Re-Visiting Angela Carter Books by the Same Author (Ed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marxist Feminism and Postmodern Elements in Angela Carter's Nights

INFOKARA RESEARCH ISSN NO: 1021-9056 Marxist Feminism and Postmodern Elements in Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus R.Padhmavathi Ph.D Researchscholar Department of English Email id:[email protected] AnnamalaiUniversity ,Chidhambaram. Dr.A.Glory , Asst.professor, Department of English Annamalai University, Chidhambaram Abstract: This paper endeavors to examine critically and analytically how the Marxist feminism is developed in Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus (1984), and how the postmodernistic ideas in her mind. It sheds light on the feminine themes and concerns, and in this novel Angela Carter speaks out lots of feminine matters and moves around strongly in her mind. Her lasting fascination with femininity as vision has until then been understood mainly in terms of a feminist critical project which identifies and rejects male-constructed images of women as a form of false consciousness. Keywords: Feminism, Marxism, Carnivalisation, Postmodernism Marxist Feminism and Postmodern Elements in Angela Carter’s Nights At The Circus Angela Carter’s achievements asa feminist are clearly understood only if we look at her novels with postmodern eyes. Her novels make no sense unless they are given a postmodern reading which can extricate the challenging thoughts on the essence of womanhood that lie entangled in fantasies, dreams, myths, and parodies. Through reading the novels of Angela Carter, it is noticeable that she goes in the femininity track in her fictional writings. HerNights at the Circus is a novel about the ways in which these dominant, frequently male-centered discourses of power marginalize those whom society defines as freaks, madmen, clowns, the physically and mentally deformed, and, in particular, women, so that they may be contained and controlled because they are all possible sources of the disordered disruption of established power. -

The Quest for Female Empowerment in Angela Carter's Wise Children

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy “I AM NOT SURE IF THIS IS A HAPPY ENDING” THE QUEST FOR FEMALE EMPOWERMENT IN ANGELA CARTER’S WISE CHILDREN Supervisor: Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of Professor Marysa Demoor the requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels” by Aline Lapeire 2009-2010 Lapeire ii Lapeire iii “I AM NOT SURE IF THIS IS A HAPPY ENDING” THE QUEST FOR FEMALE EMPOWERMENT IN ANGELA CARTER’S WISE CHILDREN The cover of Wise Children (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007) Lapeire iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation could not have been written without the help of the following people. I would hereby like to thank… … Professor MARYSA DEMOOR for supporting my choice of topic and sharing her knowledge about gender studies. Her guidance and encouragement have been very important to me. … DEBORA VAN DURME and Professor SINEAD MCDERMOTT for their interesting class discussions of Nights at the Circus and Wise Children. Without their keen eye for good fiction, I might have never even heard of Angela Carter and her beautiful oeuvre. … Several very patient librarians at the University of Ghent. … A great deal of friends who at times mocked the idea of a „gender dissertation‟, yet always showed their support when it was due. I especially want to thank my loyal thesis buddies MAX DEDULLE and MARTIJN DENTANT. The countless hours we spent together while hopelessly staring at a world behind the computer screen eventually did pay off. Moreover, eternal gratitude and a vodka-Red Bull go out to JEROEN MEULEMAN who entirely voluntarily offered to read and correct my thesis. -

The Transgender Subject, Experimental Narrative and Trans-Reading Identity in the Fiction of Virginia Woolf, Angela Carter, and Jeanette Winterson

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 7-2006 “A Highly Ambiguous Condition”: The Transgender Subject, Experimental Narrative and Trans-Reading Identity in the Fiction of Virginia Woolf, Angela Carter, and Jeanette Winterson Jennifer A. Smith Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Jennifer A., "“A Highly Ambiguous Condition”: The Transgender Subject, Experimental Narrative and Trans-Reading Identity in the Fiction of Virginia Woolf, Angela Carter, and Jeanette Winterson" (2006). Dissertations. 990. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/990 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “A HIGHLY AMBIGUOUS CONDITION”: THE TRANSGENDER SUBJECT, EXPERIMENTAL NARRATIVE AND TRANS-READING IDENTITY IN THE FICTION OF VIRGINIA WOOLF, ANGELA CARTER, AND JEANETTE WINTERSON by Jennifer A. Smith A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Dr. Gwen Raaburg, Advisor Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan July 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. “A HIGHLY AMBIGUOUS CONDITION”: THE TRANSGENDER SUBJECT, EXPERIMENTAL NARRATIVE AND TRANS-READING IDENTITY IN THE FICTION OF VIRGINIA WOOLF, ANGELA CARTER, AND JEANETTE WINTERSON Jennifer A. Smith, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2006 This dissertation examines how the constantly evolving gender identity of a text’s transgender subject relates to the text’s narrative structure and shapes the orientation of the reader to the text. -

Feminist Subversion of Fairy-Tale Female Characters in Angela Carter's

100 ORIGINALNI NAUĈNI RAD DOI: 10.5937/reci1912100G UDC: 821.111.09-31 Karter A. 821.111.09:305-055.2"19" AnĊelka M. Gemović* University of Novi Sad Faculty of Philosophy FROM CAPTIVITY TO BESTIALITY: FEMINIST SUBVERSION OF FAIRY-TALE FEMALE CHARACTERS IN ANGELA CARTER’S “THE TIGER’S BRIDE” Abstract: This paper elaborates on Angela Carter‟s subversion of the fairy-tale genre in the tale from The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories titled “The Tiger‟s Bride”. The method of research combines researching relevant theoretical literature and thorough text analysis. The primary concern of this paper is the subversion of female characters in fairy tales as a means of advocating feminist attitudes. Relevant passages are used to exemplify Carter‟s feminism, with special reference to the subverted roles of the heroine of the tale. The female protagonist‟s transition from being a captive to becoming a beast is analysed, and her reinvented roles discussed and compared to the traits of the heroine from the classic Beauty and the Beast story written by De Beaumont. This is done in order to uncover the multilayered structure of Carter‟s work and hopefully determine the author‟s genuine purpose in subverting the fairy-tale genre as well as the message she wanted to convey. Key words: beast tales, The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories, Carter‟s feminism, Beauty and the Beast, women empowerment. * [email protected] 2 0 1 9 FROM CAPTIVITY TO BESTIALITY: FEMINIST SUBVERSION OF FAIRY- TALE FEMALE CHARACTERS IN ANGELA CARTER’S “THE TIGER’S BRIDE” 101 INTRODUCTION Angela Carter was an English novelist, short story writer, poet, journalist, professor and critic known for her feminist and nonconformist attitudes that she deliberately conveyed throughout her work. -

The Consumption of Angela Carter

The Consumption of Angela Carter: Women, Toody and Power EMMA PARKER A great writer and a great critic, V. S. Pritchett, used to sav that he swallowed Dickens whole, at the risk of indigestion. I swallow Angela Carter whole, and then I rush to buy Alka Seltzer. The "minimalist" nouvelle cuisine alone cannot satisfy my appetite for fiction. I need a "maximalist" writer who tries to tell us many things, with grandiose happenings to amuse me, extreme emotions to stir my feelings, glorious obscenities to scandalise me, brilliant and malicious expressions to astonish me. (Almansi 217) L Vs GUIDO ALMANSI suggests, consuming Angela Carter's fic• tion is simultaneously satisfying and unsettling. This is partly because, as Hermione Lee has commented, Carter "was always in revolt against the 'tyranny of good taste'" (316). As a cham• pion of moral pornography, a cultural dissident who dared to disparage Shakespeare, and a culinary iconoclast who criticised the highly-esteemed cookery writer Elizabeth David, Carter out• raged many people. Yet this impiety also gives her work its ap• peal.1 Like the critical essays, her fiction is deliciously "improper" in that it interrogates and rejects what Hélène Cixous calls the realm of the proper, a masculine economy based on the principles of authority, domination and owner• ship — a realm in which, disempowered and dispossessed, women are without property ("Castration" 42, 50). Her fiction has an unsettling effect precisely because Carter seeks to "up• set" the patriarchal order, in part through her representation of consumption, which, by revealing and refiguring the relation• ship between women, food, and power, challenges the struc• tures that underpin patriarchy. -

Identity I N Angela Carter's Nights at the Circus and Wise Children

Performing (and) Identity In Angela Carter's Nights at the Circus and Wise Children Janine Root @ B .A. B. Ed A cnesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English, Lakehead University, Thnder Bay, Ontario, 1999 National Library BibliotMy nationale 1*1 ofCanada du Cana a Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wauinglm Strwt 385. rue WdlingWn WONK1AW o(I.waON K1AW Cwudr CMed. The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence dowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Libmy of Cana& to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduke, prster, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fonnat electronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent &e imprimes reproduced without the author' s ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. Abstract In her last two novels, Nights at the Circus and Wise Children, Angela Carter examines some of the complex factors involved in the construction of identity, both within the fictional world, and for readers in their interaction with 'Le .jn-74 ,., I ,,,, 2f the fictix. 35 zhese f3ctxs, qezier is cf primary importance. -

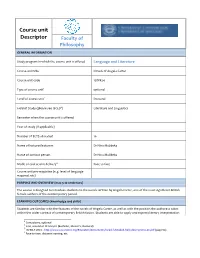

Course Unit Descriptor

Course unit Descriptor Faculty of Philosophy GENERAL INFORMATION Study program in which the course unit is offered Language and Literature Course unit title Novels of Angela Carter Course unit code 15DFk24 Type of course unit1 optional Level of course unit2 Doctoral Field of Study (please see ISCED3) Literature and Linguistics Semester when the course unit is offered Year of study (if applicable) Number of ECTS allocated 10 Name of lecturer/lecturers Dr Nina Muždeka Name of contact person Dr Nina Muždeka Mode of course unit delivery4 Face to face Course unit pre-requisites (e.g. level of language required, etc) PURPOSE AND OVERVIEW (max 5-10 sentences) The course is designed to introduce students to the novels written by Angela Carter, one of the most significant British female authors of the contemporary period. LEARNING OUTCOMES (knowledge and skills) Students are familiar with the features of the novels of Angela Carter, as well as with the position the authoress takes within the wider context of contemporary British fiction. Students are able to apply and express literary interpretation 1 Compulsory, optional 2 First, second or third cycle (Bachelor, Master's, Doctoral) 3 ISCED-F 2013 - http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Documents/isced-f-detailed-field-descriptions-en.pdf (page 54) 4 Face-to-face, distance learning, etc. effectively. SYLLABUS (outline and summary of topics) Lectures Angela Carter, contemporary British novel, feminist theory and engaged writing. Shadow Dance as parodic contemporary gothic fiction. Let’s begin countering patriarchal stereotypes: The Magic Toyshop. Several Perceptions: generation gap and the counterculture of the 60s. -

Angela Carter's Nights at the Circus: a Feminist Spatial Journey to Emancipation and Gender Justice

International Review of Literary Studies IRLS 2 (2) December 2020 ISSN: Online 2709-7021; Print 2709-7013 Angela Carter’s Nights at The Circus: A Feminist Spatial Journey to Emancipation and Gender Justice Dr. Wiem Krifa1 International Review of Literary Studies Vol. 2, No. 2; December 2020, pp. 46- 61 Published by: MARS Research Forum Received: October 10, 2020 Accepted: December 15, 2020 Published: December 22, 2020 Abstract Mobility can be considered as a natural characteristic of human beings, regardless of gender, sex or geographical roots. Within the feminist postmodern context, mobility ushers women in a new world based on gender equality and tolerance. Angela Carter’s Nights at The Circus displays a female character who achieves her New Woman status while traveling from one country to another, as a circus aerialist. Fevvers’ train journey from London to Siberia, together with her lover, empowers her female being. Space proves to be a substantial prerequisite for the achievement of the human subjectivity whether the female or the masculine one. Carter’s heroine succeeds to overcome the patriarchal misogynist attitude that surrounds her professional career and ends by achieving her female subjectivity. Besides, she triumphs to metamorphose Walser from the traditional male figure who looks to debunk Fevvers ‘claimed bird origin, into the new postmodern man who believes in gender equality and surrenders to Fevvers’love. All along their journey, Fevvers, Walser and other female characters, undergo a deep transformation at the level of their personal growth and subjectivities. They overcome their culturally internalized believes, to be prepared for a life based on equal principles and free from the imposed patriarchal cultural constraints. -

Feminism and Sexuality in Angela Carter's Shadow Dance And

International Journal of Research p-ISSN: 2348-6848 e-ISSN: 2348-795X Available at https://edupediapublications.org/journals Volume 04 Issue 01 January2017 Contextualizing Bluebeard Patriarchy through Grotesque: Feminism and Sexuality in Angela Carter’s Shadow Dance and Heroes and Villains Ms. Richa Arora Ph.D Scholar, Lovely Professional University Phagwara SUPERVISED BY Dr J.P. Aggarwal ABSTRACT The purpose of this research paper is to bring awareness to the students of post-colonial fiction of Angela Carter. She won Nobel Prize for literature for her revolutionary feminism and deconstruction of patriarchy. Carter gives the image of the wolf to characterize the monstrous quality of his Bluebeards in her novels. The wolf is a deadly; in each plot of her novels there is a deadly conflict between wolf and the dove. Carter uses all the elements of the Gothic novels of Mrs. Anne Redcliff to create an atmosphere of horror and supernaturalism. The forces of darkness are in tune with the threatening atmosphere of the novel symbolizing death and destruction. Carter has used this tool in her short stories The Bloody Chamber as well. Carter uses the images of mirror, snow, blood, moon, fire, forest and old castles to depict the presence of her Bluebeards symbolic of bloodthirsty traditional patriarchy. In this study the main issues of sexuality of women, gender discrimination are investigated in detail. KEY WORDS: Traumatic, Holocaust, Community, Barbaric, Trilogy, Strategy The themes of power, gender, and „female Gothic‟” (Munford 61). Gamble sexuality dominate the novels of Angela Carter; contends that “Her heroines cover the whole she belongs to the Second Wave of feminism and range from objectified victims to oppressors of wanted to launch a crusade against male others” (Gamble 68). -

Angela Carter's (De)Philosophising of Western Thought

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Angela Carter's (de)philosophising of Western thought. Yeandle, Heidi How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Yeandle, Heidi (2014) Angela Carter's (de)philosophising of Western thought.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42410 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Angela Carter’s (de)philosophising of Western Thought Heidi Yeandle Submitted to Swansea University in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Swansea University 2014 ProQuest Number: 10798118 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Illinois Association for Gifted Children Journal, 2003. INSTITUTION Illinois Association for Gifted Children, Palatine

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 477 217 EC 309 630 AUTHOR Smutny, Joan Franklin, Ed. TITLE Illinois Association for Gifted Children Journal, 2003. INSTITUTION Illinois Association for Gifted Children, Palatine. PUB DATE 2003-00-00 NOTE 66p.; Published annually. For the 2002 issue, see EC 309 629. AVAILABLE FROM Illinois Association for Gifted Children, 800 E. Northeast Highway, Suite 610, Palatine, IL 60067-6512 (nonmembers, $25). Tel: 847-963-1892; Fax: 847-963-1893. PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Illinois Association for Gifted Children Journal; 2003 EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Ability Identification; Cognitive Style; *Creativity; *Curriculum Design; *Curriculum Enrichment; Educational Strategies; Elementary Secondary Education; *Gifted; Music Activities; Poetry; Underachievement ABSTRACT This issue of the Illinois Association for Gifted Children (IAGC) Journal focuses on curriculum. Featured articles include: (1) "Curriculum: What Is It? How Do You Know if It Is Quality?" (Sally Walker); (2) "Tiered Lessons: What Are Their Benefits and Applications?" (Carol Ann Tomlinson); (3) "Do Gifted and Talented Youth Get Counseling, Models, and Mentors To Motivate Them To Strive for Expertise and Creative Achievement?" (John F. Feldhusen);(4) "Biography Is the People Subject" (Jerry Flack); (5) "Abraham Lincoln: Gifted Man and a Hero for the Ages" (Jerry Flack);(6) "Responding to Failure" (Ann MacDonald and Jim Riley); (7) "The Not-So Gifted Parent: Replacing Trial and Error with Identification and Intervention" (Monica Lu); (8) "They Don't Teach THAT in School" (Dorothy Funk-Werbio): (9) "A Poet in a Classroom of Engineers and Lawyers: Identifying and Meeting the Needs of Artistically Gifted Children" (Nancy Elf and Pat Rose); (10) "A Visit from a Poet and Other Literary Devices" (J. -

Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives

Postmodern Openings ISSN: 2068 – 0236 (print), ISSN: 2069 – 9387 (electronic) Coverd in: Index Copernicus, Ideas. RePeC, EconPapers, Socionet, Ulrich Pro Quest, Cabbel, SSRN, Appreciative Inquery Commons, Journalseek, Scipio EBSCO Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives Ileana BOTESCU – SIRETEANU Postmodern Openings, 2010, Year 1, VOL.3, September, pp: 93-138 The online version of this article can be found at: http://postmodernopenings.com Published by: Lumen Publishing House On behalf of: Lumen Research Center in Social and Humanistic Sciences BOTESCU–SIRETEANU, I.,(2010) Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives, Postmodern Openings, Year 1, Vol 3, September, 2010, pp: 93-138 Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives Ileana BOTESCU – SIRETEANU8 Abstract In a world where meaning has been deconstructed and reconstructed, where centers have lost their hegemony and notions such as truth, knowledge or history have been rendered relative by the ongoing ontological enquiry of the postmodern ideology, it is baffling to remark that not only in literature, but also in other fields that make use of discourses, there has been a return to and a reconsideration of the narrative. Nowadays, one can easily observe the narrative drive that enlivens various discourses, from the medical one to the one used in the academe or in official governmental documents. Brian McHale has even referred to the „narrative turn” in literary theory which, according to him, seems to answer to the loss of the metaphysical (McHale 4). Keywords: narrative turn, feminism, narrative dynamics, 8 Ileana BOTESCU – SIRETEANU – “Transilvania” University from Brasov, Romania, Email Address: [email protected].