Henry Spelman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds

Defining the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for The Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds Prepared By: Scott M. Strickland Virginia R. Busby Julia A. King With Contributions From: Francis Gray • Diana Harley • Mervin Savoy • Piscataway Conoy Tribe of Maryland Mark Tayac • Piscataway Indian Nation Joan Watson • Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Subtribes Rico Newman • Barry Wilson • Choptico Band of Piscataway Indians Hope Butler • Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians Prepared For: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, Maryland St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland November 2015 ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this project was to identify and represent the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for the Nanjemoy and Mattawoman creek watersheds on the north shore of the Potomac River in Charles and Prince George’s counties, Maryland. The project was undertaken as an initiative of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay office, which supports and manages the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. One of the goals of the Captain John Smith Trail is to interpret Native life in the Middle Atlantic in the early years of colonization by Europeans. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept, developed as an important tool for identifying Native landscapes, has been incorporated into the Smith Trail’s Comprehensive Management Plan in an effort to identify Native communities along the trail as they existed in the early17th century and as they exist today. Identifying ICLs along the Smith Trail serves land and cultural conservation, education, historic preservation, and economic development goals. Identifying ICLs empowers descendant indigenous communities to participate fully in achieving these goals. -

American Indians of the Chesapeake Bay: an Introduction

AMERICAN INDIANS OF THE CHESAPEAKE BAY: AN INTRODUCTION hen Captain John Smith sailed up the Chesapeake Bay in 1608, American Indians had W already lived in the area for thousands of years. The people lived off the land by harvesting the natural resources the Bay had to offer. In the spring, thousands of shad, herring and rockfish were netted as they entered the Chesapeake’s rivers and streams to spawn. Summer months were spent tending gardens that produced corn, beans and squash. In the fall, nuts such as acorns, chestnuts and walnuts were gathered from the forest floor. Oysters and clams provided another source of food and were easily gathered from the water at low tide. Hunting parties were sent overland in search of deer, bear, wild turkey and other land animals. Nearby marshes provided wild rice and tuckahoe (arrow arum), which produced a potato-like root. With so much food available, the American Indians of the Chesapeake region were able to thrive. Indian towns were found close to the water’s edge near freshwater springs or streams. Homes were made out of bent saplings (young, Captain John Smith and his exploring party encounter two Indian men green trees) that were tied into a spearing fish in the shallows on the lower Eastern Shore. The Indians framework and covered with woven later led Smith to the village of Accomack, where he met with the chief. mats, tree bark, or animal skins. Villages often had many homes clustered together, and some were built within a palisade, a tall wall built with sturdy sticks and covered with bark, for defense. -

The First People of Virginia a Social Studies Resource Unit for K-6 Students

The First People of Virginia A Social Studies Resource Unit for K-6 Students Image: Arrival of Englishmen in Virginia from Thomas Harriot, A Brief and True Report, 1590 Submitted as Partial Requirement for EDUC 405/ CRIN L05 Elementary Social Studies Curriculum and Instruction Professor Gail McEachron Prepared By: Lauren Medina: http://lemedina.wmwikis.net/ Meagan Taylor: http://mltaylor01.wmwikis.net Julia Vans: http://jcvans.wmwikis.net Historical narrative: All group members Lesson One- Map/Globe skills: All group members Lesson Two- Critical Thinking and The Arts: Julia Vans Lesson Three-Civic Engagement: Meagan Taylor Lesson Four-Global Inquiry: Lauren Medina Artifact One: Lauren Medina Artifact Two: Meagan Taylor Artifact Three: Julia Vans Artifact Four: Meagan Taylor Assessments: All group members 2 The First People of Virginia Introduction The history of Native Americans prior to European contact is often ignored in K-6 curriculums, and the narratives transmitted in schools regarding early Native Americans interactions with Europeans are often biased towards a Euro-centric perspective. It is important, however, for students to understand that American History did not begin with European exploration. Rather, European settlement in North America must be contextualized within the framework of the pre-existing Native American civilizations they encountered upon their arrival. Studying Native Americans and their interactions with Europeans and each other prior to 1619 aligns well with National Standards for History as well as Virginia Standards of Learning (SOLs), which dictate that students should gain an understanding of diverse historical origins of the people of Virginia. There are standards in every elementary grade level that are applicable to this topic of study including Virginia SOLs K.1, K.4, 1.7, 1.12, 2.4, 3.3, VS.2d, VS.2e, VS.2f and WHII.4 (see Appendix A). -

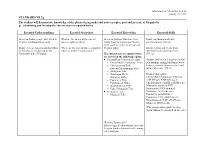

STANDARD VS.2G

Attachment A, Memo No. 014-13 January 18, 2013 STANDARD VS.2g The student will demonstrate knowledge of the physical geography and native peoples, past and present, of Virginia by g) identifying and locating the current state-recognized tribes. Essential Understandings Essential Questions Essential Knowledge Essential Skills American Indian people have lived in What are the names of the current American Indians, who trace their Draw conclusions and make Virginia for thousands of years. state-recognized tribes? family histories back to well before generalizations. (VS.1d) 1607, continue to live in all parts of Today, eleven† American Indian tribes Where are the current state-recognized Virginia today. Interpret ideas and events from in Virginia are recognized by the tribes located in Virginia today? different historical perspectives. Commonwealth of Virginia. The current state-recognized tribes (VS.1g) are located in the following regions: Coastal Plain (Tidewater) region: Analyze and interpret maps to explain – Cheroenhaka (Nottoway) Tribe† relationships among landforms, water – Chickahominy Tribe features, climatic characteristics, and – Eastern Chickahominy Tribe historical events. (VS.1i) – Mattaponi Tribe – Nansemond Tribe Pronunciation guide: – Nottoway Tribe† Cheroenhaka (Nottoway): Chair-oh- – Pamunkey Tribe en-HAH-kah (NAH-toh-way)† – Patawomeck Tribe† Chickahominy: CHICK-a-HOM-a-nee – Rappahannock Tribe Mattaponi: ma-ta-po-NYE – Upper Mattaponi Tribe Nansemond: NAN-sa-mund Piedmont region: Nottoway: NAH-toh-way† – Monacan Tribe Pamunkey: pa-MUN-kee Patawomeck: Pət- OW-ə-meck† Rappahannock: RAP-a-HAN-nock Monacan: MON-a-cun (The pronunciation guide for these words will not be assessed on the test.) †Revised January 2013 These technical edits will not affect the Virginia Studies Standards of Learning test at this time. -

ELECT-643 Voter Identification Chart

Voter Identification All voters casting a ballot in-person will be asked to show one form of identification. Any voter who does not present acceptable photo identification must vote a provisional ballot. Identification Is it accepted? Valid1 photo ID Yes, if issued by an employer; the U.S. or Virginia government; or a school, college, or university located in Virginia Government-issued photo ID card from a federal, VA, or local Yes political subdivision Valid DMV-issued photo ID card Yes Valid Tribal enrollment or other tribal ID Yes, if issued by one of the 11 tribes recognized by VA** Valid U.S. passport or passport card Yes Valid employee ID card issued by voter’s employer in ordinary Yes course of business (public or private employer) Credit card displaying a photograph No Membership card from private organization displaying a photograph No U.S. Military photo ID Yes Photo IDs Nursing home resident photo ID Yes, if issued by government facility Voter photo ID card issued by the Department of Elections Yes Valid student photo ID issued by a public or private school of higher Yes education located in VA Valid student photo ID issued by a public high school in VA Yes Valid student photo ID issued by a private high school in VA Yes Valid Virginia driver’s license or DMV-issued photo ID Yes Valid out-of-state driver’s license No Virginia voter photo identification requirements: Va. Code § 24.2-643(B) Valid Virginia driver's license Valid United States passport Any other photo identification card issued by a government agency of the Commonwealth, one of its political subdivisions, or the United States Valid student identification card containing a photograph of the voter issued by any institution of higher education located in the Commonwealth of Virginia Any valid employee identification card containing a photograph of the voter and issued by an employer of the voter in the ordinary course of the employer's business * “Valid” means the document is genuine, bears the photograph of the voter, and is not expired for more than 12 months. -

Upper Potomac Buoy History

Upper Potomac Buoy History Historians believe that Capt. John Smith and his crew passed by this point in their Discovery Barge twice in June 1608. The first time was on June 22 when they headed upriver as they explored the Potomac and searched in vain for the Northwest Passage through the continent to the Pacific Ocean. Several days before, they had stopped briefly 40 miles downstream on today's Potomac Creek to visit the Patawomeck chief and his people, the farthest-upstream tribe thought to be allies of the paramount chief Powhatan. Scholars reconstructing this part of the expedition believe that the reception the Englishmen received at Patawomeck was chilly, so they crossed the river and followed the Maryland shoreline to the more welcoming Piscataway people at the towns of Nussamek, near today's Mallows Bay, and Pamacocack, just inside the mouth of Mattawoman Creek, where General Smallwood State Park is located now. They also returned to the Virginia side to visit Tauxenent, inside the mouth of today's Occoquan River. The people in the Piscataway communities urged Smith to visit their paramount chief, or tayac, at Moyaons, which is still sacred ground to the Piscataway people today but which also houses the National Colonial Farm (which is open to the public), just below the mouth of Piscataway Creek. The Piscataway tayac welcomed Smith and the crew and feasted them, we believe on the evening of June 21. The next day, well-fed and rested, the English took their Discovery Barge upriver past this point for an overnight visit with the Anacostan people at the town of Nacotchtank, located on the south side of the mouth of the Anacostia River, at the current site of Bolling Air Force Base. -

Voter Identification Card

Voter Identification All voters will be asked to show one form of identification. Any voter who does not have identification required by state or federal law must vote a provisional ballot. Identification Is it accepted? Valid* photo ID Yes, if issued by government, employer, or institute of higher education in VA. Government-issued ID card from federal, VA, or local subdivision Yes (including political subdivisions) DMV-Issued Photo ID Card Yes Tribal enrollment or other tribal ID Yes, if issued by one of 11 tribes recognized by VA.** US Passport or Passport Card Yes Valid* employee ID card issued by voter’s employer in ordinary Yes course of business (public or private employer) Photo IDs Photo Credit card displaying photograph No Membership card from private organization No Military ID Yes Nursing home resident ID Yes, if issued by government facility. Voter Photo Identification Card issued by the Department of Yes Elections Identification Is it accepted? Valid* student ID issued by a public or private school of higher Yes education located in VA displaying photo Valid* student ID issued by a public or private school of higher No education outside of VA displaying photo Student ID issued by a public high school in VA displaying a photo Yes Student IDs Student ID issued by a private high school in VA displaying a photo No Valid* Virginia Driver’s License or DMV-issued Photo ID Yes Virginia Driver’s License that is expired Yes operating state - Valid* out-of-state driver’s license No Driver’s or License non identification Virginia requirements: Va. -

The 1622 Powhatan Uprising and Its Impact on Anglo-Indian Relations

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-15-2016 The 1622 Powhatan Uprising and Its Impact on Anglo-Indian Relations Michael Jude Kramer Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kramer, Michael Jude, "The 1622 Powhatan Uprising and Its Impact on Anglo-Indian Relations" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 513. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/513 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE 1622 POWHATAN UPRISING AND ITS IMPACT ON ANGLO-INDIAN RELATIONS Michael J. Kramer 112 Pages On March 22, 1622, Native Americans under the Powhatan war-leader Opechancanough launched surprise attacks on English settlements in Virginia. The attacks wiped out between one-quarter and one-third of the colony’s European population and hastened the collapse of the Virginia Company of London, a joint stock company to which England’s King James I had granted the right to establish settlements in the New World. Most significantly, the 1622 Powhatan attacks in Virginia marked a critical turning point in Anglo-Indian relations. Following the famous 1614 marriage of the Native American Pocahontas to Virginia colonist John Rolfe and her conversion to Christianity, English colonists in North America and English policymakers in Europe entertained considerable optimism that other Native Americans could be persuaded to embrace both English culture and the Christian faith. -

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 79/Tuesday, April 27, 2021/Notices

22258 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 79 / Tuesday, April 27, 2021 / Notices members of the Pawnee Nation of burials but without any further DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Oklahoma. attributions. Human skeletal remains In 1940, 321 cultural items were and associated funerary objects from National Park Service removed from cemeteries associated this site were repatriated to the Pawnee [NPS–WASO–NAGPRA–NPS0031769; with the Clarks site (25PK1) in Polk Nation of Oklahoma in 1990–1991. The PPWOCRADN0–PCU00RP14.R50000] County, NE. These objects were four unassociated funerary objects are recovered during archeological three soil samples and one flintlock Notice of Inventory Completion: excavations by the Nebraska State rifle. Valentine Museum, Richmond, VA Historical Society. The 321 objects are listed as having been recovered from This village was occupied by the AGENCY: National Park Service, Interior. burials but without any further Kitkahaki Band of the Pawnee from ACTION: Notice. attributions. Human skeletal remains about 1775 to 1809, based on and associated funerary objects from archeological and ethnohistorical SUMMARY: The Valentine Museum has this site were repatriated to the Pawnee information, as well as oral traditional completed an inventory of human Nation of Oklahoma in 1990–1991. The information provided by members of the remains and associated funerary objects, 321 unassociated funerary objects are: Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma. in consultation with the appropriate 15 brass/copper bells, one brass/copper Indian Tribes or Native Hawaiian ornament, one bridle bit, two bullet Determinations Made by History organizations, and has determined that molds, five chalk fragments, four Nebraska there is a cultural affiliation between the human remains and associated funerary chipped stone flakes, five chipped stone Officials of History Nebraska have tools, two clasp knives, three clay objects and present-day Indian Tribes or determined that: lumps, three cloth and leather Native Hawaiian organizations. -

The Virginia Indians Meet the Tribes Student Activity Book

The Virginia Indians Meet the Tribes http://virginiaindians.pwnet.org/history/modern_indians.php Student Activity Book Virginia Department of Education © 2013 Table of Contents Introduction………..…………………..…………...1 Virginia’s First People: 1607………………………2 Adaptations & Occupations: 1607…………….3 Adaptations & Occupations: Today…………..4 The Virginia Indian Pow Wow……………………6 Regalia………………………………………………7 Similarities & Differences………………….……..8 Tech it Up: Find out More!………………………..9 Introduction European colonists arriving in Virginia may have been greeted with, "Wingapo." Indians have lived in what is now called Virginia for thousands of years. While we are still learning about the people who inhabited this land, it is clear that Virginia history did not begin in 1607. If you ask any Virginia Indian, "When did you come to this land?" he or she will tell you, "We have always been here." http://virginiaindians.pwnet.org/history/index.php 1 Virginia’s First People http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/arch_NET/timeline/late_wood_map.htm There were three major language families at the time of European contact in 1607: the Siouan, the Algonquian, and the Iroquoian. In the video, Keenan taught us that today, there are eleven different Virginia Indian tribes recognized by the Commonwealth of Virginia. This activity book will give you the opportunity to compare Virginia’s first people from 1607 to Virginia’s first people today. You will also be able to compare your own life and traditions to those of a Virginia Indian child today. 2 Adaptations & Occupations: 1607 Directions: Draw and label pictures that show how Virginia’s first people adapted to their environment and what kinds of occupations they had in 1607. -

The Monacan Indian Nation in the Twentieth Century

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2012 A question of Indian identity in the Plecker Era: The onM acan Indian Nation in the twentieth century Jennifer Marie Huff James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Huff, Jennifer Marie, "A question of Indian identity in the Plecker Era: The onM acan Indian Nation in the twentieth century" (2012). Masters Theses. 240. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/240 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Question of Indian Identity in the Plecker Era: The Monacan Indian Nation in the Twentieth Century Jennifer M. Huff A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History May 2012 Dedication For my mom, Julie. Words cannot express how your love, support, and encouragement have given me the strength to endure through life’s many challenges. ii Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my thesis director, Dr. Philip Dillard for his patience, guidance, and support through the thesis process. Words cannot express my gratitude and I am eternally thankful for your advice and dedication in seeing my thesis through. I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. -

Powhatan People

POWHATAN PEOPLE STUDENT ACTIVITY BOOK Grades 2-5 www.thevalentine.org education@ thevalentine.org MAPPING VIRGINIA Using the words below, draw the geographic features that were important to the Powhatan people on the map of Virginia. Appalachian Plateau Great Dismal Swamp Blue Ridge Mountains James River Chesapeake Bay Valley and the Ridge Costal Plain WORD SEARCH Ahone Monacan Rappahannock Algonquian Nansemond Sinew Canoe Nottoway Tidewater Chesapeake Oke Wampum Chickahominy Pamunkey Werowance Deer Patawomeck Yehaken Mataponi Pocahontas CORNFIELD MAZE DAY 1 The Powhatan grew a variety of crops that changed according to the seasons, including corn, beans and squash. START FINISH Imagine you are a Powhatan child helping your mother. She sent you to pick corn, but you can't find your way out of the cornfield! Follow the maze from start to finish to escape the cornfield. TRIBES OF VIRGINIA DAY 1 Check out these seals belonging to Virginia state-recognized tribes. Seals often include natural resources, animals and symbols. In the circle, draw a seal for Chief Powhatan's tribe. What would you include? POWHATAN VILLAGE Use your imagination to add some color and detail to this Powhatan village! Can you add a garden outside the village? What crops would you include? Take it further: research the Powhatan online and learn about Powhatan people in our community today. ANSWER KEY DAY 1 WORD SEARCH CORNFIELD MAZE The Valentine's Student Programs are generously supported by.