Diversity and Conservation of Neotropical Mammals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reptile-Like Physiology in Early Jurassic Stem-Mammals

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/785360; this version posted October 10, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Title: Reptile-like physiology in Early Jurassic stem-mammals Authors: Elis Newham1*, Pamela G. Gill2,3*, Philippa Brewer3, Michael J. Benton2, Vincent Fernandez4,5, Neil J. Gostling6, David Haberthür7, Jukka Jernvall8, Tuomas Kankanpää9, Aki 5 Kallonen10, Charles Navarro2, Alexandra Pacureanu5, Berit Zeller-Plumhoff11, Kelly Richards12, Kate Robson-Brown13, Philipp Schneider14, Heikki Suhonen10, Paul Tafforeau5, Katherine Williams14, & Ian J. Corfe8*. Affiliations: 10 1School of Physiology, Pharmacology & Neuroscience, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. 2School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. 3Earth Science Department, The Natural History Museum, London, UK. 4Core Research Laboratories, The Natural History Museum, London, UK. 5European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, France. 15 6School of Biological Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. 7Institute of Anatomy, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. 8Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. 9Department of Agricultural Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. 10Department of Physics, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. 20 11Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht, Zentrum für Material-und Küstenforschung GmbH Germany. 12Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Oxford, OX1 3PW, UK. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/785360; this version posted October 10, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 13Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. 14Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. -

A Vegetation Map of South America

A VEGETATION MAP OF SOUTH AMERICA MAPA DE LA VEGETACIÓN DE AMÉRICA DEL SUR MAPA DA VEGETAÇÃO DA AMÉRICA DO SUL H.D.Eva E.E. de Miranda C.M. Di Bella V.Gond O.Huber M.Sgrenzaroli S.Jones A.Coutinho A.Dorado M.Guimarães C.Elvidge F.Achard A.S.Belward E.Bartholomé A.Baraldi G.De Grandi P.Vogt S.Fritz A.Hartley 2002 EUR 20159 EN A VEGETATION MAP OF SOUTH AMERICA MAPA DE LA VEGETACIÓN DE AMÉRICA DEL SUR MAPA DA VEGETAÇÃO DA AMÉRICA DO SUL H.D.Eva E.E. de Miranda C.M. Di Bella V.Gond O.Huber M.Sgrenzaroli S.Jones A.Coutinho A.Dorado M.Guimarães C.Elvidge F.Achard A.S.Belward E.Bartholomé A.Baraldi G.De Grandi P.Vogt S.Fritz A.Hartley 2002 EUR 20159 EN A Vegetation Map of South America I LEGAL NOTICE Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of the following information. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu.int) Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2002 ISBN 92-894-4449-5 © European Communities, 2002 Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged Printed in Italy II A Vegetation Map of South America A VEGETATION MAP OF SOUTH AMERICA prepared by H.D.Eva* E.E. -

Chronostratigraphy of the Mammal-Bearing Paleocene of South America 51

Thierry SEMPERE biblioteca Y. Joirriiol ofSoiiih Ainorirari Euirli Sciriin~r.Hit. 111. No. 1, pp. 49-70, 1997 Pergamon Q 1‘197 PublisIlcd hy Elscvicr Scicncc Ltd All rights rescrvcd. Printed in Grcnt nrilsin PII: S0895-9811(97)00005-9 0895-9X 11/97 t I7.ol) t o.(x) -. ‘Inshute qfI Human Origins, 1288 9th Street, Berkeley, California 94710, USA ’Orstom, 13 rue Geoffroy l’Angevin, 75004 Paris, France 3Department of Geosciences, The University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, USA Absfract - Land mammal faunas of Paleocene age in the southern Andean basin of Bolivia and NW Argentina are calibrated by regional sequence stratigraphy and rnagnetostratigraphy. The local fauna from Tiupampa in Bolivia is -59.0 Ma, and is thus early Late Paleocene in age. Taxa from the lower part of the Lumbrera Formation in NW Argentina (long regarded as Early Eocene) are between -58.0-55.5 Ma, and thus Late Paleocene in age. A reassessment of the ages of local faunas from lhe Rfo Chico Formation in the San Jorge basin, Patagonia, southern Argentina, shows that lhe local fauna from the Banco Negro Infeiior is -60.0 Ma, mak- ing this the most ancient Cenozoic mammal fauna in South,America. Critical reevaluation the ltaboraí fauna and associated or All geology in SE Brazil favors lhe interpretation that it accumulated during a sea-level lowsland between -$8.2-56.5 Ma. known South American Paleocene land inammal faunas are thus between 60.0 and 55.5 Ma (i.e. Late Paleocene) and are here assigned to the Riochican Land Maminal Age, with four subages (from oldest to youngest: Peligrian, Tiupampian, Ilaboraian, Riochican S.S.). -

Diversity and Abundance of Roadkilled Bats in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest

diversity Article Diversity and Abundance of Roadkilled Bats in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest Lucas Damásio 1,2 , Laís Amorim Ferreira 3, Vinícius Teixeira Pimenta 3, Greiciane Gaburro Paneto 4, Alexandre Rosa dos Santos 5, Albert David Ditchfield 3,6, Helena Godoy Bergallo 7 and Aureo Banhos 1,3,* 1 Centro de Ciências Exatas, Naturais e da Saúde, Departamento de Biologia, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Alto Universitário, s/nº, Guararema, Alegre 29500-000, ES, Brazil; [email protected] 2 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Campus Darcy Ribeiro, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília 70910-900, DF, Brazil 3 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Biológicas (Biologia Animal), Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Av. Fernando Ferrari, 514, Prédio Bárbara Weinberg, Vitória 29075-910, ES, Brazil; [email protected] (L.A.F.); [email protected] (V.T.P.); [email protected] (A.D.D.) 4 Centro de Ciências Exatas, Naturais e da Saúde, Departamento de Farmácia e Nutrição, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Alto Universitário, s/nº, Guararema, Alegre 29500-000, ES, Brazil; [email protected] 5 Centro de Ciências Agrárias e Engenharias, Departamento de Engenharia Rural, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Alto Universitário, s/nº, Guararema, Alegre 29500-000, ES, Brazil; [email protected] 6 Centro de Ciências Humanas e Naturais, Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Av. Fernando Ferrari, 514, Vitória 29075-910, ES, Brazil 7 Departamento de Ecologia, Instituto de Biologia Roberto Alcântara Gomes, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rua São Francisco Xavier 524, Maracanã, Rio de Janeiro 20550-900, RJ, Brazil; [email protected] Citation: Damásio, L.; Ferreira, L.A.; * Correspondence: [email protected] Pimenta, V.T.; Paneto, G.G.; dos Santos, A.R.; Ditchfield, A.D.; Abstract: Faunal mortality from roadkill has a negative impact on global biodiversity, and bats are Bergallo, H.G.; Banhos, A. -

Redalyc.Mountain Vizcacha (Lagidium Cf. Peruanum) in Ecuador

Mastozoología Neotropical ISSN: 0327-9383 [email protected] Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Argentina Werner, Florian A.; Ledesma, Karim J.; Hidalgo B., Rodrigo Mountain vizcacha (Lagidium cf. peruanum) in Ecuador - First record of chinchillidae from the northern Andes Mastozoología Neotropical, vol. 13, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2006, pp. 271-274 Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Tucumán, Argentina Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45713213 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Mastozoología Neotropical, 13(2):271-274, Mendoza, 2006 ISSN 0327-9383 ©SAREM, 2006 Versión on-line ISSN 1666-0536 www.cricyt.edu.ar/mn.htm MOUNTAIN VIZCACHA (LAGIDIUM CF. PERUANUM) IN ECUADOR – FIRST RECORD OF CHINCHILLIDAE FROM THE NORTHERN ANDES Florian A. Werner¹, Karim J. Ledesma2, and Rodrigo Hidalgo B.3 1 Albrecht-von-Haller-Institute of Plant Sciences, University of Göttingen, Untere Karspüle 2, 37073 Göttingen, Germany; <[email protected]>. 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, U.S.A; <[email protected]>. 3 Colegio Nacional Eloy Alfaro, Gonzales Suarez y Sucre, Cariamanga, Ecuador; <[email protected]>. Key words. Biogeography. Caviomorpha. Distribution. Hystricomorpha. Viscacha. Chinchillidae is a family of hystricomorph Cerro Ahuaca is a granite inselberg 2 km rodents distributed in the Andes of Peru, from the town of Cariamanga (1950 m), Loja Bolivia, Chile and Argentina, and in lowland province (4°18’29.4’’ S, 79°32’47.2’’ W). -

The Beaver's Phylogenetic Lineage Illuminated by Retroposon Reads

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The Beaver’s Phylogenetic Lineage Illuminated by Retroposon Reads Liliya Doronina1,*, Andreas Matzke1,*, Gennady Churakov1,2, Monika Stoll3, Andreas Huge3 & Jürgen Schmitz1 Received: 13 October 2016 Solving problematic phylogenetic relationships often requires high quality genome data. However, Accepted: 25 January 2017 for many organisms such data are still not available. Among rodents, the phylogenetic position of the Published: 03 March 2017 beaver has always attracted special interest. The arrangement of the beaver’s masseter (jaw-closer) muscle once suggested a strong affinity to some sciurid rodents (e.g., squirrels), placing them in the Sciuromorpha suborder. Modern molecular data, however, suggested a closer relationship of beaver to the representatives of the mouse-related clade, but significant data from virtually homoplasy- free markers (for example retroposon insertions) for the exact position of the beaver have not been available. We derived a gross genome assembly from deposited genomic Illumina paired-end reads and extracted thousands of potential phylogenetically informative retroposon markers using the new bioinformatics coordinate extractor fastCOEX, enabling us to evaluate different hypotheses for the phylogenetic position of the beaver. Comparative results provided significant support for a clear relationship between beavers (Castoridae) and kangaroo rat-related species (Geomyoidea) (p < 0.0015, six markers, no conflicting data) within a significantly supported mouse-related clade (including Myodonta, Anomaluromorpha, and Castorimorpha) (p < 0.0015, six markers, no conflicting data). Most of an organism’s phylogenetic history is fossilized in their heritable genomic material. Using data from genome sequencing projects, particularly informative regions of this material can be extracted in sufficient num- bers to resolve the deepest history of speciation. -

Global Seagrass Distribution and Diversity: a Bioregional Model ⁎ F

Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 350 (2007) 3–20 www.elsevier.com/locate/jembe Global seagrass distribution and diversity: A bioregional model ⁎ F. Short a, , T. Carruthers b, W. Dennison b, M. Waycott c a Department of Natural Resources, University of New Hampshire, Jackson Estuarine Laboratory, Durham, NH 03824, USA b Integration and Application Network, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, Cambridge, MD 21613, USA c School of Marine and Tropical Biology, James Cook University, Townsville, 4811 Queensland, Australia Received 1 February 2007; received in revised form 31 May 2007; accepted 4 June 2007 Abstract Seagrasses, marine flowering plants, are widely distributed along temperate and tropical coastlines of the world. Seagrasses have key ecological roles in coastal ecosystems and can form extensive meadows supporting high biodiversity. The global species diversity of seagrasses is low (b60 species), but species can have ranges that extend for thousands of kilometers of coastline. Seagrass bioregions are defined here, based on species assemblages, species distributional ranges, and tropical and temperate influences. Six global bioregions are presented: four temperate and two tropical. The temperate bioregions include the Temperate North Atlantic, the Temperate North Pacific, the Mediterranean, and the Temperate Southern Oceans. The Temperate North Atlantic has low seagrass diversity, the major species being Zostera marina, typically occurring in estuaries and lagoons. The Temperate North Pacific has high seagrass diversity with Zostera spp. in estuaries and lagoons as well as Phyllospadix spp. in the surf zone. The Mediterranean region has clear water with vast meadows of moderate diversity of both temperate and tropical seagrasses, dominated by deep-growing Posidonia oceanica. -

Xenarthrans: 'Aliens'

Vet Times The website for the veterinary profession https://www.vettimes.co.uk XENARTHRANS: ‘ALIENS’ ON EARTH Author : JONATHAN CRACKNELL Categories : Vets Date : August 4, 2008 JONATHAN CRACKNELL finds that hanging around with sloths and their fellow Xenarthrans offers up exciting challenges XENARTHRANS: the name sounds like a race from a low-budget science fiction film. This is actually a super-order of mammals that get their name from their “alien” joint, which is exhibited in the vertebral joints. The Xenarthrans include 31 living species: six species of sloth, four anteaters and 21 species of armadillos – all of which originated in South America. Historically, these animals were classified within the order Edentata (meaning “without teeth”), which included pangolins and aardvarks. It was realised that this was a polyphyletic group, containing unrelated families. Therefore, the Xenarthra order was created. The Xenarthrans are a well-represented order in captivity, with banded armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus) becoming one of the new “exotic” exotics to be presented to clinicians. In zoological collections, giant anteaters (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), southern tamanduas (Tamandua tetradactyla), and sloths (typically the southern two-toed sloth – Choloepus didactylus – although others are present) are among the more common species housed in captivity. Every species has its own needs and oddities. With this brief review of each species, the author will look at basic anatomy and physiology, along with a quick review of some of the more commonly reported complaints for this group of animals. 1 / 14 Giant anteater The giant anteater’s most obvious feature is its long tongue and bushy tail. They are approximately 1.5 to two metres long and weigh in the region of 18kg to 45kg. -

Introduction Recent Classifications Regard the Order Pilosa, Anteaters

Introduction Recent classifications regard the order Pilosa, anteaters and sloths, and order Cingulata, the armadillos, within the superorder Xenarthra meaning “strange joints”. In the past, Pilosa and Cingulata wer regarded as suborders of the order Xenarthra, with the armadillos. Earlier still, both armadillos and pilosans were classified together with pangolins and the aardvark as the order Edentata meaning “toothless”. The orders Pilosa and Cingulata are distinguishable as the cingulatas have an armoured upper body and the pilosa have fur. Studies have concluded that sloths, anteaters, and armadillos diverged at least 75-80 million years ago and that they are as different from one another as are carnivores, bats and primates. The Pilosa are now considered almost exclusively a New World order, however, fossil records indicate that they were once found in Europe and possibly Asia. This order may have been distributed worldwide in the Cretaceous period, but became limited to South America and have remained there for most of their history and evolved into numerous groups. The Pilosa were once far more diverse than they are today; there are known to be 10 times as many fossil as living genera. The superorder is distinguished from all others by what are known as the xenarthrous vertebrae. There are secondary and sometimes even more, articulations between the vertebrae of the lumbar (lower back) series. In other words, consecutive vertebrae connect in more than one place. In addition, the pelvis connects with more of the spine than in other mammals. These adaptations to the spine give support, particularly to the hips. The name Xenarthra refers to this peculiarity of the spine and modem taxonomy places these three groups of animals together, even though they are very different from one another and they are highly specialized. -

GIANT ANTEATER PILOSA Family: Myrmecophagidae Genus: Myrmecophaga

GIANT ANTEATER PILOSA Family: Myrmecophagidae Genus: Myrmecophaga Species: tridactyla Range: Southern Mexico, Central America, South to Paraguay & Northern Argentina, & Trinidad Habitat: savanna, parkland, thorn Scrub, Steppe; montaine & tropical rainforest Niche: terrestrial, nocturnal, insectivorous Wild diet: ants, termites, and soft-bodied grubs Zoo diet: ant chow Life Span: (Wild) unknown (Captivity) 25 yrs 10 months recorded Sexual dimorphism: None Location in SF Zoo: Puente al Sur APPEARANCE & PHYSICAL ADAPTATIONS: Giant anteaters are quite distinctive, and are the largest of the anteaters. The snout is long (up to 45 cm in length) while the skull is streamlined with small eyes and ears. The tail is bushy and nearly as long as the body. These anteaters have thick coarse fur that is longer towards the tail (reaching up to 40 cm in length). Their coat is straw-like, brown with black and white stripes on the shoulders and a crest of hair along the middle of the back. Forelegs are white with black bands at the toes, while their hind feet have 5 short claws, and their forefeet have five claws with the inner three being very long and sharp. They shuffle while walking and move slowly but are capable of running quickly if necessary. Their weight is born on the Weight: 39.6 to 85.8 lbs knuckles and wrist to protect the claws. These front limbs provide HRL: 3.28 to 3.94 ft TL: 3.5 ft some defense against its natural predators, the puma and the jaguar. Giant anteaters have long, tubular snouts, well adapted for working its way into the anthills and termite nests it rips open with its large front claws. -

Paucituberculata: Caenolestes) from the Huancabamba Region of East Andean Peru

Mammal Study 28: 145–148 (2003) © the Mammalogical Society of Japan Short communication Shrew opossums (Paucituberculata: Caenolestes) from the Huancabamba region of east Andean Peru Darrin P. Lunde1,* and Victor Pacheco2 1 Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy), American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West @ 79th Street, New York, NY 10024, USA 2 Curador de Mamíferos, Museo de Historia Natural, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Apartado 14-0434, Lima, Peru Shrew opossums of the genus Caenolestes are restricted Peru north and south of the Huancabamba Depression. to the northern Andes and include four species: C. fuligi- nosus, C. convelatus, C. caniventer and C. condorensis Materials and methods (Albuja and Patterson 1996). Caenolestes fuliginosus is a highland species of the páramos of central Ecuador, Small mammal surveys were conducted in the Depar- Colombia and western Venezuela, but the remaining tamento de Cajamarca, Peru in June 1995 and June 1996. three species occur in sub-tropical montane forests at Victor and Museum Special snaptraps and Sherman live lower elevations (Albuja and Patterson 1996). Caeno- traps were baited with a 6 : 2 : 2 : 1 mixture of peanut lestes convelatus and C. caniventer are known from the butter, oatmeal, raisins and bacon. Specimens were western slopes of the Andes, the former from Colombia preserved as either dried study skins and skulls with and northern Ecuador and the latter from southern alcohol preserved carcasses, or as whole specimens that Ecuador and northern Peru (Bublitz 1987), while the were first fixed in formalin and subsequently transferred recently described Caenolestes condorensis is currently to 70% ethanol. -

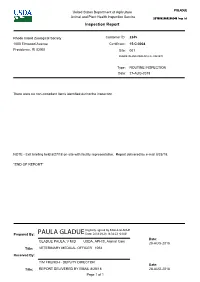

Inspection Report

PGLADUE United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service 2016082569255248 Insp_id Inspection Report Rhode Island Zoological Society Customer ID: 2245 1000 Elmwood Avenue Certificate: 15-C-0004 Providence, RI 02907 Site: 001 RHODE ISLAND ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY Type: ROUTINE INSPECTION Date: 27-AUG-2018 There were no non-compliant items identified during the inspection. NOTE - Exit briefing held 8/27/18 on-site with facility representative. Report delivered by e-mail 8/28/18. *END OF REPORT* Prepared By: Date: GLADUE PAULA, V M D USDA, APHIS, Animal Care 28-AUG-2018 Title: VETERINARY MEDICAL OFFICER 1054 Received By: TIM FRENCH - DEPUTY DIRECTOR Date: Title: REPORT DELIVERED BY EMAIL 8/28/18 28-AUG-2018 Page 1 of 1 United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 2245 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 27-AUG-18 Species Inspected Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 2245 15-C-0004 001 RHODE ISLAND ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY 27-AUG-18 Count Scientific Name Common Name 000004 Acinonyx jubatus CHEETAH 000002 Ailurus fulgens RED PANDA 000002 Alouatta caraya BLACK HOWLER 000003 Ammotragus lervia BARBARY SHEEP 000004 Antilocapra americana PRONGHORN 000002 Arctictis binturong BINTURONG 000003 Artibeus jamaicensis JAMAICAN FRUIT-EATING BAT / JAMAICAN FRUIT BAT 000004 Atelerix albiventris FOUR-TOED HEDGEHOG (MOST COMMON PET HEDGEHOG) 000001 Babyrousa babyrussa BABIRUSA 000003 Bison bison AMERICAN BISON 000002 Bos taurus CATTLE / COW / OX / WATUSI 000001 Budorcas taxicolor TAKIN 000003 Callicebus