Tapping Our Potential: Diaspora Communities and Canadian Foreign Policy Is a Joint Initiative of the Following Two Organizations, Both Based in Toronto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major Research Paper

MAJOR RESEARCH PAPER IDENTITIES AND EXPERIENCES OF BLACK-AFRICAN IMMIGRANT YOUTH IN CANADA Submitted by: Fenan Kalaty Honours, BA with Specialization in Psychology (2010) Supervisor: Natacha Gagné Committee Member: Philippe Couton Date: February 2013 Master of Arts in Sociology University of Ottawa Department of Sociology and Anthropology Thank you to my parents, their love and support made this major research paper possible. Thank you to my siblings, my built-in best friends. 2 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………….5 A Reflexive Note……………………………………………………………………………..5 African Immigrants in Canada………………………………………………………………..9 Research Question…………………………………………………………………………..11 The Challenges in Defining “African-Canadian”……………………………………...........12 Conceptual Tools…………………………………………………………………...17 Youth………………………………………………………………………………………..17 Immigration and Acculturation……………………………………………………………...18 Identity…………………………………………………………………………………........20 Biculturalism………………………………………………………………………………...21 Ethnicity, Ethnic Groups, and Ethnic Identities……………………………………….........24 Methodology………………………………………………………………………..28 Method…………………………………………………………………………………........28 Sample………………………………………………………………………………………29 Literature Review…………………………………………………………………..34 Identifying with Multiple Travels…………………………………………………………...34 The Significance of Loss……………………………………………………………………34 Place Identity………………………………………………………………………………..35 The Third Space……………………………………………………………………………..37 “Black” and Hip-Hop Identity……………………………………………………………....43 “Black” and Gendered -

Eritrean Canadians Protest Eritrean Consulate Fundraising Event

Eritrean Canadians Protest Eritrean consulate fundraising event Eritrean Canadians Protest Eritrean consulate fundraising event By Aaron Berhane The Eritrean Human Rights Group staged a popular demonstration against an Eritrean consulate-sponsored fundraising event at Sheraton Hotel in downtown Toronto on August 5. The protesters disclosed the hidden agenda of the so-called “community” event by chanting such slogans as: “No Fundraising to finance terrorists”; “No fundraising to finance the dictator”; “Stop soliciting our churches; “Stop the 2% extortion tax; “Shame on Sheraton Hotel for hosting a terrorist fundraising event”; and “Close the Eritrean consulate”. The Eritrean human rights activists attracted the attention of many pedestrians. They distributed literature that disclosed the dictatorial nature of the Eritrean regime, and increased awareness the illegal activities of the Eritrean Consulate in raising funds and extorting Eritrean Canadians to pay the notorious 2% tax. The protest conveyed a strong message and drew the attention of the hotel guests. One of the guests arrived by taxi and saw the protesters and read the picket signs. He happened to be familiar with the Afewerki regime, and said, “‘I am going to cancel my reservation right now and book in another hotel as a support to your cause”. There were also several taxis that stopped with their guests at the gate and left the premise instantly when they saw the protesters. The Eritrean consulate in Toronto rented a hall at Sheraton Hotel in the name of two agents of the consulate who work in the hotel. They hid their politically motivated event to raise funds for the military activities of the Eritrean dictator and to finance terrorist groups in the horn of Africa. -

Rethinking the Canadian Diaspora by Kenny Zhang* Executive Summary

September 2007 www.asiapacifi c.ca Number 46 “Mission Invisible” – Rethinking the Canadian Diaspora By Kenny Zhang* Executive Summary The evacuation of tens of thousands of Canadians Th e size of the Canadian diaspora is remarkable from Lebanon in 2006, a pending review of dual relative to the resident national population, even when citizenship and a formal diplomatic protest to compared with other countries that are well-known China over the jailing of a Canadian citizen for for their widely dispersed overseas communities. Th e alleged terrorist activities are examples of the new survey shows that the Canadian diaspora does complex and extensive range of policy issues raised not exist as scattered individuals, but as an interactive by the growing number of Canadian citizens living community with various organizations associated abroad. It has also shown the need for Canada to with Canada. Th e study also suggests that living think strategically about the issue of the Canadian abroad does not make the Canadian diaspora less diaspora, rather than deal with the problems raised “Canadian,” although it is a heterogeneous group. Th e on a case-by-case basis. majority of overseas Canadians still call Canada home and have a desire to return to Canada. Many keep An earlier report (Commentary No. 41) by the close ties with the country by working for a Canadian Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada (APF Canada) entity and visiting families, friends, business clients or discussed the concept of the Canadian diaspora partners, and various other counterparts in Canada. and estimated the size of this community at 2.7 million. -

A Stone in the Water

A STONE IN THE WATER Report of the Roundtables with Afghan-Canadian Women On the Question of the Application UN Security Council Resolution 1325 in Afghanistan July 2002 Organized by the The Honourable Mobina S.B. Jaffer of the Advocacy Subcommittee of the Canadian Committee on Women, Peace and Security in partnership with the YWCA of Canada With Financial Support from the Human Security Program of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, Canada We acknowledge The Aga Khan Council for Ontario for their support in this initiative 0 Speechless At home, I speak the language of the gender that is better than me. In the mosque, I speak the language of the nation that is better than me. Outside, I speak the language of those who are the better race. I am a non-Arabic Muslim woman who lives in a Western country. Fatema, poet, Toronto 1 Dedication This report is dedicated to the women and girls living in Afghanistan, and the future which can be theirs 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY…………………………………………………………insert BACKGROUND……………………………………………………………………...….4 OBJECTIVES……...………………………………………………………………….…9 REPORT………………………………………………………………………………...11 Introduction………………………………………………………………………11 What Are The Barriers to the Full Participation of Women in Afghan Society (Question 1)…………………………………….……………13 Personal Safety and Security…………………………………………………….13 Warlords…………………………………………………………………14 Lack of Civilian Police Force and Army………………………………...15 Justice and Accountability……………………………………………………….16 Education……………………………………………………………………..….18 -

The Evolution of the Franco-American Novel of New England (1875-2004)

BORDER SPACES AND LA SURVIVANCE: THE EVOLUTION OF THE FRANCO-AMERICAN NOVEL OF NEW ENGLAND (1875-2004) By CYNTHIA C. LEES A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2006 Copyright 2006 By Cynthia C. Lees ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the members of my supervisory committee, five professors who have contributed unfailingly helpful suggestions during the writing process. I consider myself fortunate to have had the expert guidance of professors Hélène Blondeau, William Calin, David Leverenz, and Jane Moss. Most of all, I am grateful to Dr. Carol J. Murphy, chair of the committee, for her concise editing, insightful comments, and encouragement throughout the project. Also, I wish to recognize the invaluable contributions of Robert Perreault, author, historian, and Franco- American, a scholar who lives his heritage proudly. I am especially indebted to my husband Daniel for his patience and kindness during the past year. His belief in me never wavered. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................ iii LIST OF FIGURES .................................................... vii ABSTRACT.......................................................... viii CHAPTER 1 SITING THE FRANCO-AMERICAN NOVEL . 1 1.1 Brief Overview of the Franco-American Novel of New England . 1 1.2 The Franco-American Novel and the Ideology of La Survivance ..........7 1.3 Framing the Ideology of La Survivance: Theoretical Approaches to Space and Place ....................................................13 1.4 Coming to Terms with Space and Place . 15 1.4.1 The Franco-American Novel and the Notion of Place . -

On Multiculturalism's Margins: Oral History and Afghan Former

On Multiculturalism’s Margins: Oral History and Afghan Former Refugees in Early Twenty-first Century Winnipeg By Allison L. Penner A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of History Joint Master’s Program University of Manitoba / University of Winnipeg Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright © 2019 by Allison L. Penner Abstract Oral historians have long claimed that oral history enables people to present their experiences in an authentic way, lauding the potential of oral history to ‘democratize history’ and assist interviewees, particularly those who are marginalized, to ‘find their voices’. However, stories not only look backward at the past but also locate the individual in the present. As first demonstrated by Edward Said in Orientalism, Western societies have a long history of Othering non-Western cultures and people. While significant scholarly attention has been paid to this Othering, the responses of orientalised individuals (particularly those living in the West) have received substantially less attention. This thesis focuses on the multi-sessional life story oral history interviews that I conducted with five Afghan-Canadians between 2012 and 2015, most of whom came to Canada as refugees. These interviews were conducted during the Harper era, when celebrated Canadian notions of multiculturalism, freedom, and equality existed alongside Orientalist discourses about immigrants, refugees, Muslims, and Afghans. News stories and government policies and legislation highlighted the dangers that these groups posed to the Canadian public, ‘Canadian’ values, and women. Drawing on the theoretical work of notable oral historians including Mary Chamberlain and Alessandro Portelli, I consider the ways in which the narrators talked about themselves and their lives in light of these discourses. -

Canadians Abroad V3:Layout 1

CANADA’S GLOBAL ASSET Canadians abroad are a major asset for Canada’s international affairs. How can we deepen our connections with citizens overseas for the benefit of all Canadians? ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada initiated the Canadians Abroad Project as part of a policy research consortium and is deeply grateful to its project supporters—the Royal Bank of Canada Foundation, Citizenship and Immigration Canada, the Government of British Columbia, the Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation, and Western Economic Diversification—for their generous investment of time and money. More than just a research report, the findings of this project provide a platform for policy development and public awareness about Canadians abroad, and an opportunity to tap into Canada’s global asset. Don DeVoretz, Research Director Kenny Zhang, Senior Project Manager Copyright 2011, by Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada All rights reserved. Canadians Abroad: Canada’s Global Asset may be excerpted or reproduced only with the written permission of the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. For further information, please contact Kenny Zhang: Tel: 1.604.630.1527 Fax: 1.604.681.1370 Email: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 CHAPTER 1: Demographics of Canadians Abroad 8 CHAPTER 2: Emigrant Attachments to Canada 16 CHAPTER 3: Citizenship Issues for Canadians Abroad 26 CHAPTER 4: Safety and Consular Services 34 CHAPTER 5: Economics of Emigration: Taxation and Economic Performance of Returnees 42 CHAPTER 6: Views of Canadians at Home and Abroad 50 CHAPTER 7: Policy Responses: An Agenda for Action and Further Research 54 APPENDICES 58 REFERENCES 60 PAGE 2 FOREWORD In the same way that globalization has connected distant corners of Canadians who choose to live overseas as “disloyal”. -

Coercive Transnational Governance and Its Impact on the Settlement Process of Eritrean Refugees in Canada Aaron Berhane and Vappu Tyyskä

Document generated on 09/25/2021 5:19 a.m. Refuge Canada's Journal on Refugees Revue canadienne sur les réfugiés Coercive Transnational Governance and Its Impact on the Settlement Process of Eritrean Refugees in Canada Aaron Berhane and Vappu Tyyskä Volume 33, Number 2, 2017 Article abstract This article will examine the transnational practices of the Eritrean URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1043065ar government, and their impact on the settlement of Eritrean refugees in DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1043065ar Canada. The focus is on actions by the Eritrean regime that have a negative effect on refugees’ capacities for successful integration, and undermine See table of contents Canadian sovereignty. The concept of coercive transnational governance (CTG) is introduced, to highlight this neglected aspect of refugee resettlement, with illustrations from 11 interviews, including eight Eritrean refugees, one Publisher(s) Eritrean community activist, and two Canadian law enforcement officers, about the impact of CTG on Eritrean refugees’ lives. Centre for Refugee Studies, York University ISSN 0229-5113 (print) 1920-7336 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Berhane, A. & Tyyskä, V. (2017). Coercive Transnational Governance and Its Impact on the Settlement Process of Eritrean Refugees in Canada. Refuge, 33(2), 78–87. https://doi.org/10.7202/1043065ar Copyright (c), 2017 Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

In a Constant State of Flux: the Cultural Hybrid Identities of Second-Generation Afghan-Canadian Women

IN A CONSTANT STATE OF FLUX: THE CULTURAL HYBRID IDENTITIES OF SECOND-GENERATION AFGHAN-CANADIAN WOMEN By: Saher Malik Ahmed, B. A A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Post-Doctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Women’s and Gender Studies Pauline Jewett Institute of Women’s and Gender Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario July 2016 © 2016 Saher Malik Ahmed Abstract This study, guided by feminist methodology and cultural hybrid theory, explores the experiences of Afghan-Canadian women in Ottawa, Ontario who identify as second- generation. A qualitative approach using in-depth interviews with ten second-generation Afghan-Canadian women reveals how these women are continuously constructing their hybrid identities through selective acts of cultural negotiation and resistance. This study will examine the transformative and dynamic interplay of balancing two contrasting cultural identities, Afghan and Canadian. The findings will reveal new meanings within the Afghan diaspora surrounding Afghan women’s gender roles and their strategic integration into Canadian society. i Acknowledgments I am deeply indebted to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Amrita Hari. I thank her sincerely for her endless guidance, patience, and encouragement throughout my graduate studies. I have benefited from her wisdom and insightful feedback that has helped me develop strong research and academic skills, and for this I am immensely grateful. I would like to thank Dr. Karen March, my thesis co-supervisor for her incisive comments and challenging questions. I will never forget the conversation I had with her on the phone during the early stages of my research when she reminded me of the reasons why and for whom this research is intended. -

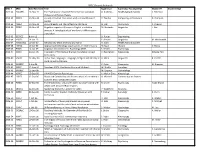

SREC Cleared Protocols

SREC Cleared Protocols SREC # SREC Date Received Title Supervisor Supervisor Faculty/Dept Student PI Student Dept 2012 64 HASSREC 16-Nov-12 The Psychosocial impact of Retirement on Canadian G. Andrews Health,Aging & Society S. Paterson Professional Hockey Players 2012 63 KSREC 16-Nov-12 A study of human interaction with a virtual 3D world R. Teather Computing and Software G. Patriquin builder 2012 65 PSREC 19-Nov-12 Binaural Beats and Their Effects on Vigilance G. Hall Psychology A. Cheung 2012 66 PSREC 19-Nov-12 Cognitive aspects of Korean-to-English translation M. Stroinska Linguistics J. Kim process: A Translog study of word order differences in translation 2013 03 BESREC 8-Jan-13 D. Potter Engineering 2013 04 HSREC 14-Jan-13 E. Service Linguistics M. MacDonald 2009 04 HASGSREC 13-Jan-09 Gerontology 3H03: Diversity and Aging A. Joshi Health,Aging & Society 2009 05 HSREC 13-Jan-09 Appropriate technology organizations in recent history M. Egan History V. Rocca 2009 06 PSREC 14-Jan-09 Cognitive Neuroscience II: Psychology 4BN3 S. Becker Psychology 2006 37 KSREC 20-Apr-06 The realm of HIV/AIDS at the Naz Foundation in New B. Henderson Kinesiology Nitasha Puri Delhi, India 2006 40 HSREC 23-May-06 In Our Own Languages: Language, Religion and Identity in A. Moro Linguistics B. Chettle Local Immigrant Groups 2006 41 GGSREC 5-Jun-06 C. Eyles Geography M. Stoesser 2006 42 SSREC 25-Aug-06 Sociology 3O03: Qualitative Research Methods W. Shaffir Sociology 2006 43 GGSREC 11-Sep-06 M. Grignon Gerontology 2006 44 KSREC 15-Sep-06 KIN 4I03: Exercise Psychology K. -

Identity Formation and Negotiation of Afghan Female Youth . in Ontario

Identity Formation and Negotiation of Afghan Female Youth . in Ontario Tabasum Akseer, B.A. Department of Graduate and Undergraduate Studies in Education . Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Education · Faculty of Education, Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © Tabasum Akseer, 2011 Abstract The following thesis provides an empirical case study in which a group of 6 first generation female Afghan Canadian youth is studied to determine their identity negotiation and development processes in everyday experiences. This process is investigated across different contexts of home, school, and the community. In tenns of schooling experiences, 2 participants each are selected representing public, Islamic, and Catholic schools in Southern Ontario. This study employs feminist research methods and is analyzed through a convergence of critical race theory (critical race feminism), youth development theory, and feminist theory. Participant experiences reveal issues of racism, discrimination, and bias within schooling (public, Catholic) systems. Within these contexts, participants suppress their identities or are exposed to negative experiences based on their ethnic or religious identification. Students in Islamic schools experience support for a more positive ethnic and religious identity. Home and community provided nurturing contexts where participants are able to reaffirm and develop a positive overall identity. 11 Ackilowledgements My Lord, increase me in knowledge (Quran 20:114) This thesis is first and foremost dedicated to my loving parents, Dr. M. Ahmad Akseer and Ambara Akseer. Thank you for your support throughout the years. My achievements are a reflection of the excellent guidance and support I have received from my family. Thank you especially to my eldest sibling Kamilla who has been a role model since the beginning. -

Protestant Christians of the Arabic-Speaking Diaspora and the Presbyterian Church in Canada

Mashriq & Mahjar 4, no. 1 (2017),86-118 ISSN 2169-4435 Peter G. Bush PROTESTANT CHRISTIANS OF THE ARABIC-SPEAKING DIASPORA AND THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH IN CANADA Abstract Arab Protestants are an understudied group in Canada, and this paper seeks to address that gap by describing the religious transnationalism of Arab Protestants in The Presbyterian Church in Canada. The six Arabic-speaking congregations explored have sought to negotiate space for an Arab Protestant identity within a Eura-Canadian denomination. They have done this not by being an enclave separate within the denomination but through engagement with the denomination. In the negotiation process, the Arabic-speaking congregations have been shaped by the Canadian church and the Canadian church has been shaped by the presence of an Arab identity in its midst. Lighthouse Evangelical Arabic Church, Winnipeg, a congregation of The Presbyterian Church in Canada, held its summer conference in August 2015 at the South Beach Resort north of Winnipeg. Outside the meeting room a banner read in English "One Family, Big Vision, Kingdom Focus." While the audience was slow to gather, in the end some eighty adults sat on the 120 chairs set up. The Saturday evening session began with singing and prayer led by a worship leader flown in from the Middle East for the conference. The songs, accompanied by drums, guitar and keyboard, had a distinctive Middle Eastern flavor. Notably, the men along with the women in the audience joined in the singing. Following forty minutes of worship the speaker was introduced. He had come from Kansas City to speak at the gathering.