South Dakota Elder Abuse Task Force

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

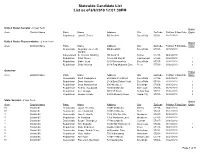

Statewide Candidate List List As of 6/9/2010 12:01:38PM

Statewide Candidate List List as of 6/9/2010 12:01:38PM United States Senator - 6 Year Term Ballot Area District Name Party Name Address City ZipCode Petition Filing Date Order Republican John R. Thune PO Box 841 Sioux Falls 57101- 03/17/2010 United States Representative - 2 Year Term Ballot Area District Name Party Name Address City ZipCode Petition Filing Date Order Democratic Stephanie Herseth PO Box 2009 Sioux Falls 57101- 03/17/2010 Sandlin Independent B. Thomas Marking PO Box 219 Custer 57730- 04/29/2010 Republican Kristi Noem 18575 US Hwy 81 Castlewood 57223- 03/23/2010 1 Republican Blake Curd 38 S Riverview Hts Sioux Falls 57105- 03/27/2010 2 Republican Chris Nelson 2104 Flag Mountain Drive Pierre 57501- 03/02/2010 3 Governor Ballot Area District Name Party Name Address City ZipCode Petition Filing Date Order Democratic Scott Heidepriem 503 East 21st Street Sioux Falls 57105- 03/04/2010 Republican Dave Knudson 2100 East Slaten Court Sioux Falls 57103- 03/31/2010 1 Republican Scott Munsterman 306 4th Street Brookings 57006- 03/30/2010 2 Republican Dennis Daugaard 24930 480th Ave Garretson 57030- 03/15/2010 3 Republican Ken Knuppe HCR 57 Box A Buffalo Gap 57722- 03/26/2010 4 Republican Gordon Howie 23415 Bradsky Road Rapid City 57703- 03/30/2010 5 State Senator - 2 Year Term Ballot Area District Name Party Name Address City ZipCode Petition Filing Date Order 01 District 01 Democratic Jason Frerichs 13497 465th Ave Wilmot 57279- 03/02/2010 02 District 02 Democratic Jim Hundstad 13755 395th Ave Bath 57427- 03/12/2010 3 District 03 Democratic Alan C. -

2012 Primary Election

State Senator - 02 - REP (South Dakota) 2012 Primary Election - OFFICIAL RESULTS Brown County Precinct Art Fryslie Norbert Barrie TOTALS Courthouse Community Rm #8 (Courthouse Community Room ) 11 25 36 Columbia American Legion (Columbia American Legion ) 11 20 31 School/Blind & Visually Imp #16 (School for Blind & Visually Impaired) 13 14 27 Warner Community Center (Warner Community Center) 17 36 53 Stratford Community Center (Stratford Communty Center) 7 12 19 Groton Community Center (Groton Community Center) 16 64 80 Claremont Fire Station (Claremont Fire Station) 1 9 10 TOTAL 76 180 256 State Senator - 02 - REP (South Dakota) 2012 Primary Election - OFFICIAL RESULTS Clark County Precinct Art Fryslie Norbert Barrie TOTALS Blaine, Cottonwood, Sp Val, War (Bradley Community Center) 10 6 16 Ash, Woodland, Garfield, Elrod (Clark County Courthouse) 14 2 16 Raymond Twp, Logan, Fordham, To (Raymond Fire Hall) 15 3 18 Thorp, Maydell, Eden, Town of G (Prairie Ridge Lodge ) 14 2 16 Mt Pleasant, Day, Darlington (Clark County Courthouse) 2 3 5 Foxton, Merton, Town of (Clark County Courthouse) 15 4 19 Lake, Washington, Collins (Willow Lake Grace Lutheran Church) 21 2 23 Town of Willow Lake (Willow Lake Community Center) 27 9 36 Town of Vienna, Pleasant (Vienna Town Hall) 35 4 39 Richland, Hague, Rosedale (Carpenter Community Center) 11 0 11 City of Clark Ward I (Clark Senior Citizens - Ullyot Bldg ) 28 4 32 City of Clark Ward II (Clark Senior Citizens - Ullyot Bldg ) 30 10 40 City of Clark Ward III, Lincoln (Clark Senior Citizens - Ullyot Bldg ) -

Feb 16 Cover Cvr.Qxd

Official Monthly Publication Member of National League of Cities Contents Features www.sdmunicipalleague.org 2015 Municipal Annual Report Forms . .6 2016 Legislative Information . .6-11 South Dakota SDMEA Superintendent & Foreman Conference . .12 MUNICIPALITIES 2016 District Meetings Schedule . .13 Managing Editor: Yvonne A. Taylor Editor: Carrie A. Harer SD Police Chiefs Accepting Award Nominations . .14 PRESIDENT DISTRICT CHAIRS SD Building Officials Seminar . .15 Meri Jo Anderson Dist. 1 - Mike Grosek Finance Officer, Mayor, Webster Code Officer of the Year Nomination Form . .16 New Underwood Dist. 2 - Tim Reed Scholarship Funds Available . .17 1st VICE PRESIDENT Mayor, Brookings Laurie Gill SD Transportation Alternatives Program . .18 Mayor, Pierre Dist. 3 - Amy Nelson City Manager, Yankton Building Relationships at District Meetings . .19 2nd VICE PRESIDENT Mike Wendland Dist. 4 - Debbie Houseman Important 2015 Tax Information Mayor, Baltic Finance Officer, Lake Andes Form 1095-B (Health Coverage) . .20 TRUSTEES Dist. 5 - Renae Phinney Gov. Daugaard Awards Four Community Pauline Sumption President, Ree Heights Finance Officer, Rapid City Development Block Grants . .21 Dist. 6 - Mike Hammrich Greg Jamison Councilmember, Ipswich How Cold Is Too Cold? Problems for Storage Tanks . .22 Councilmember, Sioux Falls Dist. 7 - Arnold Schott When It Doesn’t Surface . .24 Karl Alberts Mayor, McLaughlin Finance Officer, Aberdeen Using Social Media Effectively . .26 Dist. 8 - Harry Weller Steve Allender, Mayor, Kadoka Fixing Sign Codes after Reed: All Is Not Lost . .28 Mayor, Rapid City Dist. 9 - Carolynn Anderson Engaging Residents as Volunteers . .30 Anita Lowary Finance Officer, Wall Finance Officer, Groton Growing Public Servants . .34 Dist. 10 - Fay Bueno PAST PRESIDENT Finance Officer, Sturgis State Historical Society Awards Grants . -

South Dakota 2015 Gas Tax Increase (SB 1)

South Dakota Senate Bill 1 (2015) Title of Bill: Senate Bill 1 Purpose: Revise certain taxes and fees to: fund improvements to public roads and bridges in South Dakota, to increase the maximum speed limit on interstate highways, and to declare an emergency. i Status of Amendment: Passed South Dakota Senate Bill 1 (2015) Signed into law: March 30, 2015 Senate House FOR 25 55 AGAINST 8 11 History State Gas Tax The state gas tax on gasoline and diesel for highway use has not been increase since 1999, when Bill Janklow (R) was governor. Subsequent governors Mike Rounds and Dennis Daugaard were both vocally opposed to highway-tax increases, until Dauggard changed his position in the beginning of 2015. ii Gas Tax Distribution & Transportation Funding Sources Most of the funds generated by SB 1 will go towards state work, but some will go into a local bridge fund managed by the state Transportation Commission. The gas tax increase will produce an estimated $40.5 million and the excise tax an additional $27 million to $30 million. Additionally the license plate increases are expected to generate $18 million for counties, their share depending on the number of vehicles registered there. ii Need South Dakota, like many states, is struggling to maintain funding for their transportation system. Roads-Currently, South Dakota’s state roads are considered to be in good conditions, with only 2 percent rated “poor” and 9 percent rated “fair.” By 2024 though, the state Department of Transportation predicts that 25 percent of roads will be “poor” and 27 percent “fair.” For local governments the current situation is more urgent. -

District Title Name Party Affiliation Home Address City State Zip Phone Other Phone Email Legislative Email 1 Rep

District Title Name Party Affiliation Home Address City State Zip Phone Other Phone Email Legislative email 1 Rep. Susan Wismer Democrat PO Box 147 Britton SD 57430 605-448-5189 605-237-3086 [email protected] [email protected] 1 Rep. Dennis Feickert Democrat 38485 129th Street Aberdeen SD 57401 605-225-5844 [email protected] [email protected] 2 Rep. Brock L. Greenfield Republican 507 N Smith Street Clark SD 57225 605-532-4088 605-532-3799 [email protected] [email protected] 2 Rep. Burt E. Tulson Republican 44975 SD Highway 28 Lake Norden SD 57428 605-785-3480 605-881-7809 [email protected] 3 Rep. David Novstrup Republican 1008 S Wells Street Aberdeen SD 57401 605-380-9998 605-225-8541 [email protected] [email protected] 3 Rep. Dan Kaiser Republican 1415 Nicklaus Drive Aberdeen SD 57401 605-228-4988 605-626-7737 [email protected] 4 Rep. Kathy Tyler Democrat 48170 144th Street Big Stone SD 57216 605-432-4310 605-237-0228 [email protected] [email protected] 4 Rep. Jim Peterson Democrat 16952 482nd Avenue Revillo SD 57259 605-623-4573 [email protected] [email protected] 5 Rep. Melissa Magstadt Republican 1625 Northridge Dr. Unit 107 Watertown SD 57201 605-753-6205 [email protected] [email protected] 5 Rep. Roger Solum Republican 1333 Mayfair Drive Watertown SD 57201 605-882-7056 605-882-5284 [email protected] [email protected] 6 Rep. -

Region 7B Champs Four South Dakotans with Distinguished Newspaper Careers Will Be Inducted Into the South Dakota Newspaper Hall of Fame in April

Number 10 • Volume 111 March 10, 2016 Newspaper Hall of Fame to honor four South Dakotans Region 7B Champs Four South Dakotans with distinguished newspaper careers will be inducted into the South Dakota Newspaper Hall of Fame in April. They are: Jim Moritz of the Faulk County Record, Kathy Nelson of the Timber Lake Topic, Timothy Waltner of the Freeman Courier, and the late Kenneth B. Way of the Watertown Public Opinion. The four newspaper people will be honored during the South Dakota Newspaper Association annual convention April 29 in Mitchell. Plaques honoring members of the Newspaper Hall of Fame are dis - played at the Anson & Ada May Yeager Hall at South Dakota State Uni - versity. The SDSU Department of Journalism and Mass Communica - tions has been home to the Newspaper Hall of Fame ever since the Hall of Fame was established in 1934. "We are humbled to honor those who have made significant contribu - tions to the newspaper industry in our state," said SDNA President Bill Krikac, publisher of the Clark County Courier, Clark. "These four indi - viduals have made a positive difference not only in newspapers, but also in their communities and in our state." Way was publisher of the family-owned Watertown Public Opinion from 1942 until 1985. He was instrumental in the development and growth of Watertown. He was a key supporter of the Watertown Com - munity Foundation. Way was inducted into the South Dakota Hall of Fame in 1999. He died in 2006 at the age of 99. Tim Waltner began working at the Freeman Courier in 1973. -

No Extra School Taxes for New K-12 School Building Project Gittings and Peterson Retire Philip Council Notified of Police Chief

$ 00 Inclu1des Tax No. 24, Vol. 110 Philip, South Dakota 57567 Thursday, February 4, 2016 www. pioneer-review.com No extra school taxes for new K-12 school building project by Del Bartels Two financial and architectural experts relayed information and op - tions to the Haakon School District Board of Education during a special meeting, Tuesday, Jan. 26, about a new kindergarten through 12th grade school building to be started the summer of 2017 and ready for classes in fall 2018. The main crux of the discussion was that a new K-12 school building was possible without any raising of current property taxes. The official resolution by the board for the new school building will be voted on during the board’s Monday, Feb. 8 meeting. If that vote and other legalities go according to plan, then community meetings will be held as soon as possible. If anyone opposes the board’s decision, that person has a legal number of days to get signatures on a petition bring - ing the project to a vote by registered voters in the school district. Any election procedure would be held as soon as possible. Bid letting for the construction project should be held soon so construction companies can plan to start the summer of 2017 as soon as warmer weather allows. Plans are for the project to be classroom ready by the fall of 2018. Pay - ment of the project would be over future years, with monies coming out of what the district has in reserves and what is already on the tax books Del Bartels to come in to the school district during those future years. -

March 14Th & 15Th, 2015

PRESS & DAKOTAN n SATURDAY, MARCH 14, 2015 THE MIDWEST: PAGE 9 Lawmakers Work To Finalize SD Budget Sturgis City Park To Host PIERRE (AP) — South Dakota lawmakers are wrapping up the main run of this year’s legislative session and are poised to pass a spending plan Friday for the fiscal year that begins in July. The Joint Appropriations Committee plans to finish Rally Events, Upsetting Some work on the approximately $1.4 billion state budget Friday so the House and Senate can pass the spending measure STURGIS (AP) — City officials plan lease agreement with a promoter to cre- Dave Wilson, a Sturgis resident by the end of the day. to allow vendors and motorcycle shows ate and manage a venue at the park. whose daughter is a soccer player, said Lawmakers on Wednesday adopted revenue estimates in Sturgis City Park during this year’s City officials aren’t releasing details of the city has crossed the line allowing that were lower than projections the governor made for his bike rally, a move that has upset some the contract but say the park activities vendors in the park. December budget. They’re now wrestling with how to bal- business owners and residents. are designed to enhance the experience “Our kids go down there during the ance the budget for Fiscal Year 2016. The decision was made without any of everyone visiting Sturgis during the rally and practice soccer,” he said. “We Legislators will return to the Capitol for a final day at opportunity for residents to comment 75th anniversary rally Aug. -

District Title Name Party Affiliation Home Address City State Zip Phone Legislature Email 1 Sen

District Title Name Party Affiliation Home Address City State Zip Phone Legislature Email 1 Sen. Jason Frerichs Democrat 13507 465th Avenue Wilmot SD 57279 605-938-4273 [email protected] 2 Sen. Brock L. Greenfield Republican 507 N Smith Street Clark SD 57225 605-532-4088 [email protected] 3 Sen. David Novstrup Republican 1008 S Wells Street Aberdeen SD 57401 605-380-9998 [email protected] 4 Sen. Jim Peterson Democrat 16952 482nd Avenue Revillo SD 57259 605-623-4573 [email protected] 5 Sen. Ried Holien Republican PO Box 443 Watertown SD 57201 605-886-4330 [email protected] 6 Sen. Ernie Otten Jr. Republican 46787 273rd St. Tea SD 57064 605-368-5716 [email protected] 7 Sen. Larry Tidemann Republican 251 Indian Hills Road Brookings SD 57006 605-692-1267 [email protected] 8 Sen. Scott Parsley Democrat 103 N Liberty Madison SD 57042 605-256-4984 [email protected] 9 Sen. Deb Peters Republican 705 North Sagehorn Drive Hartford SD 57033 605-321-4168 [email protected] 10 Sen. Jenna Haggar Republican PO Box 763 Sioux Falls SD 57101 605-610-9779 [email protected] 11 Sen. David M. Omdahl Republican PO Box 88235 Sioux Falls SD 57109 605-323-0098 [email protected] 12 Sen. Blake Curd Republican 38 S Riverview Heights Sioux Falls SD 57105 605-331-5890 [email protected] 13 Sen. Phyllis M. Heineman Republican 2005 S Phillips Avenue Sioux Falls SD 57105 605-339-2167 [email protected] 14 Sen. -

Jan 14 Cover Cvr.Qxd

Official Monthly Publication Member of National League of Cities Contents Features www.sdmunicipalleague.org Legal Holidays for 2014 . .4 State Rates . .5 South Dakota 2014 Legislative Calendar . .6 MUNICIPALITIES Carrying Your Message to the Capitol . .7 How an Idea Becomes Law . .8 Managing Editor: Yvonne A. Taylor Editor: Carrie A. Harer How to Track a Bill Online PRESIDENT DISTRICT CHAIRS During the 2014 Session . .9 Becky Brunsing Dist. 1 - Mike Grosek Finance Officer, Wagner Mayor, Webster 2014 Legislators By District . .10-13 1st VICE PRESIDENT Dist. 2 - Tim Reed SDML 2014 Events Calendar . .14 Jeanne Duchscher Mayor, Brookings Finance Officer, Parker Deadwood Grant Funds Available . .15 Dist. 3 - Amy Nelson 2nd VICE PRESIDENT City Manager, Yankton Municipal Elections: Q & A . .16 Meri Jo Anderson 2014 Municipal Election Calendar . .24 Finance Officer, Dist. 4 - Debbie Houseman New Underwood Finance Officer, Lake Andes Ethnic Epithets Supported Pretext Claim TRUSTEES Dist. 5 - Renae Phinney Barring Summary Judgment for Municipality . .26 Laurie Gill President, Ree Heights Mayor, Pierre Enhance Your Leadership by Dist. 6 - Anita Lowary Tapping into Staff Attitudes . .28 Greg Jamison Finance Officer, Groton Councilmember, Sioux Falls Zero-Base Budgeting: Dist. 7 - Arnold Schott A Concept whose Time Has Come – Again . .32 Sam Kooiker, Mayor, McLaughlin Mayor, Rapid City The Quiet Struggle . .38 Dist. 8 - Harry Weller Pauline Sumption Mayor, Kadoka Tense Times Can Test a Manager . .40 Finance Officer, Rapid City Municipal Tax Payments . .50 Dist. 9 - Gary Lipp Mike Wendland Mayor, Custer Mayor, Baltic Columns Dist. 10 - Georgeann Silvernail PAST PRESIDENT Commissioner, Deadwood Director’s Notes . .4 Paul Young Councilmember, Spearfish President’s Report . -

Aurora County 2014 General Election - OFFICIAL RESULTS Precincts Fully Reporting: 714/714 (Precincts Partially Reported: 0)

Aurora County 2014 General Election - OFFICIAL RESULTS Precincts Fully Reporting: 714/714 (Precincts Partially Reported: 0) State Senator - District 20 Precinct Mike Vehle TOTALS Precinct-1 181 181 Precinct-2 97 97 Precinct-3 219 219 Precinct-5 102 102 Precinct-7 191 191 TOTAL 790 790 State Representative - District 20 - 0 (South Dakota) Precinct James V. Schorzmann Tona Rozum Joshua M. KluTOTALS Precinct-1 76 131 159 366 Precinct-2 46 72 100 218 Precinct-3 135 170 165 470 Precinct-5 75 85 78 238 Precinct-7 100 144 146 390 TOTAL 432 602 648 1682 Results provided by the Office of South Dakota Secretary of State Beadle County 2014 General Election - OFFICIAL RESULTS Precincts Fully Reporting: 714/714 (Precincts Partially Reported: 0) State Senator - District 22 Precinct Darrell Raschke Jim White TOTALS Precinct-12 170 454 624 Precinct-15 38 290 328 Precinct-17 62 165 227 Precinct-W1 305 669 974 Precinct-W2 200 285 485 Precinct-W3 153 291 444 Precinct-W7-1 186 426 612 Precinct-W7-2 142 486 628 Precinct-W8-1 155 421 576 Precinct-W8-2 151 401 552 TOTAL 1562 3888 5450 State Representative - District 22 Precinct Peggy Gibson Joan Wollschlager Dick Werner TOTALS Precinct-12 373 192 337 902 Precinct-15 79 44 276 399 Precinct-17 141 86 112 339 Precinct-W1 636 310 512 1458 Precinct-W2 340 197 226 763 Precinct-W3 307 152 207 666 Precinct-W7-1 395 210 354 959 Precinct-W7-2 393 218 373 984 Precinct-W8-1 352 179 345 876 Precinct-W8-2 363 210 300 873 TOTAL 3379 1798 3042 8219 Results provided by the Office of South Dakota Secretary of State Bennett County -

SD Library Association

Members as of December 31, 2013 SD Library Association 2013 Membership Directory Individual Members JANE ABERNATHY Sandra Andera Melanie Argo PO BOX 101 721 2nd Ave NE 1051 N Summit Ave Apt 1 111 2ND ST Aberdeen, SD 57401 209 E Center St PIEDMONT, SD 57769 Roncalli Elementary and Primary Madison, SD 57042 Director Schools Library Assistant Piedmont Valley Library [email protected] Madison Public Library 605‐718‐3663 605‐256‐7525 PATRICIA ANDERSEN [email protected] [email protected] 501 E ST. JOSEPH ST MERRILL ACKERMAN RAPID CITY, SD 57701 Carlene Aro PO Box 71 Director 1018 Circle Drive 1106 B AVE Devereaux Library / SDSM&T HM Briggs Library, SDSU EUREKA, SD 57437‐0071 605‐394‐1255 Brookings, SD 57007 Teacher/Librarian [email protected] Serials Librarian Eureka Public Schools HM Briggs Library, SDSU VICKI ANDERSON 605‐284‐2875 x105 605‐688‐5567 PO Box 26 [email protected] [email protected] 410 Ramsland St. ALISSA ADAMS BUFFALO, SD 57720 JEANNE BAILLIE 12930 E HWY 34 Librarian 702 W HEMLOCK STURGIS, SD 57785 Northwest Regional Library BERESFORD, SD 57004 Library Media Specialist 605‐375‐3835 Trustee Sturgis Brown High School [email protected] Beresford Public Library 605‐347‐2686 605‐763‐5867 H ANDERSON [email protected] [email protected] 1226 E GREENWAY CIRCLE SCOTT AHOLA MESA, AZ 85203 Cheryl Baldyga 125 1/2 W HWY 14 Library Director 610 Quincy St SPEARFISH, SD 57783 Mesa Public Library Rapid City, SD 57701 Director 602‐644‐2336 Rapid City Public Library Black Hills State