Connecting After Killing : an Exploration of the Intersubjective Space Between Therapist and Client When Combat Rests Between Them

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/65f2825x Author Young, Mark Thomas Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Mark Thomas Young June 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Chairperson Dr. Steven Gould Axelrod Dr. Tom Lutz Copyright by Mark Thomas Young 2015 The Dissertation of Mark Thomas Young is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As there are many midwives to an “individual” success, I’d like to thank the various mentors, colleagues, organizations, friends, and family members who have supported me through the stages of conception, drafting, revision, and completion of this project. Perhaps the most important influences on my early thinking about this topic came from Paweł Frelik and Larry McCaffery, with whom I shared a rousing desert hike in the foothills of Borrego Springs. After an evening of food, drink, and lively exchange, I had the long-overdue epiphany to channel my training in musical performance more directly into my academic pursuits. The early support, friendship, and collegiality of these two had a tremendously positive effect on the arc of my scholarship; knowing they believed in the project helped me pencil its first sketchy contours—and ultimately see it through to the end. -

Examining the Therapist's Internal Experience When a Patient Dissociates in Session

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Doctorate in Social Work (DSW) Dissertations School of Social Policy and Practice Spring 5-13-2013 Do You Know What I Know? Examining the Therapist's Internal Experience when a Patient Dissociates in Session Jacqueline R. Strait University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations_sp2 Part of the Psychology Commons, and the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Strait, Jacqueline R., "Do You Know What I Know? Examining the Therapist's Internal Experience when a Patient Dissociates in Session" (2013). Doctorate in Social Work (DSW) Dissertations. 36. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations_sp2/36 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations_sp2/36 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Do You Know What I Know? Examining the Therapist's Internal Experience when a Patient Dissociates in Session Abstract There is rich theoretical literature that cites the importance of the therapist’s use of self as a way of knowing, especially in cases where a patient has been severely traumatized in early life. There is limited empirical research that explores the in-session experience of therapists working with traumatized patients in order to support these claims. This study employed a qualitative design to explore a therapist’s internal experience when a patient dissociates in session. The aim of this study was to further develop the theoretical construct of dissociative attunement to explain the way that therapist and patient engage in a nonverbal process of synchronicity that has the potential to communicate dissociated images, affect or somatosensory experiences by way of the therapist’s internal experience. -

ENDER's GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third

ENDER'S GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third "I've watched through his eyes, I've listened through his ears, and tell you he's the one. Or at least as close as we're going to get." "That's what you said about the brother." "The brother tested out impossible. For other reasons. Nothing to do with his ability." "Same with the sister. And there are doubts about him. He's too malleable. Too willing to submerge himself in someone else's will." "Not if the other person is his enemy." "So what do we do? Surround him with enemies all the time?" "If we have to." "I thought you said you liked this kid." "If the buggers get him, they'll make me look like his favorite uncle." "All right. We're saving the world, after all. Take him." *** The monitor lady smiled very nicely and tousled his hair and said, "Andrew, I suppose by now you're just absolutely sick of having that horrid monitor. Well, I have good news for you. That monitor is going to come out today. We're going to just take it right out, and it won't hurt a bit." Ender nodded. It was a lie, of course, that it wouldn't hurt a bit. But since adults always said it when it was going to hurt, he could count on that statement as an accurate prediction of the future. Sometimes lies were more dependable than the truth. "So if you'll just come over here, Andrew, just sit right up here on the examining table. -

In the Court of Criminal Appeals of Texas

IN THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS OF TEXAS NO. AP-76,580 ALBERT JAMES TURNER, Appellant v. THE STATE OF TEXAS ON DIRECT APPEAL FROM CAUSE NO.10-DCR-054233 IN THE 268TH DISTRICT COURT FORT BEND COUNTY KELLER, P.J., delivered the opinion of the Court in which KEASLER, HERVEY, ALCALA, RICHARDSON, YEARY and WALKER., JJ., joined. KEEL., J., dissented. NEWELL, J., did not participate. Appellant was convicted of capital murder for killing his wife and mother-in-law during the same criminal transaction.1 The jury answered the special issues in such a manner that Appellant 1 TEX. PENAL CODE §19.03(a)(7)(A); TEX. CODE CRIM. PROC. art. 37.071. Unless otherwise indicated, all future references to articles refer to the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure. TURNER – 2 was sentenced to death.2 Direct appeal to this Court is automatic.3 On original submission, we remanded this case for a retrospective competency hearing. We later ordered supplemental briefing on the effect, if any, of the Supreme Court’s recent decision in McCoy v. Louisiana.4 We now conclude that Appellant was competent to stand trial, but we also conclude that defense counsel conceded Appellant’s guilt of murder against Appellant’s wishes in violation of McCoy. Consequently, we reverse the trial court’s judgment of conviction and remand the case for a new trial. I. Background The day after Christmas of 2009, Appellant entered the home of his in-laws and killed his wife, Keitha Turner, and his mother-in-law, Betty Jo Frank, by cutting their throats. -

FC··O~· Fr·.J.. C····0'"P:Y

·~f\MW·r·;; .;~FC· ·O~· f\?:'*"=.4 h/\/)*:'U't$" .'~ fR·k ...J... c····0'".... .....p:y..... VV~ f\hdk ., ·wi ,...•... I ':Pj'~ p In T' (Ie (" ?~·I f l F! ;\ S-:. ~ ,,:--..,'1:;\;1.0'.';" •.-:- cr)"~~ ••• " r.. ) J"',. J.~ ..;':'''1'';\~), .{ TP,':'.,.. ;,.~.;: ~""{ ·:.r7f\R·-./ ' ,:..N' ,t~ ",~ PF{)PLE OF "lTfU STATE OF C,ALIFOR?'--HA, j t--Jo. 3083904 ) ) APFELLANT'S ~,, , } OPENING HIUEF f'-..j;~ "I"'I'j' ,;!iN,;',\/eR'[~'l ::("("! ,", .~ ''\. .... 'S.d. Y ,[,~" J./ J ;. :; ) ) I)tfendanjj\ppellant. ) .. ~ '..""'.' '~~ ~" · ·.·.· __ v.·.········ ·.·.'.' '.~ "] i\PPE/\L FR(}\4 TIlE JIJDG\JENT (n:' 'fEE SLiPEJUOR (,(}l.,iF:.T OF TIfE S'rATE OF C,Al,IFORNIA ,;,?>.,rcr~r .j';::';; 'Y';('V lNT'V ,'I ..{);::.:;:" ,,/ .,"U ''; "H,.d,., :,>:,J C' ,,~,':i :.! J Sl.JPEHJOR, (:OURT' C/\SFNO, £3AJ0562.2,,01 ,nj'~j'" TU'C. n.L, ..'I 'l,rC}N(}n::. '" l:\":'d?L.0.•!S nr D C"'·l.. ,Jrl>'j"'j''''·B'... ,~ ., , I'{,'\.l : ::"'~)·j1'['JCn.::.·,·'x" LJ\\VOF'Fl:CES OF J(:JUt'..; P, S('EL:(]( John F. SdHl{;k~ ih,}(i J 11 JJl'~;'~ lj ". ,". <., .... - 'fro),.eo ~.,~U)'-"'Y'(l'l'.l...">:~}~.,I'. t. Si''-'''''·........ tv'V':."" ....t;;,:,...'~";.t;-,,..·':.·w .L..~ Falo AJto, C/\ 94303 1(50) 856,7963 '\ H;'r'"''{-'v .!",~, l"p,;' ~- ... ':.;;, ... : s.~"A'./ _.'I'•.•.s,,:.. .....;\ .j'w,,</t·· ....:... ~.'~· .. s~·~. NA,. 'II L:\N \JEPJ)Uf';() (,;\pjx>inted by the ('<>w":.\ SUPREME COURT, STATE OF CALIFORNIA PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA, ) No. S083904 ) Plaintiff/Respondent, ) ) APPELLANT'S v. ) OPENING BRIEF ) NATHAN VERDUGO, ) ) Defendant!Appellant. ) --------------- ) APPEAL FROM THE JUDGMENT OF THE SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES COUNTY SUPERIOR COURT CASE NO. -

In the District Court of Appeal

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA ROBERT EARL PETERSON, Appellant, v. CASE NO. SC10-274 STATE OF FLORIDA, Appellee. / ON APPEAL FROM THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE FOURTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT, IN AND FOR DUVAL COUNTY, FLORIDA INITIAL BRIEF OF APPELLANT NANCY A. DANIELS PUBLIC DEFENDER SECOND JUDICIAL CIRCUIT DAVID A. DAVIS ASSISTANT PUBLIC DEFENDER FLORIDA BAR NO. 271543 301 S. MONROE ST., SUITE 401 TALLAHASSEE, FLORIDA 32301 (850) 606-8517 ATTORNEY FOR APPELLANT TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................... i TABLE OF CITATIONS ......................................................................................... ii I. PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .................................................................... 1 II. STATEMENT OF THE CASE ...................................................................... 2 III. STATEMENT OF THE FACTS .................................................................... 5 IV. SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ........................................................... 12 V. ARGUMENT ISSUE I: THE COURT FUNDAMENTALLY ERRED WHEN IT ALLOWED THE STATE TO REPEATEDLY PRESENT EVIDENCE THAT PETERSON MAY HAVE COMMITTED ANOTHER MURDER, A VIOLATION OF THE DEFENDANT’S FIFTH, SIXTH, EIGHTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT RIGHTS TO A FAIR TRIAL AND SENTENCE. ................................................................ 16 ISSUE II: THE COURT ERRED IN ALLOWING THE STATE TO PRESENT, AS ITS ONLY PENALTY PHASE EVIDENCE, SEVERAL VICTIM IMPACT STATEMENTS IN VIOLATION -

River City Memoirs VII River Citydave Memoirs Engel Ghost Ghost of Myself

Dave Engel Ghost of Myself River City Memoirs VII River CityDave Memoirs Engel Ghost Ghost of Myself River City Memoirs VII1 Ghost River City Memoirs iver City Memoirs VII: Ghost of Myself is a collection of stories previously pub- Rlished in the Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tri- bune 1998-2008. This limited edition is available only to supporters of the South Wood County His- torical Corp. publication fund. ommendation to : Phil Brown, SWCHC; Lori Brost, SWCHC; Kathy Engel, CMSPT; Allen Hicks, Daily Tribune; Holly (Pearl) Knoll, assistant editor; Daniel P. Meyer, patron saint; Warren Miller, Print Shop. emo: no entity other than the Wiscon- sin Rapids Daily Tribune is autho- Mrized to scan, copy, reprint or transmit material from this volume without the expressed, written permission of River City Memoirs. River City Memoirs 2009 5597 Third Avenue ©Rudolph WI 54475 You’re either part of the solution or part of the problem. Eldridge Cleaver (1935-1998) 2 From the first River City Memoirs 1983 River City Memoirs Ghost he title “River City Memoirs,” But so much for the English major In a typical sendup of the fads of comes from the history major I side of life. For History, I took a look at youth, the 1959 Tribune lampooned a almost was at Point college the 1959 Tribune (fifty years ago), and cultural phenomenon we now know Tand to the 80 per cent of readers who sampled references that are part of the presaged the collapse of conventional prefer me that way: the gray-bearded, disappeared world the ghosts of my gen- moral values. -

Six Minutes Brennen Carl Brunner Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1996 Six minutes Brennen Carl Brunner Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Brunner, Brennen Carl, "Six minutes " (1996). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 7080. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/7080 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Six Minutes by Brennen Carl Brunner A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: English Major: Creative Writing Major Professor: Steven Pett Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1996 CHAPTER 1: STAND UP I ran again this afternoon after school, after my mother took me aside to tell me she was pregnant. "Things will be different/' she told me as she gave me a hug. "But not that different." I ran further than I usually do on weekdays, to the highway outside of town, and picked it up on the way back. I'm nauseous now, walking with my arms over my head at the end of the driveway, when I hear the screech of brakes and a whimper behind me. I spin and see a dog trotting away from the postal truck in the middle of the street, turning his head around to eye it as the driver inside coughs hoarsely and rubs his forehead. -

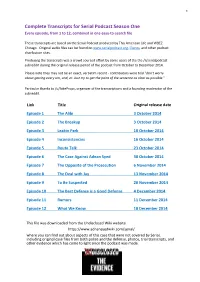

Serial Podcast Season One Every Episode, from 1 to 12, Combined in One Easy-To-Search File

1 Complete Transcripts for Serial Podcast Season One Every episode, from 1 to 12, combined in one easy-to-search file These transcripts are based on the Serial Podcast produced by This American Life and WBEZ Chicago. Original audio files can be found on www.serialpodcast.org, iTunes, and other podcast distribution sites. Producing the transcripts was a crowd sourced effort by some users of the the /r/serialpodcast subreddit during the original release period of the podcast from October to December 2014. Please note they may not be an exact, verbatim record - contributors were told "don't worry about getting every um, and, er. Just try to get the point of the sentence as clear as possible." Particular thanks to /u/JakeProps, organizer of the transcriptions and a founding moderator of the subreddit. Link Title Original release date Episode 1 The Alibi 3 October 2014 Episode 2 The Breakup 3 October 2014 Episode 3 Leakin Park 10 October 2014 Episode 4 Inconsistencies 16 October 2014 Episode 5 Route Talk 23 October 2014 Episode 6 The Case Against Adnan Syed 30 October 2014 Episode 7 The Opposite of the Prosecution 6 November 2014 Episode 8 The Deal with Jay 13 November 2014 Episode 9 To Be Suspected 20 November 2014 Episode 10 The Best Defense is a Good Defense 4 December 2014 Episode 11 Rumors 11 December 2014 Episode 12 What We Know 18 December 2014 This file was downloaded from the Undisclosed Wiki website https://www.adnansyedwiki.com/serial/ where you can find out about aspects of this case that were not covered by Serial, including original case files from both police and the defense, photos, trial transcripts, and other evidence which has come to light since the podcast was made. -

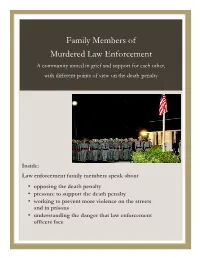

Family Members of Murdered Law Enforcement a Community United in Grief and Support for Each Other, with Different Points of View on the Death Penalty

12 Family Members of Murdered Law Enforcement A community united in grief and support for each other, with different points of view on the death penalty Inside: Law enforcement family members speak about • opposing the death penalty • pressure to support the death penalty • working to prevent more violence on the streets and in prisons • understanding the danger that law enforcement officers face ; Murder Victims’ Families for Human Rights Law Enforcement Family Members Kathy MVFHR Dillon For Victims, Against the Death Penalty Kathy Dillon has spoken out against the death penalty in several venues. She wrote in MVFHR’s Fall 2010 Murder Victims’ Families for newsletter: Human Rights In 1974, my father was 89 South St Suite 601 Boston MA 02111 shot and killed in the line 617-443-1102 of duty on the New York www.mvfhr.org State Thruway. He had been a New York State being sought, it bothered me. Trooper for 16 years. At I knew that an execution was Staff: that time, the death penalty not what I needed for my was an available sentence in healing. But there was really Renny Cushing, Executive New York for first-degree nobody to talk to at that time Director • Kate Lowenstein, murder of a police officer. I about those feelings. Program Director • Susannah learned many years later Sheffer, Project Director/Staff I think that my aversion Writer that the District Attorney had come to our house to to the idea of the death talk with my mother about penalty, back then, must have Board of Directors: it at least a couple of times been tied to my upbringing as after my father was a Catholic and the teachings Bud Welch, President • Jeanne murdered, virtually assuring of “thou shalt not kill.” At Bishop, Treasurer • Stanley her that this would be the that time, though, the Allridge • Rev. -

On Writing : a Memoir of the Craft / by Stephen King

l l SCRIBNER 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 Visit us on the World Wide Web http://www.SimonSays.com Copyright © 2000 by Stephen King All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. SCRIBNER and design are trademarks of Macmillan Library Reference USA, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, the publisher of this work. DESIGNED BY ERICH HOBBING Set in Garamond No. 3 Library of Congress Publication data is available King, Stephen, 1947– On writing : a memoir of the craft / by Stephen King. p. cm. 1. King, Stephen, 1947– 2. Authors, American—20th century—Biography. 3. King, Stephen, 1947—Authorship. 4. Horror tales—Authorship. 5. Authorship. I. Title. PS3561.I483 Z475 2000 813'.54—dc21 00-030105 [B] ISBN 0-7432-1153-7 Author’s Note Unless otherwise attributed, all prose examples, both good and evil, were composed by the author. Permissions There Is a Mountain words and music by Donovan Leitch. Copyright © 1967 by Donovan (Music) Ltd. Administered by Peer International Corporation. Copyright renewed. International copyright secured. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Granpa Was a Carpenter by John Prine © Walden Music, Inc. (ASCAP). All rights administered by WB Music Corp. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Warner Bros. Publications U.S. Inc., Miami, FL 33014. Honesty’s the best policy. —Miguel de Cervantes Liars prosper. —Anonymous First Foreword In the early nineties (it might have been 1992, but it’s hard to remember when you’re having a good time) I joined a rock- and-roll band composed mostly of writers. -

Suicide the Forever Decision by Dr. Paul G. Quinnett

SUICIDE The Forever Decision New 3rd Edition By Dr. Paul G. Quinnett Dr. Quinnett is a clinical psychologist and the Director of the QPR Institute, an educational organization dedicated to preventing suicide. He has worked with suicidal people and survivors of suicide for more than 35 years. Author of seven books and an award- winning journalist, he is also a Clinical Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science at the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, Washington. Compliments of the QPR Institute Suicide: the Forever Decision For those thinking about suicide and for those who know, love and counsel them. DISCLAIMER Both author and publisher wish the reader to know that this book does not offer mental health treatment, and in no way should be considered a substitute for consultation with a professional. The identities of the people written about in this book have been carefully disguised in accordance with professional standards of confidentiality and in keeping with their rights to privileged communication with the author. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Introduction ...........................................................................5 CHAPTER1 You Don't Have to Be Crazy...................................................7 CHAPTER2 An Idea That Kills ................................................................ 11 CHAPTER3 Don't I Have a Right to Die?................................................. 13 CHAPTER4 Are You Absolutely Sure?...................................................