Transcribed Audio Interview with Erwin Bloch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

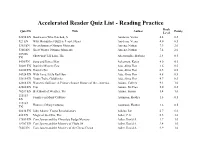

Accelerated Reader Quiz List

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Book Quiz ID Title Author Points Level 32294 EN Bookworm Who Hatched, A Aardema, Verna 4.4 0.5 923 EN Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Ears Aardema, Verna 4.0 0.5 5365 EN Great Summer Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.9 2.0 5366 EN Great Winter Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.4 2.0 107286 Show-and-Tell Lion, The Abercrombie, Barbara 2.4 0.5 EN 5490 EN Song and Dance Man Ackerman, Karen 4.0 0.5 50081 EN Daniel's Mystery Egg Ada, Alma Flor 1.6 0.5 64100 EN Daniel's Pet Ada, Alma Flor 0.5 0.5 54924 EN With Love, Little Red Hen Ada, Alma Flor 4.8 0.5 35610 EN Yours Truly, Goldilocks Ada, Alma Flor 4.7 0.5 62668 EN Women's Suffrage: A Primary Source History of the...America Adams, Colleen 9.1 1.0 42680 EN Tipi Adams, McCrea 5.0 0.5 70287 EN Best Book of Weather, The Adams, Simon 5.4 1.0 115183 Families in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 115184 Homes in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 60434 EN John Adams: Young Revolutionary Adkins, Jan 6.7 6.0 480 EN Magic of the Glits, The Adler, C.S. 5.5 3.0 17659 EN Cam Jansen and the Chocolate Fudge Mystery Adler, David A. 3.7 1.0 18707 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of Flight 54 Adler, David A. 3.4 1.0 7605 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of the Circus Clown Adler, David A. -

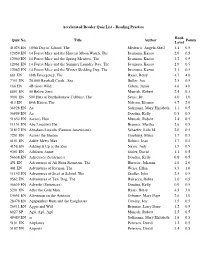

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 41025 EN 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 12059 EN 14 Forest Mice and the Harvest Moon Watch, The Iwamura, Kazuo 2.9 0.5 12060 EN 14 Forest Mice and the Spring Meadow, The Iwamura, Kazuo 3.2 0.5 12061 EN 14 Forest Mice and the Summer Laundry Day, The Iwamura, Kazuo 2.9 0.5 12062 EN 14 Forest Mice and the Winter Sledding Day, The Iwamura, Kazuo 3.1 0.5 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 7351 EN 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8001 EN 50 Below Zero Munsch, Robert 2.4 0.5 9001 EN 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 36928 EN Aa Salzmann, Mary Elizabeth 1.1 0.5 36909 EN Aa Doudna, Kelly 0.5 0.5 51654 EN Aaron's Hair Munsch, Robert 2.4 0.5 11151 EN Abe Lincoln's Hat Brenner, Martha 2.6 0.5 31812 EN Abraham Lincoln (Famous Americans) Schaefer, Lola M. 2.0 0.5 7201 EN Across the Stream Ginsburg, Mirra 1.7 0.5 6101 EN Addie Meets Max Robins, Joan 1.7 0.5 4158 EN Adding It Up at the Zoo Nayer, Judy 1.5 0.5 9301 EN Addition Annie Gisler, David 1.1 0.5 56638 EN Adjectives (Sentences) Doudna, Kelly 0.8 0.5 451 EN Adventures of Ali Baba Bernstein, The Hurwitz, Johanna 4.6 2.0 401 EN Adventures of Ratman, The Weiss, Ellen 3.3 1.0 11152 EN Adventures of Snail at School, The Stadler, John 2.5 0.5 9562 EN Adventures of Taxi Dog, The Barracca, Debra 3.0 0.5 56639 EN Adverbs (Sentences) Doudna, Kelly 0.9 0.5 -

Gaslightpdffinal.Pdf

Credits. Book Layout and Design: Miah Jeffra Cover Artwork: Pseudodocumentation: Broken Glass by David DiMichele, Courtesy of Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco ISBN: 978-0-692-33821-6 The Writers Retreat for Emerging LGBTQ Voices is made possible, in part, by a generous contribution by Amazon.com Gaslight Vol. 1 No. 1 2014 Gaslight is published once yearly in Los Angeles, California Gaslight is exclusively a publication of recipients of the Lambda Literary Foundation's Emerging Voices Fellowship. All correspondence may be addressed to 5482 Wilshire Boulevard #1595 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Details at www.lambdaliterary.org. Contents Director's Note . 9 Editor's Note . 11 Lisa Galloway / Epitaph ..................................13 / Hives ....................................16 Jane Blunschi / Snapdragon ................................18 Miah Jeffra / Coffee Spilled ................................31 Victor Vazquez / Keiki ....................................35 Christina Quintana / A Slip of Moon ........................36 Morgan M Page / Cruelty .................................51 Wayne Johns / Where Your Children Are ......................53 Wo Chan / Our Majesties at Michael's Craft Shop ..............66 / [and I, thirty thousand feet in the air, pop] ...........67 / Sonnet by Lamplight ............................68 Yana Calou / Mortars ....................................69 Hope Thompson/ Sharp in the Dark .........................74 Yuska Lutfi Tuanakotta / Mother and Son Go Shopping ..........82 Megan McHugh / I Don't Need to Talk -

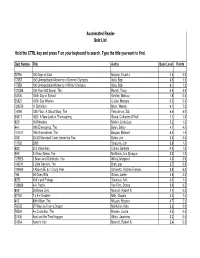

KNAPP AR LIST for Web Site

Accelerated Reader Quiz List Hold the CTRL key and press F on your keyboard to search. Type the title you want to find. Quiz Number Title Author Book Level Points 75796 100 Days of Cool Murphy, Stuart J. 2.6 0.5 17357 100 Unforgettable Moments in Summer Olympics Italia, Bob 6.5 1.0 17358 100 Unforgettable Moments in Winter Olympics Italia, Bob 6.1 1.0 122356 100-Year-Old Secret, The Barrett, Tracy 4.4 4.0 74705 100th Day of School Schiller, Melissa 1.8 0.5 35821 100th Day Worries Cuyler, Margery 3.0 0.5 128370 11 Birthdays Mass, Wendy 4.1 7.0 14796 13th Floor: A Ghost Story, The Fleischman, Sid 4.4 4.0 53617 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace, Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1.0 8251 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda Lee 5.2 1.0 661 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 101417 19th Amendment, The Burgan, Michael 6.4 1.0 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 11592 2095 Scieszka, Jon 3.8 1.0 6201 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara 4.0 1.0 6651 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague 3.3 1.0 125923 3 Bears and Goldilocks, The Willey, Margaret 4.3 0.5 140211 3 Little Dassies, The Brett, Jan 3.7 0.5 109460 4 Kids in 5E & 1 Crazy Year Schwartz, Virginia Frances 3.8 6.0 166 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8252 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. -

Gr 11 Term 4 2019 EFAL Literature Summary.Pdf

ENGLISH FIRST ADDITIONAL LANGUAGE Literature Summary Grade 11 TERM 4 A message from the NECT National Education Collaboration Trust (NECT) DEAR TEACHERS This learning programme and training is provided by the National Education Collaboration Trust (NECT) on behalf of the Department of Basic Education (DBE)! We hope that this programme provides you with additional skills, methodologies and content knowledge that you can use to teach your learners more effectively. WHAT IS NECT? In 2012 our government launched the National Development Plan (NDP) as a way to eliminate poverty and reduce inequality by the year 2030. Improving education is an important goal in the NDP which states that 90% of learners will pass Maths, Science and languages with at least 50% by 2030. This is a very ambitious goal for the DBE to achieve on its own, so the NECT was established in 2015 to assist in improving education and to help the DBE reach the NDP goals. The NECT has successfully brought together groups of relevant people so that we can work collaboratively to improve education. These groups include the teacher unions, businesses, religious groups, trusts, foundations and NGOs. WHAT ARE THE LEARNING PROGRAMMES? One of the programmes that the NECT implements on behalf of the DBE is the ‘District Development Programme’. This programme works directly with district officials, principals, teachers, parents and learners; you are all part of this programme! The programme began in 2015 with a small group of schools called the Fresh Start Schools (FSS). Curriculum learning programmes were developed for Maths, Science and Language teachers in FSS who received training and support on their implementation. -

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Tuesday, 11/06/12, 11:47 AM

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Tuesday, 11/06/12, 11:47 AM McGee Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Book Point Fiction/ ID Title Author Level Value Language Non-fiction 46618 Cats! Brimner, Larry Dane 0.3 0.5 English Fiction 46456 Come Here, Tiger! Moran, Alex 0.3 0.5 English Fiction 75994 Todd's Box Sullivan, Paula 0.3 0.5 English Fiction 31584 Big Brown Bear McPhail, David 0.4 0.5 English Fiction 36573 Big Egg Coxe, Molly 0.4 0.5 English Fiction 41850 Clifford Makes a Friend Bridwell, Norman 0.4 0.5 English Fiction 42156 I Am Lost! Wilhelm, Hans 0.4 0.5 English Fiction 31598 I See, You Saw Karlin, Nurit 0.4 0.5 English Fiction 76155 Rick Is Sick McPhail, David 0.4 0.5 English Fiction 64100 Daniel's Pet Ada, Alma Flor 0.5 0.5 English Fiction 35988 Day I Had to Play with My Sister, The Bonsall, Crosby 0.5 0.5 English Fiction 49483 Down on the Farm Lascaro, Rita 0.5 0.5 English Fiction 31542 Mine's the Best Bonsall, Crosby 0.5 0.5 English Fiction 73104 Scat, Cats! Holub, Joan 0.5 0.5 English Fiction 49858 Sit, Truman! Harper, Dan 0.5 0.5 English Fiction 60939 Tiny Goes to the Library Meister, Cari 0.5 0.5 English Fiction 35665 What Day Is It? Trimble, Patti 0.5 0.5 English Fiction 31594 B. Bears Ride the Thunderbolt, The Berenstain, Stan 0.6 0.5 English Fiction 50094 Big, Big Wall, The Howard, Reginald 0.6 0.5 English Fiction 42150 Don't Cut My Hair! Wilhelm, Hans 0.6 0.5 English Fiction 45501 Honey Helps Godwin, Laura 0.6 0.5 English Fiction 62797 I Can Do It All Pearson, Mary E. -

Independent Leveled Books Fourth Grade Brooks Crossing Elementary

Independent Leveled Books Fourth Grade Brooks Crossing Elementary Levels M N O P Q R S T U LEVEL M Arthur Accused!, by Marc Brown Arthur and the Big Blow-Up, by Marc Brown Arthur and the Cootie-Catcher, by Marc Brown Arthur and the Crunch Cereal Contest, by Marc Brown Arthur and the Lost Diary, by Marc Brown Arthur and the Popularity Test, by Marc Brown Arthur and the Scare-Your-Pants-Off Club, by Marc Brown Arthur and the TL Contest, by Marc Brown Arthur Makes the Team, by Marc Brown Arthur Rocks with BINKY, by Marc Brown Arthur’s Mystery Envelope, by Marc Brown The Beast in Ms. Rooney’s Room, by Patricia Reilly Giff Fish Face, by Patricia Reilly Giff Flat Stanley, by Jeff Brown In Aunt Lucy’s Kitchen, by Cynthia Rylant The Invisible Dog, by Dick King-Smith Invisible in the Third Grade, by Margery Cuyler The Island of the Skog, by Steven Kellogg Jigsaw Jones Mystery: The Case of the Christmas Snowman, by James Ruller Junie B. Jones and the Little Monkey Business, by Barbara Park Junie B. Jones and Her Big Fat Mouth, by Barbara Park Junie B. Jones and Some Sneaky Peeky Spying, by Barbara Park Junie B. Jones and the Meanie Jim’s Birthday, by Barbara Park Junie B. Jones and the Mushy Gushy Valentine, by Barbara Park Junie B. Jones and the Stupid Smelly Bus, by Barbara Park Junie B. Jones and the Yucky Blucky Fruitcake, by Barbara Park Junie B. Jones Has a Monster Under Her Bed, by Barbara Park Junie B. -

Book Room Labels Copy2

title author G.R. Level Lexile # of copies theme owner At the Zoo Hastings, Jack A 6 Animals Title I At the Zoo Kloes, Carol A 6 Zoo Title I Baby Chimp Williams, Rebel A 6 Animals Title I Balloons, The Cutting, Jillian A 6 Misc. Title I Big and Small Creasy, Mary-Anne A 6 Concepts Title I Big Chase, The Anderson, Karen A 6 Animals Title I Birthday Cake, The Cowley, Joy A 3 Colors Title I Bunny Hop, The Slater, Teddy A 210L 2 Animals Hiller Chairs Creasy, Mary-Anne A 6 Title I Circus Hastings, Jack A 6 Title I Crash! Buxton, Jane A BR 6 Title I Face Painting Ellis, Julie A 5 Title I Flowers Hoenecke, Karen A 6 Colors Title I Going Places Cahill, Margaret A BR 6 Title I Helicopter over Hawaii Williams, Rebel A 6 Transportation Title I I Wash Cappellini, Mary A BR 6 Title I Look at Me Feely, Jenny A 6 Self Title I My Birthday Party Peters, Catherine A 5 Me MGSD My Painting Hill, Sharon A 6 Title I Present, The Hancock, Kay A BR 6 Title I Push and Pull Parkes, Brenda A 6 Science Title I Shapes Urmston, Kathleen and A 6 Concepts Title I Surprise Inside, The Charles,Karen Evans Ruth A 3 Color Words MGSD What Has Wheels? Hoenecke, Karen A 6 Title I All Dressed Up Mitchell, Claudette C. B 6 Clothes Title I Astronaut Hoenecke,and others Karen B 6 Title I At the Zoo Peters, Catherine B 5 Animals MGSD Beautiful Flowers Enting, Brian B 6 Plants MGSD Cars Hubley, Curtis B 5 Transportation MGSD Chicken Soup Fitros, Pamela B 6 MGSD Clown, The Urmston, Kathleen and B 6 MGSD Colors In the City Evans,Karen Evans Karen and B 6 Colors MGSD Dad Peters,Kathleen Catherine Urmston B 5 Family MGSD title author G.R. -

Footprints 2009

Disclaimer: The club would like to thank AUSA for their contributions towards the publication of Footprints and other events through the year. Opinions expressed in this journal are the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Students Association or the Auckland University Tramping Club. Footprints 2009 The Annual Journal of the Auckland University Tramping Club - Volume 63, 2009 ____________________________________________________________________ Committee 2009 President: David Gauld Captain: Rion Gulley Secretary: Kat Collier Treasurer: Richard Greatrex Social Officers: Charis Wong/Tom Goodman Memberships Officer: Kylie Brewer Hut Officer: Brad Lovett Website Officer: Rob Connolly Publications Officer: Rebecca Caldwell Trips Officer: Craig Smith Safety/Instructional Officer: Anton Gulley Gear Officer: Rowan Brooks Alpine Officer: Miles Mason Duke of Edinburgh Officer: John Deverall Archive Officer: Brian Davies Vice Presidents: Andy Baddeley, Anthea Johnson, Jane Dudley, Owen Lee, Antony Phillips Front Cover Photo Best Scenic Photo of the Year winner: “Lake Daniells” ~ by Keri Yukich ~ "Good use of portrait, like the mist, sharp and well exposed", as commented/judged by Shaun Barnett Centre Insert Photos Mt. Taranaki, Nth Island ~ by Aidan Thorp ~ Lake Matheson, Sth Island (A3 Centrepiece) ~ by Rebecca Caldwell ~ Tongariro-Alpine Crossing Great Walk, Nth Island (via moonlight) ~ by Andy Baddeley~ Back Cover Photo Most Hilarious Photo of the Year winner: “Business as usual” ~ by Erik Tomsen ~ "Excellent -

The Undomestic Goddess

Color-- -1- -2- -3- -4- -5- -6- -7- -8- -9- Text Size-- 10-- 11-- 12-- 13-- 14-- 15-- 16-- 17-- 18-- 19-- 20-- 21-- 22-- 23-- 24 The Undomestic Goddess By Sophie Kinsella Contents Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Sixteen Chapter Seventeen Chapter Eighteen Chapter Nineteen Chapter Twenty Chapter Twenty-one Chapter Twenty-two Chapter Twenty-three Chapter Twenty-four Chapter Twenty-five Chapter Twenty-six The Undomestic Goddess THE DIAL PRESS Also by Sophie Kinsella SHOPAHOLIC & SISTER CAN YOU KEEP A SECRET? SHOPAHOLIC TIES THE KNOT SHOPAHOLIC TAKES MANHATTAN CONFESSIONS OF A SHOPAHOLIC To Linda Evans THE UNDOMESTIC GODDESS A Dial Press Book /July 2005 Published by The Dial Press A Division of Random House, Inc. New York, New York This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. All rights reserved Copyright © 2005 by Sophie Kinsella Book design by Lynn Newmark Endpapers by Dana Leigh Blanchette The Dial Press is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc., and the colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the publisher. ISBN: 0-385-33868-6 Printed in the United States of America Published simultaneously in Canada www. dialpress .com 10 987654321 BVG The Undomestic Goddess Chapter One Would you consider yourself stressed? No. -

Another Record- Setting Obs April Sale Concludes

SATURDAY, APRIL 27, 2019 $68,541,500 for 698 horses sold. The average, which was ANOTHER RECORD- $98,197 a year ago, rose 10.9% to a new sales best of $108,903 and the median rose 7% to $60,000. The four-day buy-back rate SETTING OBS APRIL was 19.7%. It was 18.1% a year ago. AAt the end of the day, it=s all about the horses,@ said OBS SALE CONCLUDES President Tom Ventura. AThe consignors have complete confidence in this sale and they bring top quality. It=s borne itself out, not only in the ring, but also on the racetrack. Which is more important than what they bring in the ring, in my opinion. They have to perform and that keeps the buyers coming back and gets new buyers interested.@ The auction=s top 10-priced lots were all purchased by separate buying interests and reflected the sale=s deep buying bench, according to Ventura. AI think the buying bench was very deep and, for the most part, the competition for the top horses wasn=t just two buyers, it was multiple buyers that got in on some of these top horses. And the people that brought the very top horses were spread around. Down below the very top was strong as well.@ The international buying bench continued to be a major $1.3-million son of Into Mischief | Photos by Z presence at the April sale, with Narvick International and Korea=s K.O.I.D. Co., Ltd among the top five buyers. -

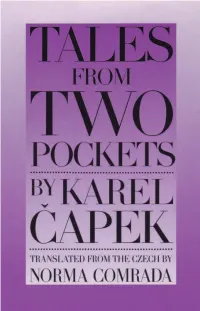

Tales from Two Pockets

1 OTHER WORKS BY KAREL CAPEK FROM CATBIRD PRESS Toward the Radical Center: A Karel Capek Reader, edited by Peter Kussi, foreword by Arthur Miller Apocryphal Tales, trans. Norma Comrada Three Novels, trans. M. & R. Weatherall War with the Newts, trans. Ewald Osers Cross Roads, trans. Norma Comrada Talks with T. G. Masaryk, trans. Michael Henry Heim 2 TALES FROM TWO POCKETS by Karel Capek Translated from the Czech and with an introduction by Norma Comrada CATBIRD PRESS A Garrigue Book 3 English translation © 1994 Catbird Press Introduction © 1994 Norma Comrada CATBIRD PRESS 16 Windsor Road, North Haven, CT 06473 www.catbirdpress.com [email protected] 203-230-2391 Our books are distributed to the trade by Independent Publishers Group Sony ISBN 978-1-936053-03-2 Kindle ISBN 978-1-936053-04-9 Adobe ISBN 978-1-936053-05-6 See page 376 for the translator’s acknowledgments. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Capek, Karel, 1890-1938. [Povídky z druhé kapsy. English] Tales from two pockets / by Karel Capek ; translated from the Czech and with an introduction by Norma Comrada. -- 1st ed. “Originally collected in the vo\lumes Povídky z jedné kapsy and Povídky z druhé kapsy in 1929"--CIP verso t.p. “A Garrigue book.” ISBN 0-945774-25-7 : $14.95 1. Capek, Karel, 1890-1938--Translations into English. I. Capek, Karel, 1890-1938. Povídky z jedné kapsy. English. 1994. II. Comrada, Norma. III. Title. PG5038.C3A23 1994 891.8’635--dc20 93-42204 CIP 4 CONTENTS Introduction 6 Tales from One Pocket Dr. Mejzlik’s Case 13 The Blue Chrysanthemum 18 The Fortuneteller 25 The Clairvoyant 31 The Mystery of Handwriting 39 Proof Positive 47 The Experiment of Professor Rouss 53 The Missing Letter 62 Stolen Document 139/VII Sect.