Historic Bridges of Crawford County Pennsylvania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zebra Mussels Invade Conneaut Lake by Deborah Weisberg

photo-U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Wildlife and S. Fish photo-U. by Deborah Weisberg While Conneaut Lake, Pennsylvania’s largest natural lake, to any hard surface or structure including the shells of draws thousands of anglers and boaters each year, it’s now other mussels. If enough of them encrust the entire native hosting unwanted residents, too. mussel, it won’t be able to open, and it will eventually die.” Zebra mussels, an exotic invader first spotted in the “Once they establish and multiply, they are almost Great Lakes in the mid-1980s, have been found in the impossible to eliminate, particularly in a natural fishery,” 925-acre glacial lake and its outflow in Crawford County, said Woomer. “If it got dire, you could drain a reservoir, at raising new environmental concerns. least theoretically. But, you can’t drain a natural lake. And, “People have called me astounded that they are seeing chemicals aren’t an option anywhere, because you would zebra mussels everywhere in Conneaut Lake this year. wind up harming other aquatic animals.” Whereas last year, they saw just three,” said Tim Wilson, Zebra mussels are a new headache for the Conneaut Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission (PFBC) fisheries Lake Aquatic Management Association (CLAMA), which biologist. “One of our seasonal employees was fishing the already has its hands full trying to control vegetation in outflow and saw them everywhere, too.” a way that satisfies all users of the lake. Anglers come for “It shows you how quickly they can proliferate and why the trophy bass, northern pike and panfish while boaters we put so much effort into public education.” are drawn to the lack of horsepower restrictions. -

Water Resources

WATER RESOURCES Major Tributaries The French Creek watershed has ten major tributaries whose sub-basins cover at least 50 square miles (Figure 3). In addition, those major sub-basins can be broken down further into the Pennsylvania State Water Plan designated small watersheds (Figure 13). The PA portion of the main stem of French Creek is classified as a warm water fishery (WWF) by the PA Department of Environmental Protection’s Water Quality Standards (PA Title 25, Chapter 93). West Branch of French Creek The West Branch of French Creek originates in Chautauqua County, New York and flows southwest into Erie County, Pennsylvania before turning south. It joins French Creek from the right side (facing downstream), near Wattsburg, at river mile 84.42 and drains 77.7 square miles. It drains portions of Northeast, Greenfield, and Venango townships and Wattsburg Borough in Pennsylvania. The low gradient West Branch and all of its tributaries are classified as WWF. The West Branch sub-basin contains the most extensive wetlands, including rare fens, of any Pennsylvania headwater area. Although this sub-basin still contains blocks of contiguous forest and undeveloped riparian areas, it is beginning to see development pressure from the city of Erie and North East. Work by Dr. J. Stauffer, et al, Penn State University, and other historic records have documented 26 species of fish from the West Branch sub-basin (Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, 1992). These include the PA threatened mountain brook lamprey (Ichthyomyzon greeleyi), and Ohio lamprey (Ichthyomyzon bdellium). According to surveys by WPC biologists, this stream also supports 13 freshwater mussel species, including a “viable population of the [former] federal candidate Epioblasma triqueta (snuffbox)” (Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, 1994). -

Washington Townshipmulti- Municipalcomprehensive Plan

THE BOROUGHOF EDINBORO, FRANKLIN TOWNSHIP, AND WASHINGTON TOWNSHIPMULTI- MUNICIPALCOMPREHENSIVE PLAN JUNE2005 This project was financed, in part, by a Land Use Planning and Technical Assistance Program (LUPTAP) grant from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Community and Economic Development TABLEOF CONTENTS PAGE NUMBER The Multi-Municipal Plan Why a New Plan? 1 The Comprehensive Plan - The Process and the Plan 1 What is Required in a Plan 2 The Process of Input 3 Local Leaders’ Questionnaire 3 Town Hall Meetings Washington Edinboro Franklin Summary Public Meeting Results 9 Washington Township 9 Borough of Edinboro 10 Franklin Township 13 Citizen Survey 15 Summary 18 Demographics and Census Data 19 Community Development Objectives 22 Land Use and Natural Resources 23 Introduction 23 Existing Land Use 23 Growing Greener 24 Option 1 26 Option 2 26 Current Land Use Controls 27 Edinboro 28 Franklin Township 30 Washington Township 31 Summary 33 The Community Resource Inventory/Environmental Considerations 34 Wetlands 34 Floodplains 34 State Game Lands and Prime Agriculture Soils 34 Natural Heritage Study 34 The Future Land Use Plan 35 Land Use Policies 36 Agricultural Protection 37 Housing 38 Edinboro 39 Franklin 39 Washington 39 Housing Plan 41 Transportation 42 Transit 42 Roads and Highways 43 Traffic Volumes 44 Safety Issues 45 Bikeways 47 Citizen Concerns 48 Transportation Plan 48 Transit 49 Bikeways 49 The Highway Network 51 Safety Projects 51 Special Corridor Studies 51 Other Potential Transportation Projects 53 Community -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

Geohydrology and Water Quality of the Unconsolidated Deposits in Erie County, Pennsylvania

Geohydrology and Water Quality of the Unconsolidated Deposits in Erie County, Pennsylvania by Theodore F. Buckwalter, Curtis L. Schreffler, and Richard E. Gleichsner U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 95-4165 Prepared in cooperation with the ERIE COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Lemoyne, Pennsylvania 1996 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director The use of trade, product, industry, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. For additional information write to: Copies of this report may be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Earth Science Information Center 840 Market Street Open-File Reports Section Lemoyne, Pennsylvania 17043-1586 Box 25286, MS 517 Denver Federal Center Denver, Colorado 80225 CONTENTS Abstract....................................................................^ 1 Introduction..................................................................................................^ 2 Purpose and scope....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Well-numbering system.............................................................................................................................................. 2 Acknowledgments...................................................................................................................................................... -

Erie County Planning Department

Erie County Planning Department Act 167 County-Wide Watershed Stormwater Management Plan for Erie County Phase I – Scope of Study July 2008 200 West Kensinger Drive• Cranberry Township, Pennsylvania 16066 • 724.779.4777 [phone] TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 1 STORMWATER RUNOFF – ITS PROBLEMS AND ITS SOLUTIONS ...................................................... 1 PENNSYLVANIA STORMWATER MANAGEMENT ACT (ACT 167) .................................................. 1 ACT 167 PLANNING FOR ERIE COUNTY ........................................................................................ 2 BENEFITS OF THE PLAN ................................................................................................................... 2 APPROACH FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE STORMWATER MANAGEMENT PLAN ................. 3 THE NEED FOR A COMPREHENSIVE APPROACH FOR STORMWATER MANAGEMENT ...................................................................................... 4 PREVIOUS PLAN EFFORTS ............................................................................................................... 4 GENERAL COUNTY DESCRIPTION ........................................................................................................... 5 TRANSPORTATION .......................................................................................................................... 5 POLITICAL JURISDICTIONS ............................................................................................................ -

Under Development (PDF)

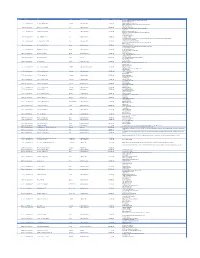

Project ID Category Title County Improvement Type Construction Cost Primary Project Description State Route 3009 (Linesville Road) Bridge over Bennett Run North Shenango Township 497 Under Development SR 3009 Brdg/Bennett Run Crawford Bridge Rehabilitation 500000 null Bridge Rehabilitation/Restoration Malbett Place (Township Road 690) Bridge over Twelve Mile Creek Harborcreek Township 852 Under Development Malbett Place (T-690) Brg Erie Bridge Replacement 873000 null Local Bridge Replacement State Route 6 (Columbus Avenue) Bridge over Hare Creek City of Corry 995 Under Development Columbus Ave,Corry Brdg Erie Bridge Rehabilitation 200000 null Bridge Rehabilitation/Restoration Depot Street (Township Road 628) Bridge over Seven Mile Creek Harborcreek Township Local Bridge Replacement 1023 Under Development Depot St-T628 7 Mile Ck Erie Bridge Replacement 270000 null project was canceled Union-LeBoeuf Road (Township Road 672) Bridge over South Branch French Creek 1000 feet south of State Route 97 Union and Le Boeuf Townships 1036 Under Development Union-LeBoeuf (T-672) Brdg Erie Bridge Rehabilitation 140000 null Local Bridge Restoration/Rehabilitation West County Line Road (Township Road 301) Bridge over Sugar Run Greene Township 1669 Under Development W. Co. Line Rd (T-301) Br Mercer Bridge Replacement 650000 null Local Bridge Replacement Old Mercer Road (Township Road 401) Bridge over Neshannock Creek East Lackawannock Township 1670 Under Development Old Mercer Rd (T-401) Br Mercer Bridge Replacement 1420000 null Local Bridge Replacement Service Avenue Bridge over Pine Run City of Sharon 1884 Under Development Service Avenue Bridge Mercer Bridge Replacement 500000 null Local Bridge Replacement SR 1001 in Lockport to near Queens Run Woodward Township 3850 Under Development SR 1001 Improvements Clinton Reconstruct 6926435 null Safety Improvement Widen add lane Resurface SR 75 over Hunters Creek Turbett Township 4189 Under Development PA 75 Hunter's Ck. -

Erie County Greenways

NORTHWEST PENNSYLVANIA GREENWAYS Erie County, Pennsylvania DCNR Project No. BRC-12.5.2 Pashek Associates February 8, 2010 Amended by Erie County Planning Department Introduction What is a Greenway? 2 Why a Greenways Plan for Erie County? 2 How was the Greenways Plan Developed? 3 Three-Step Process 3 Public Participation 3 Purpose of the Greenways Plan 3 Goals and Objectives 4 Chapter One – Where are we now? Gathering the Data 6 Existing Plans, Studies, and Other Planning Efforts 6 Erie County Comprehensive Plan (2003) 6 Erie County Natural Heritage Inventory (1993) 7 Erie County Greenways and Trails Plan (2000) 8 Pennsylvania Statewide Greenway Plan (2001) 8 Trail Feasibility Studies 9 Watershed Management Plans / Water Quality Studies 10 Miscellaneous Plans 12 Municipal Comprehensive Plans and Other Land Use Tools 13 Statewide Recreation Planning: Keystone Active Zone 15 Natural and Ecological Infrastructure Inventories 16 Natural Infrastructure Inventory Map 17 Ecological Infrastructure Inventory Map 18 Erie County Natural Heritage Inventory Sites 19 Descriptions of Natural and Ecological Inventory Elements 21 Gray Infrastructure 29 Inactive Rail Lines 29 Highway Bike Lanes 30 Shared Use Paths 30 Park and Ride Lots 30 Bus, Train, and Water Taxi Terminals 31 Canals 31 Erie County Greenways Plan Recreational Opportunities Inventory 31 State Parks and Facilities 31 Community and Neighborhood Parks 32 Private Parks and Recreational Facilities 33 Campgrounds 33 Bikeways and Pedestrian Paths 33 Waterfront Access Areas 33 Fishing Opportunities -

2021-02-02 010515__2021 Stocking Schedule All.Pdf

Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission 2021 Trout Stocking Schedule (as of 2/1/2021, visit fishandboat.com/stocking for changes) County Water Sec Stocking Date BRK BRO RB GD Meeting Place Mtg Time Upper Limit Lower Limit Adams Bermudian Creek 2 4/6/2021 X X Fairfield PO - SR 116 10:00 CRANBERRY ROAD BRIDGE (SR1014) Wierman's Mill Road Bridge (SR 1009) Adams Bermudian Creek 2 3/15/2021 X X X York Springs Fire Company Community Center 10:00 CRANBERRY ROAD BRIDGE (SR1014) Wierman's Mill Road Bridge (SR 1009) Adams Bermudian Creek 4 3/15/2021 X X York Springs Fire Company Community Center 10:00 GREENBRIAR ROAD BRIDGE (T-619) SR 94 BRIDGE (SR0094) Adams Conewago Creek 3 4/22/2021 X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 SR0234 BRDG AT ARENDTSVILLE 200 M DNS RUSSELL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) Adams Conewago Creek 3 2/27/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 SR0234 BRDG AT ARENDTSVILLE 200 M DNS RUSSELL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) Adams Conewago Creek 4 4/22/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 4 10/6/2021 X X Letterkenny Reservoir 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 4 2/27/2021 X X X Adams Co. National Bank-Arendtsville 10:00 200 M DNS RUSSEL TAVERN RD BRDG (T-340) RT 34 BRDG (SR0034) Adams Conewago Creek 5 4/22/2021 X X Adams Co. -

4204922608Mcp

THE BOROUGH OF EDINBORO COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 1997 Prepared by the BOROUGH OF EDINBORO Assisted by GRANEY, GROSSMAN, RAY AND ASSOCIATES New Wilmington, Pennsylvania Franklin, Pennsylvania This document was financed, in part, from the Small Communities Planning Assistance Program of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, as administered by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Community and Economic Development. Clifford E. Allen Caroline Rhodes, Deputy Mayor Edinboro Borouyh Cou ncil Jean A. Davis Charles F. Brand George Finney Richard Forcucci Mary Ann Horne Borough Manager Michael Hoy Borouyh Secretary Jan Gardner BorouPh Planninp and ZoninP Commission Ruth Cogan, Chairperson I Me1 Daughenbaugh, Vice Chairman Charles F. Brand A1 Dor6 I Fred Langill A. J. Manafo" I "Resigned 1/8/96 Zoniny Officer David Zamierowski Graney, Grossman, Ray and Associates New Wilmington, Pennsylvania Franklin, Pennsylvania I I TABLE OF CONTENTS I I Background Analysis Community Facilities .......................................... CF-1 Borough Government ....................................... CF-1 I The Community Building ..................................... CF-4 Public Works ............................................. CF-4 Water System ............................................ CF-6 I Sanitary Sewer System ....................................... CF-8 Storm Drainage .......................................... CF-10 I Refuse Collection ......................................... CF- 11 Police Service .......................................... -

Download Proposed Regulation

huts g4.i I 4 i r INDEPENDENTREGULA TORY RegulaLory na.ysis rOrm REVIEWCOMMISSION (Completed by Promulgating Agency) RECEIVED (All Camments submitted on this regulation will appear on IRRCs websfte) IRRC (1) Agency Environmental Protection ZOfl OCT —b 2 2: 29 (2) Agency Number: IRRC Number: Identification Number: 7-534 i (3) PA Code Cite: 25 Pa. Code, Chapter 93 (4) Short Title: Water Quality Standards — Triennial Review (5) Agency Contacts (List Telephone Number and Email Address): Primary Contact: Laura Edinger; 717.783.8727; ledingerpa.gov Secondary Contact: Jessica Shirley; 717.783.8727; jesshirleypa.gov (6) Typc of Rulemaking (check applicable box): Proposed Regulation D Emergency Certification Regulation; D Final Regulation D Certification by the Governor D Final Omitted Regulation D Certification by the Attorney General (7) Briefly explain the regulation in clear and nontechnical language. (100 words or less) Section 303(c)(l) of The Clean Water Act requires that states periodically, but at least once every 3 years, review and revise as necessary, their water quality standards. Further, states are required to protect existing uses of their waters. This regulation is undertaken as part of the Department’s ongoing review of Pennsylvania’s water quality standards. The proposed regulation will update and revise Table 3, at Section 93.7 by updating the aquatic life criterion for ammonia, and the Bacteria criteria for changes to the recreational use (Baci) criterion and moving the Bac2 criterion to Drainage List X; deleting reference to Appendix A, Table IA in Section 93.8a(b) since Table 1A is being deleted in Chapter 16; removing reference to the Federal regulation in 40 CFR 131.32(a) in Section 93.8a(j)(3) since this federal promulgation had been withdrawn by U.S. -

Final Report Application of Geographical Information System

Final Report Application of Geographical Information System Technology to Fish Conservation in Pennsylvania Phase I ORIGINAL: 1975 MIZNER COPIES: Wilmarth Org. in file June 1,1998 revised October 1,1998 Submitted to: Mr. Frank H. Felbaum, Executive Director Wild Resource Conservation Board P.O. Box 8764, Room 309 3rd &Reily Streets Harrisburg, PA 17120 Mr. Andrew Shiels Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission 450 Robinson Lane Bellefonte, PA 16823-9620 Prepared by: Mr. David G Argent Dr. Robert F. Carline Dr. Jay R Stauffer, Jr. Pennsylvania Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit The School of Forest Resources The Pennsylvania State University 113 Meride Laboratory University Park, PA 16802 (814)865-4511 Table of Contents Table of Contents... 1 List of Figures 2 List of Tables 3 Introduction 4 Methods 9 Results 13 Recommended Endangered fishes 14 Recommended Threatened fishes 29 Recommended Candidate fishes 35 Fishes Believed Extirpated 40 Questionable Pennsylvania fishes with limited distributions 41 Fishes Believed Secure 44 Streams and Rivers with rare fishes 45 Discussion 48 Recommendations 49 Literature cited 52 Appendices 58 Index of Maps 144 List of Figures 1. Pennsylvania's delineated watershed 12 2. Distribution of endangered fishes 16 3. Distribution of threatened fishes 30 4. Distribution of candidate fishes 36 5. Graph depicting Pennsylvania's proposed endangered, threatened, and candidate fishes by family 50 6. Pennsylvania watersheds that harbor proposed endangered, threatened, and candidate fishes 51 List of Tables 1. Current (as of January 1, 1998) and proposed endangered, threatened, and candidate fishes 5 2. Databases used to construct this report 11 3. Fishes that are considered extirpated from Pennsylvania 15 4.