Learning Democracy from the History of Constitutional Reforms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Programs at Saint Charles Center LAKE CHARLES – the 6 to 9 P.M

The Diocese of Lake Charles lcdiocese.org Vol. 39, No. 11 Class of 2013 at St. Louis Catholic numbers 141 LAKE CHARLES -- Bishop Glen John Pro- Anna Mary Bellow, *Matthew West Berry, Mi- vost was the featured speaker at the 2013 com- chael Patrick Beverung, Kathryn Anne Bil- mencement ceremonies for 141 graduates of leaudeaux, Sarah Elizabeth Booth, Nicholas St. Louis Catholic High School. Anthony Bourdeau, Leonard Charles Breda V, In his remarks, Bishop Provost used the Sarah Elizabeth Brignac, and Jonathan Paul words of Blessed John Henry Cardinal New- Brown. man, when he told the graduates, “God has Also, Thomas Alexander Bushnell, Kelly created me to do Him some definite service; Marlin Caraway Jr, Erin Anne Casey, He has committed some work to me which *Sara Danielle Casiday, Christi Jalyn Clem- He has not committed to another; I have my ons, *Autumn Danielle Cormier, Emily Eliza- mission—I may never know it in this life, but I beth Cormier, Andrew Edward Courville, shall be told it in the next.” *Lindsey Elaine Courville, Madison Wright Continuing with the quote from Cardinal Crain, David Lyman Crawford, John Paul Newman, the Bishop said, “I am a link in the Crawford, Charles Hunter Crochet, Caterina chain, a bond of connection between persons. Marie Cuccio, and Allison Rose Cutrera. He has not created me for nothing. I shall do Christian Garrett David, Morgan Michelle good; I shall do His work. I shall be an an- Davis, Nicole Elizabeth Davis, Paula Shante gel of peace, a preacher of truth in my own DeJean, Benjamin Michael Delahoussaye, place while not intending it—if I do but keep Destinee D’Sha Delahoussaye His commandments. -

Repression of Homosexuals Under Italian Fascism

ªSore on the nation©s bodyº: Repression of homosexuals under Italian Fascism by Eszter Andits Submitted to Central European University History Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Constantin Iordachi Second Reader: Professor Miklós Lojkó CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2010 Statement of Copyright Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may be not made with the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection ii Abstract This thesis is written about Italian Fascism and its repression of homosexuality, drawing on primary sources of Italian legislation, archival data, and on the few existent (and in most of the cases fragmentary) secondary literatures on this puzzling and relatively under- represented topic. Despite the absence of proper criminal laws against homosexuality, the Fascist regime provided its authorities with the powers to realize their prejudices against homosexuals in action, which resulted in sending more hundreds of ªpederastsº to political or common confinement. Homosexuality which, during the Ventennio shifted from being ªonlyº immoral to being a real danger to the grandness of the race, was incompatible with the totalitarian Fascist plans of executing an ªanthropological revolutionºof the Italian population. Even if the homosexual repression grew simultaneously with the growing Italian sympathy towards Nazi Germany, this increased intolerance can not attributed only to the German influence. -

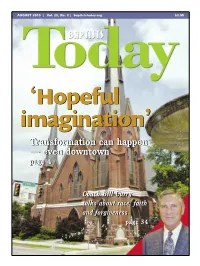

2010 Baptists Today

AUGUST 2010 | Vol. 28, No. 8 | baptiststoday.org $3.95 ‘‘HHooppeeffuull iimmaaggiinnaattiioonn ’’ TTrraannssffoorrmmaattiioonn ccaann hhaappppeenn —— eevveenn ddoowwnnttoowwnn ppaaggee 44 CCooaacchh BBiillll CCuurrrryy ttaallkkss aabboouutt rraaccee,, ffaaiitthh aanndd ffoorrggiivveenneessss ppaaggee 3344 AUGUST 2010 | Vol. 28 No. 8 John D. Pierce Baptists Today serves churches by providing a reliable source of Executive Editor [email protected] unrestricted news coverage, thoughtful analysis and inspiring Jackie B. Riley features focusing on issues of importance to Baptist Christians. Managing Editor An autonomous national [email protected] Baptist news journal Julie Steele Director of Operations and Marketing [email protected] PERSPECTIVES Keithen M. Tucker > Fostering fairness in a culture of diversity ................................7 Director of Development 13 [email protected] By John Pierce Tony W. Cartledge > Healthy families give voice to pain, fear and loss ....................8 Contributing Editor [email protected] By Paul Mullen Bruce T. Gourley > Broadway play explores evangelical faith, gay life ................16 Laxness, liability Online Editor [email protected] > Can we talk — about homosexuality? ......................................17 in the laying Vickie Frayne By Tony W. Cartledge on of hands Art Director Jannie Lister > When faithful people become friends ......................................18 Office Assistant By David M. Weatherspoon Walker Knight Jack U. Harwell Publisher Emeritus Editor Emeritus > Americans’ charitable giving draws attention ........................24 Board of Directors By Martin E. Marty Gary F. Eubanks, Marietta, Ga. (chairman) Kelly L. Belcher, Spartanburg, S.C. > Adolescent challenges no laughing matter ............................25 (vice chair) Z. Allen Abbott, Peachtree City, Ga. By Tom Ehrich Jimmy R. Allen, Big Canoe, Ga. Nannette Avery, Signal Mountain, Tenn. Ann T. Beane, Richmond, Va. Thomas E. Boland, Alpharetta, Ga. -

Harkening to the Voices of the “Lost Ones”: Attending to The

Harkening to the Voices of the “Lost Ones”: Attending to the Stories of Baptized Roman Catholics No Longer Participating in the Worship and Community Life of the Church by Bernardine Ketelaars A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of St. Michael’s College and the Toronto School of Theology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry awarded by the University of St. Michael’s College and the University of Toronto ©Copyright by Bernardine Ketelaars 2015 Harkening to the Voices of the “Lost Ones”: Attending to the Stories of Baptized Roman Catholics No Longer Participating in the Worship and Community Life of the Church Bernardine Ketelaars Doctor of Ministry University of St. Michael’s College and the University of Toronto 2015 Abstract The phenomenon of the decline in church attendance and participation has been widely recognized and a source of concern for many mainline ecclesial communities over the past number of decades. In the Roman Catholic Church, this phenomenon seemed to become more apparent following the promulgation of the documents resulting from the Second Vatican Council. Harkening to the Voices of the Lost Ones invites the reader to enter into the experiences of baptized Roman Catholics who, for whatever reason, no longer participate in the worship and community life of the Roman Catholic Church. Not wanting to presume the reasons leading to this phenomenon, I believe that it is essential to listen attentively to the lived experiences if effective outreach ministry is going to be offered to those who have withdrawn from the Church. -

National Catholic Educational Association

SEMINARY JOURNAL VOlUme eighteeN NUmber ONe SPriNg 2012 Theme: Evangelization From the Desk of the Executive Director Msgr. Jeremiah McCarthy The New Evangelization and the Formation of Priests for Today Most Rev. Edward W. Clark, S.T.D. A Worldly Priest: Evangelization and the Diocesan Priesthood Rev. Matthew Ramsay For I Was a Stranger and You Welcomed Me Cardinal Roger Mahony Teaching Catechesis to Seminarians: A Fusion of Knowledge and Pedagogy Jim Rigg, Ph.D. International Priests in the United States: An Update Rev. Aniedi Okure, O.P. Emphasizing Relationality in Distance Learning: Looking toward Human and Spiritual Formation Online Dr. Sebastian Mahfood, O.P., and Sr. Paule Pierre Barbeau, O.S.B., Ph.D. Pastoral Ministry: Receiving Even While Giving Deacon James Keating, Ph.D. On a Dominican Vision of Theological Education Ann M. Garrido, D.Min. Priest as Catechetical Leader Diana Dudoit Raiche, Ph.D. Mountain Men: Preparing Seminarians for the Spiritual Trek Sr. Mary Carroll, S.S.S.F. Virtual Reality Requiring Real Virtue Msgr. Anthony J. Ireland, S.T.D. The Heart of the Matter Most Rev. Edward Rice Catholic Ministry Formation Enrollment: Statistical Overview for 2011-2012 Mary Gautier, Ph.D. BOOK REVIEW Life and Lessons from a Warzone: A Memoir of Dr. Robert Nyeko Obol by Robert Obol Reviewed by Dr. Sebastian Mahfood, O.P., Ph.D. National Catholic Educational Association The logo depicts a sower of seed and reminds us of the derivation of the word “seminary” from the Latin word “seminarium,” meaning “a seed plot” or “a place where seedlings are nurtured and grow.” SEMINARY JOURNAL VOLUME 18 NUMBER ONE SPRING 2012 Note: Due to leadership changes in the Seminary Department, this volume was actually published in April 2013. -

2017 Annual Town Report

Important Telephone Numbers 2017 Emergencies Regular Business Fire Department 911 781-784-1522 SHARON Police Department 911 781-784-1587 Highway / Water Weekdays 781-784-1525 Nights, Weekends, Holidays 781-784-1587 2017 Annual Town Report For Questions on: Call: Phone: Animal Control Animal Control Officer 781-784-1513 Assessments/Abatements Assessor's Office 781-784-1507 x1207 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL Births/Deaths/Marriages Town Clerk 781-784-1500 x1201 Building Permits/Zoning Building Department 781-784-1525 x2310 Cable Problems Comcast 800-934-6489 Conservation/Environment Conservation Commission 781-784-1511 Dog Licenses Town Clerk 781-784-1500 x1201 Elections/Voter Registration Town Clerk 781-784-1500 x1201 Electric Permits Wiring Inspector 781-784-1525 x2310 Fire - Routine Business Fire Department 781-784-1522 Fuel Assistance Self Help, Inc. 800-225-0875 Gas Permits Gas Inspector 781-784-1525 x2310 Health Clinics Board of Health 781-784-1500 x1141 Health/Sanitation Board of Health 781-784-1500 x1206 Library Public Library 781-784-1578 Plumbing Permits Plumbing Inspector 781-784-1525 x2310 Police - Routine Business Police Department 781-784-1587 Public Assistance Transitional Assistance 800-529-1599 Recreation Recreation Department 781-784-1530 Roads/Potholes Department of Public Works 781-784-1525 x2314 Schools Superintendent's Office 781-784-1570 Seniors/Elders Council on Aging 781-784-8000 Social Services Council on Aging 781-784-8000 Taxes, Payment of Tax Collector's Office 781-784-1500 x1200 Trash/Recycling Collection Republic -

Early Modern Catholic Reform and the Synod of Pistoia Shaun London Blanchard Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Eighteenth-Century Forerunners of Vatican II: Early Modern Catholic Reform and the Synod of Pistoia Shaun London Blanchard Marquette University Recommended Citation Blanchard, Shaun London, "Eighteenth-Century Forerunners of Vatican II: Early Modern Catholic Reform and the Synod of Pistoia" (2018). Dissertations (2009 -). 774. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/774 EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY FORERUNNERS OF VATICAN II: EARLY MODERN CATHOLIC REFORM AND THE SYNOD OF PISTOIA by Shaun L. Blanchard, B.A., MSt. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2018 ABSTRACT EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY FORERUNNERS OF VATICAN II: EARLY MODERN CATHOLIC REFORM AND THE SYNOD OF PISTOIA Shaun L. Blanchard Marquette University, 2018 This dissertation sheds further light on the nature of church reform and the roots of the Second Vatican Council (1962–65) through a study of eighteenth-century Catholic reformers who anticipated Vatican II. The most striking of these examples is the Synod of Pistoia (1786), the high-water mark of “late Jansenism.” Most of the reforms of the Synod were harshly condemned by Pope Pius VI in the Bull Auctorem fidei (1794), and late Jansenism was totally discredited in the increasingly ultramontane nineteenth-century Catholic Church. Nevertheless, many of the reforms implicit or explicit in the Pistoian agenda – such as an exaltation of the role of bishops, an emphasis on infallibility as a gift to the entire church, religious liberty, a simpler and more comprehensible liturgy that incorporates the vernacular, and the encouragement of lay Bible reading and Christocentric devotions – were officially promulgated at Vatican II. -

Francis Alÿs Reel-Unreel Francis Alÿs Reel-Unreel

Between 2010 and 2014, Francis Alÿs traveled extensively to Afghanistan fol- lowing his invitation to participate in dOCUMENTA(13). This publication is a compilation of the films, paintings, drawings, collages, postcards, notebooks and other documents that make up his “Afghan Projects.” Like a storyboard or archive, their documentary yet narrative structure emerges like a travel journal with images and annotations. Including texts by Alÿs, dOCUMENTA FRANCIS ALŸS (13) curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, and several of the artist’s main col- FRANCIS ALŸS REEL-UNREEL laborators, it offers rare insights into a country in transition, so often misrep- resented in the media, as well as a nuanced debate about the relevance of contemporary art in the context of war. Alÿs’s engagement with Afghanistan has continued past the opening of dOCUMENTA (13)—in Spring 2013, he served as embedded war artist with UK’s Task Force Helmand, and the Afghan Projects continue to occupy an important part of his practice. This publication accompanies the exhibition Francis Alÿs: REEL-UNREEL at Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Donnaregina-Madre (14 June - 22 Septem- ber 2014) and Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle (10 October 2014 - 11 January 2015). List of contributors: Francis Alÿs, Fabio Cavallucci, REEL-UNREEL Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Mariam Ghani, Ewa Gorza˛dek, Ajmal Maiwandi, Amanullah Mojadidi, Robert Slifkin, Michael Taussig, Mario Garcia Torres, and Andrea Viliani. Tra il 2010 e il 2014, dopo aver accettato l’invito a partecipare a dOCUMENTA (13), Francis Alÿs ha viaggiato a lungo in Afghanistan. In questo libro sono raccolti i film, i dipinti, i disegni, i collage, le cartoline e i taccuini che compongono i suoi Afghan Projects. -

United Nations and World Health Organisation Engagement In

Di ers seas im e e & Fisichella, J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism 2017, 7:4 h P z l a A r k f i n o DOI: 10.4172/2161-0460.1000347 Journal of s l o a n n r i s u m o J ISSN: 2161-0460 Alzheimer’s Disease & Parkinsonism Conference Proceedings Open Access United Nations and World Health Organisation Engagement in Treating Global Mental Health, with a Special Focus on Dementia Daniela Fisichella* University of Catania, Italy, Department of Social and Political Science (DSPS), Italy Abstract A sharp attention is devoted to mental health and mental illness by International Law and many International Organizations (IO’s) in XXI century. As a consequence of human rights huge extension, mental health is nowadays a target of international efforts striving to address both States national choices and international achievements. World Health Organization (WHO) is expressly engaged, but United Nations (UN) opened up the legal path in early nineties, by UN General Assembly (UNGA) 46/119 of 17 December 1991, The protection of persons with mental illness and the improvement of mental health care, where mental health care and facilities are pointed out; and if mental illness couldn’t be defined, Principle 4 (Determination of mental illness) of this Resolution is crucial to direct next improvements layout. From there, UN and WHO have been carrying on a unique approach to mental health, as proved by binding and non-binding international acts, surveys, guidelines – as the 2010 WHO mhGAP Intervention Guide, now updated in its 2016 version – adopted as a result of States consultation. -

Ital-News-Number 60-FINAL.Qxp

ITALIAN POLITICS & SOCIETY The Review of the Conference Group on Italian Politics and Society No. 60, Spring 2005 http://www.congrips.org P R E S I D E N T C O N T E N T S Carol Mershon University of Virginia Symposium V I C E P R E S I D E N T Raffaella Nanetti University of Illinois Temi e Voci E X E C U T I V E S E C R E T A R Y / T R E A S U R E R Richard Katz Epistulae The Johns Hopkins University P R O G R A M C H A I R Research Dossier Carolyn Warner Arizona State University E X E C U T I V E C O M M I T T E E Note e Notizie Franklin Adler Macalester College Maurizio Cotta Book Essay and Reviews Università di Siena Julia Lynch University of Pennsylvania Membership Survey Simona Piattoni Università di Trento Supplement Alan Zuckerman Brown University C O - E D I T O R S Anthony C. Masi Filippo Sabetti Department of Sociology Department of Political Science McGill University McGill University 855 Sherbrooke St. West 855 Sherbrooke St. West Montreal,Quebec Montreal, Quebec Canada H3A 2T7 Canada H3A 2T7 [email protected] [email protected] A C K N O W L E D G E M E N T S This issue of Italian Politics and Society has been published ITALIAN POLITICS & SOCIETY with the support of McGill The Review of the Conference Group on Italian Politics and Society University No. -

Title Listings

Listing by Title Title Document Source Author Category 101 Questions and Answers on Paul Witherup, Ronald SC Abandonment to Divine Providence deD. Caussade, Jean- PR Abba! Father! A Personal Catechism O'Mahony,Pierre Gerald PR Abbey of Gethsemane - Place of Peace and Paradox (The) Aprile, Dianne VO Abbey: A Story of Discovery (The) Martin, James OT Abortion and Healing - A Cry to be Whole Ma nnion, Michael PS Abraham, Loved By God - A Contemporary Companion to the Bible Gaubert,T. Henri SC Academics at Christendom - An Introduction Christe ndom OT Achievement of Karl Rahner (The) Roberts,College Louis TH Acts of the Apostles - Catholic Scripture Study International - Notebook Winslow, Fr. SC Acts(The) of the Apostles (The) Hahn,Patrick Scott (and SC Addresses and Homilies Given in Brazil (The) Address NationalCurtis Mitch) Catholic DO Addresses and Homilies Given in West Germany (The) Address NationalNews Service Catholic DO Addresses of His Holiness Pope John Paul II to the United States Bushops Address NCCBNews Service - National DO Adolescence:During Their etcWhat's a Parent to Do? Parsons,Conference Richard of D. MA Adopted Family - Book 1: You and Your Child - A Guide for Adoptive Rondell, Catholic BishopsFlorence MA AdoptedParents Family - Book 2: The Family That Grew Rondell,(and Ruth Florence Michaels) MA Adult Christ at Christmas - Essays on the Three Biblical Christmas Stories Brown,(and Ruth Raymond Michaels) E. SC Adult(An) Christ at Christmas - Essays on the Three Biblical Christmas Stories Brown, Raymond E. SC Advent(An) is for Children - Stories, Activities, Prayers Kelemen, Julie YO Affirming the Human and the Holy Agudo, Philomena PR After Jesus - The Triumph of Jesus Reader's Digest CH Agony of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane (The) Pio of Pietrelcina, ST AHG in the Catholic Church CD AmericanPadre Heritage YO Alert to God's Word - Ready-to-Read Scripture Guides For Weekday Miles,Girls Cassian A. -

Picciotto ECSP-LG13-73

If not for profit, for what and how? Social entrepreneurship and confiscated mafia properties in Italy Loredana PICCIOTTO Business Administration, University of Palermo EMES-SOCENT Conference Selected Papers, no. LG13-73 4th EMES International Research Conference on Social Enterprise - Liege, 2013 Interuniversity Attraction Pole (IAP) on Social Enterprise (SOCENT) 2012-2017 and © Loredana Picciotto ( [email protected] ) 2013. EMES-SOCENT Conference Selected Papers are available on the EMES website (www.emes.net ) and on the SOCENT website ( www.iap-socent.be ). These papers do not undergo any editing process. They are published with the support of the Belgian Science Policy Office, within an Interuniversity Attraction Pole (IAP) on social enterprise entitled “If not for profit, for what? And how?”. 1. INTRODUCTION In the 1980s and 1990s new entrepreneurial dynamics emerged in the third sector as response to the challenges of modern socio-economic context. Indeed, social enterprises arose primarily in response to social needs not adequately met, or not met at all, by public services or for profit enterprises (Borzaga and Defourny, 2001). That is because they provide goods and services which the market or public sector is unwilling or unable to provide. In the European context, the process of institutionalization of social enterprises has often been closely linked to the evolution of public policies, especially considering the structural unemployment and the need to reduce state budget deficits (Defourny, Nyssens, 2010). In this sense, the entrepreneurship policy has been characterized by measures that promote the transition from unemployment to self-employment, used as a tool to actively intervene in the labor market (Román et al., 2013).