Mayakovsky Discovers New York City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuban Missile Crisis JCC: USSR

asdf PMUNC 2015 Cuban Missile Crisis JCC: USSR Chair: Jacob Sackett-Sanders JCC PMUNC 2015 Contents Chair Letter…………………………………………………………………...3 Introduction……………….………………………………………………….4 Topics of Concern………………………...………………….………………6 The Space Race…...……………………………....………………….....6 The Third World...…………………………………………......………7 The Eastern Bloc………………………………………………………9 The Chinese Communists…………………………………………….10 De-Stalinization and Domestic Reform………………………………11 Committee Members….……………………………………………………..13 2 JCC PMUNC 2015 Chair’s Letter Dear Delegates, It is my great pleasure to give you an early welcome to PMUNC 2015. My name is Jacob, and I’ll be your chair, helping to guide you as you take on the role of the Soviet political elites circa 1961. Originally from Wilmington, Delaware, at Princeton I study Slavic Languages and Literature. The Eastern Bloc, as well as Yugoslavia, have long been interests of mine. Our history classes and national consciousness often paints them as communist enemies, but in their own ways, they too helped to shape the modern world that we know today. While ultimately failed states, they had successes throughout their history, contributing their own shares to world science and culture, and that’s something I’ve always tried to appreciate. Things are rarely as black and white as the paper and ink of our textbooks. During the conference, you will take on the role of members of the fictional Soviet Advisory Committee on Centralization and Global Communism, a new semi-secret body intended to advise the Politburo and other major state organs. You will be given unmatched power but also faced with a variety of unique challenges, such as unrest in the satellite states, an economy over-reliant on heavy industry, and a geopolitical sphere of influence being challenged by both the USA and an emerging Communist China. -

Geschichte & Geschichten Ein Stadtführer

Kiew Geschichte & Geschichten Ein Stadtführer Von Studierenden des Historischen Instituts der Universität Bern Inhaltsverzeichnis Scarlett Arnet Kurzes Vorwort Erinnerung an die Revolution auf dem Maidan Jacqueline Schreier Der Dnjepr Aline Misar Ein literarischer Spaziergang durch Kiew Linda Hess Jüdisches Leben Anja Schranz Holodomor Alexei Kulazhanka Kiews Leiden am Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts Architektonische Perlen des 20. Jahrhunderts Siri Funk Die Massengräber von Bykiwnja Nadine Hunziker Memorialkomplex zur Ukraine im Zweiten Weltkrieg Yannik Scheidegger „Euromaidan“: Erinnerung im Kontext der Gedenkstätte für die „Himmlische Hundertschaft“ Marie Leifeld, Dekommunisierung Natalia Berehova, Emrah Özkocagil Arnaud Dürig Leben an der Endstation Kurzes Vorwort Scarlet Arnet Im Rahmen der Veranstaltung des Historischen Instituts der Universität Bern begaben sich die Studierenden auf einer einwöchigen Exkursion nach Kiew. Während des Aufenthalts vom 02.07.2017 bis zum 08.07.2017 hatten die Studierenden Einblick in die Geschichte einer Stadt, die immer wieder im Verlauf der Zeit zentraler Ort geschichtlicher Ereignisse war. Auch im jüngsten Jahrhundert wurde Kiew zum Schauplatz wichtiger politischer Ereignisse. Auf die sogenannte Revolution der Würde in den Jahren 2013 und 2014 folgte die Krimkrise und schliesslich die Annexion der Krim durch Russland. Sowohl von jüngsten Ereignissen als auch Abbildung 1: Der Maidan und die hundertjähriger Geschichte finden sich überall in der Stadt Hinweise. Unabhängigkeitsstatue. Diesen Überresten -

Kyiv in Your Pocket, № 56 (March-May), 2014

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Hotels Kyiv March - May 2014 Orthodox Easter Ukrainian traditions Parks & Gardens The best places to experience the amazing springtime inyourpocket.com N°56 Contents ESSENTIAL CITY GUIDES Arrival & Getting around 6 Getting to the city, car rentals and transport The Basics 8 All you’d better know while in Kyiv History 11 A short overview of a rich Ukrainian history Orthodox Easter 12 Ukrainian taditions Culture & Events 14 Classical music, concerts and exhibitions schedules Where to stay 18 Kviv accommodation options Quick Picks 27 Kyiv on one page Peyzazhna Alley Wonderland Restaurants 28 The selection of the best restaurants in the city Cafes 38 Our choice from dozens of cafes Drink & Party 39 City’s best bars, pubs & clubs What to see 42 Essential sights, museums, and famous churches Parks & Gardens 50 The best place to expirience the amazing springtime Shopping 52 Where to spend some money Directory 54 Medical tourism, lifestyle and business connections Maps & Index Street register 56 City centre map 57 City map 58 A time machine at Pyrohovo open-air museum Country map 59 facebook.com/KyivInYourPocket March - May 2014 3 Foreword Spring in Kyiv usually comes late, so the beginning of March does not mean warm weather, shining sun and blossoming flowers. Kyiv residents could not be happier that spring is coming, as this past winter lasted too long. Snow fell right on schedule in December and only the last days of Febru- Publisher ary gave us some hope when we saw the snow thawing. Neolitas-KIS Ltd. -

Ukraine: Thinking Together Kyiv, 15-19 May Manifesto This Is An

Ukraine: Thinking Together Kyiv, 15-19 May Manifesto This is an encounter between those who care about freedom and a country where freedom is dearly won. This year Ukraine has seen protests, revolution, and a counter-revolution from abroad. When millions of people gathered to press for the rule of law and closer ties to Europe, the Yanukovych regime answered with violence. Vladimir Putin offered the Ukrainian government money to clear the streets and join Russia in a Eurasian project. Yanukovych criminalized civil society, which only broadened the protests. Then the police began to kill the protestors in large numbers. This brought revolution, a shift of political power to parliament, and the promise of free elections. Russian authorities reacted by invading Crimea, sending provocateurs into eastern Ukraine, threatening to dismember the country, and suppressing Russian civil society. Ukraine today, like Czechoslovakia in 1938, is a pluralist society amidst authoritarian regimes, a fascinating and troubled country poorly understood by its neighbors. It is also home to an extraordinary tradition of civil society, and to gifted writers, thinkers, and artists, many of whom, reflecting on the Maidan, have raised in new ways fundamental questions about political representation and the role of ideas in politics. In the middle of May, an international group of intellectuals will come to Kyiv to demonstrate solidarity, meet their Ukrainian counterparts, and carry out a broad public discussion about the meaning of Ukrainian pluralism for the future of Europe, Russia, and the world. The Maidan and reactions to it, in Ukraine and abroad, raise classical and contemporary questions of politics and ethics. -

Repression, Civil Conflict, and Leadership Tenure: a Case Study of Kazakhstan

Institute for International Economic Policy Working Paper Series Elliott School of International Affairs The George Washington University Repression, Civil Conflict, And Leadership Tenure: A Case Study of Kazakhstan IIEP-WP-2017-16 Susan Ariel Aaronson George Washington University September 2017 Institute for International Economic Policy 1957 E St. NW, Suite 502 Voice: (202) 994-5320 Fax: (202) 994-5477 Email: [email protected] Web: www.gwu.edu/~iiep REPRESSION, CIVIL CONFLICT, AND LEADERSHIP TENURE: A CASE STUDY OF KAZAKHSTAN Susan Ariel Aaronson, George Washington University This material is based upon work generously supported by, or in part by, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory and the U. S. Army Research Office under grant number W911NF-14-1- 0485. Table of Contents I. Kazakhstan Case Study ......................................................................................................................4 A. Overview ..........................................................................................................................................4 1. Recent History of Repression ....................................................................................................5 2. Is Kazakhstan a Dictatorship? ..................................................................................................6 II. Who are the Repressors in Kazakhstan? ......................................................................................7 III. The Role of Impunity in Kazakhstan ............................................................................................9 -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1976, No.40

www.ukrweekly.com УКРАЇНСЬКИЙ ЩОДЕННИК UKRAINIAN D A I L V VOL. LXXXIII No. 199 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, OCTOBER 17, 1976 25 CENTS Ukrainians In America Hold Xllth Congress Dr. Lev Dobriansky Re-Elected President; Structure Of UCCA Changed; Board Of Directors, Policy Council Replaced By National Council; Establish Rotation For Executive Vice-President; Nelson Rockefeller Addresses Banquet, Ford, Carter, Others Greet Congress UCCA Governing Body Presidium: President--Dr. Lev Dobriansky Executive Vice-President—Joseph Lesaywer (UNA) Vice-President-position reserved for a representative from UWA Vice-President—Very Rev. Myroslaw Charyna ("Providence") Vice-President - Wolodymyr Mazur (UNAA) Vice-President-Christine Nawrocky (UNWLA) Vice-President—Or. Michael Snihurcwych (UCCA Branches) Vice-President - Prof. Bohdan Hnatiuk (ODVVU) Vice-President—position reserved for a representative from professional organizations Vice-President-position reserved for a representative of youth organizations Vice-President-Dr. Walter Gallan (UUARC) Secretary-Ignatius Billinsky (ODFFU) Secretary—reserved for a representative from UWA Treasurer—reserved for a representative from UNA Administrative Director—Ivan Bazarko Executive Board Members: Jaroslaw Sawka—Ukrainian Hetmanite Organization of America The opening ceremonies of the Xllth Congress of Americans of Ukrainian Descent, Dr. Alexander Bilyk—("Providence") featuring the presentation of colors by SUMA youths, and the singing of the American and Prof. Edward Zarsky—Educational Council Ukrainian national anthems. Dr. Maria Kwitkowska—"Gold Cross" (Photos by J. Starostiak) Evhen Lozynskyj—Self-Reliance NEW YORK, NY.-The Xllth Congress Rockefeller, who said he asked to appear at Prof. Wasyl Omelchenko-UVAN of Americans of Ukrainian Descent, held the congressional banquet Saturday night Dr. Peter Stercho-Shevchenko Scientific Society here at the Americana Hotel Friday through and came as "a friend, a long-time friend," Lev Fuula-UNAA Sunday, October 8-Ю, re-elected Dr. -

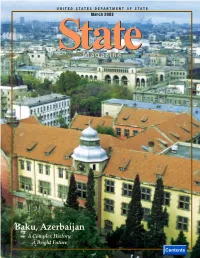

Baku, Azerbaijan a Complex History, a Bright Future in Our Next Issue: En Route to Timbuktu

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF STATE March 2003 StateStateMagazine Baku, Azerbaijan A Complex History, A Bright Future In our next issue: En Route to Timbuktu Women beating rice after harvest on the irrigated perimeter of the Niger River. Photo Trenkle Tim by State Magazine (ISSN 1099–4165) is published monthly, except State bimonthly in July and August, by the U.S. Department of State, Magazine 2201 C St., N.W., Washington, DC. Periodicals postage paid at Carl Goodman Washington, D.C., and at additional mailing locations. POSTMAS- EDITOR-IN-CHIEF TER: Send changes of address to State Magazine, HR/ER/SMG, Dave Krecke SA-1, Room H-236, Washington, DC 20522-0108. State Magazine WRITER/EDITOR is published to facilitate communication between management Paul Koscak and employees at home and abroad and to acquaint employees WRITER/EDITOR with developments that may affect operations or personnel. Deborah Clark The magazine is also available to persons interested in working DESIGNER for the Department of State and to the general public. State Magazine is available by subscription through the ADVISORY BOARD MEMBERS Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Florence Fultz Washington, DC 20402 (telephone [202] 512-1800) or on the web at CHAIR http://bookstore.gpo.gov. Jo Ellen Powell For details on submitting articles to State Magazine, request EXECUTIVE SECRETARY our guidelines, “Getting Your Story Told,” by e-mail at Sylvia Bazala [email protected]; download them from our web site Cynthia Bunton at www.state.gov/m/dghr/statemag;or send your request Bill Haugh in writing to State Magazine, HR/ER/SMG, SA-1, Room H-236, Bill Hudson Washington, DC 20522-0108. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1980, No.42

www.ukrweekly.com X "і Л - x^ СВОБОДАД,SVOBODA І І ;т О л УМРЛІНСЬКИЙ ЩОдІННИК ^!ИВ^. UKRAINIAN DAIl\ і о -- х і) roinioENGLISH-LANGUAGnE WEEKLY EDITIOWeekN l V VOL. LXXXVII. No. 21 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, OCTOBER 19, 1980 25 CENTS 13th Congress of Ukrainians of America concludes Over 20 organizations walk out of congress to protest irregularities PHILADELPHIA - Delegates of over 20 national organizations walked out of the 13th Congress of Ukrainians of America -during its concluding plenary session as a result of the elimi nation of the"rotational basis of the UCCA`s executive vice presidency and what these organizations cited as in stances of violations of the UCCA By laws and procedural inconsistencies in the conduct of the congress. The 647 delegates gathered at the congress elected" Dr. Lev Dobriansky to his 10th consecutive term asjjresideni of, the tTkr"alnmrTtongf ess"tornrnrt'tee of America and Ignatius Billinsky as executive vice president (this officer automatically serves as chairman of the UCCA National Council). Ivan Ba- zarko was re-elected administrative director. A scene during the congress plenary session. Roma Sochan Hadzewyu The congress, held Friday through Sunday, October 10-12, here at the Benjamin Franklin Hotel, was also their belief that it was purposeless for attended by some 100 guests and mem them to continue taking part in the bers of the press. congress. Formal protests about the A conflict arose immediately conduct of the congress were also Memorandum after the report of the nominations lodged by the Ukrainian National committee during the concluding ses Women's League of America and To all members of the Supreme Assembly, all branch and district officers and sion because the rotation system for the Plast Ukrainian Youth Organization. -

Marquette University Slavic Institute Papers NO. 11

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Marquette University Press Publications 1961 Marquette University Slavic Institute Papers NO. 11 Alfred J. Sokolnicki Roman Smal-Stocki Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/mupress-book MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY SLAVIC INSTITUTE PAPERS NO. 11 THE SLAVIC INSTITUTE OF MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY 1949-1961 BY ROMAN SMAL-STOCKI, PH.D. Professor of History Director, Slavic Institute AND ALFRED J. SoKOLNICKI, L.H.D. Associate Professor of Speech Secretary, Slavic Institute "The Pursuit of Truth to Make Men Free" SLAVIC INSTITUTE MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY MILWAUKEE, WISCONSIN - -----,........,,----- ' ' I. \ " THE SLA VI~ l~STl:rurE OF MARQUETTE -U.NlVERSfl'Y. l ,. l / I .- J 'I 'J:o'! ,-,. The Slavic l~tute. was·~ll:Sh~ ,t Marquette ,lhiiv~ai~ ,i~ 1949: - . r !- ' , , I , , - I. to fo~~rlthe study of the history, ;culture; an.t' -0i~op of ~ Sia~ nations through th~ organizatio? of cbUr~, ~•..,~Jr, sympoaiums, eemina~s,,.-- public C().Dferences, and publications; · - ,. • · - , , ' ~ - ' { ~ 2. to develop an appreciation of and preserve thlf cultural heritage of m~ than.14 million American citizens of Slavic ~t in' tbe spirit of the fund,. 1 mental equality of all Slavic nations t ' - \ I - ., ~ to _atfebgtbF ~crican,Slav~c cultural relatipns thr-0u,gh 1onginal contd~u. ~ to -American scholarslup. ' , , I , I vi ... I ~ ' ,, I \. ~ ' . \ . - • ~- i )\ ·- ' \ ; ' ' ./, ' \ \: . - ., !fHE- Sbt\VJC°i~~~·or -~ Q~.F;M:E UNIVERSI~ 7 t -:r ., :1 :._ -.. \ t'. r \ - \•~ .-·I - Brother Leo V, Ryan, C.S.V. -a.i,. Joseph P. Donnelly, 'SJ._ D~tor, Con~~I Edu°.8ll1 Rev. Edward Finn, S.J. - -·· • j , ' Profe880r David D. Dravea *Profeeeor Rom,nr Sm~-Stocki Profe880r '.Roman ~ko111d' Director • · Profe880r Bel. -

Occupy! Scenes from Occupied America 28 Daily Acadlemsice Bo Ork Reevievwsi Efrowm T Hoe Sfo Cbial Oscoienkcess 2012 Blog Admin

Jul Book Review: Occupy! Scenes from Occupied America 28 daily acadLemSicE bo oRk reevievwsi efrowm t hoe sfo cBial oscoienkcess 2012 Blog Admin Like 19 Tw eet 28 Share 3 In the fall of 2011, a small protest camp in downtown Manhattan exploded into a global uprising, sparked in part by what many saw as the violent overreactions of the police. Occupy! is an unofficial record of the movement and combines first-hand accounts with reflections from activist academics and writers. Jason Hickel finds the book has excellent moments of insight but thought it could benefit from a more lengthy analysis. Occupy! Scenes from Occupied America. Astra Taylor and Keith Gessen (eds). Verso. 2011. Find this book When a small group of activists first occupied Zuccotti Park in Lower Manhattan last September nobody thought it would amount to much. But it wasn’t long before Occupy Wall Street struck a chord with a nation embittered by bank bailouts, plutocracy, and rising social inequalities, galvanized hundreds of thousands of angry protestors, and inspired similar encampments in dozens of cities across the United States and Europe. As a scholar who followed OWS closely with both personal and scholarly interest, I was thrilled to get my hands on Occupy!: Scenes from Occupied America, one of the first book-length texts to have been published on the topic. Occupy! was composed in an unconventional style. It compiles 34 short chapters and dozens of sketches and photographs selected and edited by a team of eight scholar-activists, mostly from radical journals in New York such as n+1 and Dissent, led by Astra Taylor and Keith Gessen. -

The Soviet Union and the North Korean Seizure of the USS Pueblo: Evidence from Russian Archives

COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER #47 The Soviet Union and the North Korean Seizure of the USS Pueblo: Evidence from Russian Archives By Sergey S. Radchenko THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES CHRISTIAN F. OSTERMANN, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. The project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to accelerate the process of integrating new sources, materials and perspectives from the former “Communist bloc” with the historiography of the Cold War which has been written over the past few decades largely by Western scholars reliant on Western archival sources. It also seeks to transcend barriers of language, geography, and regional specialization to create new links among scholars interested in Cold War history. Among the activities undertaken by the project to promote this aim are a periodic BULLETIN to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to Cold War history; a fellowship program for young historians from the former Communist bloc to conduct archival research and study Cold War history in the United States; international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars; and publications.