FINAL Report Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP: WHAT EVERYONE NEEDS to KNOW TEACHING NOTES David Bornstein and Susan Davis

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP: WHAT EVERYONE NEEDS TO KNOW TEACHING NOTES David Bornstein and Susan Davis SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP: WHAT EVERYONE NEEDS TO KNOW TEACHING NOTES David Bornstein and Susan Davis Dear Faculty, We are delighted that you are considering using our new book in your classroom. By using this resource, you are helping to awaken the changemaker inside each of your students. Your action will inspire others to act. The field of social entrepreneurship education is being created and shaped by a new generation of innovative academics and teachers who understand social change and entrepreneurship. You come from many different disciplines. We welcome hearing from you about how you are using this book, how to improve this guide and what other ideas you have to advance this field. With warm wishes, David and Susan SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP: WHAT EVERYONENEEDSTO KNOW 2 INTRODUTION TO TEACHING NOTES The teaching notes were created for faculty interested in teaching social entrepreneurship using the Social Entrepreneurship: What Everyone Needs to Know book by David Bornstein and Susan Davis. The teaching notes includes summaries of the three main sections of the book along with an outline of the section, quiz questions, additional readings and support materials for classroom lectures. We are interested in receiving your feedback on how you use the book and suggestions for future updates to the teaching notes. Please send your suggestions to: Susan Davis [email protected] or Debbi Brock, who is also using the book in one of her courses [email protected] BOOK SUMMARY Social entrepreneurship has grown into a global movement that is producing solutions to many of the world‗s toughest problems and transforming the way we think about social change. -

Oregon Wine History Project™ Interview Transcript: Dick & Nancy Ponzi

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Oregon Wine History Transcripts Bringing Vines to the Valley 5-22-2012 Oregon Wine History Project™ Interview Transcript: Dick & Nancy Ponzi Dick Ponzi Nancy Ponzi Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/owh_transcripts Part of the Oral History Commons, and the Viticulture and Oenology Commons Recommended Citation Ponzi, Dick and Ponzi, Nancy, "Oregon Wine History Project™ Interview Transcript: Dick & Nancy Ponzi" (2012). Oregon Wine History Transcripts. Transcript. Submission 6. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/owh_transcripts/6 This Transcript is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Transcript must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. Dick and Nancy Ponzi Transcript subject to Rights and Terms of Use for Material Posted in Digital Commons@Linfield This interview was conducted with Dick Ponzi (DP) and Nancy Ponzi (NP) in July of 2010 at Ponzi Vineyards in Dundee, Oregon. The primary interviewer was Jeff D. Peterson (JDP). Additional support provided by videographers Mark Pederson and Barrett Dahl. The duration of the interview is 56 minutes, 58 seconds. [00:00] JDP: We're going to be talking about the early years of the Oregon Wine Industry, the second time around after prohibition. -

Downloads the Data Into Fundación Paraguaya’S Stoplight Database

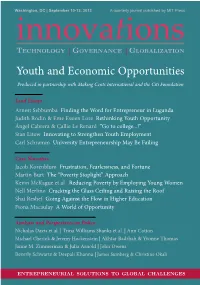

Washington, DC | September 10-12, 2013 A quarterly journal published by MIT Press innovations TECHNOLOGY | GOVERNANCE | GLOBALIZATION Youth and Economic Opportunities Produced in partnership with Making Cents International and the Citi Foundation Lead Essays Arnest Sebbumba Finding the Word for Entrepreneur in Luganda Judith Rodin & Eme Essien Lore Rethinking Youth Opportunity Ángel Cabrera & Callie Le Renard “Go to college...!” Stan Litow Innovating to Strengthen Youth Employment Carl Schramm University Entrepreneurship May Be Failing Case Narrative Jacob Korenblum Frustration, Fearlessness, and Fortune Martin Burt The “Poverty Stoplight” Approach Kevin McKague et al. Reducing Poverty by Employing Young Women Nell Merlino Cracking the Glass Ceiling and Raising the Roof Shai Reshef Going Against the Flow in Higher Education Fiona Macaulay A World of Opportunity Analysis and Perspectives on Policy Nicholas Davis et al. | Trina Williams Shanks et al. | Ann Cotton Michael Chertok & Jeremy Hockenstein | Akhtar Badshah & Yvonne Thomas Jamie M. Zimmerman & Julia Arnold | John Owens Beverly Schwartz & Deepali Khanna | James Sumberg & Christine Okali ENTREPRENEURIAL SOLUTIONS TO GLOBAL CHALLENGES Editors Advisory Board Philip Auerswald Susan Davis Iqbal Quadir Bill Drayton Contributing Editor David Kellogg Fiona Macaulay Eric Lemelson Granger Morgan Senior Editor Jacqueline Novogratz Winthrop Carty James Turner Managing Editor Xue Lan Michael Youngblood Editorial Board Senior Researcher David Audretsch Adam Hasler Matthew Bunn Maryann Feldman -

Pinotfile Vol 9 Issue 31

Cabernet is a Bordello, Pinot Noir is a Casino Volume 9, Issue 31 October 10, 2013 David Adelsheim: A “Latecomer” Oregon Wine Pioneer David Adelsheim likes to call himself a “latecomer” when talk turns to the pioneers of Oregon’s modern wine industry. Although Richard Sommer, David Lett, Charles Coury, Dick Erath and Dick Ponzi preceded him by a few years in planting vineyards and establishing wineries in Oregon, David not only founded an iconic Willamette Valley winery, he became a revered figure in Oregon wine after having participated as a respected spokesperson on practically every important issue facing the Oregon wine industry through the years. Despite his prestigious accomplishments, he remains modest and unassuming, with a charming sense of humor, all attributes that bring him much-deserved respect from his colleagues in Oregon. David was uniquely one of the name early Oregon wine pioneers that did not immigrate to Oregon. Although he moved to Portland from Kansas City with his family in 1954, he spent his formative years in Portland. After studying at University of California at Berkeley and in Germany, he received a bachelor’s degree in German literature from Portland State University. David became intrigued with artisan wines after a summer trip to Europe in 1969 with his spouse Ginny, who was a talented sculptor and artist. He soon immersed himself in the literature of winemaking, and dreamed of planting a vineyard in Oregon. In 1971, the Adelsheims had a chance meeting with Dick Erath and Bill Blosser at a May Day party. They directed the couple to seek out a south-facing slope with Jory soil appropriate for viticulture. -

The Story of Phelps Creek Vineyards by Robert A. Morus--Founder

The Story of Phelps Creek Vineyards by Robert A. Morus--Founder Growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area embedded familiarity with Napa, Sonoma and Santa Clara Valleys. My family moved to Danville, California in 1964, just when Robert Mondavi's ambition, and Napa's renaissance garnered lavish media attention. As a kid, I read the San Francisco Chronicle's coverage of the nascent wine explosion, noting bottles frequently graced our own and friends’ tables. Even Boy Scout trips often passed through the wine country. When canoeing the Russian River, the troop launched next to a vineyard owned by the Italian Swiss Colony winery. All these experiences combined to float a personal appreciation for wine's romance and the beauty of vineyards. Like my father, I flew in the Air Force and eventually became an airline pilot. A professional pilot's career often enables choosing where you live, even if it a means "commuting" to work somewhere else in the world. Wanting to return west, Portland presented a better basing option in comparison to California after joining Delta. Married and originally flying out of Chicago, my wife and I began a process of researching Oregon (1989), envisioning a slow, gradual process to relocate in a perfect place to raise a family, transfer my base of operation and hopefully plant a vineyard. I drew a radius of 90 miles from PDX airport. Delta recently opened an international base at PDX, and I thought living on and operating a small vineyard, with no more than an hour and 1/2 drive to work once a week, would be ideal; it sounded like a beautiful lifestyle. -

Legacy of Family

HOME NEWS/FEATURES FOOD COMMENTARY CELLAR SELECTS EMPOURIUM CALENDAR ALMANAC / DIRECTORIES CONTACT NEWS / FEATURES UPCOMING EVENTS Mimosa Sunday Youngberg Hill, McMinnville | Jun 7, 2020 -Jul 26, 2020 An impromptu Ponzi family portrait in the 1970s: (from left) Luisa, Nancy, Anna Maria, Michel and Dick. Photo provided Barn Swallow Artists Classes at Abbey Road Farm Abbey Road Farm, Carlton | Jun 7, 2020 -Aug 2, 2020 June 1, 2020 Open Mic Nights Oran Mor Artisan Mead, Roseburg | Jun 11, 2020 -Dec Legacy of Family 10, 2020 Comedian Derek Sheen - Left Coast Cellars Ponzi celebrates ve dening decades Left Coast Estate, Rickreall | Jun 13, 2020 Midsommar Rosé Fest 2020 By Mark Stock Lichtenwalter Vineyard, Ribbon Ridge, Newberg | Jun 20, 2020 It’s not exactly the half-century bash Ponzi Vineyards might have scripted, but the « previous 1 2 3 4 5 next » pioneering Oregon label is celebrating nonetheless. The Willamette Valley winery turns 50 years old this year. Prior to the pandemic, there Read the were celebratory plans involving special releases, large gatherings and festive tastings. Oregon Wine Press Ponzi still plans to toast the milestone, albeit in a reformed fashion in keeping with the page by page new normal. While unknowns loom large and the wine industry attempts to survive this di∆cult stretch, there are some certainties. For Ponzi, it’s the winery’s legacy, running deep and greatly impacting the Paciƒc Northwest wine conversation. There are many chapters to the Ponzi winery story. From ƒnding a New World home for lesser-known Old World grape varieties like Arneis and Dolcetto, to promoting diversity in the workplace and helping Chardonnay’s renaissance in the Willamette Valley, the company has always been both involved and instrumental. -

OVERVIEW OREGON Content Contributed by John Griffin, Imperial Beverage

WINE OVERVIEW OREGON Content contributed by John Griffin, Imperial Beverage Closely review the syllabus for this wine level to determine just what items require your attention in each of the region/country overview documents. If I were a bunch of Pinot Noir grapes, and I couldn’t speak French, then I would want to live in the Dundee Hills of Oregon’s Willamette Valley. It is widely agreed that outside of the Grand Cru vineyards of France’s Burgundy region that Oregon is probably the best place on earth to cultivate the finicky Pinot Noir grape. Let’s find out why. CLIMATE Oregon’s overall climate can best be described as mild. While it is famous for wet, gray winters, during the summer growing season it is usually sunny and dry. And, most importantly, it is not too hot. This is critical for growing Pinot Noir, which is a relatively thin-skinned grape and cannot thrive in a hot zone. This provides a significant contrast to California where, for too long, Pinot Noir was often planted in micro climates that were way too warm causing the resulting wines to have a stewed tomato flavor, like drinking ketchup. (Yum). The general physics of this are simple: when wine grapes mature too quickly in a hot climate the fructose rises while the acids drop out producing wines that are flabby, soft, unbalanced and often a little too sweet. Typical examples of this are California Chardonnays that taste like pineapple juice or Australian Shiraz that drinks like blackberry syrup. Oregon almost never has this problem. -

Ponzi Vineyards Dr. Russell Smithyman

2017 LIVE Board of Directors | This ballot is intended for LIVE Official Ballot members to vote for their choices for the Board of Directors. Vote for no more than five choices by selecting a checkbox or writing RE-ELECTION candidate names in the blank space provided. Each member serves a two-year term. Don Crank | A to Z Wineworks This slate of nominees was selected by the LIVE Board of Directors and is intended to be fair and representative of the demographics and geography of the membership and the interest of organizational mission. Any member interested in serving on ELECTION the Board of Directors may contact our office with a letter of intent. LIVE members may also nominate a director from the floor at the Annual Meeting. Any nomination from the floor must be seconded to be added to the ballot for the full vote of the membership. Leigh Bartholomew | Results Partners Additional Notes and Instructions: The number of ballots received is sufficient to Luisa Ponzi | Ponzi Vineyards meet the quorum requirements of this corporation. Affix the signature of an officer or agent representing the voting member and write the name of the vineyard or winery member, the printed name of the authorized representative, and date. If submitting by mail or e-mail, complete the ballot and send to: Jess Sandrock | Chemeketa Community College [email protected] | LIVE, PO Box 5185, Salem, OR 97304 E-mailed/mailed ballots must be received by April 10, 2017 to be counted. Dr. Russell Smithyman | Ste Michelle Wine Estates Your vineyard or winery name Write-in up to five candidates Please be sure to indicate the vineyard or winery each write-in represents Print your name Sign your name Date NOMINEE BIOGRAPHIES Don Crank | Re-election Jessica Sandrock | Election Don Crank is The Red Winemaker at A to Z wineworks, since 2015. -

Ponzi Vineyards Tohu Wines

© PinotFile PinotFile: The Premier Online Newsletter Devoted to Skewis Wines Pinot Hank and Maggie Skewis have been quietly making high quality, complex Volume 3, Issue 13 Pinot Noirs from vineyards in Sonoma and Mendocino Counties since November 10, 2003 1994. The first grapes were purchased in 1994 from the Floodgate Vine- yard in Mendocino County’s Anderson Valley. The philosophy here is seeking quality grapes from low-yielding vines, gently crushing the grapes, then fermenting very warm for maximum extraction and finall- Pinot Noir is easily presseing into Burgundian oak barrels for primary and secondary susceptible to “bottle malolactic fermentation. The Pinots are bottled after 18 months of barrel shock”. After bot- aging, unfined and unfiltered, and aged an additional 4 to 6 months prior tling, Pinot Noir is to release. The extraordinary 2001 vintage wines have been released on a often flat, simple, very selective basis. Each bottling is $44. and insipid. 6 months after bot- Skewis Floodgate Vineyard Anderson Valley Pinot Noir 2001 In the tling, the condition reaches a nadir and past Parker has called this wine a copy of a top-flight grand cru Riche- the wine starts com- bourg. The vineyard is at the far western end of the Anderson Valley on a ing back. After 1 steep southerly slope at 750 feet elevation. The soil is poor and the vines year, the wine is are not vigorous. Frequent summer fog and wind tempers the high after- about the same as noon temperatures. The fruit is a 50-50 blend of Pommard and Martini when it was bottled and is getting even clones sourced from the same vine rows each year. -

Guide to the Ponzi Vineyards Collection

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Linfield Archives Finding Aids Linfield Archives 10-27-2015 Guide to the Ponzi Vineyards Collection Linfield College Archives Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/lca_findingaids Part of the Viticulture and Oenology Commons Recommended Citation Linfield College Archives, "Guide to the Ponzi Vineyards Collection" (2015). Linfield Archives Finding Aids. Finding Aid. Submission 18. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/lca_findingaids/18 This Finding Aid is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Finding Aid must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. Dick and Nancy Ponzi Guide to the Ponzi Vineyards Collection 1970-2009 Creator: Dick and Nancy Ponzi Title: Ponzi Vineyards Collection Dates: 1970-2009 Quantity: 2.5 linear feet Collection Number: OWHA04 Summary: This collection details the history of Ponzi Vineyards, founded by Dick and Nancy Ponzi. It includes information regarding events at the vineyard as well as the winery business. Included are articles showcasing the accolades given to the wine made at Ponzi Vineyards and the history of the work that the Ponzis have done to create their winery, as well as the contributions of other individuals. Digital items selected to highlight the collection are available here: http://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/owha_ponzi/. -

Voters' Pamphlet

Elections Division Washington 3700 SW Murray Blvd. Beaverton, OR 97005-2365 County www.co.washington.or.us voters’ pamphlet VOTE-BY-MAIL PRIMARY ELECTION May 18, 2010 To be counted, voted ballots must be in our office by 8:00 pm on May 18, 2010 ATTENTION This is the beginning of your county voters’ pamphlet. The Washington County county portion of this joint voters’ pamphlet is inserted in Board of County the center of the state portion. Each page of the county voters’ pamphlet is clearly marked with a color bar on the Commissioners outside edge. All information contained in the county por- tion of this pamphlet has been assembled and printed Tom Brian, Chair by Rich Hobernicht, County Clerk-Ex Officio, Director Dick Schouten, District 1 Washington County Assessment & Taxation. Desari Strader, District 2 Roy Rogers, District 3 Dear Voter: Andy Duyck, District 4 This pamphlet contains information for several districts and there may be candidates/measures included that are not on your ballot. If you have any questions, call 503-846-5800. WC-2 WC-3 WASHINGTON COUNTY Commissioner at Large Commissioner at Large Andy Dick Duyck Schouten OCCUPATION: Owner, Duyck OCCUPATION: Washington County Machine; Farmer; County Commissioner Commissioner OCCUPATIONAL BACKGROUND: OCCUPATIONAL BACKGROUND: Attorney Same as occupation EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND: EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND: UCLA Law School, JD; Santa Clara Portland Community College; University, BS Political Science Machine Technology; Hilhi PRIOR GOVERNMENTAL EXPERIENCE: Washington County PRIOR GOVERNMENTAL -

Archives a Virtual Trip to Ponzi Vineyards

The WineKnitter THE JOURNAL ABOUT ME An adventure into the world of wine, spirits, food, travel...and so much more! A Virtual Trip to Ponzi Vineyards RSS Feed 5/31/2020 Archives In case you haven’t heard, Willamette Valley AVA in Oregon is an ideal place for growing and producing cool-climate varieties of wine, in particular, its award-winning Pinot Noir, which the May 2020 region is best known for. Other grape varieties that do well here include Pinot Gris, Pinot April 2020 Blanc, Chardonnay and Riesling. March 2020 February 2020 January 2020 December 2019 November 2019 October 2019 September 2019 August 2019 July 2019 June 2019 May 2019 April 2019 March 2019 February 2019 January 2019 December 2018 November 2018 October 2018 September 2018 August 2018 July 2018 June 2018 May 2018 Photo courtesy of Willamette Valley Wineries April 2018 Willamette Valley is located in western Oregon and is Oregon’s largest AVA stretching over 150 March 2018 miles long and 60 miles wide. It borders the Columbia River to the north and runs south to the February 2018 Calapooya Mountains outside Eugene. Willamette Valley has seven appellations within its January 2018 borders and has the largest concentration of wineries and vineyards in Oregon. There are December 2017 approximately 23,524 vineyard acres planted and it is home to 564 wineries. November 2017 October 2017 September 2017 August 2017 July 2017 June 2017 May 2017 April 2017 March 2017 February 2017 January 2017 December 2016 November 2016 October 2016 September 2016 August 2016 July 2016 June 2016 May 2016 April 2016 March 2016 February 2016 January 2016 December 2015 November 2015 October 2015 September 2015 This is a cool-climate, maritime region named after the Willamette River that runs through the August 2015 heart of it.