Synthesizing Strategies of Denial in the Later Films of Atom Egoyan, 1994-2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS, FEATURE DOCUMENTARIES AND MADE-FOR-TELEVISION FILMS, 1945-2011 COMPILED BY PAUL GRATTON MAY, 2012 2 5.Fast Ones, The (Ivy League Killers) 1945 6.Il était une guerre (There Once Was a War)* 1.Père Chopin, Le 1960 1946 1.Canadians, The 1.Bush Pilot 2.Désoeuvrés, Les (The Mis-Works)# 1947 1961 1.Forteresse, La (Whispering City) 1.Aventures de Ti-Ken, Les* 2.Hired Gun, The (The Last Gunfighter) (The Devil’s Spawn) 1948 3.It Happened in Canada 1.Butler’s Night Off, The 4.Mask, The (Eyes of Hell) 2.Sins of the Fathers 5.Nikki, Wild Dog of the North 1949 6.One Plus One (Exploring the Kinsey Report)# 7.Wings of Chance (Kirby’s Gander) 1.Gros Bill, Le (The Grand Bill) 2. Homme et son péché, Un (A Man and His Sin) 1962 3.On ne triche pas avec la vie (You Can’t Cheat Life) 1.Big Red 2.Seul ou avec d’autres (Alone or With Others)# 1950 3.Ten Girls Ago 1.Curé du village (The Village Priest) 2.Forbidden Journey 1963 3.Inconnue de Montréal, L’ (Son Copain) (The Unknown 1.A tout prendre (Take It All) Montreal Woman) 2.Amanita Pestilens 4.Lumières de ma ville (Lights of My City) 3.Bitter Ash, The 5.Séraphin 4.Drylanders 1951 5.Have Figure, Will Travel# 6.Incredible Journey, The 1.Docteur Louise (Story of Dr.Louise) 7.Pour la suite du monde (So That the World Goes On)# 1952 8.Young Adventurers.The 1.Etienne Brûlé, gibier de potence (The Immortal 1964 Scoundrel) 1.Caressed (Sweet Substitute) 2.Petite Aurore, l’enfant martyre, La (Little Aurore’s 2.Chat dans -

The Nominees for Best Feature Length Drama

2012 LEO AWARDS NOMINEES & WINNERS BEST FEATURE LENGTH DRAMA WINNER Sisters&Brothers Carl Bessai, James Brown, Emily Alden - Producers NOMINEES Daydream Nation Christine Haebler, Trish Dolman - Producers Doppleganger Paul Katherine Hazon, Oliver Linsley, Dylan Akio Smith, Kris Elgstrand - Producers Marilyn Christopher Petry, Kaleena Kiff, Bruce Borland - Producers The Odds Simon Davidson, Kirsten Newlands, Oliver Linsley - Producers Page 1 of 78 2012 LEO AWARDS NOMINEES & WINNERS BEST DIRECTION FEATURE LENGTH DRAMA WINNER Carl Bessai Sisters&Brothers NOMINEES Dylan Akio Smith, Kris Elgstrand Doppleganger Paul Paul A. Kaufman Magic Beyond Words: The J.K. Rowling Story Christopher Petry Marilyn Simon Davidson The Odds Page 2 of 78 2012 LEO AWARDS NOMINEES & WINNERS BEST SCREENWRITING FEATURE LENGTH DRAMA WINNER Kris Elgstrand Doppleganger Paul NOMINEES Melodie Krieger, Jim Cliffe Donovan's Echo Christopher Petry Marilyn Aaron Houston Sunflower Hour Simon Davidson The Odds Page 3 of 78 2012 LEO AWARDS NOMINEES & WINNERS BEST CINEMATOGRAPHY FEATURE LENGTH DRAMA WINNER Jon Joffin Daydream Nation NOMINEES Michael C. Blundell Hamlet Pieter Stathis Hit 'n Strum Mathias Herndl Magic Beyond Words: The J.K. Rowling Story Norm Li The Odds Page 4 of 78 2012 LEO AWARDS NOMINEES & WINNERS BEST PICTURE EDITING FEATURE LENGTH DRAMA WINNER Sabrina Pitre Sisters&Brothers NOMINEES Jamie Alain Daydream Nation Mark Shearer Donovan's Echo Kirby Jinnah Marilyn Greg Ng Sunflower Hour Page 5 of 78 2012 LEO AWARDS NOMINEES & WINNERS BEST OVERALL SOUND FEATURE LENGTH -

Bruce Greenwood, Leslie Hope, Benjamin Ayres

Directed by Jerry Ciccoritti Written by Jeff Kober Starring: Bruce Greenwood, Leslie Hope, Benjamin Ayres, Megan Follows, David Hewlett, Kris Holden-Reid, Jeff Kober, Grace Lynn Kung, Kristin Lehman, Daniel Maslany, Tony Nappo, Paula Rivera TRT: 92:26 Format: 2:39 Sound: 5.1 surround sound Rating: (pending) Country: Canada Language: English Genre: Drama Trailers: Available Website: www.IndicanPictures.com Table of Contents Synopsis ...................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Director’s Statement .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Producer’s Statement ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Artist’s Statement (Jeff Kober) ................................................................................................................................... 4 Cast Bios ...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Bruce Greenwood (Frank) ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Leslie Hope (Melanie) ............................................................................................................................................ -

Collection Adultes Et Jeunesse

bibliothèque Marguerite Audoux collection DVD adultes et jeunesse [mise à jour avril 2015] FILMS Héritage / Hiam Abbass, réal. ABB L'iceberg / Bruno Romy, Fiona Gordon, Dominique Abel, réal., scénario ABE Garage / Lenny Abrahamson, réal ABR Jamais sans toi / Aluizio Abranches, réal. ABR Star Trek / J.J. Abrams, réal. ABR SUPER 8 / Jeffrey Jacob Abrams, réal. ABR Y a-t-il un pilote dans l'avion ? / Jim Abrahams, David Zucker, Jerry Zucker, réal., scénario ABR Omar / Hany Abu-Assad, réal. ABU Paradise now / Hany Abu-Assad, réal., scénario ABU Le dernier des fous / Laurent Achard, réal., scénario ACH Le hérisson / Mona Achache, réal., scénario ACH Everyone else / Maren Ade, réal., scénario ADE Bagdad café / Percy Adlon, réal., scénario ADL Bethléem / Yuval Adler, réal., scénario ADL New York Masala / Nikhil Advani, réal. ADV Argo / Ben Affleck, réal., act. AFF Gone baby gone / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF The town / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF L'âge heureux / Philippe Agostini, réal. AGO Le jardin des délices / Silvano Agosti, réal., scénario AGO La influencia / Pedro Aguilera, réal., scénario AGU Le Ciel de Suely / Karim Aïnouz, réal., scénario AIN Golden eighties / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Hotel Monterey / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Jeanne Dielman 23 quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE La captive / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Les rendez-vous d'Anna / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE News from home / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario, voix AKE De l'autre côté / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Head-on / Fatih Akin, réal, scénario AKI Julie en juillet / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI L'engrenage / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Solino / Fatih Akin, réal. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

It's a Conspiracy

IT’S A CONSPIRACY! As a Cautionary Remembrance of the JFK Assassination—A Survey of Films With A Paranoid Edge Dan Akira Nishimura with Don Malcolm The only culture to enlist the imagination and change the charac- der. As it snows, he walks the streets of the town that will be forever ter of Americans was the one we had been given by the movies… changed. The banker Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), a scrooge-like No movie star had the mind, courage or force to be national character, practically owns Bedford Falls. As he prepares to reshape leader… So the President nominated himself. He would fill the it in his own image, Potter doesn’t act alone. There’s also a board void. He would be the movie star come to life as President. of directors with identities shielded from the public (think MPAA). Who are these people? And what’s so wonderful about them? —Norman Mailer 3. Ace in the Hole (1951) resident John F. Kennedy was a movie fan. Ironically, one A former big city reporter of his favorites was The Manchurian Candidate (1962), lands a job for an Albu- directed by John Frankenheimer. With the president’s per- querque daily. Chuck Tatum mission, Frankenheimer was able to shoot scenes from (Kirk Douglas) is looking for Seven Days in May (1964) at the White House. Due to a ticket back to “the Apple.” Pthe events of November 1963, both films seem prescient. He thinks he’s found it when Was Lee Harvey Oswald a sleeper agent, a “Manchurian candidate?” Leo Mimosa (Richard Bene- Or was it a military coup as in the latter film? Or both? dict) is trapped in a cave Over the years, many films have dealt with political conspira- collapse. -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced. -

SALLI NEWMAN (818) 618‐1551 (C) * (818) 955‐5711 (O) PRODUCER [email protected] ______

SALLI NEWMAN (818) 618‐1551 (C) * (818) 955‐5711 (O) PRODUCER [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ FEATURE FILMS “THE MAGIC OF BELLE ISLE” — Producer (Summer 2012 release) Firebrand Productions/Summer Magic Productions/Castle Rock Entertainment/Magnolia Pictures/Revelations Entertainment Director: Rob Reiner * Cast: Morgan Freeman and Virginia Madsen * Location: Upstate New York “ANOTHER HAPPY DAY” — Producer Mandalay Vision Director: Sam Levinson * Cast: Ellen Barkin, Demi Moore, Kate Bosworth, Thomas Haden Church, Ellen Burstyn, George Kennedy, Jeffrey DeMunn, Ezra Miller * Location: Michigan * Sundance Winner of the Waldo Salt Screenwriting Award – Sam Levinson “DAVID & GOLIATH” (Short) — Production Consultant Zaver Productions/Filmmakers Alliance Director: George Zaver * Cast: Billy Burke * Location: Los Angeles * Winner of Various Film Festival Awards including Best Short Film and Best First Time Director “MY ONE AND ONLY” — Consulting Producer Herrick Entertainment Director: Richard Loncraine * Cast: Renee Zellweger, Kevin Bacon, Chris Noth, Logan Lerman * Locations: Baltimore; New Mexico “D2: THE MIGHTY DUCKS” — Co‐Producer Avnet‐Kerner Company/Walt Disney Pictures Director: Sam Weisman * Cast: Emilio Estevez, Joshua Jackson * Locations: Los Angeles; Minneapolis “WHEN A MAN LOVES A WOMAN” — Associate Producer Avnet‐Kerner Company/Touchstone Pictures Director: Luis Mandoki * Cast: Meg Ryan, Andy Garcia * Locations: -

![Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3954/inmedia-3-2013-%C2%AB-cinema-and-marketing-%C2%BB-online-online-since-22-april-2013-connection-on-22-september-2020-603954.webp)

Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 3 | 2013 Cinema and Marketing Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.524 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference InMedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online since 22 April 2013, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ inmedia.524 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © InMedia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cinema and Marketing When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Nathalie Dupont and Joël Augros Jerry Pickman: “The Picture Worked.” Reminiscences of a Hollywood publicist Sheldon Hall “To prevent the present heat from dissipating”: Stanley Kubrick and the Marketing of Dr. Strangelove (1964) Peter Krämer Targeting American Women: Movie Marketing, Genre History, and the Hollywood Women- in-Danger Film Richard Nowell Marketing Films to the American Conservative Christians: The Case of The Chronicles of Narnia Nathalie Dupont “Paris . As You’ve Never Seen It Before!!!”: The Promotion of Hollywood Foreign Productions in the Postwar Era Daniel Steinhart The Multiple Facets of Enter the Dragon (Robert Clouse, 1973) Pierre-François Peirano Woody Allen’s French Marketing: Everyone Says Je l’aime, Or Do They? Frédérique Brisset Varia Images of the Protestants in Northern Ireland: A Cinematic Deficit or an Exclusive -

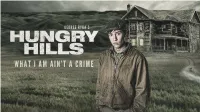

Hungry-Hills-EPK-Final-Compressed.Pdf

Language: English Genre: Drama Runtime: 92 minutes Country of Origin: Canada Short Synopsis Returning to live with his traumatized aunt after two years in a home for boys, Snit Mandolin (15) soon joins up with Johnny Swift(16) to make moonshine in the hills. When Snit meets Roy Kane the present collides with the past and the boys are taken to a violent crossroads. Long Synopsis Saskatchewan, 1954. After two years in a home for boys, SNIT MANDOLIN, 15, goes to stay with MATILDA, his aunt, who lives an impoverished and isolated life in the hills. Snit tries to make a place for himself in the only home he's ever known but the meanness of poverty and the harshness of the land defeat him. The community that still shuns his family - and paid to have Snit taken away - has not changed. Snit falls in with another outsider, JOHNNY SWIFT,16. Johnny makes moonshine and sells it through a local bootlegger. The boys become fast friends until their adventure is cut short by ROY KANE, the district's private cop. Enigmatic, unpredictable, and with his own sense of justice, Kane is after the bootlegger and will use the boys to get to him. It was Kane who dragged Snit away from his home those years ago. As he plays cat-and-mouse with the boys, Kane begins to wonder about the place he warehoused Snit in, and what it might have done to Snit. Dogged by Kane and betrayed by the bootlegger, Snit and Johnny arrive at a violent crossroads. -

Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema's Representation of Non

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] University of Southampton Faculty of Arts and Humanities Film Studies Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. DOI: by Eliot W. Blades Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2020 University of Southampton Abstract Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Film Studies Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. by Eliot W. Blades This thesis examines a number of mainstream fiction feature films which incorporate imagery from non-cinematic moving image technologies. The period examined ranges from the era of the widespread success of television (i.e.