History and Function of the Irish Echo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Outlet Editorial Director Name Ed. Dir. Email Address Ed

Community Outlet Editorial Director Ed. Dir. Email Ed. Dir. Phone Name Address Number African African Network Inza Dosso africvisiontv@yahoo. 646-505-9952 Television com; mmustaf25@yahoo. com African African Sun Times Abba Onyeani africansuntimes@gma973-280-8415 African African-American Steve Mallory blacknewswatch@ao 718-598-4772 Observer l.com African Afrikanspot Isseu Diouf Campbell [email protected] 917-204-1582 om African Afro Heritage Olutosin Mustapha [email protected] 718-510-5575 Magazine om African Afro Times African Afrobeat Radio / Wuyi Jacobs submissions@afrobe 347-559-6570 WBAI 99.5 FM atradio.com African Amandla Kofi Ayim kayim@amandlanew 973-731-1339 s.com African Sunu Afrik Radio El Hadji Ndao [email protected] 646-505-7487 m; sunuafrikradio@gma il.com African American Black and Brown Sharon Toomer info@blackandbrow 917-721-3150 News nnews.com African American Diaspora Radio Pearl Phillip [email protected] 718-771-0988 African American Harlem World Eartha Watts Hicks; harlemworldinfo@ya 646-216-8698 Magazine Danny Tisdale hoo.com African American New York Elinor Tatum elinor.tatum@amste 212-932-7465 Amsterdam News rdamnews.com; info@amsterdamne ws.com African American New York Beacon Miatta Smith nybeaconads@yaho 212-213-8585 o.com African American Our Time Press David Greaves editors@ourtimepre 718-599-6828 ss.com African American The Black Star News Milton Allimadi [email protected] 646-261-7566 m African American The Network Journal Rosalind McLymont [email protected] 212-962-3791 ; [email protected] Albanian Illyria Ruben Avxhiu [email protected] 212-868-2224 om; [email protected] m Arab Allewaa Al-Arabi Angie Damlaki angie_damlakhi@ya 646-707-2012 hoo.com Arab Arab Astoria Abdul Azmal arabastoria@yahoo. -

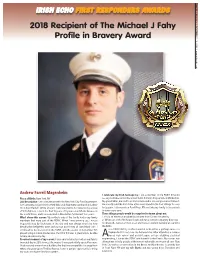

Andrew Farrell Magenheim

P a g e 1 9 / IRISH ECHO FIRST RESPONDERS AWARDS I r i s h E c h o / N O V 2018 Recipient of The Michael J Fahy E M B E R 7 - Profile in Bravery Award 1 3 , 2 0 1 8 / w w w . i r i s h e c h o . c o m Andrew Farrell Magenheim I celebrate my Irish heritage by: I am a member of the FDNY Emerald Place of Birth: New York, NY society and take part in the annual Saint Patrick's Day parade in Manhattan. Job Description: I am a lieutenant with the New York City Fire Department. My grandfather, married to an Irish citizen and is second generation himself. I am currently assigned to the third division in Manhattan and work in Ladder He proudly sold the Irish Echo at his news stand in the East Village for over 26 in East Harlem. While at work, I am responsible for supervising a crew forty years. I also reside in Pearl River, NY and take my family to the parade of 5 firefighters. I spent the first 10 years of my career on Morris Avenue in in town every year. the South Bronx, and I have worked in Manhattan for the last two years. Three things people would be surprised to know about me: Why I chose this career: My mother's side of the family had many family 1. I hold an electrical engineering degree from Cornell University members that were part of the FDNY. When I was growing up, I would 2. -

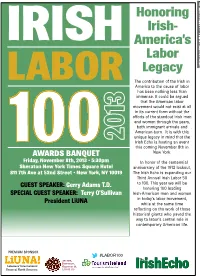

Irishecholabor100magazine

Page 17 Honoring / Irish Echo / NOVEMBER 6 - 12, 2013 / www.irishecho.com Irish- IRISH America’s Labor Legacy LABOR The contribution of the Irish in America to the cause of labor has been nothing less than immense. It could be argued that the American labor 3 movement would not exist at all 1 in its current form without the efforts of the standout Irish men and women through the years, 0 both immigrant arrivals and American-born. It is with this unique legacy in mind that the 2 Irish Echo is hosting an event this coming November 8th in AWARDS BANQUET New York. Friday, November 8th, 2013 • 5:30pm In honor of the centennial Sheraton New York Times Square Hotel anniversary of the 1913 lockout, 811 7th Ave at 52nd Street • New York, NY 10019 The Irish Echo is expanding our Third Annual Irish Labor 50 GUEST SPEAKER: Gerry Adams T.D. to 100. This year we will be honoring 100 leading SPECIAL GUEST SPEAKER: Terry O’Sullivan Irish-American men and women in today’s labor movement, President LiUNA while at the same time reflecting on the work of those historical giants who paved the way to labor’s central role in contemporary American life. PREMIUM SPONSOR #LABOR100 The ARCHER, BYINGTON, Laborers’ International GLENNON & IrishEcho Union of North America LEVINE LLP Page Page 18 IRISH LABOR 100 The Irish gave life to American labor By Terry O'Sullivan and leading various labor organizations. [email protected] For many of these warriors of the working class, their work is more than a n this centennial year of the historic job, and larger than a career; it is a Dublin Lockout, it is fitting that we lifetime's commitment. -

New York New Belfast Conference 2019 P

CHARITY PARTNER 8 1 e g a New York New Belfast Conference 2019 P / 9 1 0 2 , 8 1 - 2 1 E N U All the very best from Belfast J / o A chairde The Belfast Agenda – our targeted community h c plan - has ambitions to see a Belfast reimagined, E h s At my recent installation as Lord Mayor of Belfast, I well-connected, culturally vibrant, and a magnet for i r I spoke of my determination to build on the economic talent. And whilst building our city for its citizens, / prosperity essential to supporting peace and driving those ambitions provide a wealth of opportunities for m o c forward progress. our partners in North America and, as we have . o h That prosperity has been bolstered by the very already seen, in the beating heart of New York. c e h transatlantic partnerships that bring you together One of the many friends of Belfast, Tom diNapoli – s i r i here at the tenth New York New Belfast conference. and this year a New York New Belfast Be The Bridge . w w Forged by our community champions, in honouree – has as State Comptroller for New York w business, arts and culture, the relationships between State, explored those avenues of opportunity. With our great cities thrive and flourish in this investments in the city currently totalling (30 million environment. This is where the talking begins, where dollars) his commitment highlights the city’s the discussion and debates grow, on how our aspiration and ambition as well as its steady growth camaraderie and connections translate into mutually and success. -

Identity and Authenticity: Explorations in Native American and Irish Literature and Culture

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of April 2006 Identity and Authenticity: Explorations in Native American and Irish Literature and Culture Drucilla M. Wall University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Wall, Drucilla M., "Identity and Authenticity: Explorations in Native American and Irish Literature and Culture" (2006). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 3. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Identity and Authenticity: Explorations in Native American and Irish Literature and Culture by Drucilla Mims Wall A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College of the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English Under the Supervision of Professor Jonis Agee Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2006 ii Abstract IDENTITY AND AUTHENTICITY: EXPLORATIONS IN NATIVE AMERICAN AND IRISH LITERATURE AND CULTURE Drucilla Mims Wall, Ph.D. University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2006 Advisor: Jonis Agee This collection explores of some of the many ways in which Native American, Irish, and immigrant Irish-American cultures negotiate the complexities of how they are represented as "other," and how they represent themselves, through the literary and cultural practices and productions that define identity and construct meaning. -

Irish Echo Top 40 Under 40 2019

4 4 e g a P THE IRISH ECHO TOP 40 UNDER 40 2019 / 9 1 0 2 your potential. Stay positive. Do your Her expertise spans writing, internal , Molly Muldoon 6 2 research. Say Yes—don’t be afraid to take a communications, content marketing, social Where you live: Astoria, Queens - chance. Be aware of your weaknesses as media strategy, executive coaching, thought 0 Place of Birth: Sligo, Ireland 2 much as your strengths. My boss has a great leadership development, copy editing and Y Age: 33 R A Status: Married saying—competency, curiosity and media relations. In her current role, she U R Family: My mother Margaret is from Co. confidence will take you far. manages external communications efforts B E Three things people would be surprised to on a global scale, including publicity and F Leitrim and my father Michael is from Co. / know about me: social media strategy. She oversees major Roscommon. They both immigrated to New o 1. I met my future husband and my best communication workstreams, including h York in their twenties. They met in Gaelic c E friend (two separate people) while working executive thought leadership and client Park and moved back home after my eldest h s as a waitress in my first job in NYC. announcements. i sister was born. I am the youngest of four r I siblings and aunt to five energetic and 2. My real name is Martina. During her tenure at Siegel+Gale, her / entertaining nieces and nephews. My sisters 3. When I was a kid I made a makeshift press strategies have grown awareness of m o library above our hayshed called the the firm to help drive new business. -

Speaking Back: Queerness, Temporality, and the Irish Voice in America

Speaking Back: Queerness, Temporality, and the Irish Voice in America Gavin Doyle A Thesis submitted to the School of English at the University of Dublin, Trinity College, in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 DECLARATION I, Gavin Doyle, declare that the following thesis has not previously been submitted as an exercise for a degree, either in Trinity College, Dublin, or in any other University; that it is entirely my own work; and that the library may lend or copy it or any part thereof on request. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. Signed_____________________ Gavin Doyle i SUMMARY This thesis examines the intersections of Irishness and queerness in the work of five contemporary American writers and cultural figures: Alice McDermott, James McCourt, Peggy Shaw, Eileen Myles, and Stephanie Grant. Despite the wealth of critical scholarship in the areas of Irish-American literature and culture, the queer Irish voice in America remains almost entirely neglected. The thesis argues against the mutual trends in Irish-American and gay and lesbian cultural, social, and historical discourses that centralise “progressive” narratives in terms of socio-economic and legal advances. In so doing, the project privileges the bilateral backward glance in the writing of queer scholars such as Heather Love, José Esteban Muñoz, Elizabeth Freeman, Benjamin Kahan, Jack Halberstam, Judith Butler, and David L. Eng, and in the critical interventions of Irish and Irish-American critics who challenge the truncated “success” story of the Irish in America. -

IRISH VOICE, Wed., Oct

S2 IRISH VOICE, Wed., Oct. 7, 2009 – Tues., Oct. 13, 2009 ELCOME to our inaugural Irish degree on time here. S3 Education 100 special supple- Off I went to Trinity in the fall of 1985, and Wment of the Irish Voice. it was an adventure that I will never forget. I It seemed a natural that we should pay trib- studied Irish economics, Russian (yes, ute to the Irish who have made such an Russian!) history, Irish politics and so much indelible mark at colleges and universities more. It was an incredible year, both acade- throughout both the U.S. and Canada. Our mically and personally, and my time in diverse compilation includes presidents and Ireland firmly solidified my affection for professors, trustees and administrators and Ireland and the Irish that continues unabated everyone in between, all of whom share a to this day. common bond — a deep pride in their Our list features many educators and bene- FIRST ANNUAL shared heritage. factors of Irish Studies programs that have IRISH EDUCATION 100 There are Irish, it seems, in every corner of enriched students of all different back- SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT every school that we researched. And Irish grounds. Here in New York, Glucksman Studies programs are springing up all over Ireland House at New York University, SENIOR EDITOR the country, chock full of eager students want- founded by our honoree Loretta Brennan Debbie McGoldrick ing to immerse themselves in all things Irish. Glucksman and her late husband Lew, is a treasure trove of Irishness not only available BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT There really is nothing like flavoring a MANAGER higher education with some Irish spice. -

40 Under 40 Supplement 2014

Page 21 / Irish Echo / FEBRUARY 26 - MARCH 4, 2014 / www.irishecho.com IRISH UNDER PRESENTED BY IrishEchoThe Page 22 THE IRISH ECHO TOP 40 UNDER 40 2014 40-Under-40 reaches a magnificent seven In the blink of an eye, or so it seems, commitment is required. the Irish Echo’s 40-Under-40 Awards Dara, then, is a most worthy recip- has marked up seven years. ient of a 40-Under-40 Award. We And by dint of the forty award suspect that it will be far from the winners in each of these it’s entirely last accolade he will accrue over the appropriate to invoke the title of next few years. “magnificent seven.” As has been the case since the Unlike other Irish Echo awards awards were launched in 2008, this events held in any year’s forty are a far flung lot. Some given year, the 40- were born in Ireland, the rest in var- Under-40 are not ious parts of the United States. defined by what field At the awards event this Friday at the person works in. Rosie O’Grady’s Manhattan Club, a Rather, it is a catego- combined mileage running into the ry that is blocked off thousands will account for the pres- www.irishecho.com / Irish Echo /Ray FEBRUARY 26 - MARCH 4, 2014 O’Hanlon / at each end by age: 40 ence of award winners, their families rohanlon@ at the top and, well, and friends. irishecho.com perhaps 12 at the Some in the room will have trav- younger end (this eled from as far as Ireland and Texas. -

Diplomarbeit / Diploma Thesis

DIPLOMARBEIT / DIPLOMA THESIS Titel der Diplomarbeit / Title of the Diploma Thesis “Representation of Irish-American Identity in American and Irish-American Literature in Selected Works by James T. Farrell and Stephen Crane” verfasst von / submitted by Sophie Seidenbusch angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2019 / Vienna, 2019 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 190 299 344 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Lehramtsstudium UF Psychologie und degree programme as it appears on Philosophie UF Englisch the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Emer. o. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Waldemar Zacharasiewicz Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................. i List of Figures ............................................................................................................................ i 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 2. Theoretical Framework ................................................................................................... 4 2.1. Methodological Framework ........................................................................................ 4 2.2. (Ethnic) Identity .......................................................................................................... -

Business Wire Catalog

Full Global Comprehensive media coverage in the Americas, including the US (National Circuit), Canada and Latin America, Asia-Pacific, Europe (including saturated coverage of Central and Eastern Europe), Middle East, and Africa. Distribution to a global mobile audience via a variety of platforms and aggregators including AP Mobile, Yahoo! Finance and Viigo. Includes Full Text translations in Arabic, simplified- PRC Chinese & traditional Chinese, Czech, Dutch, French, German, Hebrew, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Slovak, Slovenian, Spanish, Thai and Turkish based on your English-language news release. Additional translation services are available. Full Global Der Standard Magazines & Periodicals Respublika All Europe Die Furche Format Telegraf Albania Die Presse New Business Vechernie Bobruisk Newspapers Heute News Vyecherny Brest 24 Orë Hrvatske Novine Profil Vyecherny Minsk Albanian Daily News Kleine Zeitung Trend Zviazda Gazeta 55 Kurier Television Zvyazda Gazeta Albania Neue Kronen Zeitung ATV Magazines & Periodicals Gazeta Ballkan Neue Kärntner Tageszeitung ORF Belarus Segodnya Gazeta Shqip Neue Vorarlberger Tageszeitung Radio Online Gazeta Shqiptare Neues Volksblatt Hitradio Ö3 bobr.by Integrimi Niederösterreichische Osterreichischer Rundfunk ORF Chapter 97 Koha Jone Nachrichten Online Computing News Metropol Oberösterreichische Ariva.de TUT.BY Panorama Nachrichten Finanzen.net Belgium Rilindja Demokratike Gazete Osttiroler Bote Finanznachrichten.de Newspapers Shekulli Salzburger Fenster Live-PR -

A Social History of the Brooklyn Irish, 1850–1900

A Social History of the Brooklyn Irish, 1850–1900 Stephen Jude Sullivan Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Stephen Jude Sullivan All rights reserved ABSTRACT A Social History of the Brooklyn Irish, 1850-1900 Stephen Jude Sullivan A full understanding of nineteenth century Irish America requires close examination of emigration as well as immigration. Knowledge of Irish pre-emigration experiences is a key to making sense of their post-emigration lives. This work analyzes the regional origins, the migration and settlement patterns, and the work and associational life of the Catholic Irish in Brooklyn between 1850 and 1900. Over this pivotal half century, the Brooklyn Irish developed a rich associational life which included temperance, Irish nationalism, land reform and Gaelic language and athletic leagues. This era marked the emergence of a more diverse, mature Irish- Catholic community, a community which responded in a new ways to a variety of internal and external challenges. To a degree, the flowering of Irish associational life represented a reaction to the depersonalization associated with American industrialization. However, it also reflected the changing cultural norms of many post-famine immigrants. Unlike their pre-1870 predecessors, these newcomers were often more modern in outlook – more committed to Irish nationhood, less impoverished, better educated and more devout. Consequently, post-1870 immigrants tended to be over-represented in the ranks of associations dedicated to Irish nationalism, Irish temperance, trade unionism, and cultural revivalism throughout Kings County.