What Sufjan Stevens' Post-Literal and Post-Rational Aesthetic Communicates About the D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sufjan Stevens Yarn/Wire

BAM 2015 Winter/Spring Season #Sufjan Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer Round-Up Sufjan Stevens Yarn/Wire BAM Harvey Theater Jan 20—25 at 7:30pm Running time: one hour and 15 minutes, no intermission Season Sponsor: Viacom is the BAM 2015 Music Sponsor The Steinberg Screen at the BAM Harvey Theater is made possible by The Joseph S. and Diane H. Steinberg Charitable Trust Major support for Round-Up provided by The Frederick Loewe Foundation Major support for music at BAM provided by: Frances Bermanzohn & Alan Roseman Pablo J. Salame Round-Up FILM Director, Composer Sufjan Stevens Cinematographer Aaron Craig Cinematographer Alex Craig Co-Producer Lisa Moran Co-Producer We Are Films COMPANY Sound Mix Dan Bora Lighting Seth Reiser Stage Manager Mary-Sue Gregson Production Management Lisa Moran Live Projection & Design Josh Higgason Round-Up was filmed at the Pendleton Round-Up in eastern Oregon, September, 2013. Additional footage was shot in Brooklyn and upstate New York, July 2014. Courtesy We Are Films Courtesy We Are Films Who’s Who SUFJAN STEVENS was born in Detroit and WE ARE FILMS raised in northern Michigan. He attended Hope Alex and Aaron Craig discovered their passion for College in Holland, MI, and the masters program filmmaking in their early teens. With camcord- for writers at the New School for Social Research ers in hand, willing neighbors as actors, and the in New York City. -

J. Tillman Release Date: 09/22/2009 CD UPC Year in the Kingdom 6 56605 46022 2

a WESTERN VINYL release WV068 || Format: CD J. Tillman Release Date: 09/22/2009 CD UPC Year In The Kingdom 6 56605 46022 2 WESTERN VINYL WWW.WESTERNVINYL.COM [email protected] SELLING POINTS - Josh will embark on his first US tour in years in November. In September he’ll tour the EU - Josh has released several critically acclaimed records and has toured in Europe and throughout 1. Year In The kingdom the US. 2. Crosswinds 3. Earthly Bodies - Features artwork by acclaimed designer and 4. Howling Light illustrator Mario Hugo 5. Though I Have Wronged You 6. Age Of Man PRESS QUOTES 7. There Is No Good In me “This is no mere side-project. His first proper UK release is a treat, at times conjuring the beautiful, stark bleakness of Nick Drake, 8. Marked In The Valley elsewhere not afraid to crank things up, as on the distortion heavy 9. Light Of The Living ‘New Imperial Grand Blues’. Best of all is the upliftingly redemptive ‘Above All Men’.” – Q Magazine “An existentialist’s songs cycle, Vacilando…’s lonely songs reinforce each other with an impeccable internal logic, fashioning its own little world-weary universe, wherein less is more, simple guitar strums signal seismic shifts in mood, shadows bump into one Year In The Kingdom unravels some kind of galactic wilderness. Tillman's 6th another. Like Neil Young’s On the Beach or Jason Molina’s Songs:Ohia incarnation, it’s best heard late at night, alone, lights album lyrically borders on mystic; proffering a transcendent union, an down low, one last glass of wine in the wings.” – Uncut effortlessness. -

The Carroll News

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 10-28-2010 The aC rroll News- Vol. 87, No. 7 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News- Vol. 87, No. 7" (2010). The Carroll News. 823. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/823 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JCU students bring “I Hate Hamlet” to life on the stage, p. 7 THE Thursday,C OctoberARROLL 28, 2010 Serving John Carroll University Since N1925 EWSVol. 87, No. 7 Students Revamping recycling The University hopes to increase recycling on campus and Speak get students more involved cans. Students can’t say [once the first to receive both the recycling bins Emily Gaffney for the entire floor and for each student Campus Editor bins are in place] they look the same anymore,” said Hill. room to test the new program. This could be implemented as soon as the John Carroll University is working Educational posters will also be end of the week. to make recycling bins more distin- posted inside the trash rooms. The rest of the student floors will guishable and increase recycling on Additionally, small blue recycling receive both sets of recycling bins over “I think it campus. bins will be distributed to each stu- Christmas Break. -

Call Me Queer

Call Me Queer: Queer theory and the Soundtrack of Call Me by Your Name Zora van Harten 4246551 dr. Floris Schuiling bachelor thesis MU3V14004 Musicology University of Utrecht Word count: 5559 Introduction In a culture that classifies the world through binary categories, entities that fall in between those 1 categories are often subjected to fear and anxiety. It is therefore no surprise that two subjects as fluid, undefinable and abstract as music and queer identities both have been occupying 2 controversial positions within Western history. Remarkably, both these subjects are central to the critically acclaimed film Call Me by Your Name. The film, directed by Italian director Luca Guadagnino, is part of his so-called “desire” film trilogy, together with earlier films Il Sono L’Amore (2009) and A Bigger Splash (2015). It tells the story of a summer romance between a seventeen year old boy called Elio, and Oliver, a twenty-eight year old scholar who is invited to work on his doctoral thesis while staying in Elio’s parents’ summer house in Italy. Its narrative features a nuanced and fluid, and therefore queer conception of desire and sexuality; the characters stay out of defined categories through the ambiguous meaning of the film’s dialogue and their sexual identities. In this film, music takes on a remarkable position. Elio uses music to express the multiple outlets regarding his desire for Oliver. Moreover, the songs, and piano works of the soundtrack are often combined with the relatively loud presence of sounds such as the movement of water, crickets or the wind rushing through the trees which could point towards a more affective experience of sound for the audience. -

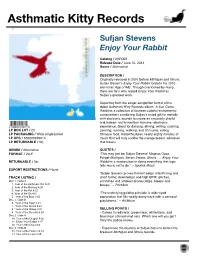

Asthmatic Kitty Records ! ! Sufjan Stevens Enjoy Your Rabbit

Asthmatic Kitty Records ! ! Sufjan Stevens Enjoy Your Rabbit Catalog / AKR003 Release Date / June 10, 2014 Genre / Alternative DESCRIPTION / Originally released in 2001 before Michigan and Illinois, Sufjan Steven’s Enjoy Your Rabbit foretells his 2010 electronic Age of Adz. Though overlooked by many, there are fans who regard Enjoy Your Rabbit as Sufjan’s greatest work. Departing from the singer-songwriter format of his debut Asthmatic Kitty Records album, A Sun Came, Rabbit is a collection of fourteen colorful instrumental compositions combining Sufjan’s noted gift for melody ! with electronic sounds to create an unusually playful and human- not to mention humane- electronic experience. Great for dancing, driving, writing, cooking, LP BOX LOT / 25 painting, running, walking, and of course, eating LP PACKAGING / Wide single jacket Chinese food, Rabbit features nearly eighty minutes of LP UPC / 656605919614 music that will truly soothe the savage breast, whatever LP RETURNABLE / No that means. GENRE / Alternative QUOTES / FORMAT / 2xLP “This may just be Sufjan Stevens' Magnus Opus. Forget Michigan, Seven Swans, Illinois . Enjoy Your RETURNABLE / No Rabbit is a masterclass in doing everything that logic tells music not to do.” – Sputnik Music EXPORT RESTRICTIONS / None “Sufjan Stevens proves himself adept of both long and TRACK LISTING / short forms; downtempo and high BPM; glitches, Disc 1 / Side A scratches and ambient drones; blips, bleeps and 1. Year of the Asthmatic Cat 0:24 bloops.” – Pitchfork 2. Year of the Monkey 4:20 3. Year of the Rat 8:22 4. Year of the Ox 4:01 “The underlying guiding principle is wide-eyed 5. -

Crystal Ship 3

EDITORIAL ADDRESS: JOHN D. OWEN, 22,CONISTON WAY, BLETCHLEY, MILTON KEYNES ENGLAND MK2 5EA GILDED SPLINTERS : The generation gap in Rock. p. 4 STAR SAILORS: Philip K.Dick can build you. by Andy Muir p. 6 FEAR & LOATHING IN MIDDLE-EARTH. The Silmarillion gets the finger from Joseph Nicholas p. 9 CADENCE & CASCADE : RyCooder p.14 THE QUALITY OF MERSEY : A personal account of a Scouse New Year by Patrick Holligan p.16 ISLANDS IN THE SKY : Can SF really come true so soon? p.19 JUST A PINCH OF....: Some thoughts on spells, charms and toads , by Peter Presford p.25 ARTIST CREDITS : Yes folks, real artists! p.25 RIPPLES : Being an actual real live letter column. p.26 RECENT REEDS : The return of the book reviews. p.50 In both size and content this issue of the Crystal Ship has reached a new high: so has the printers' bill! So, finally, I've come to the stage where one of two things must happen. Either I cut back to a very small circulation and keep paying for it all myself, or I accept subscriptions for the 'zine. Until now, I haven't particularly thought the 'zine worth it,( typically modest self-depreciation!), but cir cumstances (approaching bankruptcy) force me to accept the second alter native. So from now on readers who either don't contribute, exchange or send letters of comment (even if its only "I like/loathe it") will have to pay real money, at a rate of 25p a copy in Britain or 2 per dollar over seas (bills only please). -

The Echo: September 23, 2005

Taylor University Pillars at Taylor University 2005-2006 (Volume 93) The Echo 9-23-2005 The Echo: September 23, 2005 Taylor University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/echo-2005-2006 Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Taylor University, "The Echo: September 23, 2005" (2005). 2005-2006 (Volume 93). 5. https://pillars.taylor.edu/echo-2005-2006/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The Echo at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2005-2006 (Volume 93) by an authorized administrator of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Projectors Taylor gets go MIA facelift THEECHO Officials look TU welcomes into theft 'real' facebook SEPTEMBER 23, 2005 T AYLOR UNIVERSITY SINCE 1915 - VOLUME 93, NO. 5 ROJAM prepares Prayer renews hearts pre-majors BY CHRISTIANNA LUY "I had read these prayers NEWS EDITOR BY MEGAN BAIRD before, but never picked CONTRIBUTER Spiritual Renewal Week is them apart as Dr. Farmer more than a tradition at Tay- did," sophomore Bree Tsuleff Taylor’s freshman class has lor. At the beginning of ev- said. 75 undeclared or pre-majors. ery semester students come Farmer outlined Jesus' Although freshmen are not together, lift their voices and prayers. He prays for his required to immediately de- deepen their knowledge of people's protection, undeni- clare a major, the high num- God’s Word. able unity and knowledge of ber of pre-majors prompted “The intent is to set the Christs joy. -

Haunted House Scares up Funds His Wife Debra R

Vol. 88 Issue 35 November 2, 2010 Sufjan Stevens Opens WHAT’S INSIDE musical floodgates OPINION Sex and violence in video New album Age of Adz blends acoustic games goes to vote and electronic sounds ........................................4 See ALBUM, page 5 DETOUR Shiny Toy Guns and Seven Year War Halloween bash Free or discounted ........................................6 food for student voters SPORTS To entice student voters local eateries will be Bee in the Know: offering specials to voters Postseason expansion See COMMUNITY, page 3 ........................................8 dailytitan.com The Student Voice of California State University, Fullerton Memorial ONLINE www.dailytitan.comEXCLUSIVES for SoCal Multimedia artist Life of CSUF alumni artist Patrick Merrill is remembered HEATHER REST Daily Titan Innovative Community members, educators, family and friends gathered Satur- Vending Machine day afternoon to celebrate the life See what’s Scan to view of Southern California artist and re- for sale at the nowned print-maker Patrick Merrill. new vending The day consisted of a memorial machine at service, an artist panel discussion and dailytitan.com/ an exhibition opening at Begovich shop24 Gallery; Patrick Merrill: revelation, which will run through Nov. 9. “He’s got a really diverse back- ground as an artist and as an educa- tor. So we have a lot of people from all over here today,” said Dana Lamb, Shekell Visual Arts Department chair. “His prime medium was print making. pleads guilty The work is based strongly on his social and political perspective and State-of-the-art convenience store installed observations in his life; he had a very to charges interesting life.” Daily Titan JOHNNY LE / Merrill died Aug. -

Iceland Airwaves: the Final Countdown B14 #1 and at All Major Tourist Attractions and Tourist Information Centres

Airwaves Special Mínus + Mr. Silla & Mongoose + Bloodgroup + Ben Frost + Þórir The Lonesome Traveller is Out and About • Going Vegan in Svið-land • Ragnar Kjartansson Finds God Awakening the Couch Potatoes • Icelanders and their Elves • Sequences Art Festival + info. A Complete City Guide and Listings: Map, Dining, Music, Arts and Events Issue 16 // Oct 5 - Nov 1 2007 2557 CIN Grapevine jona 330 MBL.ai 10/3/07 12:07:01 PM 02 | Reykjavík Grapevine | Issue 16 2007 | Year 5 | October 05 – November 01 The Reykjavík Grapevine Articles Vesturgata 5, 101 Reykjavík www.grapevine.is Elves in Cultural Vocabulary 06 [email protected] Interview with professor Terry Gunnel www.myspace.com/reykjavikgrapevine Published by Fröken ehf. I am Going For a Cup of Coffee 08 Opinion by Viktor Banke Editorial: +354 540 3600 / [email protected] The Grapevine Guide to the Airwaves Personalities 08 Advertising: Opinion by Sveinn Birkir Björnsson +354 540 3605 / [email protected] Publisher: Vegan Iceland? 10 +354 540 3601 / [email protected] The Difficulties of Being a Vegan in Iceland The Reykjavík Grapevine Staff Can We Do This Indefinately? 12 Publisher: Interview with designer Olof Kolte Hilmar Steinn Grétarsson [email protected] Airwaves Special 14 Editor: Interviews with Ben Frost, Bloodgroup, Þórir and Mr. Silla & Mongoose Sveinn Birkir Björnsson / [email protected] Assistant Editor: Singing Painting at Nylo 20 Steinunn Jakobsdóttir / [email protected] Interview with artist Ragnar Kjartansson Editorial Intern: Valgerður Þóroddsdóttir -

The Knights Eric Jacobsen, Conductor Tuesday, July 22, 2014 • 7:30PM

Our 109th Season Of free ClaSSiC al MuSiC COnCertS fOr the Pe OPle Of new Y Ork PreSentS the knights eric Jacobsen, conductor tueSdaY, julY 22, 2014 • 7:30PM The Historic Naumburg Bandshell on the Concert Ground of Central Park Please visit NAUMburgconcerts.org for more information on our series. Our next concerts of 2014 are on Tuesdays: 5 & 12 August 2014 ©Anonymous, 1930’s gouache drawing of Naumburg Orchestral of Naumburg Concert©Anonymous, 1930’s gouache drawing tueSdaY, julY 22, 2014 • 7:30pm in celebration of 109 years of Free concerts for the people of new York city - the oldest continuous free outdoor concert series in the united states Tonight’s concert is hosted by WQXR’s Annie Bergen. Due to a scheduling conflict it will not be broadcast live on classical WQXR - 105.9 FM - and via live stream at www.wqxr.org. naumburg orchestral concerts Presents the knightS GyörgY Ligeti (1923-2006) Old Hungarian Ballroom Dances i. andante ii. allegro iii. trio iV. Pochissimo meno mosso V. andantino maestoso Vi. trio Vii. allegro moderato beLa bartok (1881-1945) Divertimento for String Orchestra Sz. 113 BB. 118 i. allegro non troppo ii. Molto adagio iii. allegro assai Intermission sufjan steVens (1975) (arr. atkinson): suite from Run Rabbit Run (us Premiere) i. Year of the ox ii. enjoy Your rabbit iii. Year of our Lord iV. Year of the boar LJoVa (1978) Ori’s Fearful Symmetry igor straVinskY (1882-1971) Concerto in E-flat, “Dumbarton Oaks” i. tempo giusto ii. allegretto iii. con moto The Knights’ New York performance season is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. -

Love and Ballet at Pacific Northwest Ballet Encore Arts Seattle

June 2018 June 2018 Volume 31, No. 7 Paul Heppner Publisher Susan Peterson Design & Production Director Ana Alvira, Robin Kessler, Stevie VanBronkhorst Production Artists and Graphic Design Mike Hathaway Sales Director Brieanna Bright, Joey Chapman, Ann Manning Seattle Area Account Executives Amelia Heppner, Marilyn Kallins, Terri Reed San Francisco/Bay Area Account Executives Carol Yip Sales Coordinator Leah Baltus Editor-in-Chief Andy Fife Publisher Dan Paulus Art Director Gemma Wilson, Jonathan Zwickel Senior Editors Amanda Manitach Visual Arts Editor Paul Heppner President Mike Hathaway Vice President Kajsa Puckett Vice President, Marketing & Business Development Genay Genereux Accounting & Office Manager Shaun Swick Senior Designer & Digital Lead Barry Johnson Digital Engagement Specialist Ciara Caya Customer Service Representative & Administrative Assistant Corporate Office 425 North 85th Street Seattle, WA 98103 p 206.443.0445 f 206.443.1246 [email protected] 800.308.2898 x105 www.encoremediagroup.com Encore Arts Programs is published monthly by Encore Media Group to serve musical and theatrical events in the Puget Sound and San Francisco Bay Areas. All rights reserved. ©2018 Encore Media Group. Reproduction without written permission is prohibited. 2 PACIFIC NORTHWEST BALLET PACIFIC NORTHWEST BALLET Kent Stowell and Peter Boal June 1–10, 2018 Francia Russell Artistic Director Marion Oliver McCaw Hall Founding Artistic Directors PRINCIPALS Karel Cruz Lindsi Dec Rachel Foster Benjamin Griffiths William Lin-Yee James Moore -

Nostalgia in Indie Folk by Claire Coleman

WESTERN SYDNEY UNIVE RSITY Humanities and Communication Arts “Hold on, hold on to your old ways”: Nostalgia in Indie Folk by Claire Coleman For acceptance into the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 20, 2017 Student number 17630782 “Hold on, hold on to your old ways” – Sufjan Stevens, “He Woke Me Up Again,” Seven Swans Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. .............................................................................................. Claire Coleman Acknowledgements This thesis could not have been completed without the invaluable assistance of numerous colleagues, friends and family. The love, respect and practical support of these people, too many to name, buoyed me through the arduous privilege that is doctoral research. With special thanks to: The Supers – Dr Kate Fagan, Mr John Encarnacao and Associate Prof. Diana Blom My beloved – Mike Ford My family – Nola Coleman, Gemma Devenish, Neale Devenish, and the Fords. The proof-readers – Alex Witt, Anna Dunnill, Pina Ford, Connor Weightman and Nina Levy. My choir families – Menagerie, Berlin Pop Ensemble and Dienstag Choir Administrative staff at Western Sydney University Dr Peter Elliott Ali Kirby, Kate Ballard, Carol Shepherd, Kathryn Smith, Judith Schroiff, Lujan Cordaro, Kate Ford and the many cafes in Perth, Sydney and Berlin