{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 153 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 6, 2007 No. 22 House of Representatives The House met at 10:30 a.m. and was become true. It is Orwellian double- committee of initial referral has a called to order by the Speaker pro tem- think, an amazing concept. statement that the proposition con- pore (Mr. JOHNSON of Georgia). They believe that if you simply just tains no congressional earmarks. So f say you are lowering drug prices, poof, the chairman of the Appropriations it’s done, ignoring the reality that Committee, Mr. OBEY, conveniently DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO prices really won’t be lowered and submitted to the record on January 29 TEMPORE fewer drugs will be made available to that prior to the omnibus bill being The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- our seniors. considered, quote, ‘‘does not contain fore the House the following commu- They believe that if you just say you any congressional earmarks, limited nication from the Speaker: are implementing all of the 9/11 Com- tax benefits, or limited tariff benefits.’’ WASHINGTON, DC, mission’s recommendations, it changes But, in fact, Mr. Speaker, this omnibus February 6, 2007. the fact that the bill that was passed spending bill that the Democrats I hereby appoint the Honorable HENRY C. here on the floor doesn’t reflect the to- passed last week contained hundreds of ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, Jr. to act as Speaker pro tality of those recommendations. -

House Section

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, JUNE 21, 2005 No. 83 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was I would like to read an e-mail that there has never been a worse time for called to order by the Speaker pro tem- one of my staffers received at the end Congress to be part of a campaign pore (Miss MCMORRIS). of last week from a friend of hers cur- against public broadcasting. We formed f rently serving in Iraq. The soldier says: the Public Broadcasting Caucus 5 years ‘‘I know there are growing doubts, ago here on Capitol Hill to help pro- DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO questions and concerns by many re- mote the exchange of ideas sur- TEMPORE garding our presence here and how long rounding public broadcasting, to help The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- we should stay. For what it is worth, equip staff and Members of Congress to fore the House the following commu- the attachment hopefully tells you deal with the issues that surround that nication from the Speaker: why we are trying to make a positive important service. difference in this country’s future.’’ There are complexities in areas of le- WASHINGTON, DC, This is the attachment, Madam June 21, 2005. gitimate disagreement and technical I hereby appoint the Honorable CATHY Speaker, and a picture truly is worth matters, make no mistake about it, MCMORRIS to act as Speaker pro tempore on 1,000 words. -

UUAA Veterans for Peace Annual Report 2020-2021 Group Leader: Michael Muha

UUAA Veterans for Peace Annual Report 2020-2021 Group Leader: Michael Muha UUAA Veterans for Peace is part of a larger organization, Veterans for Peace, which is a global organization of Military Veterans and allies whose collective efforts are to build a culture of peace by using our experiences and lifting our voices. We inform the public of the true causes of war and the enormous costs of wars (including physical, psychological, emotional, environmental), with an obligation to heal the wounds of wars. Our network is comprised of over 140 chapters worldwide whose work includes: educating the public, advocating for a dismantling of the war economy, providing services that assist veterans and victims of war, and most significantly, working to end all wars. We didn’t do what we anticipated because of not having the usual social contact. Along with our parent organization, Veterans for Peace Chapter 93, accomplished the following: • Martin Luther King Day presentations EMU, UM, and Ann Arbor Public Library, with the theme “Beyond Militarism: Where Do We Go From Here?” (https://aadl.org/node/575155) • Ann Arbor’s Veterans Park on Veterans Day, and Detroit’s Grand Circus Park on July 4, erected a memorial for military members from Michigan killed in Iraq and Afghanistan - to remind people of the costs of war • Awarded scholarships to student who will pursue studies in a Peace Studies program or other program that actively promotes the study of global conflict resolution or issues of peace and justice. • To fund our scholarships, hosted a virtual John Lennon Birthday Concert with local musicians, and created a CD: https://www.vfp93.org/john-lennon-concert-cd We definitely relate to the Sixth Principle: The goal of world community with peace, liberty, and justice for all, as well as the First Principle: The inherent worth and dignity of every person, and the Seventh Principle: Respect for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part. -

VVAW's December 2005 Letter

VIETNAM VETERANS AGAINST THE WAR, INC PO Box 408594, Chicago, IL 60640 - (773) 276-4189 www.vvaw.org [email protected] Dear Friend of Vietnam Veterans Against the War, What a difference a year makes! Not only have the American people turned against the war, but Vietnam Veterans Against the War has been able to make a bigger contribution to changing people’s minds about the war than ever before. At our late October National Meeting, the best attended in many, many years, we resolved to further deepen our participation in the national anti-war movement. We heard local representatives talk about their speaking to high school classes, raising funds for the My Lai Peace Park in Vietnam, representing veterans at local anti-war demonstrations, offering personal support to returning Iraq vets, attending local vigils on the night of the 2000th U.S military death in the Iraq war, and engaging in civil disobedience at the White House. Ray Parrish, our military counselor, regularly makes a real difference in the lives of individual veter- ans and GI’s. Ray tells me that some vets who call him want to deal with their Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder symptoms in a political rather than a clinical setting. One vet he talked to had done two tours in Iraq. After the first tour, John didn’t really want to go back, but he didn’t talk to anyone in the GI counsel- ing movement because he was hearing from military commanders that people who opposed the war didn’t support the troops. He told Ray that, between tours, “he and Johnny Walker became best friends.” John got out of the military after his second tour. -

Dear Peace and Justice Activist, July 22, 1997

Peace and Justice Awardees 1995-2006 1995 Mickey and Olivia Abelson They have worked tirelessly through Cambridge Sane Free and others organizations to promote peace on a global basis. They’re incredible! Olivia is a member of Cambridge Community Cable Television and brings programming for the local community. Rosalie Anders Long time member of Cambridge Peace Action and the National board of Women’s Action of New Dedication for (WAND). Committed to creating a better community locally as well as globally, Rosalie has nurtured a housing coop for more than 10 years and devoted loving energy to creating a sustainable Cambridge. Her commitment to peace issues begin with her neighborhood and extend to the international. Michael Bonislawski I hope that his study of labor history and workers’ struggles of the past will lead to some justice… He’s had a life- long experience as a member of labor unions… During his first years at GE, he unrelentingly held to his principles that all workers deserve a safe work place, respect, and decent wages. His dedication to the labor struggle, personally and academically has lasted a life time, and should be recognized for it. Steve Brion-Meisels As a national and State Board member (currently national co-chair) of Peace Action, Steven has devoted his extraordinary ability to lead, design strategies to advance programs using his mediation skills in helping solve problems… Within his neighborhood and for every school in the city, Steven has left his handiwork in the form of peaceable classrooms, middle school mediation programs, commitment to conflict resolution and the ripping effects of boundless caring. -

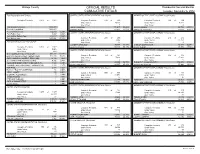

Official Results Cumulative Totals

Orange County OFFICIAL RESULTS Presidential General Election CUMULATIVE TOTALS Tuesday, November 6, 2012 Total Registration and Turnout UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 45th District MEMBER OF THE STATE ASSEMBLY 55th District Complete Precincts: 1,977 of 1,977 Complete Precincts: 519 of 519 Complete Precincts: 160 of 160 Under Votes: 19,555 Under Votes: 8,377 Over Votes: 7 Over Votes: 4 Total Registered Voters 1,683,001 JOHN CAMPBELL 171,417 58.46% CURT HAGMAN 56,736 65.39% Precinct Registration 1,683,001 SUKHEE KANG 121,814 41.54% GREGG D. FRITCHLE 30,033 34.61% Precinct Ballots Cast 552,018 32.80% UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 46th District MEMBER OF THE STATE ASSEMBLY 65th District Early Ballots Cast 5,343 0.32% Vote-by-Mail Ballots Cast 575,843 34.22% Total Ballots Cast 1,133,204 67.33% Complete Precincts: 290 of 290 Complete Precincts: 276 of 276 Under Votes: 7,682 Under Votes: 11,167 PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT Over Votes: 17 Over Votes: 8 LORETTA SANCHEZ 95,694 63.87% SHARON QUIRK-SILVA 68,988 52.04% Complete Precincts: 1,977 of 1,977 JERRY HAYDEN 54,121 36.13% CHRIS NORBY 63,576 47.96% Under Votes: 9,926 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 47th District MEMBER OF THE STATE ASSEMBLY 68th District Over Votes: 614 MITT ROMNEY PAUL RYAN (REP) 582,332 51.87% BARACK OBAMA JOSEPH BIDEN (DEM) 512,440 45.65% Complete Precincts: 184 of 184 Complete Precincts: 345 of 345 7,648 17,944 GARY JOHNSON JAMES P. GRAY (LIB) 14,132 1.26% Under Votes: Under Votes: 5 6 JILL STEIN CHERI HONKALA (GRN) 4,792 0.43% Over Votes: Over Votes: 49,599 54.72% 104,706 60.82% ROSEANNE BARR CINDY SHEEHAN (P-F) 3,348 0.30% GARY DELONG DONALD P. -

Voices of Conscience: Antiwar Opposition in the Military

Voices of Conscience: Antiwar Opposition in the Military Photo: Paul Richards (Estuary Press) May 22-24, 2018 Welcome Welcome to the “Voices of Conscience” conference, the first major academic conference ever held on military antiwar movements. Never before have scholarly and activist communities come together at a major academic institution to probe the impact of soldier and veterans’ antiwar movements and their importance for the strategy of peace. This gathering is historic in another sense. It takes place 50 years after the Vietnam War, a war in which many of us fought and resisted, and 15 years since the invasion of Iraq when others of us spoke out for peace. We gather as the United States continues an endless “war on terror,” conducting combat support operations in 14 countries and launching air strikes in seven, all without constitutional authority and with few citizens aware or concerned. We will address many vital questions during this conference. What was the role of the GI and veterans’ movement in helping bring an end to the U.S. war in Vietnam? How did the collapse of the armed forces affect the Pentagon’s ability to continue waging war? What was the relationship between the military and civilian antiwar movements? How was the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq affected by antiwar opposition? How did dissent within the ranks affect public opinion on ending the war in Vietnam? What can veterans and military service members do today to counter militarism and war and build support for peace? The historic campaigns we examine in this conference are linked to the movements of today, especially to the students and community activists organizing against the scourge of gun violence in our schools and on our streets, just as we march to prevent war and armed violence abroad. -

Maternal Activism

1 Biography as Philosophy The Power of Personal Example for Transformative Theory As I have written this book, my kids have always been present in some way. Sometimes, they are literally present because they are beside me playing, asking questions, wanting my attention. Other times, they are present in the background of my consciousness because I’m thinking about the world they live in and the kind of world I want them to live in. Our life together is probably familiar to many U.S. middle-class women: I work full-time, the kids go to school full time, and our evenings and weekends are filled with a range of activities with which we are each involved. We stay busy with our individual activities, but we also come together for dinner most nights, we go on family outings, and we enjoy our time together. As much time as I do spend with my kids, I constantly feel guilty for not doing enough with them since I also spend significant time preparing for classes, grading, researching, and writing while I’m with them. Along with many other women, I feel the pressure of trying and failing to balance mothering and a career. Although I feel as though I could be a better mother and a bet- ter academic, I also have to concede that I lead a privileged life as a woman and mother. Mothers around the world would love to have the luxury of providing for their children’s physical and mental well-being. In the Ivory Coast and Ghana, children are used as slave labor to harvest cocoa beans for chocolate (Bitter Truth; “FLA Highlights”; Hawksley; The Food Empowerment Project). -

FOR a FUTURE of Peketjiktice

WDMENS ENCAMPMENT FOR A FUTURE OF PEKEtJIKTICE SUMMER 1983'SENECA ARM/ DEPOTS 1590 WOMEN OF THE H0TINONSIONNE IROaiMS CONFEDERACY GATHER AT SENECA TO DEMAND AN END TO MMR AMONG THE NATIONS X 1800s A&0LITI0NIST5 M4KE SENECA COUNTY A MAJOR STOP ON THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD HITO HARRIET TUBMAW HOUSE NEAR THE PRESENT DAI ARMV DEPOTS EARL/ FEMINISTS HOLD FIRST WDMENS RIQHTS CONVENTION AT SENEGA FALLS ID CALL FOR SUFFRAGE & EQUAL MPTICJMTION IN ALL OTHEP AREAS OF LIFE ' TOD/W URBAN & RURA. WOMEN JOIN TOGETHER IN SENECA G0UNI7 TO CHALLENGE "ME NUCLEAR THREAT TO UFE ITSELF^ WE FOCUS ON THE WEAPONS AT 1UE SENECA ARMY DEPOT TO PREVENT DEPU)yMENT OF NATO MISSILES IN SOUDARITY WITH THE EUPOPE/W PEACE MO^MENT^ RESOURCE HANDBOOK Introduction The idea of a Women's Peace Camp in this country in solidarity with the Peace Camp movement in Europe and the Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp, in particular, was born at a Conference on Global Feminism and Disarmament on June 11, 1982. The organizing process began with discussions between Women's International League for Peace and Freedom and women in the Upstate Feminist Peace Alliance (NY), to consider siting the camp at the Seneca Army Depot in Romulus, NY. The planning meetings for the Encampment have since grown to include women from Toronto, Ottawa, Rochester, Oswego, Syracuse, Geneva, Ithaca, Albany, New York City, Boston, Philadelphia, and some of the smaller towns in between. Some of the tasks have been organized regionally and others have been done locally. Our planning meetings are open, and we are committed to consensus as our decision making process. -

Speaking from the Heart: Mediation and Sincerity in U.S. Political Speech

Speaking from the Heart: Mediation and Sincerity in U.S. Political Speech David Supp-Montgomerie A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication Studies in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Christian Lundberg V. William Balthrop Carole Blair Lawrence Grossberg William Keith © 2013 David Supp-Montgomerie ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT David Supp-Montgomerie: Speaking from the Heart: Mediation and Sincerity in U.S. Political Speech (Under the direction of Christian Lundberg) This dissertation is a critique of the idea that the artifice of public speech is a problem to be solved. This idea is shown to entail the privilege attributed to purportedly direct or unmediated speech in U.S. public culture. I propose that we attend to the ēthos producing effects of rhetorical concealment by asserting that all public speech is constituted through rhetorical artifice. Wherever an alternative to rhetoric is offered, one finds a rhetoric of non-rhetoric at work. A primary strategy in such rhetoric is the performance of sincerity. In this dissertation, I analyze the function of sincerity in contexts of public deliberation. I seek to show how claims to sincerity are strategic, demonstrate how claims that a speaker employs artifice have been employed to imply a lack of sincerity, and disabuse communication, rhetoric, and deliberative theory of the notion that sincere expression occurs without technology. In Chapter Two I begin with the original problem of artifice for rhetoric in classical Athens in the writings of Plato and Isocrates. -

Written Evidence Submitted by the Veterans for Peace UK (INR0067)

Written evidence submitted by the Veterans for Peace UK (INR0067) Introduction to Veterans for Peace UK Veterans for Peace UK (VFP UK) was founded in London in 2011. Veterans For Peace UK is a voluntary and politically independent ex-services organisation of men and women who have served in conflicts from World War 2 through to Afghanistan. As a result of our collective experiences we firmly believe that “War is not the solution to the problems we face in the 21st century”. We are not a pacifist organisation; we accept the inherent right of self-defence in response to an armed attack. We work to influence the foreign and defence policy of the UK, for the larger purpose of world peace. Summary Given that many of the institutions, legal frameworks and skills necessary to increase international understanding and facilitate global co-operation are already in place, our submission focuses on some foreign policy areas where we believe that more effective use could be made of these existing tools. It is vital to strengthen such resources if we are to achieve peaceful co-existence. The starting point for this Review must be a careful re- evaluation of what is needed to provide genuine and sustainable security. The following are our responses to some of the questions listed in your call for evidence. THE PROCESS OF THE INTEGRATED REVIEW The efficacy of the Review’s process 1. ‘What is Security?’ At present there is no established or agreed answer across government departments and policy makers. What does the state want to ‘secure’? From what, from whom and who for? Once these questions are answered we can then determine how we use our resources: human, industrial, technological, financial, to achieve a secure future and incorporate them into developing FCO priorities. -

The War Divides America

hsus_te_ch16_s03_s.fm Page 656 Friday, January 16, 2009 8:33 PM ᮤ A Vietnam veteran protests the war in 1970. WITNESS HISTORY AUDIO Step-by-Step The “Living-Room War” SECTION Instruction Walter Cronkite, the anchor of the CBS Evening News, 3 was the most respected television journalist of the 1960s. His many reports on the Vietnam War were SECTION 3 models of balanced journalism and inspired the Objectives confidence of viewers across the United States. But during the Tet Offensive, Cronkite was shocked by the As you teach this section, keep students disconnect between Johnson’s optimistic statements focused on the following objectives to help and the gritty reality of the fighting. After visiting them answer the Section Focus Question and Vietnam in February of 1968, he told his viewers: master core content. “We have been too often disappointed by the • Describe the divisions within American optimism of the American leaders, both in Vietnam society over the Vietnam War. and Washington, to have faith any longer in the silverlinings they find in the darkest clouds.... [I]t • Analyze the Tet Offensive and the seems now more certain than ever that the bloody American reaction to it. experience of Vietnam is to end in stalemate.” • Summarize the factors that influenced the —Walter Cronkite, 1968 outcome of the 1968 presidential election. ᮡ Walter Cronkite The War Divides America Prepare to Read Objectives Why It Matters President Johnson sent more American troops • Describe the divisions within American society to Vietnam in order to win the war. But with each passing year, over the Vietnam War.