Fall 2019 the Cooper Union for the Advancement Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEDIA UPDATES3 30.Pdf

Dean *Anthony Vidler to receive ACSA Centennial Award The Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA) announced today that Anthony Vidler will receive a special Centennial Award at next week’s 100th ACSA Annual Meeting in Boston. Anthony Vidler is Dean and Professor at the Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture of The Cooper Union, where he has served since 2001. The Centennial Award was created by the ACSA Board of Directors in recognition of Dean Vidler’s wide ranging contributions to architectural education. Says Judith Kinnard, FAIA, ACSA president: “Anthony Vidler’s teaching and scholarship have had a major impact on architectural education. We invited him to receive this special award during our 100th anniversary and give the keynote lecture because of his extraordinary ability to link current issues in architecture and urbanism to a broad historic trajectory. His work forces us to question our assumptions as we engage contemporary conditions as designers.” Anthony Vidler received his professional degree in architecture from Cambridge University in England, and his doctorate in History and Theory from the University of Technology, Delft, the Netherlands. Dean Vidler was a member of the Princeton University School of Architecture faculty from 1965 to 1993, serving as the William R. Kenan Jr. Chair of Architecture, the Chair of the Ph.D. Committee, and Director of the Program in European Cultural Studies. In 1993 he took up a position as professor and Chair of the Department of Art History at the University of California, Los Angeles, with a joint appointment in the School of Architecture from 1997. -

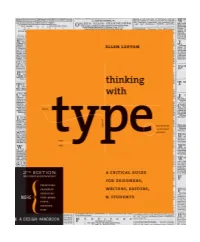

Thinking with Type

ellen lupton thinking with a critical guide typefor designers, writers, editors & students princeton architectural press . new york TEXT LEITERS GATHER INTO WORDS, WORDS BUILD INTO SENTENCES. In typography, "text" is defined as an ongoing sequence of words, distinct from shorter headlines or captions. The main block is often called the "body," comprising the principal mass of content. Also known as "running text," it can flow from one page, column, or box to another. Text can be viewed as a thing-a sound and sturdy object-or a fluid poured into the containers of page or screen. Text can be solid or liquid, body or blood. As body, text has more integrity and wholeness than the elements that surround it, from pictures, captions, and page numbers to banners, buttons, and menus. Designers generally treat a body of text consistently, letting it appear as a coherent substance that is distributed across the spaces of a CYBERSPACE AND CIVIL document. In digital media, long texts are typically broken into chunks that SOCIETY Poster, 19 96. Designer: Hayes Henderson. can be accessed by search engines or hypertext links. Contemporary Rather than represent designers and writers produce content for various contexts, from the pages cyberspace as an ethereal grid, of print to an array of software environments, screen conditions, and digital the designer has used blotches devices, each posing its own limits and opportunities. of overlapping text to build an ominous, looming body. Designers provide ways into-and out of-the flood of words by breaking up text into pieces and offering shortcuts and alternate routes through masses of information. -

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art Atcooper 2 | the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art

Winter 2008/09 The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art atCooper 2 | The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art Message from President George Campbell Jr. Union The Cooper Union has a history characterized by extraordinary At Cooper Union resilience. For almost 150 years, without ever charging tuition to a Winter 2008/09 single student, the college has successfully weathered the vagaries of political, economic and social upheaval. Once again, the institution Message from the President 2 is facing a major challenge. The severe downturn afflicting the glob- al economy has had a significant impact on every sector of American News Briefs 3 U.S. News & World Report Ranking economic activity, and higher education is no exception. All across Daniel and Joanna Rose Fund Gift the country, colleges and universities are grappling with the prospect Alumni Roof Terrace of diminished resources from two major sources of funds: endow- Urban Visionaries Benefit ment and contributions. Fortunately, The Cooper Union entered the In Memory of Louis Dorfsman (A’39) current economic slump in its best financial state in recent memory. Sue Ferguson Gussow (A’56): As a result of progress on our Master Plan in recent years, Cooper Architects Draw–Freeing the Hand Union ended fiscal year 2008 in June with the first balanced operat- ing budget in two decades and with a considerably strengthened Features 8 endowment. Due to the excellent work of the Investment Committee Azin Valy (AR’90) & Suzan Wines (AR’90): Simple Gestures of our Board of Trustees, our portfolio continues to outperform the Ryan (A’04) and Trevor Oakes (A’04): major indices, although that is of little solace in view of diminishing The Confluence of Art and Science returns. -

The Emergence and Erasure of !New Thinking! Within Graphic Design

! ! ∀ ## ∃%& ∋(∀∀∋)∗∋ ∃ ∀++ +,−(+ doi:10.1093/jdh/epr023 Journal of Design History Lost in Translation: The Emergence Vol. 24 No. 3 and Erasure of ‘New Thinking’ within Graphic Design Criticism in the 1990s Julia Moszkowicz Downloaded from This article revisits the early 1990s, identifying examples of critical journalism that introduced the idea of ‘new thinking’ in American graphic design to a British audience. Whilst such thinking is articulated in terms of postmodern and post-structuralist tenets, it will be argued that the distinct visual style of postmodern artefacts belies an eclectic philosophical constitution. In the process of describing emergent American practices at http://jdh.oxfordjournals.org/ Cranbrook Academy of Art in this period, for example, Ellen Lupton argues for a distinction to be made between intellectual (post-structuralist) and superficial (postmodern) approaches to visual form. This paper indicates, however, that in spite of this initial attention to distinct methodological concerns, there has been a tendency to oversimplify the postmodern story in graphic design writing and to use historical sources in highly selective ways. Indeed, close examination of texts from the period reveals how new thinking in America is underpinned by a complex range of philosophical ideas, with the (seemingly) contradictory impulse of phenomenology, in particular, making a at Southampton Solent University on November 11, 2013 dominant contribution to the mix. This article argues that it is time to reverse these reductive tendencies in British criticism and to reinvigorate its understanding of this transformative period with a return to these postmodern sources. Keywords: design criticism—design journalism—graphic design—postmodernism—post- structuralism—pragmatic design This article considers the critical reception of postmodern graphic design within the international journal, Eye, when a wave of ‘new thinking’ crossed the Atlantic and was reviewed by this influential publication in the 1990s. -

Thinking with Type : a Critical Guide for Designers, of Princeton Architectural Press Writers, Editors, & Students / Ellen Lupton

4YPOGRAPHYISWHATLANGUAGELOOKSLIKE Dedicated to george sadek (1928–2007) and all my teachers. ELLENLUPTON THINKING WITH ACRITICALGUIDE TYPEFORDESIGNERS WRITERS EDITORS STUDENTS princeton architectural press . new york Published by book designer Princeton Architectural Press Ellen Lupton 37 East Seventh Street editor New York, New York 10003 First edition: Mark Lamster Second edition: Nicola Bednarek For a free catalog of books, call 1.800.722.6657. Visit our web site at www.papress.com. cover designers Jennifer Tobias and Ellen Lupton © 2004, 2010 Princeton Architectural Press divider pages Princeton Architectural Press Paintings by Ellen Lupton All rights reserved photographer Second, revised and expanded edition Dan Meyers No part of this book may be used or reproduced in primary typefaces any manner without written permission from the Scala Pro, designed by Martin Majoor publisher, except in the context of reviews. Thesis, designed by Luc(as) de Groot Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify special thanks to owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be Nettie Aljian, Bree Anne Apperley, Sara Bader, Janet Behning, corrected in subsequent editions. Becca Casbon, Carina Cha, Tom Cho, Penny (Yuen Pik) Chu, Carolyn Deuschle, Russell Fernandez, Pete Fitzpatrick, Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wendy Fuller, Jan Haux, Linda Lee, Laurie Manfra, John Myers, Katharine Myers, Steve Royal, Dan Simon, Andrew Stepanian, Lupton, Ellen. Jennifer Thompson, Paul Wagner, Joe Weston, and Deb Wood Thinking with type : a critical guide for designers, of Princeton Architectural Press writers, editors, & students / Ellen Lupton. — 2nd —Kevin C. Lippert, publisher rev. and expanded ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-56898-969-3 (alk. -

Inventing the I-Beam: Richard Turner, Cooper & Hewitt and Others

Inventing the I-Beam: Richard Turner, Cooper &Hewitt and Others Author(s): Charles E. Peterson Source: Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology, Vol. 12, No. 4 (1980), pp. 3-28 Published by: Association for Preservation Technology International (APT) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1493818 . Accessed: 17/09/2013 16:52 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Association for Preservation Technology International (APT) is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.59.130.200 on Tue, 17 Sep 2013 16:52:33 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions APTVol. X11N' 4 1980 INVENTINGTHE I-BEAM: RICHARDTURNER, COOPER & HEWITTAND OTHERS' by CharlesE. Peterson,F.A.I.A.* Forwell over a centurythe I-beam,rolled first in wroughtiron -the bulb-tee used from1848 on forsupporting fireproof brick and then in steel, has been one of the most widely used building floorsand ceilings. By 1856 a trueI-beam was rolledat Trenton, elementsever invented. The story of itsdevelopment is stillobscure New Jerseyand it was at once adoptedfor the new Federalbuild- at severalpoints. -

1,545 Sf Retail Space Available 27 Saint Marks Place | East Village, Ny

BETWEEN SECOND & THIRD AVENUES 1,545 SF RETAIL SPACE AVAILABLE 27 SAINT MARKS PLACE | EAST VILLAGE, NY Great Restaurant/QSR Potential 1,545 SF COMING SOON AVAILABLE DAVID SINGER DAVID YABLON Sales Associate Director [email protected] [email protected] (212) 257-5061 (212) 433-1986 Blue Meadow Flowers Purse Props City of Saints Coffee Roasters Blockheads Kollegie Third North Courtyard Cafe 12th Street Ale House Sundaes and Cones Ippudo NY Turntable ab Ruby’s Cafe HIGHLIGHTS Kotobuki E 11 Happy Bowls NYC Black & hite TH STREET Bar Veloce Prime retailEast Village space Thrift Shop available on bustling Saint Marks Place between Second & E 12 Third Avenues in the East Village.TH The space has 12’ of frontage, 10’ ceilings Ikinari Steak John’s of 12th Street STREET and ampleCacio e Pepe basement storage. Potential for venting. Yuba Kanoyama Motorino The Central Bar POSSESSIONNumero 28 Pizzeria ASKING PRICE E 10 E 8 TH Immediate Upon Request TH AVENUE STREET STREET RD 3 Bluestone ane Abacus Pharmacy Tribe AFAYETTE STREET ASTOR PLACE SUWA STATION 4 6 5,111,358 RIDERS ANNUALL RETAIL SPACE AVAILABLEPULIC SCOOL 1 STUYVESANT STREET Pan Ya EAST E Yuan Dim Sum King TH 1,545 SF Ground Casey Rubber Stamps STREET 212 Hisae’s 800 SF Cellar Tokyo Joe The Alley Klong U2 Karaoke Chikaicious Dessert Bar Buffalo Echange Boka Yakitori Taisho Solas Kingston Hall Veniero’s Pasticceria & Caffe imited to One Record Shop TE GREAT ALL Udon est Cha-An Teahouse The 13th Step Ray’s Pizza & Bagel AVENUE NEIGHBORS AT COOPER UNION Cloister Cafe ND Iggy’s Pizzeria HairMates St. -

St. Marks Place 5Th Floor, East Village Nyc

6 RETAIL FOR LEASE ST. MARKS PLACE 5TH FLOOR, EAST VILLAGE NYC Between Second & Third Avenues APPROXIMATE SIZE 5th Floor: 3000 SF ASKING RENT TERM $10,000/Month Long Term $8,000/Month POSSESSION FRONTAGE Immediate 26 FT COMMENTS • Brand new renovation • Private entrance elevator • Steps from Astor Place, NYU, Cooper Union, as well as the hottest restaurants and nightlife in NYC NEIGHBORS New York University • Cooper Union • Starbucks • Dunkin’ • Ben & Jerry’s • Mamoun’s • Kung Fu Tea • Veselka TRANSPORTATION JAMES FAMULARO BEN BIBERAJ JACK MOSSERI President Director Associate [email protected] [email protected] 703.434.1461 212.468.5976 All information supplied is from sources deemed reliable and is furnished subject to errors, omissions, modifications, removal of the listing from sale or lease, and to any listing conditions, including the rates and manner of payment of commissions for particular offerings imposed by Meridian Capital Group. This information may include estimates and projections prepared by Meridian Capital Group with respect to future events, and these future events may or may not actually occur. Such estimates and projections reflect various assumptions concerning anticipated results. While Meridian Capital Group believes these assumptions are reasonable, there can be no assurance that any of these estimates and projections will be correct. Therefore, actual results may vary materially from these estimates and projections. Any square footage dimensions set forth are approximate. 6 ST. MARKS PLACE 5TH FLOOR, EAST VILLAGE, NYC | Between Second & Third Avenues RETAIL FOR LEASE INTERIOR JAMES FAMULARO BEN BIBERAJ JACK MOSSERI President Director Associate [email protected] [email protected] 703.434.1461 212.468.5976 All information supplied is from sources deemed reliable and is furnished subject to errors, omissions, modifications, removal of the listing from sale or lease, and to any listing conditions, including the rates and manner of payment of commissions for particular offerings imposed by Meridian Capital Group. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25

NYU Urban Design and Architecture Studies New York Area Calendar of Events January 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Past, Present, and Future Tour Design and the Just City in NYC Underground Manhattan, The History of the NYC Subway System 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Marina Tabassum: Happy 50th Past, Present, and Dwelling in the Anniversary, St. Future Tour Ganges Delta Mark’s Historic District! In Our Time: A Year of Architecture in a Day 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Contested Ground: Affordable Design Past, Present, and Design and the and Beyond: Future Tour Politics of Memory Addressing the Needs of All Behind-the-Ropes: Classical New Populations Insider’s Tours of the York: Discovering Merchant’s House Greece and Rome in Lower Manhattan 27 28 29 30 31 Buromoscow Drawing Codes: Just Another Brick Inside Out/Outside Gallery Roundtable in the Wall In: Second Nature The Making of the in Japanese Greenwich Village Presentation for Architecture Historic District League Grants Events The Municipal Art Society of New York SEE ALL EVENTS → WED 9 School Program Tour Bernard and Anne Spitzer School of Architecture Learn about the Spitzer School’s undergraduate and graduate programs. This tour will include the studios, fabrication shop, library, and Solar Roof pod. EVENT TYPE Graduate Program Tour DATE & TIME Wednesday, January 9th | 3:30 – 4:30 PM VENUE Bernard and Anne Spitzer School of Architecture 141 Convent Avenue New York, NY 10031 FEE Free and open to the public REGISTER Education Design for the Homeless Gary Armbruster, AIA, ALEP, Principal Architect and Partner, MA+ Architecture Amy Brewer, M.Ed., Director of Education, Positive Tomorrows Angela M. -

Wesley Stuckey 1-2

WESLEY STUCKEY 1-2 11 W Branch Ln | Baltimore, MD 21201 | 601.953.0176 [email protected] | www.wesleystuckey.com EDUCATION Maryland Institute College of Art Master of Fine Art in Graphic Design Baltimore, Maryland | May 2011 Mississippi State University Bachelor of Fine Arts in Printmaking and Graphic Design Starkville, Mississippi | December 2006 SKILLS / SOFTWARE Software / Languages Adobe Creative Suite, HTML5, CSS3, JQUERY, PHP Printing Methods Letterpress, Serigraphy, Intaglio, Monoprinting, Wood Block and Linoleum Relief, Gum Arabic Dichromate, Wet Lab and Digital Photography. JOB EXPERIENCE / INTERNSHIPS Stuckey Design Creative Director, Owner May 2008 - Present Maryland Institute College of Art Adjunct Professor of Graphic Design August 2014 - Present University of Maryland in Baltimore County Adjunct Professor of Graphic Design August 2011 - May 2015 MGH Modern Marketing Interactive Art Director June 2011 - November 2012 Maryland Institute College of Art Graphic Design Graduate Teaching Intern / Dolphin Press and Print Graduate Intern August 2009 - May 2011 Mississippi Children’s Museum Graphic Designer September 2008 - December 2010 The University of Southern Mississippi / Department of Printing and Creative Services Graphic Designer January 2008 - August 2009 Mississippi State University / Department of Art Printmaking Teaching Assistant / Lab Monitor / Freelance Printer August 2005 - February 2009 WESLEY STUCKEY 2-2 LECTURES / TALKS SEAM Conference Workshop: Sense of Space - Defining Place and Marking the Mark! | March -

Cost $166-Million

THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION November 13, 2011 Cooper Union, Bastion of Free Arts Education for the Deserving, Mulls Tuition By Scott Carlson *Jamshed Bharucha, Cooper Union's new president, stands in front of a statue of Peter Cooper, the wealthy philanthropist for whom the college was named. Last year Cooper Union ran a budget deficit of about 27 percent. Mark Abramson for The Chronicle The last time Cooper Union charged tuition to a full-time student was in 1902. Around then, Andrew Carnegie gave the college a gift that would allow it to meet the wish of its founder to make education as "free as air and water," as Peter Cooper had put it. Students here—in the college's well-known programs in the arts, engineering, and architecture—are selected based on talent and promise, not on what they can pay. At a time when tuition at some colleges has reached stratospheric amounts, Cooper Union's cherished and lofty educational ethic is quite unusual in academe. And it is also endangered. On Halloween night here in the East Village, Cooper Union's students gathered to hear Jamshed Bharucha, who has been president for merely four months, lay out some staggering facts about the institution's finances: For years, the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art has been burning through the unrestricted part of its endowment to cover shortfalls in its budget, and his administration predicts that the cushion will be gone in two to three years. Cooper Union's new academic building, designed by the star architect Thom Mayne, is a landmark—and cost $166- million. -

On Error at the Buffalo School of Architecture An

Assistant Professor Adjunct James Lowder participated Assistant Professor Adjunct Michael Samuelian discussed Professor Adjunct Michael Webb was a juror for The in The Banham Symposium: On Error at the Buffalo School the volunteer work in the wake of Hurricane Sandy by the Moleskine Grand Central Terminal Sketchbook held in of Architecture and Planning. New Yorkers for Parks, of which he is a group leader, in the partnership with the Architectural League of New York and article “Coney Island Is Still Devastated, From the Boardwalk the New York Transit Museum. He gave a lecture and Visiting Professor Daniel Meridor , as lead creative for to the Neighborhood Parks,” in the New York Observer . In exhibited his drawings in the Stuckeman School of Studio D Meridor +, has continued working on architectural addition to his volunteer work, Samuelian continues his work Architecture and Landscape Architecture at Penn State designs and recently completed several projects including on the urban planning, design and marketing of the Hudson University as part of the 3W seminar. The participants were a presentation for a new awareness-generating infrastructure Yards project in Midtown Manhattan. Hudson Yards broke Michael Webb, Mark West and James Wines and a that links man-made and natural environments, an innovated ground on its first 50 story, $1.5 billion office tower in symposium at the Drawing Center in New York will feature product design for an audio company, and published the December of 2012. He also worked on the development of an them. He gave a lecture at the School of Architecture at essay “Medianeras/Sidewalls: A Film by Gustavo Taretto” exhibition at the AIA Center for Architecture celebrating the the University of Illinois-Chicago and at The Cooper Union in Framework .