Comparing the Practices of US Golf Against a Global Model for Integrated Development of Mass and High Performance Sport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sideways Title Page

SIDEWAYS by Alexander Payne & Jim Taylor (Based on the novel by Rex Pickett) May 29, 2003 UNDER THE STUDIO LOGO: KNOCKING at a door and distant dog BARKING. NOW UNDER BLACK, A CARD -- SATURDAY The rapping, at first tentative and polite, grows insistent. Then we hear someone getting out of bed. MILES (O.S.) ...the fuck... A door is opened, and the black gives way to blinding white light, the way one experiences the first glimpse of day amid, say, a hangover. A worker, RAUL, is there. MILES (O.S.) Yeah? RAUL Hi, Miles. Can you move your car, please? MILES (O.S.) What for? RAUL The painters got to put the truck in, and you didn’t park too good. MILES (O.S.) (a sigh, then --) Yeah, hold on. He closes the door with a SLAM. EXT. HIDEOUS APARTMENT COMPLEX - DAY SUPERIMPOSE -- SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA Wearing only underwear, a bathrobe, and clogs, MILES RAYMOND comes out of his unit and heads toward the street. He passes some SIX MEXICANS, ready to work. 2. He climbs into his twelve-year-old convertible SAAB, parked far from the curb and blocking part of the driveway. The car starts fitfully. As he pulls away, the guys begin backing up the truck. EXT. STREET - DAY Miles rounds the corner and finds a new parking spot. INT. CAR - CONTINUOUS He cuts the engine, exhales a long breath and brings his hands to his head in a gesture of headache pain or just plain anguish. He leans back in his seat, closes his eyes, and soon nods off. -

Slice Proof Swing Tony Finau Take the Flagstick Out! Hot List Golf Balls

VOLUME 4 | ISSUE 1 MAY 2019 `150 THINK YOUNG | PLAY HARD PUBLISHED BY SLICE PROOF SWING TONY FINAU TAKE THE FLAGSTICK OUT! HOT LIST GOLF BALLS TIGER’S SPECIAL HERO TRIUMPH INDIAN GREATEST COMEBACK STORY OPEN Exclusive Official Media Partner RNI NO. HARENG/2016/66983 NO. RNI Cover.indd 1 4/23/2019 2:17:43 PM Roush AD.indd 5 4/23/2019 4:43:16 PM Mercedes DS.indd All Pages 4/23/2019 4:45:21 PM Mercedes DS.indd All Pages 4/23/2019 4:45:21 PM how to play. what to play. where to play. Contents 05/19 l ArgentinA l AustrAliA l Chile l ChinA l CzeCh republiC l FinlAnd l FrAnCe l hong Kong l IndIa l indonesiA l irelAnd l KoreA l MAlAysiA l MexiCo l Middle eAst l portugAl l russiA l south AFriCA l spAin l sweden l tAiwAn l thAilAnd l usA 30 46 India Digest Newsmakers 70 18 Ajeetesh Sandhu second in Bangladesh 20 Strong Show By Indians At Qatar Senior Open 50 Chinese Golf On The Rise And Yes Don’t Forget The 22 Celebration of Women’s Golf Day on June 4 Coconuts 54 Els names Choi, 24 Indian Juniors Bring Immelman, Weir as Laurels in Thailand captain’s assistants for 2019 Presidents Cup 26 Club Round-Up Updates from courses across India Features 28 Business Of Golf Industry Updates 56 Spieth’s Nip-Spinner How to get up and down the spicy way. 30 Tournament Report 82 Take the Flagstick Out! Hero Indian Open 2019 by jordan spieth Play Your Best We tested it: Here’s why putting with the pin in 60 Leadbetter’s Laser Irons 75 One Golfer, Three Drives hurts more than it helps. -

Channel Lineup January 2018

MyTV CHANNEL LINEUP JANUARY 2018 ON ON ON SD HD• DEMAND SD HD• DEMAND SD HD• DEMAND My64 (WSTR) Cincinnati 11 511 Foundation Pack Kids & Family Music Choice 300-349• 4 • 4 A&E 36 536 4 Music Choice Play 577 Boomerang 284 4 ABC (WCPO) Cincinnati 9 509 4 National Geographic 43 543 4 Cartoon Network 46 546 • 4 Big Ten Network 206 606 NBC (WLWT) Cincinnati 5 505 4 Discovery Family 48 548 4 Beauty iQ 637 Newsy 508 Disney 49 549 • 4 Big Ten Overflow Network 207 NKU 818+ Disney Jr. 50 550 + • 4 Boone County 831 PBS Dayton/Community Access 16 Disney XD 282 682 • 4 Bounce TV 258 QVC 15 515 Nickelodeon 45 545 • 4 Campbell County 805-807, 810-812+ QVC2 244• Nick Jr. 286 686 4 • CBS (WKRC) Cincinnati 12 512 SonLife 265• Nicktoons 285 • 4 Cincinnati 800-804, 860 Sundance TV 227• 627 Teen Nick 287 • 4 COZI TV 290 TBNK 815-817, 819-821+ TV Land 35 535 • 4 C-Span 21 The CW 17 517 Universal Kids 283 C-Span 2 22 The Lebanon Channel/WKET2 6 Movies & Series DayStar 262• The Word Network 263• 4 Discovery Channel 32 532 THIS TV 259• MGM HD 628 ESPN 28 528 4 TLC 57 557 4 STARZEncore 482 4 ESPN2 29 529 Travel Channel 59 559 4 STARZEncore Action 497 4 EVINE Live 245• Trinity Broadcasting Network (TBN) 18 STARZEncore Action West 499 4 EVINE Too 246• Velocity HD 656 4 STARZEncore Black 494 4 EWTN 264•/97 Waycross 850-855+ STARZEncore Black West 496 4 FidoTV 688 WCET (PBS) Cincinnati 13 513 STARZEncore Classic 488 4 Florence 822+ WKET/Community Access 96 596 4 4 STARZEncore Classic West 490 Food Network 62 562 WKET1 294• 4 4 STARZEncore Suspense 491 FOX (WXIX) Cincinnati 3 503 WKET2 295• STARZEncore Suspense West 493 4 FOX Business Network 269• 669 WPTO (PBS) Oxford 14 STARZEncore Family 479 4 FOX News 66 566 Z Living 636 STARZEncore West 483 4 FOX Sports 1 25 525 STARZEncore Westerns 485 4 FOX Sports 2 219• 619 Variety STARZEncore Westerns West 487 4 FOX Sports Ohio (FSN) 27 527 4 AMC 33 533 FLiX 432 4 FOX Sports Ohio Alt Feed 601 4 Animal Planet 44 544 Showtime 434 435 4 Ft. -

HIT IT LIKE HIDEKI by Ron Kaspriske by Photograph by Firstlastname

HIT IT LIKE HIDEKI by ron kaspriske S T OP. & GO! gutter credit tk gutter credit 56 golfdigest.com | august 2018 Photograph by First Lastname Photographs by Finlay Mackay ubba watson lets both feet shift toward the target as he smashes the ball, and Jim Furyk loops his club from a nearly upright orientation at the top of the swing to one of the best impact positions in golf. Jordan Spieth’s left Belbow juts toward the target through impact, and Dustin Johnson bows his left wrist as he takes the club back. If you’re learning how to swing or just taking a lesson to improve, the idiosyncracies of many of the game’s best players probably wouldn’t be things an instructor would try to get you to copy. They’re too individualistic. But that’s not the case when it comes to the signature feature of Hideki Matsuyama’s swing—it just might be the thing you need to hit better shots. “There’s a distinct pause between his backswing and downswing. Everything stops for a split second,” says Jim McLean, one of Golf Digest’s 50 Best Teachers. “It allows him to get in the same great position at the top and sync up his downswing beautifully. The pause makes it special.” ▶ ▶ ▶ tk gutter credit tk gutter credit 58 golfdigest.com | august 2018 Photograph by First Lastname Photograph by First Lastname month 2018 | golfdigest.com 59 how the pause came to be ▶ As noticeable as the interlude is, and as much as on the range with hideki it has helped Matsuyama’s swing—the 26-year- old has been 10th or better in the World Golf Ever wonder how the best players Ranking since the fall of 2016—would you be- prepare for a round? You can join Hideki lieve he’s not doing it on purpose? ▶ “I’m not try- Matsuyama as he goes through his pre- ing to stop,” Matsuyama says through a Japanese round warm-up by checking out our new interpreter. -

2020-21 Men's Golf

U NIVERSITY OF I LLINOIS 2020-21 MEN’S GOLF TABLE OF CONTENTS Head Coach Mike Small ����������������������������������������2-7 Assistant Coach Justin Bardgett / Director of Operations Jackie Szymoniak���8 Michael Feagles �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 9-10 Giovanni Tadiotto . .11-12 Brendan O’Reilly � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �13 Luke Armbrust� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �14 Adrien Dumont de Chassart ��������������������������������������15 Tommy Kuhl ��������������������������������������������������16 Jerrry Ji ������������������������������������������������������17 Nico Lang ����������������������������������������������������18 Piercen Hunt ��������������������������������������������������19 Olympia Fields Country Club Fighting Illini Invitational �����������������20 2019-20 Review . 21-22 2019-20 Results/Statistics������������������������������������23-27 Team Records ����������������������������������������������28-29 Individual Records . 30-32 Big Ten Championships Results �����������������������������������33 2020-21 ILLINOIS MEN’S GOLF ROSTER NCAA Regional & NCAA Championships Results�����������������������34 Name Year Hometown / Previous School Individual Honors �������������������������������������������34-36 Luke Armbrust Jr� Wheaton, Illinois/St� Francis All-Time Letterwinners ���������������������������������������37-38 Adrien Dumont -

List of Directv Channels (United States)

List of DirecTV channels (United States) Below is a numerical representation of the current DirecTV national channel lineup in the United States. Some channels have both east and west feeds, airing the same programming with a three-hour delay on the latter feed, creating a backup for those who missed their shows. The three-hour delay also represents the time zone difference between Eastern (UTC -5/-4) and Pacific (UTC -8/-7). All channels are the East Coast feed if not specified. High definition Most high-definition (HDTV) and foreign-language channels may require a certain satellite dish or set-top box. Additionally, the same channel number is listed for both the standard-definition (SD) channel and the high-definition (HD) channel, such as 202 for both CNN and CNN HD. DirecTV HD receivers can tune to each channel separately. This is required since programming may be different on the SD and HD versions of the channels; while at times the programming may be simulcast with the same programming on both SD and HD channels. Part time regional sports networks and out of market sports packages will be listed as ###-1. Older MPEG-2 HD receivers will no longer receive the HD programming. Special channels In addition to the channels listed below, DirecTV occasionally uses temporary channels for various purposes, such as emergency updates (e.g. Hurricane Gustav and Hurricane Ike information in September 2008, and Hurricane Irene in August 2011), and news of legislation that could affect subscribers. The News Mix channels (102 and 352) have special versions during special events such as the 2008 United States Presidential Election night coverage and during the Inauguration of Barack Obama. -

Special Commemorative 2008 SPGA Edition History of the Senior PGA Championship

Jay Haas Captures 2008 Senior PGA Title The field was impressive, including players. The weather ended up to On Sunday afternoon, it was 15 major champions, with 9 Senior be perfect. Local golf hero, Jeff Slu- Jay Haas who won the right to hold PGA titles, 8 Masters titles, 6 US man made his Senior Champion- the Alfred S. Bourne Trophy with Opens, 5 British Opens and, 2 ship debut and put on an amazing a 7 over par, beating out Bernhard PGA Championship titles between performance for the huge crowds Langer on the last hole by one them; 7 Ryder Cup captains, and that followed him every day. Brian stroke. Bill Britton was the win- 6 Golf Hall of Fame members and Whitcomb, President of the PGA of ning club professional with a 14 representatives of 15 countries. America, summed it up on Sunday, over par. The golf course was pristine, giv- “It doesn’t get any better than this! ing a tremendous challenge to the Thank you Oak Hill.” Bill Britton, Winning Club Professional Jeff Sluman, hometown favorite, made his Senior Tour debut. Jay Haas, Winner of the 69th Senior PGA Championship Special Commemorative 2008 SPGA Edition History of the Senior PGA Championship The all-time great amateur player Bobby Jones, along with his good friend Alfred S. Bourne, organized the first Senior PGA Champion- ship in 1937 at Augusta National Golf Club. Bourne who was a co- founder and benefactor of Augusta National donated the large silver Champions Cup still known as the Alfred S. Bourne Trophy. -

XFINITY® TV Channel Lineup

XFINITY® TV Channel Lineup Somerville, MA C-103 | 05.13 51 NESN 837 A&E HD 852 Comcast SportsNet HD Limited Basic 52 Comcast SportsNet 841 Fox News HD 854 Food Network HD 54 BET 842 CNN HD 855 Spike TV HD 2 WGBH-2 (PBS) / HD 802 55 Spike TV 854 Food Network HD 858 Comedy Central HD 3 Public Access 57 Bravo 859 AMC HD 859 AMC HD 4 WBZ-4 (CBS) / HD 804 59 AMC 863 Animal Planet HD 860 Cartoon Network HD 5 WCVB-5 (ABC) / HD 805 60 Cartoon Network 872 History HD 862 Syfy HD 6 NECN 61 Comedy Central 905 BET HD 863 Animal Planet HD 7 WHDH-7 (NBC) / HD 807 62 Syfy 906 HSN HD 865 NBC Sports Network HD 8 HSN 63 Animal Planet 907 Hallmark HD 867 TLC HD 9 WBPX-68 (ION) / HD 803 64 TV Land 910 H2 HD 872 History HD 10 WWDP-DT 66 History 901 MSNBC HD 67 Travel Channel 902 truTV HD 12 WLVI-56 (CW) / HD 808 13 WFXT-25 (FOX) / HD 806 69 Golf Channel Digital Starter 905 BET HD 14 WSBK myTV38 (MyTV) / 186 truTV (Includes Limited Basic and 906 HSN HD HD 814 208 Hallmark Channel Expanded Basic) 907 Hallmark HD 15 Educational Access 234 Inspirational Network 908 GMC HD 16 WGBX-44 (PBS) / HD 801 238 EWTN 909 Investigation Discovery HD 251 MSNBC 1 On Demand 910 H2 HD 17 WUNI-27 (UNI) / HD 816 42/246 Bloomberg Television 18 WBIN (IND) / HD 811 270 Lifetime Movie Network 916 Bloomberg Television HD 284 Fox Business Network 182 TV Guide Entertainment 920 BBC America HD 19 WNEU-60 (Telemundo) / 199 Hallmark Movie Channel HD 815 200 MoviePlex 20 WMFP-62 (IND) / HD 813 Family Tier 211 style. -

Channel Lineup

† 49 ABC Family 122 Nicktoons TV 189 VH1 Soul 375 MAX Latino Southern † † 50 Comedy Central 123 Nick Jr. 190 FX Movie Channel 376 5 StarMAX † † Westchester 51 E! 124 Teen Nick 191 Hallmark Channel 377 OuterMAX † † February 2014 52 VH1 125 Boomerang 192 SundanceTV 378 Cinemax West † † 53 MTV 126 Disney Junior 193 Hallmark Movie Channel 379 TMC On Demand 2 WCBS (2) New York (CBS) † † 54 BET 127 Sprout 195 MTV Tr3s 380 TMC Xtra 3 WPXN (31) New York (ION) 55 MTV2 131 Kids Thirteen 196 FOX Deportes 381 TMC West 4 WNBC (4) New York (NBC) † 2† † 56 FOX Sports 1 132 WLIW World 197 mun 382 TMC Xtra West 5 WNYW (5) New York (FOX) 57 Animal Planet 133 WLIW Create 198 Galavisión 400-413 Optimum Sports & 6 WRNN (62) Kingston (IND) † † 58 truTV 134 Trinity Broadcasting Network 199 Vme Entertainment Pak 7 WABC (7) New York (ABC) 59 CNN Headline News† 135 EWTN 291 The Jewish Channel On Demand 414 Sports Overflow 8 WXTV (41) Paterson 60 SportsNet New York 136 Daystar 300 HBO On Demand 415-429 Seasonal Sports Packages (Univisión)† 61 News 12 Traffic & Weather 137 Telecare 301 HBO Signature 430 NBA TV 9 My9 New York (MNT-WWOR) 62 The Weather Channel 138 Shalom TV 302 HBO Family 432-450 Seasonal Sports Packages 10 WLNY (55) Riverhead (IND) † 64 Esquire Network 140 ESPN Classic 303 HBO Comedy 460 Sports Overflow 2 11 WPIX (11) New York (CW) † † 66 C-SPAN 2 141 ESPNEWS 304 HBO Zone 461-465 Optimum Sports & 12 News 12 Westchester † † 67 Turner Classic Movies 142 FXX 305 HBO Latino Entertainment Pak 13 WNET (13) New York (PBS) Channel Lineup Channel † 68 Religious -

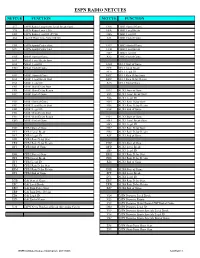

Espn Radio Netcues

ESPN RADIO NETCUES NETCUE FUNCTION NETCUE FUNCTION 237 ESPN Radio Long-Form Local Break Start EG6 CBB1 Start of Game T98 ESPN Radio Liner (:10) EFA CBB1 Local Break EID ESPN Radio Legal ID (59:50) EB6 CBB1 Legal ID 864 Top Of Hour Time Sync (00:00) EZ1 CBB1 End of Game I3M ESPN SportsCenter Start EG9 CBB2 Start of Game SCE ESPN SportsCenter End EFB CBB2 Local Break EB7 CBB2 Legal ID EG5 NBA1 Start of Game EZ2 CBB2 End of Game ES1 NBA1 Local Break Start ES2 NBA1 Legal ID EGD NFL1 Start of Game ESD NBA1 End of Game EFE NFL1 Local Break EC0 NFL1 Legal ID EG1 MLB1 Start of Game ERT NFL1 Rain Delay Start ES3 MLB1 Local Break Start ERV NFL1 Rain Delay Rejoin ES4 MLB1 Legal ID EZ5 NFL1 End of Game ER3 MLB1 Rain Delay Start ER4 MLB1 Rain Delay Rejoin EG3 AUX1 Start of Game ESC MLB1 End of Game ES5 AUX1 Local Break Start ES6 AUX1 Legal ID EG2 MLB2 Start of Game ER5 AUX1 Rain Delay Start EB2 MLB2 Local Break Start ER6 AUX1 Rain Delay Rejoin EB3 MLB2 Legal ID ESE AUX1 End of Game ER1 MLB2 Rain Delay Start ER2 MLB2 Rain Delay Rejoin EG4 AUX2 Start of Game ESG MLB2 End of Game EB4 AUX2 Local Break Start EB5 AUX2 Legal ID EG7 CFB1 Start of Game ER7 AUX2 Rain Delay Start EF1 CFB1 Local Break ER8 AUX2 Rain Delay Rejoin EF2 CFB1 Legal ID ESF AUX2 End of Game ERJ CFB1 Rain Delay Start ERK CFB1 Rain Delay Rejoin EGC AUX3 Start of Game EF3 CFB1 End of Game EFD AUX3 Local Break EB9 AUX3 Legal ID EG8 CFB2 Start of Game ERQ AUX3 Rain Delay Start EF4 CFB2 Local Break ERS AUX3 Rain Delay Rejoin EF5 CFB2 Legal ID EZ4 AUX3 End of Game ERL CFB2 Rain Delay Start -

Brazil Brazil

Global Sports Media Yearbook 2010 Brazil Brazil Population Population 198,739,269198,739,269 Cable TV subs 4.2m GDP/PPP GDP/PPP $2,030bn$1,998bn Satellite TV subs 2.4m GDP per capital GDP per capita $10,300$10,200 Broadband subs 2m TVHH TV Households 53 million53m Mobile broadband 300,000 Total pay-TV Total pay-TV 6.3 million6.9m Digital switchover June 2016 The Brazilian broadcasting market has long been dominated by The bigger challenge to Globo will nevertheless come from pay- the powerful Organizações Globo media group. The company television, which has a penetration rate of just over 10 per cent operates a nation-wide free-to-air network and a range of pay- – low by Latin American standards. Rising competition from new television channels and pay-per-view services. It also holds minority players, including Spain’s Telefônica and Mexico’s Telmex, as well stakes in the leading cable and digital satellite platforms and, as as local telecoms operators Embratel and Oi, will almost certainly if that weren’t enough, it has a wide range of top domestic and be felt in the next few years. international media rights to top soccer properties – a key draw in Even the government has had a go at reducing Globo’s soccer-mad Brazil, due to host the Fifa World Cup in 2014. dominance; in 2006, the competition authority, the CADE, ruled Globo’s rivals have tried hard in recent years to whittle down its that Globo could not maintain exclusive control over top domestic huge market share, and to some extent have succeeded, with and international soccer rights, a decision which led Globo to Rede Record in particular increasing its audience share through a sublicense its popular sports channels, SporTV and SporTV2, to successful mix of soap operas and top sport – including the 2010 rival pay-TV operators. -

ING Media Awards-Previous Results

ING Media Awards-Previous Results 2015 ING Media Awards (Sponsored by Bridgestone Golf, Chase54, Nexbelt, PGA Golf Exhibitions, Zero Friction Golf) BOOK AUTHOR 1st Place: David B. Irwin (“The Last Caddy”) Outstanding Achievers: Tony Dear (“The Story Of Fifty Holes”); Rolando Merulo (“The Italian Summer”); Joel Zuckerman (“Golfers Giving Back”). BUSINESS WRITING 1st Place: Tony Leodora, Golfstyles Magazine (“Your New Club in the 21st Century”). Outstanding Achievers: Elisa Gaudet, Huffington Post (“5 Golf Business Success Stories”); Sally J. Sportsman, Golf Range Magazine (“Design Your Range As If Money Were No Object”); Ed Travis, The A Position (“Competition For Tee Times”). COMPETITION WRITING 1st Place: Mike Kern, Philadelphia Daily News (“History Major”) Outstanding Achievers: Ann Liguori, CBSNY.com (“Dramatic Finish Will Dominate Memories of 2015 US Open”); Jeff Ritter, Golf.Com (“Tiger Woods Misses The Cut At British Open – Now What?”); Gary Van Sickle, Golf.Com (“Stricker Plays His Last Major…Maybe”). EQUIPMENT & APPAREL WRITING 1st Place: Gary Van Sickle, Sports Illustrated (“Saddle Up - The Future of Putting”). Outstanding Achievers: Tony Dear, Today’s Golfer (UK) (“A Smarter Future”); Ed Travis, Golf Oklahoma (“Pro V1 or Pro V1X) OPINION/EDITORIAL 1st Place: Gary Van Sickle, Golf.Com (“What’s Wrong With Tiger?”). Outstanding Achievers: Tony Dear, Cybergolf.com (“Did The Chambers Bay Experiment Work?”); Ann Liguori, CBSNY.com (“Jason Day's US Open Performance One For The Ages”); Jeff Neuman, The Met Golfer (“Hear The Words, Not The Buzz”); Jeff Ritter, Sports Illustrated (“The Best Deal In Golf”). PHOTOGRAPHY 1st Place: Elisa Gaudet, New England Golf Monthly (“Abaco Golf Club”). Outstanding Achiever: Jim Krajicek, The Met Golfer (“A Star Is Born”).