Cat-Scratch Disease STEPHEN A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

If Needed You Can Use Two Lines

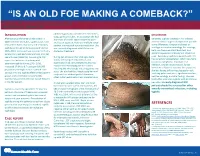

“IS AN OLD FOE MAKING A COMEBACK?” •Eyob Tadesse MD1; Samie Meskele MD1; Ankoor Biswas MD1 •Aurora Health Care, Milwaukee WI. NTRODUCTION abdomen gradually spread to her extremities, DISCUSSION I scalp, palms and soles. In association she had After being on the verge of elimination in shortness of breath, vague abdominal pain Generally, syphilis presents in HIV infected 2000 in the United States, syphilis cases have and loss of appetite, history of multiple sexual patients similar to general population yet with rebounded. Rates of primary and secondary partner, unprotected sex and prostitution. She some differences. Diagnosis is based on syphilis continued to increase overall during was recently diagnosed with HIV but not serologic test and microbiology. For serology, 2005–2013. Increases have occurred primarily started on treatment. both non treponemal antibody test, and among men, and particularly among men has specific treponemal antibody test should be used. Secondary syphilis in patients with HIV sex with men (MSM)(1). According to CDC During her admission her vital signs were has varied skin presentation, which can mimic report the incidence of primary and stable, she had pale conjunctivae, skin cutaneous lymphoma, mycobacterial secondary syphilis during 2015–2016, examination had demonstrated widespread macular and maculopapular skin lesions infection, bacillary angiomatosis, fungal increased 17.6% to 8.7 cases per 100,000 infections or Kaposi’s sarcoma. In our patient, population, the highest rate reported since involving the whole body including palms and soles. She also had thin, fragile scalp hair and she was having diffuse maculopapular rash, 1993(2). HIV and syphilis affect similar patient scalp hair loss without genital ulceration; involving palms and soles, significant hair loss, groups and co-infection is common(3). -

A Fatal Case of Necrotising Fasciitis of the Eyelid

Br J Ophthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.72.6.428 on 1 June 1988. Downloaded from British Journal of Ophthalmology, 1988, 72, 428-431 A fatal case of necrotising fasciitis of the eyelid R WALTERS From Southampton Eye Hospital, Wilton A venue, Southampton S09 4XW SUMMARY A fatal case of necrotising fasciitis in a 35-year-old man is described and the differential diagnosis and management discussed. Necrotising fasciitis is a potentially fatal skin were taken. The Gram stain revealed Gram-positive infection which is being increasingly recognised as an cocci. He was then treated with intravenous underdiagnosed condition. It requires prompt diag- cefotaxime and gentamicin and topical chlor- nosis, investigation, and treatment. Early surgical amphenicol and gentamicin drops. Because of the debridement is, in combination with suitable intra- poor visual acuity of the right eye it was thought that venous antibiotics, the mainstay of treatment. an orbital cellulitis could not be excluded despite the normal eye movements and absence of proptosis. He Case report was therefore transferred to the General Hospital under the care of an ear, nose, and throat consultant In December 1985 a previously fit 35-year-old factory in order to exclude underlying sinus disease and an manager was referred by his general practitioner to associated abscess. the Casualty Department of the Southampton Eye Skull x-rays (including sinus views) revealed no Hospital with a 12-hour history of increasing redness abnormality and he was therefore continued on his and swelling of his right upper lid. He said that two medical treatment (with the addition of intravenous http://bjo.bmj.com/ days previously he had been poked in the same eye by metronidazole), the presumed diagnosis being his daughter (who had been playing with her guinea- preseptal cellulitis. -

HIV and the SKIN • Sudden Acute Exacerbations • Treatment Failure DR

2018/08/13 KEY FEATURES • Atypical presentation of common disorders • Severe or exaggerated presentations HIV AND THE SKIN • Sudden acute exacerbations • Treatment failure DR. FREDAH MALEKA DERMATOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA:KALAFONG VIRAL INFECTIONS EXANTHEM OF PRIMARY HIV INFECTION • Exanthem of primary HIV infection • Acute retroviral syndrome • Herpes simplex virus (HSV) • Morbilliform rash (exanthem) : 2-4 weeks after HIV exposure • Varicella Zoster virus (VZV) • Typically generalised • Molluscum contagiosum (Poxvirus) • Pronounced on face and trunk, sparing distal extremities • Human papillomavirus (HPV) • Associated : fever, lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis • Epstein Barr virus (EBV) • DDX: drug reaction • Cytomegalovirus (CMV) • other viral infections – EBV, Enteroviruses, Hepatitis B virus 1 2018/08/13 HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS(HSV) • Vesicular eruption due to HSV 1&2 • Primary lesion: painful, grouped vesicles on an erythematous base • HIV: attacks are more frequent and severe • : chronic, non-healing, deep ulcers, with scarring and tissue destruction • CLUE: severe pain and recurrences • DDX: syphilis, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum • Tzanck smear, Histology, Viral culture HSV • Treatment: Acyclovir 400mg tds 7-10 days • Alternatives: Valacyclovir and Famciclovir • In setting of treatment failure, viral isolates tested for resistance against acyclovir • Alternative drugs: Foscarnet, Cidofovir • Chronic suppressive therapy ( >8 attacks per year) 2 2018/08/13 VARICELLA • Chickenpox • Presents with erythematous papules and umbilicated -

WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/05 (2006.01) A61P 31/02 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/CA20 14/000 174 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 4 March 2014 (04.03.2014) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (25) Filing Language: English OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (26) Publication Language: English SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, (30) Priority Data: ZW. 13/790,91 1 8 March 2013 (08.03.2013) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant: LABORATOIRE M2 [CA/CA]; 4005-A, rue kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, de la Garlock, Sherbrooke, Quebec J1L 1W9 (CA). GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, (72) Inventors: LEMIRE, Gaetan; 6505, rue de la fougere, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, Sherbrooke, Quebec JIN 3W3 (CA). -

Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis Are Tick-Borne Diseases Caused by Obligate Anaplasmosis: Intracellular Bacteria in the Genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma

Ehrlichiosis and Importance Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are tick-borne diseases caused by obligate Anaplasmosis: intracellular bacteria in the genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma. These organisms are widespread in nature; the reservoir hosts include numerous wild animals, as well as Zoonotic Species some domesticated species. For many years, Ehrlichia and Anaplasma species have been known to cause illness in pets and livestock. The consequences of exposure vary Canine Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, from asymptomatic infections to severe, potentially fatal illness. Some organisms Canine Hemorrhagic Fever, have also been recognized as human pathogens since the 1980s and 1990s. Tropical Canine Pancytopenia, Etiology Tracker Dog Disease, Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are caused by members of the genera Ehrlichia Canine Tick Typhus, and Anaplasma, respectively. Both genera contain small, pleomorphic, Gram negative, Nairobi Bleeding Disorder, obligate intracellular organisms, and belong to the family Anaplasmataceae, order Canine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, Rickettsiales. They are classified as α-proteobacteria. A number of Ehrlichia and Canine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Anaplasma species affect animals. A limited number of these organisms have also Equine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, been identified in people. Equine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Recent changes in taxonomy can make the nomenclature of the Anaplasmataceae Tick-borne Fever, and their diseases somewhat confusing. At one time, ehrlichiosis was a group of Pasture Fever, diseases caused by organisms that mostly replicated in membrane-bound cytoplasmic Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, vacuoles of leukocytes, and belonged to the genus Ehrlichia, tribe Ehrlichieae and Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, family Rickettsiaceae. The names of the diseases were often based on the host Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, species, together with type of leukocyte most often infected. -

Rheumatic Manifestations of Bartonella Infection in 2 Children MOHAMMAD J

Case Report Rheumatic Manifestations of Bartonella Infection in 2 Children MOHAMMAD J. AL-MATAR, ROSS E. PETTY, DAVID A. CABRAL, LORI B. TUCKER, BANAFSHI PEYVANDI, JULIE PRENDIVILLE, JACK FORBES, ROBYN CAIRNS, and RALPH ROTHSTEIN ABSTRACT. We describe 2 patients with very unusual rheumatological presentations presumably caused by Bartonella infection: one had myositis of proximal thigh muscles bilaterally, and the other had arthritis and skin nodules. Both patients had very high levels of antibody to Bartonella that decreased in asso- ciation with clinical improvement. Bartonella infection should be considered in the differential diag- nosis of unusual myositis or arthritis in children. (J Rheumatol 2002;29:184–6) Key Indexing Terms: MYOSITIS ARTHRITIS BARTONELLA Infection with Bartonella species has a wide range of mani- was slightly increased at 9.86 IU/l (normal 4.51–9.16), and IgA was 2.1 IU/l festations in children including cat scratch disease (regional (normal 0.2–1.0). C3 was 0.11 g/l (normal 0.77–1.43) and C4 was 0.28 (nor- mal 0.07–0.40). Antinuclear antibodies were present at a titer of 1:40, the anti- granulomatous lymphadenitis), bacillary angiomatosis, streptolysin O titer was 35 (normal < 200), and the anti-DNAase B titer was encephalitis, Parinaud’s oculoglandular syndrome, Trench 1:85 (normal). Urinalysis showed 50–100 erythrocytes and 5–10 leukocytes fever (Vincent’s angina), osteomyelitis, granulomatous per high power field. Routine cultures of urine, blood, and throat were nega- hepatitis, splenitis, pneumonitis, endocarditis, and fever of tive. Liver enzymes, electrolytes, HIV serology, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, unknown origin1-3. -

An Important One Health Opportunity

veterinary sciences Review Ehrlichioses: An Important One Health Opportunity Tais B. Saito * and David H. Walker Department of Pathology, University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Galveston, TX 77555, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-1409-772-4813 Academic Editor: Ulrike Munderloh Received: 15 July 2016; Accepted: 25 August 2016; Published: 31 August 2016 Abstract: Ehrlichioses are caused by obligately intracellular bacteria that are maintained subclinically in a persistently infected vertebrate host and a tick vector. The most severe life-threatening illnesses, such as human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis and heartwater, occur in incidental hosts. Ehrlichia have a developmental cycle involving an infectious, nonreplicating, dense core cell and a noninfectious, replicating reticulate cell. Ehrlichiae secrete proteins that bind to host cytoplasmic proteins and nuclear chromatin, manipulating the host cell environment to their advantage. Severe disease in immunocompetent hosts is mediated in large part by immunologic and inflammatory mechanisms, including overproduction of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), which is produced by CD8 T lymphocytes, and interleukin-10 (IL-10). Immune components that contribute to control of ehrlichial infection include CD4 and CD8 T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), IL-12, and antibodies. Some immune components, such as TNF-α, perforin, and CD8 T cells, play both pathogenic and protective roles. In contrast with the immunocompetent host, which may die with few detectable organisms owing to the overly strong immune response, immunodeficient hosts die with overwhelming infection and large quantities of organisms in the tissues. Vaccine development is challenging because of antigenic diversity of E. -

Spider Bite Inducing Superficial Lymphangitis: a Case Report

ISSN: 2574-1241 Volume 5- Issue 4: 2018 DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.12.002232 El Anzi Ouiam. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res Case Report Open Access Spider Bite Inducing Superficial Lymphangitis: A Case Report El Anzi Ouiam*, Meziane Mariam and Hassam Badredine Department of Dermatology-Venereology, Morocco Received: Published: *Corresponding: December author: 04, 2018; : December 17, 2018 El Anzi Ouiam, Department of Dermatology-Venereology, Morocco Abstract Superficial lymphangitis after insect bite is the result of an allergic reaction to the insect antigen. We present the case of a 22-year-old patient with no notable medical history, presented with a pruritic rash on the chest, two days after an insect bite. Unlike bacterial lymphangitis, the site of insectKeywords: bite is not painful but pruritic. Spider Bite; Lymphangitis; Allergic Reaction Introduction lymphadenopathy. Different authors assume that superficial Superficial lymphangitis after insect bite is the result of an lymphangitis after spider sting is the consequence of an allergic allergic reaction to the insect antigen, which is injected into the skin immune reaction due to insect toxins [3]. Unlike bacterial andClinical drained Case by lymphatic vessels [1]. lymphangitis, the site of insect bite is not painful but pruritic. It’s also characterised by the absence of fever and lymph node A 22-year-old female with no notable medical history, presented enlargement and a rapid spontaneous regression [1-3] (Figure 1). with a pruritic rash on the chest. She mentioned intense pruritus and low pain. Two days before she had been bitten on the shoulder by a spider. Physical examination showed a red linear lesion starting from erythematous macule of the shoulder and extending toward the anterior wall of the chest. -

Tick-Borne Diseases in Maine a Physician’S Reference Manual Deer Tick Dog Tick Lonestar Tick (CDC Photo)

tick-borne diseases in Maine A Physician’s Reference Manual Deer Tick Dog Tick Lonestar Tick (CDC PHOTO) Nymph Nymph Nymph Adult Male Adult Male Adult Male Adult Female Adult Female Adult Female images not to scale know your ticks Ticks are generally found in brushy or wooded areas, near the DEER TICK DOG TICK LONESTAR TICK Ixodes scapularis Dermacentor variabilis Amblyomma americanum ground; they cannot jump or fly. Ticks are attracted to a variety (also called blacklegged tick) (also called wood tick) of host factors including body heat and carbon dioxide. They will Diseases Diseases Diseases transfer to a potential host when one brushes directly against Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted Ehrlichiosis anaplasmosis, babesiosis fever and tularemia them and then seek a site for attachment. What bites What bites What bites Nymph and adult females Nymph and adult females Adult females When When When April through September in Anytime temperatures are April through August New England, year-round in above freezing, greatest Southern U.S. Coloring risk is spring through fall Adult females have a dark Coloring Coloring brown body with whitish Adult females have a brown Adult females have a markings on its hood body with a white spot on reddish-brown tear shaped the hood Size: body with dark brown hood Unfed Adults: Size: Size: Watermelon seed Nymphs: Poppy seed Nymphs: Poppy seed Unfed Adults: Sesame seed Unfed Adults: Sesame seed suMMer fever algorithM ALGORITHM FOR DIFFERENTIATING TICK-BORNE DISEASES IN MAINE Patient resides, works, or recreates in an area likely to have ticks and is exhibiting fever, This algorithm is intended for use as a general guide when pursuing a diagnosis. -

Leptospirosis: a Waterborne Zoonotic Disease of Global Importance

August 2006 volume 22 number 08 Leptospirosis: A waterborne zoonotic disease of global importance INTRODUCTION syndrome has two phases: a septicemic and an immune phase (Levett, 2005). Leptospirosis is considered one of the most common zoonotic diseases It is in the immune phase that organ-specific damage and more severe illness globally. In the United States, outbreaks are increasingly being reported is seen. See text box for more information on the two phases. The typical among those participating in recreational water activities (Centers for Disease presenting signs of leptospirosis in humans are fever, headache, chills, con- Control and Prevention [CDC], 1996, 1998, and 2001) and sporadic cases are junctival suffusion, and myalgia (particularly in calf and lumbar areas) often underdiagnosed. With the onset of warm temperatures, increased (Heymann, 2004). Less common signs include a biphasic fever, meningitis, outdoor activities, and travel, Georgia may expect to see more leptospirosis photosensitivity, rash, and hepatic or renal failure. cases. DIAGNOSIS OF LEPTOSPIROSIS Leptospirosis is a zoonosis caused by infection with the bacterium Leptospira Detecting serum antibodies against leptospira interrogans. The disease occurs worldwide, but it is most common in temper- • Microscopic Agglutination Titers (MAT) ate regions in the late summer and early fall and in tropical regions during o Paired serum samples which show a four-fold rise in rainy seasons. It is not surprising that Hawaii has the highest incidence of titer confirm the diagnosis; a single high titer in a per- leptospirosis in the United States (Levett, 2005). The reservoir of pathogenic son clinically suspected to have leptospirosis is highly leptospires is the renal tubules of wild and domestic animals. -

Erysipelas Following a Fracture: About a Case

Journal of Dermatology & Cosmetology Case Report Open Access Erysipelas following a fracture: about a case Abstract Volume 3 Issue 1 - 2019 Erysipelas on postoperative scar is a rare entity. In orthopedic traumatology, Abdelhafid El Marfi,1 Mohamed El Idrissi,1 El we have only the 3cases reported in the work of Dhrif occurred during prosthetic Ibrahimi Abdelhalim,1 Abdelmajid El Mrini,1 implantation. We present through this article, the case of postoperative erysipelas on 2 2 an osteosynthesis scar of a fracture of the lower quarter of the leg in a 58-year-old Kaoutar Laamari, Fatima Zahra Mernissi 1 woman. Department of Traumatology Orthopedy B4, University Hospital Hassan II Fez, Morocco 2Department of Dermatology, University Hospital Hassan II Fez, Morocco Correspondence: Abdelhafid El Marfi, Department of Traumatology Orthopedy B4, University Hospital Hassan II Fez, Morocco, Tel 0021 2678 3398 79, Email Received: January 04, 2018 | Published: January 28, 2019 Introduction Erysipelas is an infectious disease of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue commonly caused by streptococci.1 It is a clinical form of acute cellulitis.2 Clinically, it is characterized by the acute onset of local signs of inflammation such as erythema, oedema, pain and heat. In its classic form, it is accompanied by systemic signs such as fever, chills and malaise and sometimes nausea and vomiting.3,4 Erysipelas can be serious but rarely fatal. It has a rapid and favorable response to antibacterial therapy.5,6 From an epidemiological point of view, we consider the existence of a portal of entry, lymphoedema and obesity as the main risk factors for occurrence. -

Overview of Fever of Unknown Origin in Adult and Paediatric Patients L

Overview of fever of unknown origin in adult and paediatric patients L. Attard1, M. Tadolini1, D.U. De Rose2, M. Cattalini2 1Infectious Diseases Unit, Department ABSTRACT been proposed, including removing the of Medical and Surgical Sciences, Alma Fever of unknown origin (FUO) can requirement for in-hospital evaluation Mater Studiorum University of Bologna; be caused by a wide group of dis- due to an increased sophistication of 2Paediatric Clinic, University of Brescia eases, and can include both benign outpatient evaluation. Expansion of the and ASST Spedali Civili di Brescia, Italy. and serious conditions. Since the first definition has also been suggested to Luciano Attard, MD definition of FUO in the early 1960s, include sub-categories of FUO. In par- Marina Tadolini, MD Domenico Umberto De Rose, MD several updates to the definition, di- ticular, in 1991 Durak and Street re-de- Marco Cattalini, MD agnostic and therapeutic approaches fined FUO into four categories: classic Please address correspondence to: have been proposed. This review out- FUO; nosocomial FUO; neutropenic Marina Tadolini, MD, lines a case report of an elderly Ital- FUO; and human immunodeficiency Via Massarenti 11, ian male patient with high fever and virus (HIV)-associated FUO, and pro- 40138 Bologna, Italy. migrating arthralgia who underwent posed three outpatient visits and re- E-mail: [email protected] many procedures and treatments before lated investigations as an alternative to Received on November 27, 2017, accepted a final diagnosis of Adult-onset Still’s “1 week of hospitalisation” (5). on December, 7, 2017. disease was achieved. This case report In 1997, Arnow and Flaherty updated Clin Exp Rheumatol 2018; 36 (Suppl.