2020 Netherlands Country Report | SGI Sustainable Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

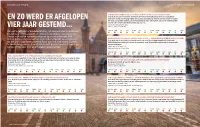

En Zo Werd Er De Afgelopen Vier Jaar Gestemd

UITKERINGSGERECHTIGDEN TWEEDE KAMER VERKIEZINGEN EEN INKOMENSAANVULLING VOOR MENSEN MET EEN MEDISCHE URENBEPERKING Deze motie beoogde te bereiken dat mensen met een beperking/handicap die naar hun maximale EN ZO WERD ER AFGELOPEN vermogen werken, een toeslag krijgen die los staat van eventueel inkomen van een partner of ouders. Dit omdat zij vanwege die medische urenbeperking dus maar een beperkt aantal uren kunnen werken en zodoende onvoldoende inkomen kunnen genereren. Stemdatum: 24 september 2019 VIER JAAR GESTEMD… Indiener: Jasper van Dijk (SP) Van extra geld voor armoedebestrijding, tot aanpassingen in de Wajong. 50PLUS CDA CU D66 DENK FvD GL PvdA PvdD PVV SGP SP VVD De afgelopen vier jaar heeft de Tweede Kamer kunnen stemmen over diverse voorstellen ter verbetering van de sociale zekerheid. FNV Uitkeringsgerechtigden heeft er acht moties uitgepikt. Groen betekent AANPASSEN WETSVOORSTEL WAJONG OM DE REGELS TE HARMONISEREN ZONDER VERSLECHTERING Deze motie was bedoeld om het alternatief zoals opgesteld door belangenorganisaties (onder wie dat een partij voor heeft gestemd. Rood was een stem tegen. Duidelijk FNV Uitkeringsgerechtigden) in de wet te verwerken, zodat de nadelige gevolgen van de harmonisatie te zien is dat geen van de moties het heeft gehaald omdat de regerings- worden voorkomen. partijen (VVD, CDA, D66 en CU) steeds tegenstemden. Stemdatum: 30 oktober 2019 Indieners: PvdA, GL, SP en 50Plus 50PLUS CDA CU D66 DENK FvD GL PvdA PvdD PVV SGP SP VVD EEN AANGESCHERPT AFSLUITINGSBELEID VOOR DRINKWATER EN WIFI Deze motie was opgesteld om naast gas en elektriciteit ook drinkwater en internet op te nemen als basis- voorziening. Dit om te voorkomen dat mensen met een betalingsachterstand in een onleefbare situatie EXTRA GELD OM DE GEVOLGEN VAN ARMOEDE ONDER KINDEREN TE BESTRIJDEN belanden als deze voorzieningen worden afgesloten. -

I&O-Zetelpeiling 15 Maart 2021

Rapport I&O-Zetelpeiling 15 maart 2021 VVD levert verder in; D66 stijgt door; Volt en Ja21 maken goede kans Colofon Maart peiling #2 I&O Research Uitgave I&O Research Piet Heinkade 55 1019 GM Amsterdam Rapportnummer 2021/69 Datum maart 2021 Auteurs Peter Kanne Milan Driessen Het overnemen uit deze publicatie is toegestaan, mits de bron (I&O Research) duidelijk wordt vermeld. 15 maart 2021 2 van 15 Inhoudsopgave Belangrijkste uitkomsten _____________________________________________________________________ 4 1 I&O-zetelpeiling: VVD levert verder in ________________________________________________ 7 VVD levert verder in, D66 stijgt door _______________________ 7 Wie verliest aan wie en waarom? _________________________ 9 Aandeel zwevende kiezers _____________________________ 11 Partij van tweede (of derde) voorkeur_______________________ 12 Stemgedrag 2021 vs. stemgedrag 2017 ______________________ 13 2 Onderzoeksverantwoording _________________________________________________________ 14 15 maart 2021 3 van 15 Belangrijkste uitkomsten VVD levert verder in; D66 stijgt door; Volt en Ja21 maken goede kans In de meest recente I&O-zetelpeiling – die liep van vrijdag 12 tot maandagochtend 15 maart – zien we de VVD verder inleveren (van 36 naar 33 zetels) en D66 verder stijgen (van 16 naar 19 zetels). Bij peilingen (steekproefonderzoek) moet rekening gehouden worden met onnauwkeurigheids- marges. Voor VVD (21,0%, marge 1,6%) en D66 (11,8%, marge 1,3%) zijn dat (ruim) 2 zetels. De verschuiving voor D66 is statistisch significant, die voor VVD en PvdA zijn dat nipt. Als we naar deze zetelpeiling kijken – 2 dagen voor de verkiezingen – valt op hoezeer hij lijkt op de uitslag van de Tweede Kamerverkiezingen van 2017. Van de winst die de VVD boekte in de coronacrisis is niets over: nu 33 zetels, vier jaar geleden ook 33 zetels. -

Free Movement and the Right to Protest

statewatch monitoring the state and civil liberties in the UK and Europe vol 13 no 1 January-February 2003 Free movement and the right to protest Information, intelligence and "personal data" is to be gathered on: potential demonstrators and other groupings expected to travel to the event and deemed to pose a potential threat to the maintenance of public law and order The freedom of movement for all EU citizens, one of its four by the unaccountable EU Police Chiefs Task Force, and the basic freedoms of the EU, is under attack when it comes to Security Office of the General Secretariat of the Council of the people exercising their right to protest. European Union (the 15 EU governments) is to "advise" on The "freedom of movement" of people is held to mean the operational plans to combat protests (see Viewpoint, page 21). right of citizens to move freely between the 15 countries of the Information, intelligence and "personal data" on: EU without being checked or controlled or having to say why potential demonstrators and other groupings expected to travel to the they are travelling. Martin Bangemann, then the EC event and deemed to pose a potential threat to the maintenance of Commissioner for the Internal Market, told the European public law and order Parliament in 1992: "We want any EC citizen to go from are to be supplied by each national police and security agency to Hamburg to London without a passport" (Statewatch, vol 2 no 6). the state where the protest is planned - on a monthly, then weekly This "freedom" was never uniformly implemented but today it and finally daily basis up to the event. -

How to Reach Younger Readers

Copenhagen Crash – may 2008 The Netherlands HowHow toto reachreach youngeryounger readersreaders HowHow toto reachreach youngeryounger readersreaders …… withwith thethe samesame contentcontent Another way to … 1. … handle news stories 2. … present articles 3. … deal with the ‘unavoidable topics’ 4. … select subjects 5. … approach your readers « one » another way to handle news stories « two » another way to present articles « three » another way to deal with the ‘unavoidable topics’ « four » another way to select subjects « five » another way to approach your readers Circulation required results 2006 45,000 2007 65,000 (break even) 2008 80,000 (profitable) 2005/Q4 2007/Q4 + / - De Telegraaf 673,620 637,241 - 36,379 5.4% de Volkskrant * 275,360 238,212 - 37,148 13.5% NRC Handelsblad * 235,350 209,475 - 25,875 11.0% Trouw * 98,458 94,309 - 4,149 4.2% nrc.next * 68,961 * = PCM Circulation 2007/Q4 DeSp!ts Telegraaf (June 1999) 637,241451,723 deMetro Volkskrant * (June 1999) 238,212538,633 NRCnrc.next Handelsblad * (March * 2006) 209,47590,493 TrouwDe Pers * (January 2007) 491,24894,309 nrc.nextDAG * * (May 2007) 400,60468,961 * = PCM Organization 180 fte NRC Handelsblad 24 fte’s for nrc.next Organization 180 fte 204 fte NRC Handelsblad NRC Handelsblad nrc.next 24 fte’s for nrc.next » 8 at central desk (4 came from NRC/H) » 5 for lay-out » other fte’s are placed at different NRC/H desks • THINK! • What is the story? • What do you want to tell? • Look at your page! Do you get it? » how is the headline? » how is the photo caption? » is everything clear for the reader? » ENTRY POINTS … and don’t forget! • Don’t be cynical or negative • Be optimistic and positive • Try to put this good feeling, this positive energy, into your paper ““IfIf youyou ’’rere makingmaking aa newspapernewspaper forfor everybodyeverybody ,, youyou ’’rere actuallyactually makingmaking aa newspapernewspaper forfor nobody.nobody. -

JA21 VERKIEZINGSPROGRAMMA 2021-2025 Het Juiste Antwoord VOORWOORD

JA21 VERKIEZINGSPROGRAMMA 2021-2025 Het Juiste Antwoord VOORWOORD Net als velen van u zou ik nergens liever willen leven dan hier. Ons mooie land heeft een gigantisch potentieel. We zijn innovatief, nuchter, hardwer- kend, trots op wie we zijn en gezegend met een indrukwekkende geschie- denis en een gezonde handelsgeest. Een Nederland dat Nederland durft te zijn is tot ongekende prestaties in staat. Al sinds de komst van Pim Fortuyn in 2002 laten miljoenen kiezers weten dat het op de grote terreinen van misdaad, migratie, het functioneren van de publieke sector en Europa anders moet. Nederland zal in een uitdijend en oncontroleerbaar Europa meer voor zichzelf moeten kiezen en vertrouwen en macht moeten terugleggen bij de kiezer. Maar keer op keer krijgen rechtse kiezers geen waar voor hun stem. Wie rechts stemt krijgt daar immigratierecords, een steeds verder uitdijende overheid, stijgende lasten, een verstikkend ondernemersklimaat, afschaffing van het referendum en een onbetaalbaar en irrationeel klimaatbeleid voor terug die ten koste gaan van onze welvaart en ons woongenot. Ons programma is een realistische conservatief-liberale koers voor ieder- een die de schouders onder Nederland wil zetten. Positieve keuzes voor een welvarender, veiliger en herkenbaarder land waarin we criminaliteit keihard aanpakken, behouden wat ons bindt en macht terughalen uit Europa. Met een overheid die er voor de burgers is en goed weet wat ze wel, maar ook juist niet moet doen. Een land waarin we hart hebben voor wie niet kan, maar hard zullen zijn voor wie niet wil. Wij zijn er klaar voor. Samen met onze geweldige fracties in de Eerste Kamer, het Europees Parlement en de Amsterdamse gemeenteraad én met onze vertegenwoordigers in de Provinciale Staten zullen wij na 17 maart met grote trots ook uw stem in de Tweede Kamer gaan vertegenwoordigen. -

Verloren Vertrouwen

ANNE BOs Verloren vertrouwen Afgetreden ministers en staatssecretarissen 1967-2002 Boom – Amsterdam Verloren vertrouwen Afgetreden ministers en staatssecretarissen 1967-2002 Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. dr. J.H.J.M. van Krieken, volgens het besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 28 maart 2018 om 14.30 uur precies door Anne Sarah Bos geboren op 25 februari 1977 te Gouda INHOUD INLEIdINg 13 Vraagstelling en benadering 14 Periodisering en afbakening 20 Bronnen 22 Opbouw 23 dEEL I gEïsOLEERd gERAAkT. AftredEN vanwegE EEN cONfLIcT IN hET kABINET 27 hOOfdsTUk 1 dE val van mINIsTER dE Block, ‘hET mEEsT gEgEsELdE werkpAARd’ VAN hET kABINET-dE JONg (1970) 29 ‘Koop prijsbewust, betaal niet klakkeloos te veel’ 32 ‘Prijzenminister’ De Block op het rooster van de oppositie 34 Ondanks prijsstop een motie van wantrouwen 37 ‘Voelt u zich een zwak minister?’ 41 De kwestie-Verolme: een zinkend scheepsbouwconcern 43 De fusie-motie: De Block ‘zwaar gegriefd’ 45 De Loonwet en de cao-grootmetaal 48 Tot slot. ‘Ik was geen “grote” figuur in de ministerraad’ 53 hOOfdsTUk 2 hET AftredEN van ‘IJzEREN AdRIAAN’ van Es, staatssEcretaris van dEfENsIE (1972) 57 De indeling van de krijgsmacht. Horizontaal of verticaal? 58 Minister De Koster en de commissie-Van Rijckevorsel 59 Van Es stapt op 62 Tot slot. Een rechtlijnige militair tegenover een flexibele zakenman 67 hOOfdsTUk 3 sTAATssEcretaris JAN GlasTRA van LOON EN dE VUILE was Op JUsTITIE (1975) 69 Met Mulder, de ‘ijzeren kanselier’, op Justitie 71 ‘Ik knap de vuile was op van anderen’ 73 Gepolariseerde reacties 79 In vergelijkbare gevallen gelijk behandelen? Vredeling en Glastra van Loon 82 Tot slot. -

Walking in the Hague

EN Walking in The Hague NINE CENTURIES OF HAGUE ARCHITECTURE A walking tour along historic and modern buildings in The Hague www.denhaag.com 1 Walking in The Hague Nine centuries of Hague architecture Welcome to The Hague. For over 400 years now, the city has been the seat of the Dutch government. Since 1981, it is a royal city again and a city of peace and justice. The Hague is more than 750 years old and has, over the last century-and-a-half, developed into a large urban conglomerate, with a great deal of activity, cultural facilities and first-rate shops. From a town of 75,000 inhabitants in 1850, The Hague has grown into the third largest city of the Netherlands with almost 500,000 inhabitants. Owing to this late but explosive growth, The Hague has very striking architecture from the 19th th and 20 century. The Hague Convention and Visitors Bureau has From 1900, the well-known architect H.P. Berlage created an interesting walk especially for lovers of (1856-1934) made his mark on the city. His brick architecture. You begin this walk of about two-and- buildings are sober in character; the decorations a-half hours on Hofweg, indicated on the map by a have been made subordinate to the architecture. We advise you to follow the route on the map. After Berlage, the architects of De Stijl and the New Of course, you can always take a break during your Realism strove for taut and functional architecture. walk for a visit to a museum or a nice cup of coffee. -

Changing Party Electorates and Economic Realignment

Changing party electorates and economic realignment Explaining party positions on labor market policy in Western Europe Dominik Geering and Silja Häusermann, University of Zurich [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Socio-structural change has led to important shifts of voters, such as middle class voters increasingly voting for the left and working class voters increasingly voting for the populist right. These electoral shifts blur the voter-party alignments, which prevailed during the post- war period. Consequently, comparative politics scholars have started to question whether parties still represent the class interests of their voters. Most contributions answer this question negatively, arguing that parties have detached themselves from the class profile of their electorates. We argue that this conclusion is erroneous as it relies on assumptions on and measures of class structuration that are outdated. We show that the class profile of party electorates still predicts parties’ positions on labor market policies. However, these voter- party alignments become observable empirically only if we a) use a post-industrial schema of class stratification to characterize party constituencies and b) distinguish between different dimensions of labor market policy, notably redistribution and activation. For our analysis we explore the class profiles of electorates and party positions on labor market policies in Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the UK. We use two sources of data: Micro-level survey data (ISSP 2000 and 2006) and a newly compiled data set on party positions during electoral campaigns in the 2000s. We have three main findings. First, we show that the distinction between working class and middle-class parties does not explain party positions anymore, because the middle class has expanded and become heterogeneous. -

NPO-Fonds Presentatie Cijfers 2018

CIJFERS 2018 Gebaseerd op 1 jaar feitelijke gegevens NPO-fonds (met uitzondering van de diverse talentontwikkelingstrajecten) !1 ALGEMEEN 2018 !2 Hoeveel aanvragen zijn er in totaal bij het NPO-fonds ingediend en toegekend? 2018 !3 TOTAAL INGEDIENDE AANVRAGEN Ontwikkeling Productie Totaal 160 153 140 120 100 89 81 80 72 60 47 40 42 40 30 24 15 20 10 9 0 Video drama Video documentaire Audio Totaal 2018 !4 TOTAAL TOEGEKENDE AANVRAGEN Ontwikkeling Productie Totaal 100 91 90 80 70 56 60 51 50 40 40 28 28 30 22 17 20 13 7 10 5 6 0 Video drama Video documentaire Audio Totaal 2018 !5 TOTAAL SLAGINGS% Ontwikkeling Productie Totaal 100% 80% 67% 67% 63% 63% 60% 59% 60% 57% 55% 54% 50% 52% 47% 40% 20% 0% Video drama Video documentaire Audio Totaal 2018 !6 Hoe is de verhouding tussen indieningen en toekenningen per omroep? 2018 !7 TOTAAL INGEDIEND PER OMROEP Ontwikkeling Productie Totaal 40 34 34 35 30 25 26 25 19 18 20 15 16 16 15 13 15 12 11 9 9 10 7 8 5 4 4 4 5 1 0 1 0 EO MAX NTR VPRO HUMAN BNNVARA AVROTROS KRO-NCRV 2018 !8 TOTAAL TOEGEKEND PER OMROEP Ontwikkeling Productie Totaal 25 20 19 20 18 18 15 13 9 10 10 9 9 10 7 8 7 5 6 5 3 3 5 2 1 0 0 0 0 EO MAX NTR VPRO HUMAN BNNVARA AVROTROS KRO-NCRV 2018 !9 2018 59% 52% 63% 69% Gemiddeld 60% 82% VPRO 80% 78% 81% NTR Totaal 0% 0% MAX 53% 50% Productie 56% !10 54% KRO-NCRV 50% OMROEP 56% HUMAN 56% Ontwikkeling 53% EO 60% 38% 75% TOTAAL SLAGINGS% PER 0% 50% BNNVARA 20% 71% AVROTROS 0% 20% 10% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% Hoeveel geld is er in totaal toegekend? 2018 !11 2018 € 15.978.099 € 8.927.107 € 7.251.100 -

Jaarverslag Vereniging Kro-Ncrv

JAARVERSLAG 2020 VERENIGING KRO-NCRV 1 Jaarverslag 2020 Inhoudsopgave Verslag van het bestuur bij de jaarrekening 2020 5 Verslag van de Raad van Toezicht 35 Jaarrekening 2020 43 Balans per 31 december 2020 44 Exploitatierekening over 2020 46 Kasstroomoverzicht over 2020 4 7 Algemene toelichting op de jaarrekening 52 Toelichting op de balans per 31 december 2020 60 Toelichting op de exploitatierekening over 2020 69 Nadere toelichtingen - Model IV - Exploitatierekening 2020 per kostendrager 82 - Model VI - Nevenactiviteiten per cluster 84 - Model VII - Sponsorbijdragen en bijdragen van derden 86 - Model VIII - Bartering 90 - Model IX - Verantwoording kosten per platform en per domein 9 1 Overige gegevens 91 Controleverklaring 92 2 Jaarverslag 2020 Jaarverslag 2020 3 1 VERSLAG VAN HET BESTUUR BIJ DE JAARREKENING 2020 The PassionJaarverslag 2020 1.1. Inleiding: het jaar 2020 en grote (sport)evenementen doorgeschoven naar van Gehandicaptenzaken, een initiatief van KRO- 3D-audiotechnieken waardoor de insectenwereld Het programma BinnensteBuiten waarin KRO-NCRV 2021. Dit bood enerzijds mogelijkheden om extra NCRV, een akkoord gekomen tussen grote belan- op unieke wijze tot leven komt en door middel van op tv, online, met (3D)podcasts en zelfs met een programma’s te maken. Anderzijds heeft dit er ook genverenigingen en de politiek om meer inclusieve Augmented Reality de insecten levensgroot in huis eigen (online) festival actief oproept om de wereld toe geleid dat er weinig ruimte was om de voorge- speeltuinen te bouwen en hebben de vragen aan kunnen worden geprojecteerd. Maar ook met het en de natuur om ons heen te ontdekken en om nomen extra investeringen in nieuw media-aanbod de Minister geresulteerd in een gebarentolk bij de You-Tube-kanaal Spot On waarbij interactie en de duurzamer te leven, is een aansprekend voorbeeld te doen en ook voor andere nieuwe initiatieven die persconferenties over de coronacrisis. -

Engineering Electoral Systems: Possibilities and Pitfalls

Alan Wall and Mohamed Salih Engineering Electoral Systems: Possibilities and Pitfalls 1 Indonesia – Voting Station 2005 Index 1 Introduction 5 2 Engineering Electoral Systems: Possibilities and Pitfalls 6 2.1 What Is Electoral Engineering? 6 2.2 Basic Terms and Classifications 6 2.3 What Are the Potential Objectives of an Electoral System? 8 3 2.4 What Is the Best Electoral System? 8 2.5 Specific Issues in Split or Post Conflict Societies 10 2.6 The Post Colonial Blues 10 2.7 What Is an Appropriate Electoral System Development or Reform Process? 11 2.8 Stakeholders in Electoral System Reform 13 2.9 Some Key Issues for Political Parties 16 3 Further Reading 18 4 About the Authors 19 5 About NIMD 20 Annex Electoral Systems in NIMD Partner Countries 21 Colophon 24 4 Engineering Electoral Systems: Possibilities and Pitfalls 1 Introduction 5 The choice of electoral system is one of the most important decisions that any political party can be involved in. Supporting or choosing an inappropriate system may not only affect the level of representation a party achieves, but may threaten the very existence of the party. But which factors need to be considered in determining an appropriate electoral system? This publication provides an introduction to the different electoral systems which exist around the world, some brief case studies of recent electoral system reforms, and some practical tips to those political parties involved in development or reform of electoral systems. Each electoral system is based on specific values, and while each has some generic advantages and disadvantages, these may not occur consistently in different social and political environments. -

Yelena Myshko (Kyiv, 1985) Is a Multidisciplinary Artist Based in Zutphen, the Netherlands

YELENA MYSHKO ////////// Ambiguous agent of change... ////////// [email protected] ////////// yelenamyshko.com Born in Kyiv, Ukraine Based in Zutphen, the Netherlands Yelena Myshko (Kyiv, 1985) is a multidisciplinary artist based in Zutphen, the Netherlands. She is exploring the social and visual phenomena of the current Zeitgeist. With both theoretical and soma immersive research methodologies she tries to find and extrapolate existential tension points within her socio-cultural environment from which she creates art and theory. AWARDS & GRANTS 2019 Kunstschouw Award, shortlisted, material prize awarded Walter Koschatzky Art-Award, nominated 2018 BLOOOM Award by Warsteiner, nominated 2017 Hendrik Muller Fonds, awarded ArtEZ Profileringsfonds, awarded 2009 HKU Jan van Scorel Fonds, awarded SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2012 Gen Y Folk: anthropology of digital culture, ROAM, Utrecht, the Netherlands (curated by Kim de Haas from Els & Nel) 2010 One Hour Art: second hour, Centraal Museum, Utrecht, the Netherlands (juried by Jos Houweling) GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2021 V International Biennial of Nude “Marko Krstov Gregović”, Public Institution Museums and galleries of Budva, Budva and Petrovac, Montenegro (curated by Dragan Mijač Brile and Milijana Istijanovic) AUSTRAL from the Virtual Realm, AUSTRAL Performance Art Festival, Buenos Aires, Argentina (curated by Hector Canonge) 2020 Wild Wild Æst, Æther Haga, the Hague, the Netherlands (curated by Marie Civikov and Voin de Voin) 2019 NULLLLL, Evenementenhal De Prodentfabriek, Amersfoort, the Netherlands