Introduction: World War I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regione Friuli Venezia-Giulia S .P

2388000 2389000 2390000 2391000 Dogna C A Malborghetto Valbruna I 4 2 Moggio Udinese ¡ 6 Tarvisio Chiusaforte Resiutta Resia LEGENDA C.LE NAURAZIS Classe acustica delle unità territoriali Classe IV Classe V Fasce di pertinenza aree industriali "Forti" Fasce di classe III Fasce di classe IV Fasce di pertinenza aree industriali "Sparse" % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % A % % % % % % % % % Fasce di classe III % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % Fasce di classe IV Infrastrutture di trasporto Ferrovia Ferrovia (tratti in galleria) A Autostrada Autostrada (tratti in galleria) Strade Statali e Provinciali C Strade Statali e Provinciali (tratti in galleria) Strade Comunali 0 0 0 0 0 0 Strade Comunali di progetto 1 1 4 4 1 1 Confine comunale 5 5 C A I 4 2 5 C I P O T C A I 4 2 5 U D IN E A V O N A L A L I 2 V 3 C A I 4 2 A 5 U T O S T R A D A E T N E R R O T Sistema di riferimento: Gauss-Boaga fuso est Base cartografica: Carta Tecnica Regionale al 1:5.000 U D IN E A - U T A V T R A O V L S IS VALORI LIMITE ASSOLUTI VALORI LIMITE ASSOLUTI T A I VALORI DI QUALITÀ R O DI EMISSIONE DI IMMISSIONE A 2 Leq in dB(A) D 3 CLASSI DI DESTINAZIONI Leq in dB(A) Leq in dB(A) A D'USO DEL TERRITORIO LIMITI MASSIMI E TEMPI DI RIFERIMENTO A 0 0 0 0 0 0 Diurno (6-22) Notturno (22-6) Diurno (6-22) Notturno (22-6) Diurno (6-22) Notturno (22-6) 0 0 4 4 1 1 I aree particolarmente protette 45 35 50 40 47 37 5 5 II aree prevalentemente residenziali 50 40 55 45 52 42 A III aree di tipo misto 55 45 60 50 57 47 IV aree di intensa attività umana 60 50 65 55 62 52 C V aree prevalentemente industriali 65 55 70 60 67 57 VI aree esclusivamente industriali 65 65 70 70 70 70 C A I 6 3 8 C A I 6 3 2 REGIONE FRIULI VENEZIA-GIULIA S .P . -

CHIUSAFORTE (Ud). La Chiusa

Carta Archeologica Online del Friuli Venezia Giulia - www.archeocartafvg.it CHIUSAFORTE (Ud). La Chiusa. Località sulle rive del fiume Fella di fronte allo sbocco della Val Raccolana che ebbe fin dall'antichità una funzione strategica di controllo sulla strada che risaliva il Canal del Ferro. Il nome deriva dalla costruzione di una fortezza ("La Chiusa") voluta dal Patriarca di Aquileia (1100 circa) con la quale si imponeva il pagamento di un dazio a chi transitava. Successivamente più volte ampliata, della fortezza oggi non ci rimangono che poche tracce in prossimità del Ponte di Ferro della Ferrovia. A causa della vicinanza strategica del passo e l'interesse economico della fortezza, Chiusaforte attirò l'attenzione di tutti i dominatori del tempo e per molti secoli fu contesa dai duchi d'Austria, dai Patriarchi di Aquileia e dalla Repubblica di Venezia, subendo inoltre le invasioni turche. Una prima certezza ci viene offerta dalla via romana che univa Aquileia a Virunum, capitale amministrativa della provincia del Noricum. Questa via, di cui non conosciamo il nome, viene impropriamente detta via Iulia Augusta e risulta essere «strada di notevole peso militare dopo il I secolo d.C. e di ancor maggior importanza economica. Dunque la via romana, lungo la quale si svilupperà Chiusaforte, si presenta, in età imperiale, come un'arteria molto importante, ma gli scavi eseguiti da R. Egger e G. Piccottini sul Magdalensberg hanno evidenziato che i traffici commerciali tra Aquileia e le regioni alpine nord-orientali erano molto sviluppati già in epoca repubblicana. Di fronte alla minaccia barbara dovette intervenire l'imperatore Marco Aurelio (161-181 d.C.), il cui governo segnerà la fine del periodo aureo dell'impero. -

Cartina Cervignano Del Friuli

Udine 11 Saciletto 10 Gorizia via Viui Austria fiumeTaglio via Carnia Ss 351 via Monsignor Angelo Ramazzotti 12 Cormons via via Dai Novai fiume Ausa via Monsignor Angelo Ramazzotti via del Pradulin via Venezia via Goriziavia da l’Ara via Michelangelo via Arturo Malignani via Divisione Julia Ss 14 via Larga via Galileo Galilei Galileo via via Tagliamento viaUdine via della Colonnella via Dal Luzan via Arturo Malignani 6 Buonarroti 9 via Enrico Fermi 7 via Leonardo da Vinci 5 via della Bezzecca 13 via del Pradulin via G. B. Tiepolo via Torre via Leonardo da Vinci via Larga Udine via della Vigna P via Solferino Slovenia via San Martino Ss 14 via da l’Ara Pordenone Ss 14 via Divisione Julia via Contrade Gorizia Venezia Sarcinelli Pietro via P via Gorizia Molin dal via DoganaVecchia Muscoli via Demanio 4 Strassoldo via Pietro Sarcinelli via Monsignor Angelo Ramazzotti 8 42 Cervignano del Friuli P via Cesare Battisti via Martiri per la Libertà Scodovacca Ronchi dei 3 piazza Legionari via Trento S. Girolamo piazzale delPorto 39 via Lung’Aussa 40 via Giusto Gervasutti Giusto via via Martiri per la Libertà Trieste via Cristoforo Colombo 41 Vicolo Forno del via 24 Maggio Venezia Lung’Aussa via via Marcuzzi Montes 1 via Primo Maggio vicolo Corto via P. Zorutti v.lo Modon viale della Stazione 15 piazza Indipendenza via Marco Polo via Cavour via Nazario Sauro via G. Mazzini Trieste 2 via Roma via Giuseppe Garibaldi P via Amerigo Vespucci via 11 Febbraio via P. Mascagni p.zza Libertà p.le Papa largo G. -

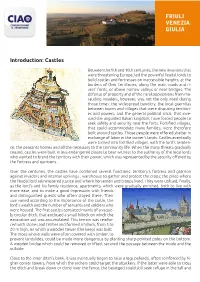

Introduction: Castles

Introduction: Castles Between the 9th and 10th centuries, the new invasions that were threatening Europe, led the powerful feudal lords to build castles and fortresses on inaccessible heights, at the borders of their territories, along the main roads and ri- vers’ fords, or above narrow valleys or near bridges. The defense of property and of the rural populations from ma- rauding invaders, however, was not the only need during those times: the widespread banditry, the local guerrillas between towns and villages that were disputing territori- es and powers, and the general political crisis, that inve- sted the unguided Italian kingdom, have forced people to seek safety and security near the forts. Fortified villages, that could accommodate many families, were therefore built around castles. Those people were offered shelter in exchange of labor in the owner’s lands. Castles eventually were turned into fortified villages, with the lord’s residen- ce, the peasants homes and all the necessary to the community life. When the many threats gradually ceased, castles were built in less endangered places to bear witness to the authority of the local lords who wanted to brand the territory with their power, which was represented by the security offered by the fortress and garrisons. Over the centuries, the castles have combined several functions: territory’s fortress and garrison against invaders and internal uprisings ; warehouse to gather and protect the crops; the place where the feudal lord administered justice and where horsemen and troops lived. They were utilised, finally, as the lord’s and his family residence, apartments, which were gradually enriched, both to live with more ease, and to make a good impression with friends and distinguished guests who often stayed there. -

COMUNE DI FIUMICELLO VILLA VICENTINA Provincia Di Udine Codice Fiscale E P.IVA 02916640309 Via Gramsci, 8 – FIUMICELLO VILLA VICENTINA - Tel

COMUNE DI FIUMICELLO VILLA VICENTINA Provincia di Udine Codice Fiscale e P.IVA 02916640309 Via Gramsci, 8 – FIUMICELLO VILLA VICENTINA - Tel. 0431/972711 - Fax 0431/969261 Posta elettronica certificata (PEC) [email protected] PROVVEDIMENTO DEL COMMISSARIO N. 90 del 21/04/2018 OGGETTO: Tassa sui Rifiuti (TARI) - Approvazione Piano Economico Finanziario e Tariffe anno 2018. IL COMMISSARIO con i poteri del Consiglio Comunale L’anno DUEMILADICIOTTO, il giorno VENTUNO del mese di APRILE alle ore 12.00 nella sede Comunale il Commissario Ennio Scridel, nominato con decreto del Presidente della Regione Autonoma Friuli Venezia Giulia n. 012/Pres. del 23 gennaio 2018, con la partecipazione del Segretario Comunale Dott.ssa Ivana Bianchi, adotta il presente atto; Vista la legge regionale 28 dicembre 2017 n. 48 avente ad oggetto “Istituzione del Comune di Fiumicello Villa Vicentina mediante fusione dei comuni di Fiumicello e Villa Vicentina, ai sensi dell’art. 7, primo comma, numero 3) dello Statuto speciale della Regione autonoma Friuli Venezia Giulia”; Accertato che il nuovo Ente è istituito con decorrenza 1° febbraio 2018; Visto l’art. 2, comma 2 della L.R. 48/2017 “Dall’1 febbraio 2018, data di istituzione del nuovo Comune del nuovo Comune di Fiumicello Villa Vicentina, prevista all’articolo 1, comma 1, i Sindaci, le Giunte e i Consigli Comunali dei Comuni di Fiumicello e Villa Vicentina cessano dalle rispettive cariche. Dalla medesima data, con decreto del Presidente della Regione, su conforme deliberazione della Giunta Regionale, sono nominati un commissario e un vicecommissario, ai quali sono conferiti i poteri esercitati dai Sindaci, dalle Giunte e dai Consigli Comunali cessati dalla carica”; Visto altresì l’art. -

Distrett0 2060 Storia Del Club 1992-93

ROTARY CLUB CERVIGNANO – PALMANOVA P.H.A. DISTRETT0 2060 STORIA DEL CLUB 1992-93 - 2001-2002 2 PREFAZIONE In questo opuscolo sono riportati gli appunti manoscritti lasciati da Vincen- zo Parmeggiani, che proseguono la storia del nostro Club giunta, nel primo fascicolo, al 25° anniversario. Ne aveva parlato in occasione della riunione del 26 settembre 2002. “Ho appena finito di buttare giù gli appunti degli ultimi dieci anni; li ho dati a Mario [Burba]; se qualcuno me li batte, perché io con computer, fax e dia- volerie del genere non sono per niente in confidenza, li rivedo…….”. Appe- na due giorni dopo, un improvviso malore lo ha colpito inesorabilmente! I suoi appunti sono stati riprodotti invariati; è sembrato giusto lasciarli con l’originale istintiva freschezza e spontaneità perché leggendoli sembrava re- almente di sentire ancora la sua voce, la sua arguzia i suoi commenti. Perché alterarli solo per ritoccarne in qualche punto la forma? Nell’opuscolo è riassunta la storia del club dal 1996 -Presidenza Comin- al 2002 –Presidenza Patamia-. Sono dieci anni della vita del Club vista con i suoi occhi: quasi un diario personale , con le sue osservazioni, le sue rifles- sioni. In quegli scritti Enzo ci appare ancora tanto vivo che il tentativo di tratteg- giarne la figura come uomo e come rotariano sarebbe del tutto superfluo e comunque incompleto. D’altronde egli stesso, inconsapevolmente, ha dato un efficace scorcio di sè in un inciso inserito nell’anno rotariano 1994-95. Verosimilmente, il Se- gretario del Club gli aveva comunicato che il Manuale di Procedura gli con- sentiva, essendo diventato “senior atti- vo”, di chiedere la dispensa dall’obbligo della frequenza. -

8A Tappa: Prato Di Resia - Dogna

INDICAZIONI DEL CAMMINO CELESTE BARBANA/AQUILEIA - MONTE LUSSARI 8a Tappa: Prato di Resia - Dogna - Punto di partenza : Prato di Resia - Punto di Arrivo: Dogna - Disl. risalite/discese: 430 m - Lunghezza : 13,4 km - Durata : ± 4,0 h Associazione ITER AQUILEIENSE - - CAMMINO CELESTE- a www.camminoceleste.eu 8 Tappa ANNO 2021 Percorsa la ciclabile prima di scendere dalla ex stazione di Dogna, vale la pena portarsi sul viadotto percorrendo altri circa 300 metri più avanti, la visione della Val Do- Segnaletica lungo il Cammino: gna con il Monte Montasio sullo sfondo ne vale la pena. NORD Con 13 km in più ci si può portare fino a Plan dei Spa- Se vuoi seguire la Via consigliata 71 del Cammino Celeste segui dovai,(+13 km) ma per le sole persone allenate ed abi- l’indicazione del pesce. tuate a fare lunghe camminate, in questo caso su asfalto e sotto la battuta di sole del pomeriggio. Itinerario della 8a Tappa Prato di Resia - Dogna Giunti a valle sulla strada di Val Raccolana si va a sini- stra superando due ponti quello del torrente Raccolana prima e del fiume Fella poi. 70 A Chiusaforte ci si porta alla vecchia stazione ferrovia- ria del paese per immettersi sulla nuova ciclabile Al- peadria realizzata lungo la vecchia linea ferroviaria, tutta asfaltata. 71 Val Dogna Scendendo nel bosco verso Val Raccolana si supera anche un ponticello lungo tre metri sotto la parete di roccia, addossato alla parete rocciosa subito prima della 69 confluenza con il sentiero 632. Superato il ponticello si raggiunge la valle lungo un bellissimo sentiero avvolto dalla vegetazione del bosco. -

Second Report Submitted by Italy Pursuant to Article 25, Paragraph 1 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities

Strasbourg, 14 May 2004 ACFC/SR/II(2004)006 SECOND REPORT SUBMITTED BY ITALY PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 25, PARAGRAPH 1 OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES (received on 14 May 2004) MINISTRY OF THE INTERIOR DEPARTMENT FOR CIVIL LIBERTIES AND IMMIGRATION CENTRAL DIRECTORATE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS, CITIZENSHIP AND MINORITIES HISTORICAL AND NEW MINORITIES UNIT FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES II IMPLEMENTATION REPORT - Rome, February 2004 – 2 Table of contents Foreword p.4 Introduction – Part I p.6 Sections referring to the specific requests p.8 - Part II p.9 - Questionnaire - Part III p.10 Projects originating from Law No. 482/99 p.12 Monitoring p.14 Appropriately identified territorial areas p.16 List of conferences and seminars p.18 The communities of Roma, Sinti and Travellers p.20 Publications and promotional activities p.28 European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages p.30 Regional laws p.32 Initiatives in the education sector p.34 Law No. 38/2001 on the Slovenian minority p.40 Judicial procedures and minorities p.42 Database p.44 Appendix I p.49 - Appropriately identified territorial areas p.49 3 FOREWORD 4 Foreword Data and information set out in this second Report testify to the considerable effort made by Italy as regards the protection of minorities. The text is supplemented with fuller and greater details in the Appendix. The Report has been prepared by the Ministry of the Interior – Department for Civil Liberties and Immigration - Central Directorate for Civil Rights, Citizenship and Minorities – Historical and new minorities Unit When the Report was drawn up it was also considered appropriate to seek the opinion of CONFEMILI (National Federative Committee of Linguistic Minorities in Italy). -

FRIULI Serving People and Far-Off Lands the Decision of the European

FRIULI Serving people and far-off lands The decision of the European institutions in the late eighties to develop a transport axis between Barcelona and Kiev created the vocation of the Friuli region to play a key role as a trading hub, with the provincial capital becoming the crossroads of the maritime route to the Mediterranean. This idea gradually developed, and was eventually expressed formally at the Pan-European Transport Conference in 1995. In parts of the region hit by industrial decline in the ’eighties, the Structural Funds helped implement the development strategy aimed at improving the infrastructures and services needed for freight transit. At the port of Trieste, which has the largest covered area for transit freight in Italy, the ERDF has funded work aimed at speeding up loading and unloading operations in the timber terminal. Some 14,700 m² of wharves have been brought into operation, improving freight moving time by 17%. The major efforts concerned Cervignano in the province of Udine, which is the hub of intermodal services in Friuli. A new railway station for container transit has been equipped for quick and efficient loading and unloading from trains to road transport vehicles and vice versa. Opened in spring 1997, but not yet working to full capacity, it covers 1 million m² and is capable of shifting 1,000 tonnes of freight daily. It consists of covered warehouses, areas for the manoeuvring and parking of articulated lorries, a repair shop and offices for management and service staff. A staff of economic promoters The ERDF has helped create a Technological Innovation Centre in Amaro, which is a mountain area in the province of Udine. -

SOCIOECONOMIC STRUCTURE of the SLOVENE POPULATION in ITALY Ales Lokar and Lee Thomas

SOCIOECONOMIC STRUCTURE OF THE SLOVENE POPULATION IN ITALY Ales Lokar and Lee Thomas Ethnic Structure of FPiuli-Venezia Giulia ~n Italy, the Slovenes live almost exclusively in the region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, which is divided politically into four provinces. Ther are, from west to south-east, Pordenone, Udine (Viden), Gorizia (Gorica) and Trieste (Trst), named after the respective provincial capitals. The regional capital is Trieste, which is also the largest city, having approximately 300,000 inhabi tants. The provinces are subdivided into comuni, roughly corresponding to American counties. Data in this study are by comuni, since they are the smallest political divi sions for which population and socioeconomic data are available. 2 The region Friuli-Venezia Giulia is inhabited by four different ethnic groups: Italians, Friulians, Slo venes and Germans. Officially, however, the ethnic com position of the region is not clearly established, as the official Italian census, carried out at ten year inter vals, does not report data by ethnic groups. This is true for the region as a whole, except for the comuni of the Trieste province, where the last two censuses (1961, 1971) did include data on the Slovene population. For the other comuni of the region only estimates are avail able, based on the work of various researchers,3 but there are no official statistics. The members of the non-Italian groups do not accept the validity of the re sults of these investigations, nor do they believe the census data where those are available. Their argument is that the census data are biased for political and socio economic reasons, that Italians are the so-called "state nation" and are politically, economically and socially dominant in the region, while the other three groups may be considered as dominated minorities. -

The Provinces of Friuli Venezia Giulia

Spring/Summer 2005 Dante Alighieri Society, Michigan Chapter Message from the President Ecco il vero volto di Dante: non aveva il naso aquilino Two thousand and four was a successful Firenze, 7 marzo 2005 - Dante Alighieri aveva il naso lungo ma non aquilino. Lo year for our Society. In addition to the rivela il più antico volto del Sommo Poeta finora documentato, di cui è stato com- cultural events, we introduced activities pletato da poco il restauro a Firenze. L'intervento sul più antico ritratto dell'autore with new formats to respond to changing della «Divina Commedia», che non doveva essere un bell'uomo, rivela anche la interests. Let us know how you liked carnagione scura e smentisce l'iconografia che si è andata affermando nei secoli, them as we need your input in planning soprattutto le immagini imposte dal Rinascimento, che lo volevano col naso aqui- successful activities. Please remember lino. È il critico d'arte Arturo Carlo Quintavalle - con un articolo sul «Corriere also that our Society offers many della Sera» - ad anticipare gli esiti di un importante restauro che sarà inaugurato volunteer opportunities in all of our fra breve nel capoluogo toscano. Il restauro affidato a Daniela Dini è stato possi- committees and that by participating you bile grazie all'impegno generoso di un privato, Umberto Montano, in accordo con will get to know other members who le soprintendenze, che ha investito 400 mila euro. L'affresco con l'immagine di share your passion for the Italian lan- Dante, risalente intorno al 1375, si trova nell'antica sede dell'Arte dei Giudici e guage and culture. -

Regione Friuli Venezia-Giulia L

2399000 2400000 2401000 2402000 2403000 B A O TARVISIO RIO R STABET TARVISIO G ¡ H Pontebba E Malborghetto Valbruna K.2 T T Tarvisio UDINE O Dogna Moggio Udinese RIO Chiusaforte MALBORGHETTO SILBER FERROVIA TESTA DI MALBORGHETTO LEGENDA ROSTA Sintesi del P.R.G.C. RIO A - Zona di interesse storico-architettonico ed ambientale RIO B - Zona di completamento e di recupero degli immobili tradizionali C - Zona di espansione K.1 A D2 - Zona industriale-artigianale L V UGOVIZZA D3 - Zona degli insediamenti industriali e artigianali esistenti ARGENTO D5 - Zona delle centraline idroelettriche 0 0 DI - Discarica di inerti 0 0 0 0 2 2 5 5 1 1 E1 - Zona di alta montagna 5 5 K.211 E2 - Zona boschiva S.S. K.212 E3 - Zona silvo-zootecnica PONTEBBANA N.13 L C A E4 - Zona agricolo-paesaggistica A N TARVISIO A ET1 - Zona di tutela ambientale di alta montagna L IL CALVARIO UDINE S.S. V EX STAZIONE DI UGOVIZZA ET2 - Zona di tutela ambientale boschiva E FERROVIA ET3 - Zona di tutela ambientale silvo-zootecnica FORTE HENSEL K.104 G2 - Zona alberghiera (RUDERI) G3 - Demanio sciabile MALBORGHETTO (SEDE COMUNALE) H2 - Zona per nuovi insediamenti commerciali e per artigianato di servizio K.210 IG - Zona ittiogenica NAZIONALE FELLA P - Attrezzature e servizi di grande interesse regionale CUCCO FIUME AC - Zona per attrezzature collettive AUTOSTRADA A 23 K.105 S.S. K.208 AD - Aree dismesse o dismettibili PONTEBBANA N.13 VIA K.209 FH - Zona del forte Hensel SA - Servizi autostradali NAZIONALE TARVISIO VP - Zona di verde privato ZR - Zona di riqualificazione del rio