Firefox. Zibi represents Mozilla at TC39 committee and is championing multiple ECMA402 proposals. When not in front of the keyboard, he's captaining the Polish National Team in Ultimate Frisbee. Shane Carr, Senior Software Engineer, Internationalization, Google, Inc. Shane Carr is a Senior Software Engineer on Google's i18n Engineering team. He is chair of the ECMA 402 subcommittee for JavaScript i18n standards and is a core contributor to the International Components for Unicode (ICU) project. His work on ICU has focused on locale data, number formatting, and performance optimization. Shane has previously presented on Zawgyi and on ICU number formatting at the 41st and 42nd Internationalization & Unicode Conference (IUC). He has also presented at the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML) and the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Institute of Chemical Engineers (AIChE). He holds an MS and BS in Computer Science and BS in Chemical Engineering summa cum laude from Washington University in St. -

4.4. Is Unicode Font Available? 14 4.4.1

1 Contents 1. Introduction 3 1.1. Who we are 3 1.2. The UNESCO and IYIL initiative 4 2. Process overview 4 2.1. Language Status Workflow 5 2.2. Technology Implementation Workflow 6 3. Language Status 7 3.1. Is language currently used by a community? 7 3.2. Is language intended for active community use? 7 3.2.1. Revitalize language 7 3.3. Is language in a public registry? 8 3.4. Is language written? 8 3.4.1. Develop written form 8 3.4.2. Document language 8 3.4.2.1. Language is documented 8 3.4.2.2. Language is not documented 9 3.5. Does language use a consistent writing system? 9 3.5.1. Are the characters used already supported? 9 3.6. Is writing supported by a standard? 10 3.6.1. Submit character proposals 10 3.6.2. Develop standard 11 3.7. Proceed to implementation 11 4. Language Technology Implementation Workflow 11 4.1 Note on technology for text in digital systems 11 4.2. Definitions for implementing digital support 12 4.3. Standard language code available? 13 4.3.1. Apply for language code 13 4.4. Is Unicode font available? 14 4.4.1. Create font 14 4.5. Is font available on devices? 14 4.5.1. Manual install or ask vendors for support 14 4.6. Does device have input support? 15 4.7. Is input supported by third party apps or devices? 15 4.7.1. Develop input method 15 4.8. Does device have Unicode data support? 16 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License 2 5. -

The Emergence and Erasure of !New Thinking! Within Graphic Design

! ! ∀ ## ∃%& ∋(∀∀∋)∗∋ ∃ ∀++ +,−(+ doi:10.1093/jdh/epr023 Journal of Design History Lost in Translation: The Emergence Vol. 24 No. 3 and Erasure of ‘New Thinking’ within Graphic Design Criticism in the 1990s Julia Moszkowicz Downloaded from This article revisits the early 1990s, identifying examples of critical journalism that introduced the idea of ‘new thinking’ in American graphic design to a British audience. Whilst such thinking is articulated in terms of postmodern and post-structuralist tenets, it will be argued that the distinct visual style of postmodern artefacts belies an eclectic philosophical constitution. In the process of describing emergent American practices at http://jdh.oxfordjournals.org/ Cranbrook Academy of Art in this period, for example, Ellen Lupton argues for a distinction to be made between intellectual (post-structuralist) and superficial (postmodern) approaches to visual form. This paper indicates, however, that in spite of this initial attention to distinct methodological concerns, there has been a tendency to oversimplify the postmodern story in graphic design writing and to use historical sources in highly selective ways. Indeed, close examination of texts from the period reveals how new thinking in America is underpinned by a complex range of philosophical ideas, with the (seemingly) contradictory impulse of phenomenology, in particular, making a at Southampton Solent University on November 11, 2013 dominant contribution to the mix. This article argues that it is time to reverse these reductive tendencies in British criticism and to reinvigorate its understanding of this transformative period with a return to these postmodern sources. Keywords: design criticism—design journalism—graphic design—postmodernism—post- structuralism—pragmatic design This article considers the critical reception of postmodern graphic design within the international journal, Eye, when a wave of ‘new thinking’ crossed the Atlantic and was reviewed by this influential publication in the 1990s. -

Thinking with Type : a Critical Guide for Designers, of Princeton Architectural Press Writers, Editors, & Students / Ellen Lupton

4YPOGRAPHYISWHATLANGUAGELOOKSLIKE Dedicated to george sadek (1928–2007) and all my teachers. ELLENLUPTON THINKING WITH ACRITICALGUIDE TYPEFORDESIGNERS WRITERS EDITORS STUDENTS princeton architectural press . new york Published by book designer Princeton Architectural Press Ellen Lupton 37 East Seventh Street editor New York, New York 10003 First edition: Mark Lamster Second edition: Nicola Bednarek For a free catalog of books, call 1.800.722.6657. Visit our web site at www.papress.com. cover designers Jennifer Tobias and Ellen Lupton © 2004, 2010 Princeton Architectural Press divider pages Princeton Architectural Press Paintings by Ellen Lupton All rights reserved photographer Second, revised and expanded edition Dan Meyers No part of this book may be used or reproduced in primary typefaces any manner without written permission from the Scala Pro, designed by Martin Majoor publisher, except in the context of reviews. Thesis, designed by Luc(as) de Groot Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify special thanks to owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be Nettie Aljian, Bree Anne Apperley, Sara Bader, Janet Behning, corrected in subsequent editions. Becca Casbon, Carina Cha, Tom Cho, Penny (Yuen Pik) Chu, Carolyn Deuschle, Russell Fernandez, Pete Fitzpatrick, Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wendy Fuller, Jan Haux, Linda Lee, Laurie Manfra, John Myers, Katharine Myers, Steve Royal, Dan Simon, Andrew Stepanian, Lupton, Ellen. Jennifer Thompson, Paul Wagner, Joe Weston, and Deb Wood Thinking with type : a critical guide for designers, of Princeton Architectural Press writers, editors, & students / Ellen Lupton. — 2nd —Kevin C. Lippert, publisher rev. and expanded ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-56898-969-3 (alk. -

Referência Debian I

Referência Debian i Referência Debian Osamu Aoki Referência Debian ii Copyright © 2013-2021 Osamu Aoki Esta Referência Debian (versão 2.85) (2021-09-17 09:11:56 UTC) pretende fornecer uma visão geral do sistema Debian como um guia do utilizador pós-instalação. Cobre muitos aspetos da administração do sistema através de exemplos shell-command para não programadores. Referência Debian iii COLLABORATORS TITLE : Referência Debian ACTION NAME DATE SIGNATURE WRITTEN BY Osamu Aoki 17 de setembro de 2021 REVISION HISTORY NUMBER DATE DESCRIPTION NAME Referência Debian iv Conteúdo 1 Manuais de GNU/Linux 1 1.1 Básico da consola ................................................... 1 1.1.1 A linha de comandos da shell ........................................ 1 1.1.2 The shell prompt under GUI ......................................... 2 1.1.3 A conta root .................................................. 2 1.1.4 A linha de comandos shell do root ...................................... 3 1.1.5 GUI de ferramentas de administração do sistema .............................. 3 1.1.6 Consolas virtuais ............................................... 3 1.1.7 Como abandonar a linha de comandos .................................... 3 1.1.8 Como desligar o sistema ........................................... 4 1.1.9 Recuperar uma consola sã .......................................... 4 1.1.10 Sugestões de pacotes adicionais para o novato ................................ 4 1.1.11 Uma conta de utilizador extra ........................................ 5 1.1.12 Configuração -

Wesley Stuckey 1-2

WESLEY STUCKEY 1-2 11 W Branch Ln | Baltimore, MD 21201 | 601.953.0176 [email protected] | www.wesleystuckey.com EDUCATION Maryland Institute College of Art Master of Fine Art in Graphic Design Baltimore, Maryland | May 2011 Mississippi State University Bachelor of Fine Arts in Printmaking and Graphic Design Starkville, Mississippi | December 2006 SKILLS / SOFTWARE Software / Languages Adobe Creative Suite, HTML5, CSS3, JQUERY, PHP Printing Methods Letterpress, Serigraphy, Intaglio, Monoprinting, Wood Block and Linoleum Relief, Gum Arabic Dichromate, Wet Lab and Digital Photography. JOB EXPERIENCE / INTERNSHIPS Stuckey Design Creative Director, Owner May 2008 - Present Maryland Institute College of Art Adjunct Professor of Graphic Design August 2014 - Present University of Maryland in Baltimore County Adjunct Professor of Graphic Design August 2011 - May 2015 MGH Modern Marketing Interactive Art Director June 2011 - November 2012 Maryland Institute College of Art Graphic Design Graduate Teaching Intern / Dolphin Press and Print Graduate Intern August 2009 - May 2011 Mississippi Children’s Museum Graphic Designer September 2008 - December 2010 The University of Southern Mississippi / Department of Printing and Creative Services Graphic Designer January 2008 - August 2009 Mississippi State University / Department of Art Printmaking Teaching Assistant / Lab Monitor / Freelance Printer August 2005 - February 2009 WESLEY STUCKEY 2-2 LECTURES / TALKS SEAM Conference Workshop: Sense of Space - Defining Place and Marking the Mark! | March -

Pdflib-9.3.1-Tutorial.Pdf

ABC PDFlib, PDFlib+PDI, PPS A library for generating PDF on the fly PDFlib 9.3.1 Tutorial For use with C, C++, Java, .NET, .NET Core, Objective-C, Perl, PHP, Python, RPG, Ruby Copyright © 1997–2021 PDFlib GmbH and Thomas Merz. All rights reserved. PDFlib users are granted permission to reproduce printed or digital copies of this manual for internal use. PDFlib GmbH Franziska-Bilek-Weg 9, 80339 München, Germany www.pdflib.com phone +49 • 89 • 452 33 84-0 [email protected] [email protected] (please include your license number) This publication and the information herein is furnished as is, is subject to change without notice, and should not be construed as a commitment by PDFlib GmbH. PDFlib GmbH assumes no responsibility or lia- bility for any errors or inaccuracies, makes no warranty of any kind (express, implied or statutory) with re- spect to this publication, and expressly disclaims any and all warranties of merchantability, fitness for par- ticular purposes and noninfringement of third party rights. PDFlib and the PDFlib logo are registered trademarks of PDFlib GmbH. PDFlib licensees are granted the right to use the PDFlib name and logo in their product documentation. However, this is not required. PANTONE® colors displayed in the software application or in the user documentation may not match PANTONE-identified standards. Consult current PANTONE Color Publications for accurate color. PANTONE® and other Pantone, Inc. trademarks are the property of Pantone, Inc. © Pantone, Inc., 2003. Pantone, Inc. is the copyright owner of color data and/or software which are licensed to PDFlib GmbH to distribute for use only in combination with PDFlib Software. -

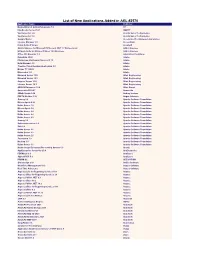

List of New Applications Added in ARL #2570

List of New Applications Added in ARL #2570 Application Name Publisher Nomad Branch Admin Extensions 7.0 1E FineReader Server 14.1 ABBYY VoxConverter 2.0 Acarda Sales Technologies VoxConverter 3.0 Acarda Sales Technologies Sample Master Accelerated Technology Laboratories License Manager 3.5 AccessData Prizm ActiveX Viewer AccuSoft Add-in Express for Microsoft Office and .NET 7.7 Professional Add-in Express Ultimate Suite for Microsoft Excel 18.5 Business Add-in Express Office 365 Reporter 3.5 AdminDroid Solutions RoboHelp 2020 Adobe Photoshop Lightroom Classic CC 10 Adobe Help Manager 4.0 Adobe Creative Cloud Desktop Application 5.3 Adobe Bridge CC (2021) Adobe Dimension 3.4 Adobe Monarch Server 15.0 Altair Engineering Monarch Server 15.3 Altair Engineering Angoss Server 10.4 Altair Engineering License Server 14.1 Altair Engineering ARGUS Enterprise 12.0 Altus Group Anaconda 2020.07 Anaconda SMath Studio 0.98 Andrey Ivashov PDFTK Builder 3.10 Angus Johnson Groovy 2.6 Apache Software Foundation Mesos Agent 0.28 Apache Software Foundation Kafka Server 1.0 Apache Software Foundation Mesos Agent 1.8 Apache Software Foundation Kafka Server 2.4 Apache Software Foundation Kafka Server 2.6 Apache Software Foundation Kafka Server 2.3 Apache Software Foundation Groovy 2.5 Apache Software Foundation Subversion server 1.9 Apache Software Foundation Solr 2.0 Apache Software Foundation Kafka Server 2.1 Apache Software Foundation Kafka Server 2.2 Apache Software Foundation Kafka Server 2.5 Apache Software Foundation Cassandra 3.9 Apache Software Foundation -

Pdflib Tutorial 9.2.0

ABC PDFlib, PDFlib+PDI, PPS A library for generating PDF on the fly PDFlib 9.2.0 Tutorial For use with C, C++, COM, Java, .NET, Objective-C, Perl, PHP, Python, RPG, Ruby Copyright © 1997–2019 PDFlib GmbH and Thomas Merz. All rights reserved. PDFlib users are granted permission to reproduce printed or digital copies of this manual for internal use. PDFlib GmbH Franziska-Bilek-Weg 9, 80339 München, Germany www.pdflib.com phone +49 • 89 • 452 33 84-0 If you have questions check the PDFlib mailing list and archive at groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/pdflib/info Licensing contact: [email protected] Support for commercial PDFlib licensees: [email protected] (please include your license number) This publication and the information herein is furnished as is, is subject to change without notice, and should not be construed as a commitment by PDFlib GmbH. PDFlib GmbH assumes no responsibility or lia- bility for any errors or inaccuracies, makes no warranty of any kind (express, implied or statutory) with re- spect to this publication, and expressly disclaims any and all warranties of merchantability, fitness for par- ticular purposes and noninfringement of third party rights. PDFlib and the PDFlib logo are registered trademarks of PDFlib GmbH. PDFlib licensees are granted the right to use the PDFlib name and logo in their product documentation. However, this is not required. PANTONE® colors displayed in the software application or in the user documentation may not match PANTONE-identified standards. Consult current PANTONE Color Publications for accurate color. PANTONE® and other Pantone, Inc. trademarks are the property of Pantone, Inc. -

The Rise of Research in Graphic Design

Introduction: The Rise of Research in Graphic Design AUDREY BENNETT Graphic design is at a crossroads. Looking back, one sees designers engaged in a process where intuition informs the development of visual rhetoric intended to evoke a response from a target audience. Looking ahead, one sees them engaged in a process where research is integrated into the design of objects and experiences for and with the audience. By adopting interdisciplinary research approaches, graphic designers can both question and agrm their intuitive inclinations, and place this process in conversation with peers and even the lay public. Traditionally graphic design theory has privileged intuition and creativity over empirical research. This book seeks to provide an alternative approach to graphic design theory by surveying the best work, past to present, on research- based graphic design theory. The question then is: what are graphic design’s theories? It can be argued that the art-based principles of graphic design—including (but not limited to) contrast, hierarchy, repetition, alignment, and color—are in fact theories proven through a long history of successful experimentation in practice.1 Indeed, graphic designers—through professional practice— have tested and retested to the point where it makes sense to refer to these theories as laws or principles. Marty Neumeier’s and James Souttar’s analyses of the work of John Rushworth, Massimo Vignelli, 16 Nancy Skolos, and Chuck Close, confirm the replicability of these principles to create aesthetics that sell ideas, products, and experiences.2 Yet within the discipline of graphic design these principles are not regarded as “proven” theories because graphic design historically lacks a strong research agenda.