What Is the Middle Ages/Medieval Times?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions

Scholars Crossing History of Global Missions Center for Global Ministries 2009 The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_hist Recommended Citation Fanning, Don, "The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions" (2009). History of Global Missions. 3. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_hist/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Global Ministries at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in History of Global Missions by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Middle Ages 500-1000 1 3 The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions AD 500—1000 Introduction With the endorsement of the Emperor and obligatory church membership for all Roman citizens across the empire, Roman Christianity continued to change the nature of the Church, in stead of visa versa. The humble beginnings were soon forgotten in the luxurious halls and civil power of the highest courts and assemblies of the known world. Who needs spiritual power when you can have civil power? The transition from being the persecuted to the persecutor, from the powerless to the powerful with Imperial and divine authority brought with it the inevitable seeds of corruption. Some say that Christianity won the known world in the first five centuries, but a closer look may reveal that the world had won Christianity as well, and that, in much less time. The year 476 usually marks the end of the Christian Roman Empire in the West. -

LECTURE 5 the Origins of Feudalism

OUTLINE — LECTURE 5 The Origins of Feudalism A Brief Sketch of Political History from Clovis (d. 511) to Henry IV (d. 1106) 632 death of Mohammed The map above shows to the growth of the califate to roughly 750. The map above shows Europe and the East Roman Empire from 533 to roughly 600. – 2 – The map above shows the growth of Frankish power from 481 to 814. 486 – 511 Clovis, son of Merovich, king of the Franks 629 – 639 Dagobert, last effective Merovingian king of the Franks 680 – 714 Pepin of Heristal, mayor of the palace 714 – 741 Charles Martel, mayor (732(3), battle of Tours/Poitiers) 714 – 751 - 768 Pepin the Short, mayor then king 768 – 814 Charlemagne, king (emperor, 800 – 814) 814 – 840 Louis the Pious (emperor) – 3 – The map shows the Carolingian empire, the Byzantine empire, and the Califate in 814. – 4 – The map shows the breakup of the Carolingian empire from 843–888. West Middle East 840–77 Charles the Bald 840–55 Lothair, emp. 840–76 Louis the German 855–69 Lothair II – 5 – The map shows the routes of various Germanic invaders from 150 to 1066. Our focus here is on those in dark orange, whom Shepherd calls ‘Northmen: Danes and Normans’, popularly ‘Vikings’. – 6 – The map shows Europe and the Byzantine empire about the year 1000. France Germany 898–922 Charles the Simple 919–36 Henry the Fowler 936–62–73 Otto the Great, kg. emp. 973–83 Otto II 987–96 Hugh Capet 983–1002 Otto III 1002–1024 Henry II 996–1031 Robert II the Pious 1024–39 Conrad II 1031–1060 Henry I 1039–56 Henry III 1060–1108 Philip I 1056–1106 Henry IV – 7 – The map shows Europe and the Mediterranean lands in roughly the year 1097. -

The History of Luttrellstown Demesne, Co. Dublin

NORTHERN IRELAND HERITAGE GARDENS TRUST OCCASIONAL PAPER, No 4 (2015) 'Without Rival in our Metropolitan County' - The History of Luttrellstown Demesne, Co. Dublin Terence Reeves-Smyth Luttrellstown demesne, which occupies around 600 acres within its walls, has long been recognised as the finest eighteenth century landscape in County Dublin and one of the best in Ireland. Except for the unfortunate incorporation of a golf course into the eastern portion of its historic parkland, the designed landscape has otherwise survived largely unchanged for over two centuries. With its subtle inter-relationship of tree belts and woodlands, its open spaces and disbursement of individual tree specimens, together with its expansive lake, diverse buildings and its tree-clad glen, the demesne, known as 'Woodlands' in the 19th century, was long the subject of lavish praise and admiration from tourists and travellers. As a writer in the Irish Penny Journal remarked in October 1840: ‘considered in connection with its beautiful demesne, [Luttrellstown] may justly rank as the finest aristocratic residence in the immediate vicinity of our metropolis.. in its natural beauties, the richness of its plantations and other artificial improvements, is without rival in our metropolitan county, and indeed is characterised by some features of such exquisite beauty as are rarely found in park scenery anywhere, and which are nowhere to be surpassed’.1 Fig 1. 'View on approaching Luttrellstown Park', drawn & aquatinted by Jonathan Fisher; published as plate 6 in Scenery -

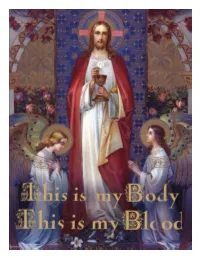

I. History of the Feast of Corpus Christi II. Theology of the Real Presence III

8 THE BEACON § JUNE 11, 2009 PASTORAL LETTER [email protected] [email protected] PASTORAL LETTER THE BEACON § JUNE 11, 2009 9 The Real Presence: Life for the New Evangelization To the priests, deacons, religious and [6] From the earliest times, the Eucharist III. Practical Reflections all the faithful: held a special place in the life of the Church. St. Ignatius, who, as a boy, had heard St. John [9] This faith in the Real Presence moves N the Solemnity of the Most preach and knew St. Polycarp, a disciple of St. us to a certain awe and reverence when we Holy Body and Blood of Christ, John, said, “I have no taste for the food that come to church. We do not gather as at a civic I wish to offer you some perishes nor for the pleasures of this life. I assembly or social event. We are coming into theological, historical and want the Bread of God which is the Flesh of the Presence of our Lord God and Savior. The O practical reflections on the Christ… and for drink I desire His Blood silence, the choice of the proper attire (i.e. not Eucharist. The Eucharist is which is love that cannot be destroyed” (Letter wearing clothes suited for the gym, for sports, “the culmination of the spiritual life and the goal to the Romans, 7). Two centuries later, St. for the beach and not wearing clothes of an of all the sacraments” (Summa Theol., III, q. 66, Ephrem the Syrian taught that even crumbs abbreviated style), even the putting aside of a. -

Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History

SOME NOTES ON MANORS & MANORIAL HISTORY BY A. HAMILTON THOMPSON, M.A.. D.Litt.. F.B.A..F.S.A. Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History By A. Hamilton Thompson, M.A., D.Litt., F.B.A., F.S.A. The popular idea of a manor assumes that it is a fixed geo graphical area with definite boundaries, which belongs to a lord with certain rights over his tenants. In common usage, we speak of this or that lordship, almost in the same way in which we refer to a parish. It is very difficult, however, to give the word an exclusively geographical meaning. If we examine one of those documents which are known as Inquisitions post mortem, for example, we shall find that, at the death of a tenant who holds his property directly from the Crown, the king's escheator will make an extent, that is, a detailed valuation, of his manors. This will consist for the most part of a list of a number of holdings with names of the tenants, specifying the rent or other services due to the lord from each. These holdings will, it is true, be generally gathered together in one or more vills or townships, of which the manor may roughly be said to consist. But it will often be found that there are outlying holdings in other vills which owe service to a manor, the nucleus of which is at some distance. Thus the members of the manor of Rothley lay scattered at various distances from their centre, divided from it and from each other by other lordships. -

Feudalism Manors

effectively defend their lands from invasion. As a result, people no longer looked to a central ruler for security. Instead, many turned to local rulers who had their Recognizing own armies. Any leader who could fight the invaders gained followers and politi- Effects cal strength. What was the impact of Viking, Magyar, and A New Social Order: Feudalism Muslim invasions In 911, two former enemies faced each other in a peace ceremony. Rollo was the on medieval head of a Viking army. Rollo and his men had been plundering the rich Seine (sayn) Europe? River valley for years. Charles the Simple was the king of France but held little power. Charles granted the Viking leader a huge piece of French territory. It became known as Northmen’s land, or Normandy. In return, Rollo swore a pledge of loyalty to the king. Feudalism Structures Society The worst years of the invaders’ attacks spanned roughly 850 to 950. During this time, rulers and warriors like Charles and Rollo made similar agreements in many parts of Europe. The system of governing and landhold- ing, called feudalism, had emerged in Europe. A similar feudal system existed in China under the Zhou Dynasty, which ruled from around the 11th century B.C.until 256 B.C.Feudalism in Japan began in A.D.1192 and ended in the 19th century. The feudal system was based on rights and obligations. In exchange for military protection and other services, a lord, or landowner, granted land called a fief.The person receiving a fief was called a vassal. -

The Legacy of the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages in the West The

The Legacy of the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages in the West The Roman Empire reigned from 27 BCE to 476 CE throughout the Mediterranean world, including parts of Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. The fall of the Roman Empire in the West in 476 CE marked the end of the period of classical antiquity and ushered in a new era in world history. Three civilizations emerged as successors to the Romans in the Mediterranean world: the Byzantine Empire (in many ways a continuation of the Eastern Roman Empire), and the civilizations of Islam and Western Europe. These three civilizations would become rivals and adversaries over the course of the succeeding centuries. They developed distinct religious, cultural, social, political, and linguistic characteristics that shaped the path each civilization would take throughout the course of the Middle Ages and beyond. The Middle Ages in European history refers to the period spanning the fifth through the fifteenth century. The fall of the Western Roman Empire typically represents the beginning of the Middle Ages. Scholars divide the Middle Ages into three eras: the Early Middle Ages (400–1000), the High Middle Ages (1000–1300), and the Late Middle Ages (1300–1500). The Renaissance and the Age of Discovery traditionally mark the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the early modern period in European history. The legacy of the Roman Empire, and the division of its territory into three separate civilizations, impacted the course of world history and continues to influence the development of each region to this day. -

June 6, 2021 FR

ST. JOSEPH CATHOLIC CHURCH / DIOCESE OF CORPUS CHRISTI 801 S. REYNOLDS ST. ALICE, TEXAS (361)664-7551 June 6, 2021 FR. CHRIS BECERRA Welcome and congratulate The Feast of Corpus Christi is celebrated to honor the Lord’s presence in the Blessed Sacrament. There were 2 separate miracles that lead to the institution of the feast in the Catholic Church: The Vision of St. Juliana of Cornillon St. Juliana had a great devotion to the Blessed Sacrament from her youth and longed for a special feast to celebrate devotion to Our Lord’s Presence in the Blessed Sacrament. The saint had a vision of the Church under the appearance of a full moon which had one dark spot. During the vision, she heard a mysterious, heavenly voice explain that the moon represented the Church at that time, and the dark spot FIRST HOLY COMMUNION symbolized the fact that a great feast in honor of the Blessed ST. JOSEPH PARISH Sacrament was missing from the liturgical calendar. St. Juliana confessed the vision to Bishop Robert de Thorete, SUNDAY, JUNE 6, 2021 then Bishop of Liège, and Jacques Pantaléon, who later became Pope Urban IV. Bishop Robert was favorably impressed and called a synod in 1246 which authorized the Monserrat Caratachea celebration of a feast dedicated to Our Lord in the Blessed Sacrament – Corpus Christi – to be held in the diocese in the Briella Renee Cardenas following year. Gabriella Celeste Garcia Eucharistic Miracle at Bolsena Fr. Pietro da Praga had grown lukewarm in his love of the Maleah Alexa Garcia Eucharist and had doubts as to whether the Eucharist was the real Body and Blood of Our Lord. -

B. Medieval Manorialism and Peasant Serfdom: the Agricultural Foundations of Medieval Feudalism Revised 21 October 2013

III. BARRIERS TO ECONOMIC GROWTH IN THE MEDIEVAL ECONOMY: B. Medieval Manorialism and Peasant Serfdom: the Agricultural Foundations of Medieval Feudalism revised 21 October 2013 Manorialism: definitions • (1) a system of dependent peasant cultivation, • in which a community of peasants, ranging from servile to free, received their lands or holdings from a landlord • - usually a feudal, military lord • (2) the peasants: worked those lands at least in part for the lord’s economic benefit • - in return for both economic and military security in holding their tenancy lands from that military lord. Medieval Manorialism Key Features • (1) European manorialism --- also known as seigniorialism [seignior, seigneur = lord] both predated and outlived feudalism: predominant agrarian socio-economic institution from 4th-18th century • (2) Medieval manorialism: links to Feudalism • The manor was generally a feudal fief • i.e., a landed estate held by a military lord in payment and reward for military services • Feudal fiefs were often collections of manors, • servile peasants provided most of labour force in most northern medieval manors (before 14th century) THE FEUDAL LORD OF THE MANOR • (1) The Feudal Lord of the Manor: almost always possessed judicial powers • secular lord: usually a feudal knight (or superior lord: i.e., count or early, duke, etc.); • ecclesiastical lord: a bishop (cathedral); abbot (monastery); an abbess (nunnery) • (2) Subsequent Changes: 15th – 18th centuries • Many manors, in western Europe, passed into the hands of non-feudal -

Monarchs During Feudal Times

Monarchs During Feudal Times At the very top of feudal society were the monarchs, or kings and queens. As you have learned, medieval monarchs were also feudal lords. They were expected to keep order and to provide protection for their vassals. Most medieval monarchs believed in the divine right of kings, the idea that God had given them the right to rule. In reality, the power of monarchs varied greatly. Some had to work hard to maintain control of their kingdoms. Few had enough wealth to keep their own armies. They had to rely on their vassals, especially nobles, to provide enough knights and soldiers. In some places, especially during the Early Middle Ages, great lords grew very powerful and governed their fiefs as independent states. In these cases, the monarch was little more than a figurehead, a symbolic ruler who had little real power. In England, monarchs became quite strong during the Middle Ages. Since the Roman period, a number of groups from the continent, including Vikings, had invaded and settled England. By the mid11th century, it was ruled by a Germanic tribe called the Saxons. The king at that time was descended from both Saxon and Norman (French) families. When he died without an adult heir, there was confusion over who should become king. William, the powerful Duke of Normandy (a part of presentday France), believed he had the right to the English throne. However, the English crowned his cousin, Harold. In 1066, William and his army invaded England. William defeated Harold at the Battle of Hastings and established a line of Norman kings in England. -

The Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages After the collapse of Rome, Western Europe entered a period of political, social, and economic decline. From about 500 to 1000, invaders swept across the region, trade declined, towns emptied, and classical learning halted. For those reasons, this period in Europe is sometimes called the “Dark Ages.” However, Greco-Roman, Germanic, and Christian traditions eventually blended, creating the medieval civilization. This period between ancient times and modern times – from about 500 to 1500 – is called the Middle Ages. The Frankish Kingdom The Germanic tribes that conquered parts of the Roman Empire included the Goths, Vandals, Saxons, and Franks. In 486, Clovis, king of the Franks, conquered the former Roman province of Gaul, which later became France. He ruled his land according to Frankish custom, but also preserved much of the Roman legacy by converting to Christianity. In the 600s, Islamic armies swept across North Africa and into Spain, threatening the Frankish kingdom and Christianity. At the battle of Tours in 732, Charles Martel led the Frankish army in a victory over Muslim forces, stopping them from invading France and pushing farther into Europe. This victory marked Spain as the furthest extent of Muslim civilization and strengthened the Frankish kingdom. Charlemagne After Charlemagne died in 814, his heirs battled for control of the In 786, the grandson of Charles Martel became king of the Franks. He briefly united Western empire, finally dividing it into Europe when he built an empire reaching across what is now France, Germany, and part of three regions with the Treaty of Italy. -

THE HIGH MIDDLE AGES the Age of Christendom

THE HIGH MIDDLE AGES 7 The Age of Christendom - 1000 - 1200AD This period in Church history is called the High very involved in four previous papacies, giving Middle Ages because of the strength of the papacy, advice on every political and religious move. the impact of several new religious orders on the life of the Church, the creation of great new centers of Gregory’s papacy is one of the most powerful in the learning with great theologians like Thomas Aquinas, history of the Church. He not only brings spiritual and the construction of hundreds of Gothic-style reform to the Church, but also gains for the Church churches. In this article, we will look at: unparalleled status and power in Europe for the next two hundred years. • Rise of the medieval papacy • Crusades Gregory’s first action is to declare that all clergy, • Inquisition including bishops, who obtained orders by simony • Mendicant friars (practice of buying or selling a holy office or • Cathedrals and universities position), are to be removed from their parishes and dioceses immediately under pain of Rise of the medieval papacy excommunication. He also insists on clerical celibacy which in most places is not being observed. The High Middle Ages is marked by the reign of several formidable popes. Many of these popes are Gregory also fights against lay investiture, the monks and part of the Cluniac reform which helps practice by which a high ranking layperson (such as tremendously to bring spiritual reform to the Church the emperor or king, count or lord) can appoint and free it from lay investiture.