Planning for Coptic Egyptian Immigrant Integration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Arab Spring: a Revolution for Egyptian Emigration? Delphine Pagès-El Karoui

The Arab Spring: A Revolution for Egyptian Emigration? Delphine Pagès-El Karoui To cite this version: Delphine Pagès-El Karoui. The Arab Spring: A Revolution for Egyptian Emigration?. Revue Eu- ropeenne des Migrations Internationales, Université de Poitiers, 2015, Migrations au Maghreb et au Moyen-Orient : le temps des révolutions 31 (3-4). hal-01548298 HAL Id: hal-01548298 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01548298 Submitted on 27 Jun 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. This is the translation of an article published in French, in Revue Européenne des Migrations internationales, 2015, vol. 31, n°3/4. Abstract: This paper examines the impacts of the Arab revolutions on Egyptian emigration, attending to the diverse temporalities of political life in the country and the region between 2011 and 2015. New flows, new reasons for migration (instability, insecurity), and new transnational practices (overseas voting) have arisen. During the postrevolutionary period, transnational practices gained momentum, a diaspora began to emerge (though this process was soon cut short), and Egyptian communities abroad became more visible. Transnational connections between Egyptians as well as migrants’ or their descendants’ links with Egypt were strengthened. -

Invisiblity and Racial Ambiguity of Arab American Women

INVISIBLITY AND RACIAL AMBIGUITY OF ARAB AMERICAN WOMEN “What Are You?” Racial Ambiguity, Belonging, and Well-being Among Arab American Women Laila Abdel-Salam Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 INVISIBLITY AND RACIAL AMBIGUITY OF ARAB AMERICAN WOMEN © 2021 Laila Abdel-Salam All Rights Reserved INVISIBLITY AND RACIAL AMBIGUITY OF ARAB AMERICAN WOMEN Abstract “What Are You?” Racial Ambiguity, Belonging, and Well-being Among Arab American Women Laila Abdel-Salam Even within counseling psychology’s multicultural literature, attention to individuals of Arab descent remains narrow (Awad, 2010; Abdel-Salam, 2019). Despite counseling psychologists’ goals regarding multiculturally proficiency, the dearth of systematic empirical research on the counseling of Arab Americans remains conspicuous. The present study attempts to fill this gap by exploring the impact of racial ambiguity and legal invisibility on Arab Americans’ sense of belonging and well-being. This exploratory consensual qualitative research (CQR) investigation analyzed interview data from 13 non-veiled Arab American women. The interview probed their reactions to Arab Americans’ legal invisibility in the US, queried how they believed White people versus people of color racially perceived them, and examined their subsequent emotional responses and coping strategies. The study’s results revealed participants’ feelings of invisibility, invalidation and hurt when they were not recognized as a person of color (PoC) and brought the participants’ perpetual experience of exclusion to the forefront. The results not only have implications for professional practice and education but also for policy. -

A Case Study of Arabic Heritage Learners and Their Community

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) “SPEAK AMERICAN!” OR LANGUAGE, POWER AND EDUCATION IN DEARBORN, MICHIGAN: A CASE STUDY OF ARABIC HERITAGE LEARNERS AND THEIR COMMUNITY BY KENNETH KAHTAN AYOUBY Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Education, the University of Port Elizabeth, in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor Educationis Promoter: Prof. Susan van Rensburg, Ph.D. The University of Port Elizabeth November 2004 ABSTRACT This study examines the history and development of the “Arabic as a foreign language” (AFL) programme in Dearborn Public Schools (in Michigan, the United States) in its socio-cultural and political context. More specifically, this study examines the significance of Arabic to the Arab immigrant and ethnic community in Dearborn in particular, but with reference to meanings generated and associated to Arabic by non- Arabs in the same locale. Although this study addresses questions similar to research conducted on Arab Americans in light of anthropological and sociological theoretical constructs, it is, however, unique in examining education and Arabic pedagogy in Dearborn from an Arab American studies and an educational multi-cultural perspective, predicated on/and drawing from Edward Said’s critique of Orientalism, Paulo Freire’s ideas about education, and Henry Giroux’s concern with critical pedagogy. In the American mindscape, the "East" has been the theatre of the exotic, the setting of the Other from colonial times to the present. The Arab and Muslim East have been constructed to represent an opposite of American culture, values and life. -

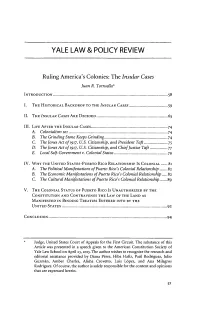

Ruling America's Colonies: the Insular Cases Juan R

YALE LAW & POLICY REVIEW Ruling America's Colonies: The Insular Cases Juan R. Torruella* INTRODUCTION .................................................................. 58 I. THE HISTORICAL BACKDROP TO THE INSULAR CASES..................................-59 11. THE INSULAR CASES ARE DECIDED ......................................... 65 III. LIFE AFTER THE INSULAR CASES.......................... .................. 74 A. Colonialism 1o ......................................................... 74 B. The Grinding Stone Keeps Grinding........... ....... ......................... 74 C. The Jones Act of 1917, U.S. Citizenship, and President Taft ................. 75 D. The Jones Act of 1917, U.S. Citizenship, and ChiefJustice Taft ............ 77 E. Local Self-Government v. Colonial Status...........................79 IV. WHY THE UNITED STATES-PUERTO Rico RELATIONSHIP IS COLONIAL...... 81 A. The PoliticalManifestations of Puerto Rico's Colonial Relationship.......82 B. The Economic Manifestationsof Puerto Rico's ColonialRelationship.....82 C. The Cultural Manifestationsof Puerto Rico's Colonial Relationship.......89 V. THE COLONIAL STATUS OF PUERTO Rico Is UNAUTHORIZED BY THE CONSTITUTION AND CONTRAVENES THE LAW OF THE LAND AS MANIFESTED IN BINDING TREATIES ENTERED INTO BY THE UNITED STATES ............................................................. 92 CONCLUSION .................................................................... 94 * Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. The substance of this Article was presented in -

Extensions of Remarks

November 16, 1989 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 29607 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS UNDERESTIMATING THE COST creases under statehood which differ radi exemption that would be precipitously OF STATEHOOD IN PLEBISCITE cally from those of the Energy and Natural ended · by the advent of statehood. The ON PUERTO RICO'S FUTURE Resources Committee Report. The cumula elimination of federal tax exemption would tive difference in the two estimates over have at least three major effects upon the just four years is $5.711 billion, a significant island's economy. First, it would deprive the HON. JAIME B. FUSTER sum that brings up estimates of additional local government of most of the funds it OF PUERTO RICO federal expenditures for Puerto Rico to now has, largely diminishing its role as the IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES $9.33 billion in the first 4 years of state main support of the Puerto Rican economy. hood. Exemption from federal taxes has permit Thursday, November 16, 1989 Even CBO's very broad assessment is not ted Puerto Rico to support a large public Mr. FUSTER. Mr. Speaker, once again I call yet complete. For one, the Congressional sector providing vital public services and to the attention of my colleagues develop Research Service had identified for us an employing more than a third of the work ments in the ongoing legislative process for a additional $107,778,000 which Puerto Rico force. Financing for this huge public sector congressionally sanctioned political status would have received in Title I education comes mainly from Puerto Rico income plebiscite in Puerto Rico. -

The Arab Uprisings and the Politics of Contention Beyond Borders: the Case of Egyptian Communiites in the United States’

The Arab Uprisings and The Politics of Contention Beyond Borders: The Case of Egyptian Communiites in the United States’ Tamirace Fakhoury Mashriq & Mahjar: Journal of Middle East and North African Migration Studies, Volume 5, Number 1, 2018, (Article) Published by Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/778398/summary [ Access provided at 28 Sep 2021 17:10 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] © Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies 2018 72 Tamirace Fakhoury INTRODUCTION The field of transnational migrant activism I has generated important insights into the ways in which Arab communities around the world have used exilic spheres to transnationalize dissent and mobilize against their authoritarian homelands.' Still, migration scholars do not so far dispose of sufficient cross comparative data to assess the impact of Arab emigration waves on Arab political systems.' In 20ll, the anti-regime uprisings, which have spurred Arab communities abroad to participate in their homeland's affairs,4 provide exceptional terrain to study Arab transnational politics and their effects.' This article seeks to advance understanding of the participation of Arab migrant communities in the 2011 anti-regime uprisings and the interactive processes that impact their mobilization on the ground. Building on the 'iconic' Egyptian uprising that inspired contention in other Arab polities,' it draws on the case study of Egyptian communities in the United States and maps the transnational practices in which Egyptians in the US engaged to sustain political ties with Egypt in the period between 25 january and 11 February 2011 and its direct aftermath. -

2009-2010 Slos by Department

CMS System http://diogenes.fhda.edu/cms/slo.admin.php Bugs? Errors? Comments? Student Learning Outcome Administration System Return to Options Learning Outcomes Detail Report by Department View More Reports 15 of 17 Course IDs for ACTG in the Business and Social Sciences Division 2009-2010 have SLO's. Course ID Title SLO's ACTG 1A FINANCIAL ACCOUNTING I SLO 1. Explain financial accounting terminology, concepts, principles, and frameworks. [SLO1a: Theory]. ILO 1. 1. Communication 2. Creative, critical and analytical thinking SLO 2. Perform related calculations and demonstrate the ability to use methods and /or procedures to solve financial accounting problems. [SLO1b: Application] ILO 2. 3. Computation ACTG 1B FINANCIAL ACCOUNTING II SLO 1. Explain financial accounting terminology, concepts, principles, and frameworks. [SLO1a: Theory]. ILO 1. 1. Communication 2. Creative, critical and analytical thinking SLO 2. Perform related calculations and demonstrate the ability to use methods and /or procedures to solve financial accounting problems. [SLO1b: Application] ILO 2. 3. Computation ACTG 1C MANAGERIAL ACCOUNTING SLO 1. Explain managerial accounting terminology, concepts, principles, and frameworks. [SLO1a: Theory]. ILO 1. 1. Communication 2. Creative, critical and analytical thinking SLO 2. Perform related calculations and demonstrate the ability to use methods and /or procedures to solve managerial accounting problems. [SLO1b: Application] ILO 2. 3. Computation ACTG 51A INTERMEDIATE ACCOUNTING I SLO 1. Explain intermediate financial accounting terminology, concepts, principles, and frameworks.[SLO1a: Theory]. SLO 2. Perform related calculations and demonstrate the ability to use methods and /or procedures to solve intermediate financial accounting problems [SLO1b: Application] ACTG 51B INTERMEDIATE ACCOUNTING II SLO 1. -

A Study of Yussef El Guindi's Drama

Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies Copyright 2020 2020, Vol. 7, No. 3, 177-199 ISSN: 2149-1291 http://dx.doi.org/10.29333/ejecs/458 Combating 9/11 Negative Images of Arabs in American Culture: A Study of Yussef El Guindi’s Drama Mahmoud F. Alshetawi1 The University of Jordan Abstract: This study intends to examine the dramatic endeavours of Arab American playwrights to make their voices heard through drama, performance, and theatre in light of transnationalism and diaspora theory. The study argues that Arab American dramatists and theatre groups attempt to counter the hegemonic polemics against Arabs and Muslims, which have madly become characteristic of contemporary American literature and media following 9/11. In this context, this study examines Yussef El Guindi, an Egyptian-American, and his work. El Guindi has devoted most of his plays to fight the stereotypes that are persistently attributed to Arabs and Muslims, and his drama presents issues relating to identity formation and what this formation means to be Arab American. A scrutiny of these plays shows that El Guindi has dealt with an assortment of topics and issues all relating to the stereotypes of Arab Americans and the Middle East. These issues include racial profiling and surveillance, stereotypes of Arabs and Muslims in the cinema and theatre, and acculturation and clash of cultures. Keywords: acculturation, Arab American, diaspora, drama, identity formation, racial profiling, stereotypes theatre. Over the ages, Arabs and Muslims have been denigrated and stereotypically represented in almost all outlets of Western media: the cinema, literature and the press and other channels of expression. -

Coptic Studies Abstracts

ABSTRACTS THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR COPTIC STUDIES Hosted by Claremont Graduate University and St. Shenouda The Archimandrite Coptic Society JULY 25-30, 2016 Abstracts of the Papers Presented at the Eleventh International Congress of Coptic Studies (Claremont, July 25-30, 2016) The listing of the abstracts, starting on page 6, in this publication is arranged in alphabetical order of the speaker's last name. Beside the name, the following are included: academic affiliation, email address, paper title, and the submitted abstract. The abstracts are preceded by a list of the panels and specific sessions included in the program with panel/session description and names and paper titles of its respective participants. DESCRIPTION OF THE PANELS/SPECIAL SESSIONS Panel Title: Prospects and studies for the reconstruction and edition of the Coptic Bible (CB) Panel Chairs: Dr. Frank Feder [email protected], and Dr. Siegfried Richter [email protected] Description: During the panel the two large scale projects for the edition of the Coptic New (Münster: http://egora.uni-muenster.de/intf/index_en.shtml) and Old (Göttingen: http://coptot.manuscriptroom.com/home) Testament will present the actual state of their work and the possibilities for the Coptological community to collaborate with them. The panel invites all colleagues to present new projects or project ideas concerning the Coptic Bible as well as contributions to all aspects of the manuscripts and the textual transmission. Participants: (in alphabetical order) Dr. Christian Askeland. Orthodoxy and Heresy in the Digitization of the Bible Prof. Heike Behlmer. Paul de Lagarde, Agapios Bsciai and the Edition of the Coptic Bible Dr. -

The Effects of Acculturation Level and Parenting Styles on Parent-Child Relationships Within the Egyptian Culture" (2000)

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2000 The effects of acculturation level and parenting styles on parent- child relationships within the Egyptian culture Jacqueline Sawires Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Multicultural Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Sawires, Jacqueline, "The effects of acculturation level and parenting styles on parent-child relationships within the Egyptian culture" (2000). Theses Digitization Project. 1708. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/1708 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EFFECTS OF ACCULTURATION LEVEL AND PARENTING STYLES ON PARENT-CHILD RELATIONSHIPS WITHIN THE EGYPTIAN CULTURE A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Social Work ;. ; ■ ■ V ' by. ■ ' Jacqueline Sawires June 2000 THE EFFECTS OF ACCULTURATION LEVEL AND PARENTING STYLES ON PARENT-CHILD RELATIONSHIPS WITHIN THE EGYPTIAN CULTURE A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Jacqueline Sawires June 2000 Approved by: Dr. RosemarsHMCCaslin, Chair Ddte Research SeWence Date ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between the parental level of acculturation and parenting styles on parent/child conflict among Egyptians since no research has been done in this area on this population. -

Complete Dissertation

VU Research Portal Blessed is Egypt my People Klempner, L.J. 2016 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Klempner, L. J. (2016). Blessed is Egypt my People: Recontextualizing Coptic Identity outside of Egypt. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT Blessed is Egypt my People RECONTEXTUALIZING COPTIC IDENTITY OUTSIDE OF EGYPT ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graAd Doctor AAn de Vrije Universiteit AmsterdAm, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. V. SubrAmaniAm, in het openbAAr te verdedigen ten overstAAn vAn de promotiecommissie van de Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen op maAndAg 19 december 2016 om 11.45 uur in de aulA van de universiteit, De BoelelAAn 1105 door Levi JoshuA Klempner geboren te Hadera, Israël promotor: prof.dr. -

The Political Participation of the Diaspora of the Middle East And

C Sarsar, C D’Hondt, MT Di Lenna, A al-Khulidi & S Taha ‘The political participation of the diaspora of the Middle East and North Africa before and after the Arab uprisings’ (2019) 3 Global Campus Human Rights Journal 52-75 https://doi.org/20.500.11825/995 The political participation of the diaspora of the Middle East and North Africa before and after the Arab uprisings Chafic Sarsar, Cedric D’Hondt, Maria Teresia Di Lenna, Ali al- Khulidi and Suhail Taha* Abstract: The role of the Arab diasporas in the political processes of their home countries has changed significantly since the 2011 uprisings. The article aims to analyse these changes and assess the impact that diasporas have had on the democratisation processes of the post-2011 transitions. It does so by looking at examples of both direct and indirect diasporas’ participation in the politics of their home countries during and after the uprisings through mechanisms such as lobbying, campaigning, national dialogue initiatives, and voting in the parliamentary elections. The background to the social, economic and political contributions of the Arab diasporas before 2011 highlights the multiple identities of the diaspora communities abroad as well as the changes to their inclusion from disputed members of the regimes’ opposition to a more active civil society. With the shifting social and political environment of the last decade, the examples demonstrate the important political role that diasporas could play in cooperation and bridge building, both locally and internationally. However, they also demonstrate the obstacles and severe limitations they face in their inclusion in the governments’ transition to democratic governance.