GLOBALIZED FEMINISM by Ben Davis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10X10 JAPANESE PHOTOBOOKS September 28-30, 2012 10X10 READING ROOM

10x10 JAPANESE PHOTOBOOKS September 28-30, 2012 Organized by Matthew Carson, Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich 10X10 Reading Room 10x10 Online ICP - Bard MFA Studios photolia.tumblr.com 24-20 Jackson Ave., 3rd Floor, LIC [email protected] icplibrary.wordpress.com 10x10 READING ROOM Atsushi Fujiwara / Asphalt Magazine www.fuji-field.jp/asphalt Eiji Sakurai, Hokkaido 1971 - 1976 (Tokyo: Sokyu sha, 2011) Yoshiichi Hara, Walk while ye have light (Tokyo: Sokyu sha, 2011) Kazuyuki Kawaguchi, Only Yesterday (Tokyo: Sokyu sha, 2010) Takao Niikura, Dizzy Noon (Tokyo: Sokyu sha, 2010) Masakazu Sugiura, Remontage (Tokyo: Sokyu sha, 2009) Shigeichi Nagano, Distant Gaze: Dark Blossom of Winter (Tokyo: Sokyu sha, 2008) Atsuhiro Tsuruta, Black Dock (Tokyo: Sokyu sha, 2008) Yoshiichi Hara, Dark of True (Tokyo: Sokyu sha, 2008) Kanji Mizutani, Indigo (Tokyo: Sokyu sha, 2004) Michio Yamauchi, Stadt (Tokyo: Sokyu sha, 1992) Tomoka Aya / The Third Gallery Aya www.thethirdgalleryaya.com Miyako Ishiuchi , 1・9・4・7 (Tokyo: IPC, 1990) Kiyoshi Suzuki, Soul and Soul: 1969-1999 (Groningen, The Netherlands: Noorderlicht, 2008) Toshiko Okanoue, Drop of Dreams (Tucson, AZ: Nazraeli Press, 2002) Jun Abe, Citizen (Osaka: Vacuum Press, 2009) 10x10 Japanese Photobooks Toshiya Murakoshi, Raining (Tokyo: Sokyu sha, 2006) Shigeo Gocho, Self and Others (Tokyo: Miraisha, 1994) Keiko Nomura, Soul Blue (Tokyo: Silverbooks, Takashi Okimoto, 2012) Seiichi Furuya, Memoires.1984-1987 (Tokyo: Nohara Co. Ltd, 2010) Yoshiko Kamikura, Tamamono (Tokyo: Chikuma-shobo, 2002) Yuko Tada, Strolling in Between: Deer and People on Wakakusayama Hill (Digital book, 2012) Ferdinand Brueggemann / Galerie Priska Pasquer www.priskapasquer.de and japan-photo.info Mika Ninagawa, Liquid Dreams (Tokyo: Editions Treville, 2003) Miyako Ishiuchi, Mother's (Tokyo: Sokyu sha, 2002) Rinko Kawauchi. -

Books Keeping for Auction

Books Keeping for Auction - Sorted by Artist Box # Item within Box Title Artist/Author Quantity Location Notes 1478 D The Nude Ideal and Reality Photography 1 3410-F wrapped 1012 P ? ? 1 3410-E Postcard sized item with photo on both sides 1282 K ? Asian - Pictures of Bruce Lee ? 1 3410-A unsealed 1198 H Iran a Winter Journey ? 3 3410-C3 2 sealed and 1 wrapped Sealed collection of photographs in a sealed - unable to 1197 B MORE ? 2 3410-C3 determine artist or content 1197 C Untitled (Cover has dirty snowman) ? 38 3410-C3 no title or artist present - unsealed 1220 B Orchard Volume One / Crime Victims Chronicle ??? 1 3410-L wrapped and signed 1510 E Paris ??? 1 3410-F Boxed and wrapped - Asian language 1210 E Sputnick ??? 2 3410-B3 One Russian and One Asian - both are wrapped 1213 M Sputnick ??? 1 3410-L wrapped 1213 P The Banquet ??? 2 3410-L wrapped - in Asian language 1194 E ??? - Asian ??? - Asian 1 3410-C4 boxed wrapped and signed 1180 H Landscapes #1 Autumn 1997 298 Scapes Inc 1 3410-D3 wrapped 1271 I 29,000 Brains A J Wright 1 3410-A format is folded paper with staples - signed - wrapped 1175 A Some Photos Aaron Ruell 14 3410-D1 wrapped with blue dot 1350 A Some Photos Aaron Ruell 5 3410-A wrapped and signed 1386 A Ten Years Too Late Aaron Ruell 13 3410-L Ziploc 2 soft cover - one sealed and one wrapped, rest are 1210 B A Village Destroyed - May 14 1999 Abrahams Peress Stover 8 3410-B3 hardcovered and sealed 1055 N A Village Destroyed May 14, 1999 Abrahams Peress Stover 1 3410-G Sealed 1149 C So Blue So Blue - Edges of the Mediterranean -

"The Wings of Miwa Yanagi," the Translation of Special Issue On

special issue Feature Interview The Wings of Miwa Yanagi Miwa Yanagi has wings, and she flies easily across the borders of different art genres. She majored in textile dyeing in her school years, but shifted to contemporary art, creating photography and video work using computer graphics. Since 2012, she has been also been a professor at the Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Kyoto University of Art and Design. The next place she landed at was theater. In the past four years, she has been organizing many plays based on modern Japan, as if excavating hidden voices of people buried in history. In 2014, she introduced the Taiwanese moving stage (stage trailer) to Japan for the first time. Together with students of Kyoto University of Art and Design, Tohoku University of Art & Design, and Taipei National University of the Arts, the moving stage they made in Taiwan will be “drifting” to various places after “landing ashore” at Yokohama Triennale. A pilgrimage and tour begins with “Wings of the Sun,” a road novel by the late novelist, Kenji Nakagami. Photography:Shen Chao-Liang What does this touring performance mean to her? The stage trailer unfolds and the stage appears. In Taiwan. As Miwa Yanagi is on a quest to find her ideal expression, we too chase after her as she continues to fly on the artistic stage. 1 2 make things using my hands. Being in the classical and traditional Departments of Crafts, I didn't know much about art when I was an undergraduate student. Of course, I was familiar with Dumb Type1 or Yayoi Kusama2, but I didn't quite understand the concept of contemporary art even if I visited an exhibition. -

Japan Society's Press Release on "Zero Hour"

Press Contacts: Performing Arts/General: Bridget Klapinski, 347-246-6182 [email protected] *Music Events: John Seroff, 201-743-8536 [email protected] Shannon Jowett, Japan Society, 212-715-1205 [email protected] Japan Society Presents Miwa Yanagi’s Zero Hour: Tokyo Rose’s Last Tape Part of Japan Society’s 2014-2015 Performing Arts Season, this Production Launches Society-wide Series: Stories from the War Marking the 70th Anniversary of the End of WW II Three Performances Only: January 29, 30, 31 at 7:30pm Japan Society (333 East 47th Street) New York, NY, January 12, 2015 – As part of its 2014-2015 Performing Arts Season, Japan Society proudly presents Zero Hour: Tokyo Rose’s Last Tape, the first theater production within the Society-wide series Stories from the War, marking the 70th Anniversary of the end of WWII. This multimedia work conceived, written and directed by internationally renowned visual artist Miwa Yanagi marks a North American premiere, playing 3 performances: Thursday, January 29 – Saturday, January 31 at 7:30pm. Following this premiere at Japan Society, Zero Hour: Tokyo Rose’s Last Tape will have performances at The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington, DC (2/6 & 2/7); Asian Arts & Culture Center at Towson University, Towson, MD (2/13); Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre, Toronto, Canada (2/21) and REDCAT (Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater), Los Angeles, CA (2/26-2/28) as part of a North American tour produced and organized by Japan Society. 1943. In the midst of WWII, the voice of a female announcer on ‘Radio Tokyo,’ Japan’s state-run international radio service, reached the ears of U.S. -

Popular Culture and Gender Issues in Miwa Yanagi's Art Practice A

KRESTINA SKIRL Popular Culture and Gender Issues in Miwa Yanagi's Art Practice A Critical Approach Towards Images of Identity and Femininity Currently Circulating in Japanese Popular Culture This paper explores the crossover between art and popular culture in the art practice of the contemporary Japanese artist Miwa Yanagi, arguing that her art works seem to take a critical approach towards images of identity - and above all images of femininity - currently circulating in Japanese popular culture. At the same time, this paper also demonstrates that Miwa Yanagi’s works appear to engage in issues of identity and gender from a more overall and philosophical perspective, in a way which moves beyond an entirely Japanese context. Note: all illustrations included by courtesy of the artist. By Krestina Skirl and working in Kyoto where she completed a Master’s This paper concerns the art practice of the degree in Art Research at Kyoto City University of Arts contemporary Japanese artist Miwa Yanagi (b. 1967) and held her first solo exhibition in 1993, Miwa Yanagi which can be said to be of current interest. Not only has been experimenting with photography, video and because Miwa Yanagi was appointed as artist for the computer graphics for years to create art works which Japanese Pavilion at the 53rd Venice Biennale of Art are centred on the subject of women. Her works present held in 2009. But also because her art practice forms various images of femininity and different types of part of a newer tendency in Japanese contemporary art women, but in a way which challenges existing gender which refers to or interacts with social and economical roles. -

Photographic Expression in Japan (2009)

Photographic Expression in Japan (2009) Kotaro Iizawa(Photographic Critic) Due to the impact of the simultaneous slowdown of the world economy in the autumn of 2008, 2009 was an exceptionally difficult year economically. Fields with deep ties to photography, such as advertising and publishing, were struck particularly hard, and I frequently hear stories, too, of how the livelihood of photographers is becoming threatened. However, the harsh economic situation and society’s siege mentality cannot entirely be said to have been reflected directly in the sphere of photographic expression. Instead, it could be said that it is precisely in gloomy situations such as this that the fundamental strength of photography is freshly questioned. Looking at the situation regarding the publication of photographic collections or staging of photographic exhibitions in 2009, activity was in fact more vigorous than in the past, and of this we believe there were also much of high quality. The huge wave of “digitalization” that has exerted a clear effect since we entered the 2000s has also settled down, and works exhibiting firm mastery of the new media and technology are beginning to stand out. Major Photographic Awards The 34th Ihei Kimura Award was presented to Masashi Asada for his photographic collection “Asadake (The Asada Family)” (Akaakasha), which comprises two photographic series: “dress-up photographs” of the photographer, his parents, and elder brother in the costumes of various occupations, from fire fighters to rock’n rollers; and commemorative photographic poses from the Asada family album. The collection is an experiment in new “family photos” that physically and critically questions the image of the modern family within which lies a sense of danger. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE JAPAN PAVILION at the 53rd International Art Exhibition - La Biennale di Venezia Miwa Yanagi Windswept Women: The Old Girls' Troupe Commissioner: Hiroshi Minamishima Miwa Yanagi represents Japan at the 53rd Venice Biennale with her installation entitled Windswept Women: The Old Girls’ Troupe. For this installation, Yanagi will take the Takamasa Yoshizaka-designed Japan Pavilion built in 1956 and cover its exterior with a black, membrane-like tent. Invoking the original idea of a “pavilion” as a free standing or temporary structure, the fluidity and mobility of the tent form will turn the Japan Pavilion into a temporary playhouse. Inside, Yanagi will install giant 4m high photograph stands containing portraits of women of varied ages. A new video work and series of small photographs will also be shown. Upon entering, viewers will feel disoriented, losing their sense of scale and perspective as they walk among oversized works. The motif of this installation is a troupe comprised exclusively of women traveling with their mobile house—a tent—on the top of their caravan. This tent, inspired by the novels of Japanese modernist writer Kobo Abe, has already appeared in Yanagi’s previous Fairy Tales (2004-05) series of staged photographs, and has been a key to expressing ambivalent themes such as the tensions between “life and death,” “past and future,” “confinement and mobility” and “everyday life and festival.” The photographs of gigantic women Yanagi has created for Venice symbolize resolution. They stand unmoved despite being surrounded by turbulent wind. No matter happens, they will keep their feet planted firmly on the ground. -

Postwar Japanese Photography: a Selected Bibliography Thomas F

Postwar Japanese Photography: A Selected Bibliography Thomas F. O’Leary, Anat Icar-Shoham, Patricia Lenz, Shir Yeffet Review of Japanese Culture and Society, Volume 31, 2019, pp. 242-271 (Article) Published by University of Hawai'i Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/roj.2019.0019 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/782279 [ Access provided for user 'hawaiijrnls' at 23 Mar 2021 02:10 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] Author Kawada Kikuji, The Last Sunrise of Showa Era, 1989 January 7, from the series The Last Cosmology. ©︎ Kikuji Kawada. Courtesy PGI, Michael Hoppen Gallery. 242 REVIEW OF JAPANESE CULTURE AND SOCIETY 2019 Author Postwar Japanese Photography: A Selected Bibliography Edited by Thomas F. O’Leary and compiled by Anat Icar-Shoham, Patricia Lenz, and Shir Yeffet Overview and Introduction The first daguerreotypes and cameras arrived in Japan in 1848, less than a decade after the invention of photography in the West. From that moment on, photography has remained a central aspect of Japanese visual culture, ranging from the portrait studios of Yokohama to the contemporary photographers of today. The history of photography in Japan is as intertwined with its visual and popular culture, as it is in Europe and the United States. The study of Japanese photography in Europe and the United States has been growing steadily since the end of World War Two and, in particular, since 1974 when the Museum of Modern Art in New York held its New Japanese Photography exhibition curated by John Szarkowski and Yamagishi Shōji. This exhibition featured photographers such as Domon Ken, Hosoe Eikoh, Tōmatsu Shōmei, and Moriyama Daidō, names that will be familiar to anyone with an interest in the history of Japanese photography. -

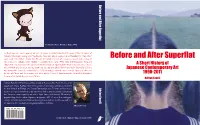

Before and After Superflat Before And

Before and After Superflat Yoshitomo Nara, Harmless Kitty (1994) Contemporary Art 1990 - 2011 Contemporary Art 1990 A Short History of Japanese Talk of Japanese contemporary art and everyone inevitably thinks of the pop culture fantasies of Takashi Murakami, along with Yoshitomo Nara and others connected to Murakami’s “Superflat” movement. Meanwhile, Japan has stumbled through a series of economic, social and ecological Before and After Superflat crises since the collapse of its “Bubble” economy in the early 1990s. How did Murakami, Nara and “Superflat” rise to become the dominant artistic vision of Japan today? What lies behind their image A Short History of of a childish and decadent society unable to face up to reality? Before and After Superflat tellstells thethe Japanese Contemporary Art truetrue storystory ofof thethe JapaneseJapanese artart worldworld sincesince 1990,1990, itsits strugglestruggle toto findfind aa voicevoice amidstamidst Japan’sJapan’s declinedecline andand thethe riserise ofof China,China, andand thethe responsesresponses ofof otherother artists,artists, lessless wellwell knownknown outside,outside, whowho offeroffer alternativealternative 1990-2011 visions of its troubled present and future. Adrian Favell Adrian Favell is a Professor of Sociology at Sciences Po, Paris. He has also taught at UCLA, Aarhus University and the University of Sussex. In 2007 he was invited to Tokyo as a Japan Foundation Abe Fellow, and has since Favell Adrian then been closely involved as an observer, writer and occasional curator on the Japanese contemporary art scene, both home and abroad. He writes a popular blog for the online Japanese magazine ART-iT, as well as catalogue essays, reviews and contributions to magazines such as Art Forum and Art in America. -

Miwa Yanagi: Biography

Miwa Yanagi: Biography Born in Kobe City. Completed the postgraduate course of Kyoto City University of Arts Lives and works in Kyoto <Solo Exhibitions> 1993 “The White Casket” Art Space Niji, Kyoto 1994 “Looking for the next story” Gallery Sowaka, Kyoto 1997 “Criterium 31” Contemporary Art Center/Gallery, Art Tower Mito, Ibaraki 2000 “Miwa Yanagi” Galerie Almine Rech, Paris, France 2002 “My Grandmothers” Galerie Almine Rech, Paris, France “Miwa Yanagi” Istituto Giapponese di Cultura in Roma, Rome, Italy “Granddaughters” Shiseido Gallery, Tokyo “Miwa Yanagi” Fukuoka Art Museum, Fukuoka “My Grandmothers” Kirin Plaza Osaka, Osaka 2003 “My Grandmothers” Wohnmaschine, Berlin, Germany “Miwa Yanagi” Galería Leyendecker, Canary Islands, Spain 2004 “Miwa Yanagi-Sammlung Deutsche Bank” Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin, Germany “Granddaughters” Lille 2004, Lille, France “Darkness of Girlhood & Lightness of Aging” Marugame Genichiro-Inokuma Museum of Contemporary Art, Kagawa “Fairy Tale” Galería Leyendecker, Canary Islands, Spain 2005 “The Incredible Tale of the Innocent Old Lady and the Heartless Young Girl” Hara Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo “Madame Comet” Yurinso,Ohara museum of Art, Okayama 2007 “Miwa Yanagi” Chelsea Art Museum, New York <Group Exhibitions> 1994 “ART NOW ’94” Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, Hyogo 1995 “Contemporary Art from Galleries ’95” Osaka Contemporary Art Center, Osaka 1996 “Prospect ’96” Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany “Art in Flux IV: Oh, My ‘Japanese Landscapes’?” Fukuoka Art Museum, Fukuoka 1997 -

Masaki Fujihata Born 1956 in Tokyo/JPN Lives in Tokyo/JPN

Masaki Fujihata Rieko Hidaka Takashi Ito Index born 1956 in Tokyo/JPN born 1958 in Tokyo/JPN born 1956 in Fukuoka/JPN lives in Tokyo/JPN lives in Tokyo/JPN lives in Kyoto/JPN Exhibitions (selection) Exhibitions (selection): Films and Festivals (selection): Field-Work@Alsace, Lisboa Rieko Hidaka – Trees, Northland Monochrome Head, 10:00 min, 16- Photo2005, Lisbon 2005; Field- Museum of Art, Hokkaido 2004; mm, 1997; Apparatus M, 6:00 min, Work@Alsace, Microwave Festival, Rieko Hidaka, Galerie 16, Kyoto 2004; 16-mm, 1997 (shown in the exhibi- Low Block, Hong Kong City Hall, Rieko Hidaka, Art Kite Museum, tion Yasumasa Morimura – The Hong Kong 2004; Mersea Circle, Detmold 2003; Masterpieces in CAMK Sickness unto Beauty, Yokohama firstsite gallery, Colchester 2003; selection – Today’s Japanese Tradi- Museum of Art, Yokuhama 1996); Beyond Pages – Im Buchstabenfeld. tional Painting, Contemporary Art Zone, 13:00 min, 16-mm, 1995; New Die Zukunft der Literatur, Neue Museum, Kumamoto 2003; Komorebi, York Film Festival 1995; Oberhausen Galerie Graz am Landesmuseum Contemporary Art Gallery, Art International Film Festival 1996; Joanneum/steirischer herbst, Graz Tower Mito, Ibaraki 2003; Painting Brisbane International Film Festival 2001; Field-Work@Hayama, Ars in our time, The Niigata Bandaijima 1996; Vancouver International Film Electronica Festival, Linz 2001; Art Museum, Niigata 2003; Rieko Festival 1996; Tampere International Impressing Velocity, net conditions, Hidaka – From the Space of Trees, Short Film Festival 1996; ZKM, Karlsruhe 1999; Global Interior Tomio Koyama Gallery, Tokyo 2002, New Zealand Film Festival 1996; Project, Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle Galerie 16, Kyoto 2002; Here is the The Moon, 7:00 min, 16-mm, 1994; der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Museum, the scape collaborated with Rotterdam International Film Festival Bonn 1997; Global Interior Project our collection, artists and you – The 1995; Vancouver International Film and Beyond Pages, Ars Electronica Encounter of our Collection and 4 Festival 1995; Kerala International Festival, Linz 1996. -

Miwa Yanagi: Biography

Miwa Yanagi: Biography Born in Kobe City. Completed the postgraduate course of Kyoto City University of Arts Lives and works in Kyoto <Solo Exhibitions> 1993 “The White Casket” Art Space Niji, Kyoto 1994 “Looking for the next story” Gallery Sowaka, Kyoto 1997 “Criterium 31” Contemporary Art Center/Gallery, Art Tower Mito, Ibaraki 2000 “Miwa Yanagi” Galerie Almine Rech, Paris, France 2002 “My Grandmothers” Galerie Almine Rech, Paris, France “Miwa Yanagi” Istituto Giapponese di Cultura in Roma, Rome, Italy “Granddaughters” Shiseido Gallery, Tokyo “Miwa Yanagi” Fukuoka Art Museum, Fukuoka “My Grandmothers” Kirin Plaza Osaka, Osaka 2003 “My Grandmothers” Wohnmaschine, Berlin, Germany “Miwa Yanagi” Galería Leyendecker, Canary Islands, Spain 2004 “Miwa Yanagi-Sammlung Deutsche Bank” Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin, Germany “Granddaughters” Lille 2004, Lille, France “Darkness of Girlhood & Lightness of Aging” Marugame Genichiro-Inokuma Museum of Contemporary Art, Kagawa “Fairy Tale” Galería Leyendecker, Canary Islands, Spain 2005 “The Incredible Tale of the Innocent Old Lady and the Heartless Young Girl” Hara Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo “Madame Comet” Yurinso,Ohara museum of Art, Okayama “Fairy Tale” Wohnmaschine, Berlin 2007 “Miwa Yanagi” Chelsea Art Museum, New York “Miwa Yanagi -Recent works” Byblos Art Gallery, Verona, Italy 2008 “Miwa Yanagi” The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas 2009 “My Grandmothers” Tokyo Metropolitan Museum f Photography, Tokyo “Windswept Women-The Old Girls’ Troupe” 53rd Venezia Biennale, Japan pavilion, Italy “Po-Po