Le Canard Folk: May 7 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electronic Press

Scotland's TANNAHILL WEAVERS “...an especially eloquent mixture of the old and the new...” NEW YORK TIMES Now in their 51st year, the Tannahill Weavers are one of Scotland's premier traditional bands. Their diverse repertoire spans the centuries with fire-driven instrumentals, topical songs, and original ballads and lullabies. Their music demonstrates to old and young alike the rich and varied musical heritage of the Celtic people. These versatile musicians have received worldwide accolades consistently over the years for their exuberant and humorous performances and outstanding recording efforts that seemingly can't get better...yet continue to do just that. ROY GULLANE PHIL SMILLE MALCOLM BUSHBY MIKE KATZ lead vocals, guitar flute, whistles, bodhran, vocals fiddle, vocals, bouzouki highland bagpipes, scottish small pipes, whistles SCOTLAND’S PREMIER TRADITIONAL BAND www.tannahillweavers.com [email protected] Scotland's TANNAHILL WEAVERS Listen: Òrach (listen on Spotify) The Geese in the Bog/The Jig of Slurs (download) Watch: Gordon Duncan Set Johnnie Cope Photos: (click for downloads) SCOTLAND’S PREMIER TRADITIONAL BAND www.tannahillweavers.com [email protected] Scotland's TANNAHILL WEAVERS Press Quotes "…the group has found an especially eloquent mixture of the old and the new. - Stephen Holden, New York Times “The music may be pure old time Celtic, but the drive and enthusiasm are akin to straight ahead rock and roll.” - Winnipeg Free Press “Formed from a Paisley pub session in 1968, seminal trailblazers the Tannahill Weavers now also rank as national treasures.” - Glasgow Celtic Connections 2018 “…the Tannies are the best that Scotland can aspire to (and believe me, that is THE BEST).” - The Living Tradition “Scotland’s Tannahill Weavers play acoustic instruments, but the atmosphere at their shows is electric. -

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

SANDY DENNY UNDER REVIEW: an Independent Critical Analysis, Limited Collectors Edition

SANDY DENNY UNDER REVIEW: An Independent Critical Analysis, Limited Collectors Edition The difference between a critical analysis of {$Sandy Denny} or {$The Velvet Underground} and {$The Rolling Stones} is that with a lot less information available on this extraordinary singer the audience is more limited. The good news is that this edition of the "Under Review" series actually lives up to the documentary status it claims, and does, indeed, hold one's attention and inform better than the {^Green Day: Under Review 1995-2000 The Middle Years}, which is basically a bunch of critics blowing lots of hot air. It seems with these "DVD/Fanzine" type commentaries that the lesser known the subject matter, the better the critique. Denny is a singer that deserves so much more acclaim and study, and this is an excellent starting point, as is the {$Kate Bush} "Under Review", and even the {$David Bowie} {^Under Review 1976-79 Berlin} analysis which concentrates on his dark but fun period. {$Fairport Convention} fiddler {$Dave Swarbrick}, journeyman {$Martin Carthy}, {$Cat Stevens} drummer {$Gerry Conway} of Denny's band, {$Fotheringay} and {$Pentangle}'s {$John Renbourn} contribute as does {$Fairport Convention} biographer {$Patrick Humphries}. That's the extra effort missing in some of these packages which makes this close to two hour presentation all the more interesting. Perhaps more important than the very decent {$Kate Bush} analysis by the {^Under Review} team, there's a "Limited Collector's Edition" with a cardboard slipcover. It's a very classy presentation and a very important history that deserves shelf space in any good library. -

A History of British Music Vol 1

A History of Music in the British Isles Volume 1 A History of Music in the British Isles Other books from e Letterworth Press by Laurence Bristow-Smith e second volume of A History of Music in the British Isles: Volume 1 Empire and Aerwards and Harold Nicolson: Half-an-Eye on History From Monks to Merchants Laurence Bristow-Smith The Letterworth Press Published in Switzerland by the Letterworth Press http://www.eLetterworthPress.org Printed by Ingram Spark To © Laurence Bristow-Smith 2017 Peter Winnington editor and friend for forty years ISBN 978-2-9700654-6-3 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Contents Acknowledgements xi Preface xiii 1 Very Early Music 1 2 Romans, Druids, and Bards 6 3 Anglo-Saxons, Celts, and Harps 3 4 Augustine, Plainsong, and Vikings 16 5 Organum, Notation, and Organs 21 6 Normans, Cathedrals, and Giraldus Cambrensis 26 7 e Chapel Royal, Medieval Lyrics, and the Waits 31 8 Minstrels, Troubadours, and Courtly Love 37 9 e Morris, and the Ballad 44 10 Music, Science, and Politics 50 11 Dunstable, and la Contenance Angloise 53 12 e Eton Choirbook, and the Early Tudors 58 13 Pre-Reformation Ireland, Wales, and Scotland 66 14 Robert Carver, and the Scottish Reformation 70 15 e English Reformation, Merbecke, and Tye 75 16 John Taverner 82 17 John Sheppard 87 18 omas Tallis 91 19 Early Byrd 101 20 Catholic Byrd 108 21 Madrigals 114 22 e Waits, and the eatre 124 23 Folk Music, Ravenscro, and Ballads 130 24 e English Ayre, and omas Campion 136 25 John Dowland 143 26 King James, King Charles, and the Masque 153 27 Orlando Gibbons 162 28 omas -

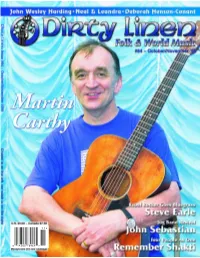

14302 76969 1 1>

11> 0514302 76969 establishment,” he hastened to clarify. “I wish it were called the Legion of Honour, but it’s not.” Still in all, he thinks it’s good for govern- M artin C arthy ments to give cultural awards and is suitably honored by this one, which has previously gone to such outstanding folk performers as Jeannie Robertson. To decline under such circum- stances, he said, would have been “snotty.” Don’t More importantly, he conceives of his MBE as recognition he shares with the whole Call Me folk scene. “I’ve been put at the front of a very, very long queue of people who work hard to make a folk revival and a folk scene,” he said. Sir! “All those people who organized clubs for nothing and paid you out of their own pocket, and fed you and put you on the train the next morning, and put you to bed when you were drunk! What [the government is] doing, is taking notice of the fact that something’s going on for the last more than 40 years. It’s called the folk revival. They’ve ignored it for that long. And someone has suddenly taken notice, and that’s okay. A bit of profile isn’t gonna hurt us — and I say us, the plural, for the folk scene — isn’t gonna hurt us at all.” In the same year as Carthy’s moment of recognition, something happened that did hurt the folk scene. Lal Waterson, Carthy’s sister-in- law, bandmate, near neighbor and close friend, died of cancer. -

Sandy Denny: Under Review (Sexy Intellectual Production)

Sandy Denny: Under Review (Sexy Intellectual Production) This one’s kind of skimpy on the archival footage (often the filmmakers choose to craft impressionistic film collages for songs to compensate), but there is such a dearth of information around about Sandy Denny, easily one of the most mesmeric singers of all time, that I consider this disc absolutely crucial. Fairport Convention vocalist Denny was a tragic folk heroine plagued by insecurity—she never felt comfortable as an artist in the spotlight, preferring to have a band she could lose herself in, (check out her song “Solo” for her lyrical take) — who was nonetheless blessed with a remarkably penetrating voice and superior songwriting talent. (She’s the only “guest vocalist” to ever appear on a Led Zeppelin record, on the Middle-earthy “Battle of Evermore.”) The disc capably illuminates Denny as an artist worthy of rabid cult status, who died under sad circumstances (she fell down a flight of stairs, eventually sinking into a coma), but who was hugely influential on the English folk scene, revered by everyone who knew or played with her. Minor gripe: The commentary by former bandmate Dave Swarbrick is largely garbled, but it appears that this is the way he actually talks—what are you gonna do? A cursory listen to Fairport’s “What We Did On Our Holidays” or “Liege and Lief” should convince anyone with a pair of working ears that the emotionally fragile Denny, with her wounded angel’s voice, was one in a zillion. Natch, the doc glosses over the more unsavory aspects of her character (she could be abusive and her drinking probably contributed to her tumble), but no matter. -

FW May-June 03.Qxd

IRISH COMICS • KLEZMER • NEW CHILDREN’S COLUMN FREE Volume 3 Number 5 September-October 2003 THE BI-MONTHLY NEWSPAPER ABOUT THE HAPPENINGS IN & AROUND THE GREATER LOS ANGELES FOLK COMMUNITY Tradition“Don’t you know that Folk Music is Disguisedillegal in Los Angeles?” — WARREN C ASEY of the Wicked Tinkers THE FOLK ART OF MASKS BY BROOKE ALBERTS hy do people all over the world end of the mourning period pro- make masks? Poke two eye-holes vided a cut-off for excessive sor- in a piece of paper, hold it up to row and allowed for the resump- your face, and let your voice tion of daily life. growl, “Who wants to know?” The small mask near the cen- The mask is already working its ter at the top of the wall is appar- W transformation, taking you out of ently a rendition of a Javanese yourself, whether assisting you in channeling this Wayang Topeng theater mask. It “other voice,” granting you a new persona to dram- portrays Panji, one of the most atize, or merely disguising you. In any case, the act famous characters in the dance of masking brings the participants and the audience theater of Java. The Panji story is told in a five Alban in Oaxaca. It represents Murcielago, a god (who are indeed the other participants) into an arena part dance cycle that takes Prince Panji through of night and death, also known as the bat god. where all concerned are willing to join in the mys- innocence and adolescence up through old age. -

Dissertation Final Submission Andy Hillhouse

TOURING AS SOCIAL PRACTICE: TRANSNATIONAL FESTIVALS, PERSONALIZED NETWORKS, AND NEW FOLK MUSIC SENSIBILITIES by Andrew Neil Hillhouse A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Andrew Neil Hillhouse (2013) ABSTRACT Touring as Social Practice: Transnational Festivals, Personalized Networks, and New Folk Music Sensibilities Andrew Neil Hillhouse Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2013 The aim of this dissertation is to contribute to an understanding of the changing relationship between collectivist ideals and individualism within dispersed, transnational, and heterogeneous cultural spaces. I focus on musicians working in professional folk music, a field that has strong, historic associations with collectivism. This field consists of folk festivals, music camps, and other venues at which musicians from a range of countries, affiliated with broad labels such as ‘Celtic,’ ‘Nordic,’ ‘bluegrass,’ or ‘fiddle music,’ interact. Various collaborative connections emerge from such encounters, creating socio-musical networks that cross boundaries of genre, region, and nation. These interactions create a social space that has received little attention in ethnomusicology. While there is an emerging body of literature devoted to specific folk festivals in the context of globalization, few studies have examined the relationship between the transnational character of this circuit and the changing sensibilities, music, and social networks of particular musicians who make a living on it. To this end, I examine the career trajectories of three interrelated musicians who have worked in folk music: the late Canadian fiddler Oliver Schroer (1956-2008), the ii Irish flute player Nuala Kennedy, and the Italian organetto player Filippo Gambetta. -

Medieval Music for Celtic Harp Pdf Free Download

MEDIEVAL MUSIC FOR CELTIC HARP PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Star Edwards | 40 pages | 01 Jan 2010 | Mel Bay Publications | 9780786657339 | English | United States Medieval Music for Celtic Harp PDF Book Close X Learn about Digital Video. Unde et ibi quasi fontem artis jam requirunt. An elegy to Sir Donald MacDonald of Clanranald, attributed to his widow in , contains a very early reference to the bagpipe in a lairdly setting:. In light of the recent advice given by the government regarding COVID, please be aware of the following announcement from Royal Mail advising of changes to their services. The treble end had a tenon which fitted into the top of the com soundbox. Emer Mallon of Connla in action on the Celtic Harp. List of Medieval composers List of Medieval music theorists. Adam de la Halle. Detailed Description. Monophony was replaced from the fourteenth century by the Ars Nova , a movement that developed in France and then Italy, replacing the restrictive styles of Gregorian plainchant with complex polyphony. Allmand, T. Browse our Advice Topics. Location: optional. The urshnaim may refer to the wooden toggle to which a string was fastened once it had emerged from its hole in the soundboard. Password recovery. The early history of the triangular frame harp in Europe is contested. This word may originally have described a different stringed instrument, being etymologically related to the Welsh crwth. Also: Alasdair Ross discusses that all the Scottish harp figures were copied from foreign drawings and not from life, in 'Harps of Their Owne Sorte'? One wonderful resource is the Session Tunes. -

A Folkrocker's Guide

A FOLKROCKER’S GUIDE – FOLKROCKENS FRAMVEKST 1965–1975 «The eletricifcation of all this stuf was A FOLKROCKER’S GUIDE some thing that was waiting to happen» TO THE UNIVERSE •1965–1975 – Martin Carthy «Folkrock» ble først brukt i 1965 som betegnelse på på Framveksten av folkrock i USA I Storbritania, i motsetning til i USA, kom «folkrock» til amerikanske musikere som The Byrds, den elektrifserte Bob og UK i tiåret 65–75 skapte Dylan, Simon & Garfunkel og – pussig nok – Sonny & Cher. mye av inspirasjonen for den å betegne elektrisk musikk basert på tradisjonell folke- Likevel er det i større grad møtet mellom rock og folkemusikk moderne visebølgen i Norden. musikk. i Storbritannia ca 1969–70 som ble bestemmende for hva vi Vi har bedt Morten Bing om å skrive om dette. Han er kon- på 1970-tallet kom til å legge i begrepet her hjemme. servator ved Norsk Folkemu- som hadde bakgrunn i folkrevivalen, en sanger og en felespiller – Sandy seum og var initiativtaker til men som allerede hadde forlatt Denny og Dave Swarbrick – som MORTEN BING Norges første folkrock gruppe tradisjonell folkemusikk til fordel for begge hadde bakgrunn i den Folque i 1973. egenskrevne låter. britiske folkrevivalen. Det var denne rdet «folke-rock» kombinasjonen, og resultatet, LP’n ble brukt første gang Dylan og Byrds Gruppa har sin kanskje siste På mange måter kan en si at den konsert på Rockefeller i Oslo Liege & Lief (1969), som var begyn- i Billboard 12.06.1965, engelske utviklingen gikk mot- nelsen på den britiske folkrocken. i en artikkel om Bob En viktig katalysator for framveksten 18. -

Fairport Convention Beyond the Ledge (Filmed Live at Cropredy '98) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Fairport Convention Beyond The Ledge (Filmed Live At Cropredy '98) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Folk, World, & Country Album: Beyond The Ledge (Filmed Live At Cropredy '98) Country: UK Released: 1999 Style: Folk Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1379 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1974 mb WMA version RAR size: 1127 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 845 Other Formats: ASF MP4 WMA DXD MOD APE MIDI Tracklist Hide Credits Programme Start : Meet On The Ledge 1 1:50 Arranged By, Performer – Ric SandersWritten-By – Richard Thompson The Lark In The Morning 2 6:14 Arranged By – Leslie*, Pegg*, Conway*, Sanders*, Nicol*Written-By – Traditional Life's A Long Song 3 3:00 Written-By – Ian Anderson Woodworm Swing 4 3:18 Written-By – Ric Sanders Crazy Man Michael 5 5:03 Written-By – Dave Swarbrick, Richard Thompson Dangerous 6 5:29 Written-By – Kristina Olsen The Flow 7 5:13 Arranged By – Ric SandersWritten-By – Chris Leslie Close To You 8 4:24 Written-By – Chris Leslie The Naked Highwayman 9 4:56 Written-By – Steve Tilston The Hiring Fair 10 6:57 Written-By – Ralph McTell Jewel In The Crown 11 3:31 Written-By – Julie Matthews Cosmic Intermezzo 12 5:29 Written-By – Ric Sanders The Bowman's Retreat 13 3:08 Written-By – Ric Sanders Who Knows Where The Time Goes 14 7:11 Featuring – Chris WhileWritten-By – Sandy Denny Come Haste 15 4:36 Arranged By – Leslie*, Pegg*, Conway*, Sanders*, Nicol*Written-By – Trad.* Spanish Main 16 4:40 Written-By – Chris Leslie, Maartin Allcock* John Gaudie 17 6:03 Written-By – Chris Leslie Matty Groves 18a 11:14 Arranged By – Leslie*, Pegg*, Conway*, Sanders*, Nicol*Written-By – Trad.* The Rutland Reel / Sack The Juggler 18b Written-By – Ric Sanders Meet On The Ledge Guest – Anna Ryden*, Chas McDevitt, Chris Knibbs, Chris While, Dave Cousins, David 19 7:10 Hughes , Rabbit*, Maartin Allcock*, P.J.