The Alliance for Progress: a Comparative Analysis of Bolivia, Colombia, and Venezuela

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Readercon 14

readercon 14 program guide The conference on imaginative literature, fourteenth edition readercon 14 The Boston Marriott Burlington Burlington, Massachusetts 12th-14th July 2002 Guests of Honor: Octavia E. Butler Gwyneth Jones Memorial GoH: John Brunner program guide Practical Information......................................................................................... 1 Readercon 14 Committee................................................................................... 2 Hotel Map.......................................................................................................... 4 Bookshop Dealers...............................................................................................5 Readercon 14 Guests..........................................................................................6 Readercon 14: The Program.............................................................................. 7 Friday..................................................................................................... 8 Saturday................................................................................................14 Sunday................................................................................................. 21 Readercon 15 Advertisement.......................................................................... 26 About the Program Participants......................................................................27 Program Grids...........................................Back Cover and Inside Back Cover Cover -

Abortlon: the Movie

7- INIL4 Abortlon: The Movie by Dean Markadakis board box covering the television, most students demonstrator looked pensively at the young boy and watched in sordid amazement at the highly manipu- issued a clever little response: "Have you ever seen a A group of pro-life demonstrators gathered at a lated images flashing before them. These images, cow being slaughtered? Have you ever seen a cow's table in the Union last Wednesday, using as their coupled with the heavenly ethereal choir tune play- throat being sliced , its blood drained, beaten and main attention-getter a gruesome 6-minute video ing in the background was enough to bring tears to skinned while it was still alive? I bet if you did, called "The Hard Truth." This video masterpiece, the oculars of even the most avid pro-choice advo- you'd never eat a hamburger again." As far as which, incidentally, does not appear on the shelves cates. grossing me out, this illustration was more than ade- of your local Blockbuster, attempts to portray the As demonstrations go, there was also a small quate. It's true, though-just because something is horror of abortion by showing taped footage of actu- group of counter-demonstrators wielding signs like, not pleasing aesthetically, it is not necessarily moral- al abortions being performed and aborted fetuses in "ABORTION SAVES, JESUS KILLS," and other ly wrong or sinful (or even bad for you). Open-heart jars and garbage cans. There was also literature less offensive slogans. This contingency was a bit surgery, when you think about it, is really gross. -

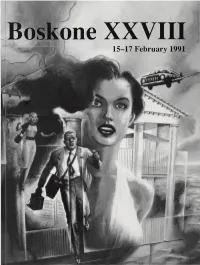

Program Book

Boskone XXVIII 15-17 February 1991 "KUBE-MCDOWELL IS ABLE TO BRING COSMIC IDEASAND HUMAN STORIES TOGETHER IN A WAY PREVIOUSLY ACHIEVED ONLY BY ARTHUR C. CLARKE/' -Orson Scott Card THE QUIET POOLS Michael P. Kube-McDowell AUTHOR OF THE TRICON DISUNITY AND AITERNITIES "A successful, fascinating novel that will leave you much to think about." -ABORIGINAL SCIENCE FICTION it Is late In the 21st century, add mankind Is prepared to launch its most ambitious endeavor: The Diaspora Project, an attempt to colonize a new world beyond our solar system. Out of the entire population on Earth, only 10,000 people will be chosen for the expedltion-the best 10,000. But taking away the brightest may wreak havoc at home. And the Homeworld Movement, led by the mysterious Jeremiah, has refused to let that happen... "Masterfully, Kube-McDowell manages to make us care ...You won't be disappointed; LOCUS $4.50 FROM THE BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF THE JEWELS OF ELVISH AND STORMBLADE SHADOW OF THE SEVENTH MOON Nancy Varian Berberick Long ago, dwarfs peopled the earth, ,- and they lived beneath the shadow of the moon... / z >- Then Man came, with his new • gods and strange ways, to challenge the ancient race. The Dwarfs fell in battle, a generation . - _ forgotten. But gifted with three lifetimes, song-maker Car roc still lives, t jl burdened with the need to share the true :.;jS lineage of his mighty people. < _ As he lifts his " voice in song, one woman rgB hears his . haunting tale Br w of an untold race that fought fiercely to survive.. -

The Rewritten War Alternate Histories of the American Civil War

Title The Rewritten War Alternate Histories of the American Civil War By Renee de Groot Supervised by Dr. George Blaustein Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History: American Studies Program Faculty of Humanities University of Amsterdam 22 August 2016 Declaration I declare that I have read the UvA regulations regarding fraud and plagiarism, and that the following thesis is my original work. Renee de Groot August 22, 2016 Abstract The American Civil War (1861-1865) has provided food for counterfactual speculation for historians, journalists, critics, and writers of all stripes for over a century. What if the Confederacy had won? What if the South had abolished slavery? What if Lincoln had lived? What if…? This thesis offers an anatomy of Civil War alternate history as a distinct though eclectic cultural form. It takes apart the most interesting manifestations and reassembles them to show four intriguing functions of this form: as a platform for challenges to narratives of Civil War memory, for counterintuitive socio-economic criticism, for intricate reflections on history writing and on historical consciousness. It shows the many paradoxes that rule Civil War alternate history: its insularity and global outlook, its essential un-creativity, its ability to attract strange bedfellows and to prod the boundaries between fact and fiction. Most importantly, this thesis demonstrates the marriage of sophistication and banality that characterizes this form that is ultimately the -

כנס ;Quot&מאורות;Quot& בירושלים . 19:30 אביב בשעה תתקיים

בס"ד SCIENCE-Fiction Fanzine Vol. XXVIII, No. 12; December 2016 כנס "מאורות" בירושלים: http://meorot.sf-f.org.il/2016/ חדשות האגודה – דצמבר The Israeli Society for Science Fiction and Fantasy 2016 מועדון הקריאה של חודש דצמבר יעסוק בספר "פרשת ג'יין אייר" מאת ג'ספר פורד )מודן, 2004(. בירושלים יתקיים ביום רביעי 21.12 ב- 19:30, בבית הקפה ״נגילה״, משיח ברוכוף 5, ירושלים. מנחה :שרה מולדובן. בת"א יתקיים ביום חמישי 22.12, ב- 19:30, ב''קפה גרג'', ויצמן 2. מנחה :רונית פוקס אספה כללית ב8- בדצמבר, 2016 תתקיים באשכול הפיס תל אביב בשעה 19:30. כל האירועים של האגודה מופיעים בלוח האירועים )שפע אירועים מעניינים, הרצאות, סדנאות, מפגשים ועוד( לקבלת עדכונים שוטפים על מפגשי מועדון הקריאה ברחבי הארץ ניתן להצטרף לרשימת התפוצה או לדף האגודה בפייסבוק. Society information is available (in Hebrew) at the Society’s site: http://www.sf-f.org.il This month’s roundup: About our new SF friends across the seas in Montreal, Quebec, Canada A special guest contribution: “Alternate History SF: So Many Worlds to Explore” by Shlomo Schwartzberg And, of course, the Sheer Science section by Dr. Doron Calo: Communication by X-Rays! – Your editor, Leybl Botwinik (…and still on the backburner [but getting EVEN closer to realization] the completion of the Zombie series special issue …) Real Reader Remarks: Kudos for the calculation – According to John, this is the 336th issue!!! (actually more – since we also published a few Specials): Well, assuming that you have been putting out monthly issues for 28 years, so 27 x 12 = 324 + 11 this year makes 335. -

Horny Toads and Ugly Chickens: a Bibliography on Texas in Speculative Fiction

HORNY TOADS AND UGLY CHICKENS: A BIBLIOGRAPHY ON TEXAS IN SPECULATIVE FICTION by Bill Page Dellwood Press Bryan, Texas June 2010 1 HORNY TOADS AND UGLY CHICKENS: A BIBLIOGRAPHY ON TEXAS IN SPECULATIVE FICTION by Bill Page In this bibliography I have compiled a list of science fiction, fantasy and horror novels that are set in Texas. I have mentioned several short stories and a few poems and plays in this bibliography, but I did not make any sustained attempt to identify such works. I have not listed works of music, though many songs exist which deal with these subjects. Most entries are briefly annotated, though I well understand that it is impossible to accurately describe a book in only one or two sentences. As one reads science fiction and fantasy novels set in Texas, certain themes repeat themselves. There are, of course, numerous works about ghosts, vampires, and werewolves. Authors often write about invasions of the state, not only by creatures from outer space, but also by foreigners, including the Russians, the Germans, the Mexicans, the Japanese and even the Israelis. One encounters familiar plot devices, such as time travel, in other books. Stories often depict a Texas devastated by some apocalypse – sometimes it is global warming, sometimes World War III has been fought, and usually lost, by the United States, and, in one case, the disaster consisted of a series of massive earthquakes which created ecological havoc and destroyed most of the region's infrastructure. The mystique of the old west has long been an alluring subject for authors; even Jules Verne and Bram Stoker used Texans in stories. -

Readercon 20 Program Guide

readercon 20 KRW ©2009 program guide The conference on imaginative literature, twentieth edition readercon 20 The Boston Marriott Burlington Burlington, Massachusetts 9th–12th July 2009 Guests of Honor: Elizabeth Hand Greer Gilman Memorial Guest of Honor: Hope Mirrlees program guide Policies and Practical Information........................................................................1 Bookshop Dealers ...................................................................................................4 Readercon 20 Guest Index .....................................................................................5 Readercon 20 Program ...........................................................................................7 Thursday ...........................................................................................................7 Friday ................................................................................................................9 Saturday ..........................................................................................................20 Sunday.............................................................................................................27 Readercon 20 Committee .....................................................................................34 Readercon 21 Advertisement...............................................................................35 Program Participant Bios ....................................................................................37 Hotel Map.....................................................................Just -

Counterfactual Historical Fiction and Possible Worlds Theory

Alternative realities: Counterfactual historical fiction and possible worlds theory RAGHUNATH, Riyukta Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19154/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version RAGHUNATH, Riyukta (2017). Alternative realities: Counterfactual historical fiction and possible worlds theory. Doctoral, Sheffield Hallam University. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Alternative Realities: Counterfactual Historical Fiction and Possible Worlds Theory Riyukta Raghunath A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 Abstract The primary aim of my thesis is to offer a cognitive-narratological methodology with which to analyse counterfactual historical fiction. Counterfactual historical fiction is a genre that creates fictional worlds whose histories run contrary to the history of the actual world. I argue that Possible Worlds Theory is a suitable methodology with which to analyse this type of fiction because it is an ontologically centred theory that can be used to divide the worlds of a text into its various ontological domains and also explain their relation to the actual world. Ryan (1991) offers the most appropriate Possible Worlds framework with which to analyse any fiction. However, in its current form the theory does not sufficiently address the role of readers in its analysis of fiction. Given the close relationship between the actual world and the counterfactual world created by counterfactual historical fiction, I argue that a model to analyse such texts must go beyond categorising the worlds of texts by also theorising what readers do when they read this type of fiction. -

No. 19-1410 in the UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS for THE

USCA4 Appeal: 19-1410 Doc: 15-1 Filed: 05/28/2019 Pg: 1 of 268 No. 19-1410 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT RICHARD ROE, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE, et al., Defendants-Appellants. On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia JOINT APPENDIX VOLUME 1 OF 5 GEOFFREY P. EATON JOSEPH H. HUNT JOHN H. HARDING Assistant Attorney General LAUREN GAILEY G. ZACHARY TERWILLIGER LAURA COOLEY United States Attorney Winston & Strawn LLP 1700 K St. NW MARK B. STERN Washington, DC 20006 MARLEIGH D. DOVER LEWIS S. YELIN SCOTT SCHOETTES JAMES Y. XI Lambda Legal Defense and Attorneys, Appellate Staff Education Fund Civil Division, Room 7515 105 W. Adams St., Suite 2600 U.S. Department of Justice Chicago, IL 60603 950 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20530 PETER E. PERKOWSKI OUTSERVE-SLDN, Inc. P.O. Box 65301 Washington, DC 20035 USCA4 Appeal: 19-1410 Doc: 15-1 Filed: 05/28/2019 Pg: 2 of 268 ANDREW R. SOMMER Greenberg Traurig LLP 1750 Tysons Blvd., Suite 1000 McLean, VA 22102 USCA4 Appeal: 19-1410 Doc: 15-1 Filed: 05/28/2019 Pg: 3 of 268 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 of 5 Docket Entries ..................................................................................................................... JA 1 Complaint (Dec. 19, 2018) ............................................................................................... JA 16 DoDI 1332.18 (Aug. 5, 2014) (Disability Evaluation System) ................................... JA 50 DoDI 1332.45 (July 30, 2018) (Retention Determinations for Non-Deployable Service Members) ................................................................................................JA 108 DoDI 6485.01 (June 7, 2013) (HIV in Military Service Members) ......................... JA 128 DoDI 6490.07 (February 5, 2010) (Deployment-Limiting Medical Conditions for Service Members and DoD Civilian Employees) ................................... -

Geographies of Science Fiction

LOST IN SPACE This page intentionally left blank LOST IN SPACE GEOGRAPHIES OF SCIENCE FICTION EDITED BY ROB KITCHIN AND JAMES KNEALE continuum LONDON • NEW YORK Continuum The Tower Building, 11 York Road, London, SE1 7NX 370 Lexington Avenue, New York, NY 10017-6503 First published 2002 Rob Kitchin, James Kneale and the contributors 2002 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0-8264-5730-4 (hardback) 0-8264-5731-2 (paperback) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lost in space: geographies of science fiction / edited by Rob Kitchin and James Kneale. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8264-5730-4—ISBN 0-8264-5731-2 (pbk. ) 1. Science fiction—History and criticism. 2. Space and time in literatur I. Kitchin, Rob. II. Kneale, James. PN3433. 6. L672001 809. 3'8762'09384—dc21 2001032309 Typeset by Refinecatch Ltd, Bungay, Suffolk Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Cromwell Press, Trowbridge, Wilts CONTENTS Contributors vii Acknowledgements X Foreword xi Michael Marshall Smith 1 Lost in space 1 James Kneale and Rob Kitchin 2 The way it wasn't: alternative histories, contingent geographies 17 Barney Warf 3 Geography's conquest of history in The Diamond Age 39 Michael Longan and Tim Oakes 4 Space, technology and Neal Stephensbn's science fiction 57 Michelle Kendrick 5 Geographies of power and social relations in Marge Piercy's He, She and It 74 Barbara J. -

UF 318 Index Samuel Proctor Family History and Heritage. Life in St

UF 318 Index Samuel Proctor Family history and heritage. Life in St. Augustine. Encounter with President Warren G. Harding. Life in Jacksonville. Early school life. Depression decade, first job, and night school. Relationship with grandparents. Speaking Yiddish and celebrating Jewish heritage. Close, large family unit. Mother’s and grandmother’s cooking. Relationship with brothers and age order. Growing up in Jacksonville: Jewish community, recreational activities, Depression years, growth of Jacksonville, segregation, before air conditioning, Jewish education and interest in history, movies and radio, graduation from high school. University of Florida (UF): cost, NYA (National Youth Administration) job, student population, University College, campus involvement, Gainesville, room and board, choosing a specialization, football, build up to WWII and compulsory ROTC, hitchhiking to Jacksonville. Pearl Harbor. Registering for draft. Master’s degree and thesis. 36th Street Army Depot Project. Military service: Camp Blanding and Camp Shelby, end of WWII. Teaching at UF. Growth of UF. Marriage. Earning Ph.D and writing a dissertation. History of University of Florida 1853 to 1906: East Florida Seminary, Florida Agricultural College, Buckman Act, creating Gainesville campus. Napoleon Bonaparte Broward book. Changing date on University of Florida seal. Activities on campus. Personal life: meeting and marrying Bessie, kids, building their house. Jewish Community in Gainesville: Hillel development, personal involvement. Florida Historical Society. -

Boskone 29 a Convention Report by Evelyn C

Boskone 29 A convention report by Evelyn C. Leeper Copyright 1992 by Evelyn C. Leeper Table of Contents: l Hotels l Dealers Rooms l Art Show l Film Program l Programming l The First Night l Guest of Honor Speech l 1991: The Year in SF on Film and TV l Meeting of the Society for the Aesthetic Rearrangement of History l Hugoes for Electronic Fanac? l 1991: The Year in Review -- Nominating for the Hugos l Turning Points in History: The Weak Spots Where Fiction Can Slip In l The Star Trek Movies: A Look Back l Miscellaneous Traffic was very light most of the way (it got bad only between Hartford and Bradley Airport) and we managed to make the trip to Springfield in just over four and a half hours. Next year, if course, it will take longer to get to Boskone, since it's moving to Framingham. But more on that later. Last year panelists registered in the regular registration area and were given their panelist information there. This year we had to go to the Green Room to get our panelist information. Since one was in the Sheraton and one in the Marriott, this was a trifle inconvenient, but at least we ended up in the hotel with the dealers room. Hotels This year the weather was warmer than usual, making the outdoor run across the street between the Sheraton and the Marriott not too bad, except for Saturday night, when it was raining. The connecting overpass was kept open (it usually closes when all the stores in Baystate West do), but it does add quite a ways onto the distance.