Zhang Dali, Huang Zhiyang, Fong Chung-Ray Asia Art Archive’S Mapping Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2018–2019 Artmuseum.Princeton.Edu

Image Credits Kristina Giasi 3, 13–15, 20, 23–26, 28, 31–38, 40, 45, 48–50, 77–81, 83–86, 88, 90–95, 97, 99 Emile Askey Cover, 1, 2, 5–8, 39, 41, 42, 44, 60, 62, 63, 65–67, 72 Lauren Larsen 11, 16, 22 Alan Huo 17 Ans Narwaz 18, 19, 89 Intersection 21 Greg Heins 29 Jeffrey Evans4, 10, 43, 47, 51 (detail), 53–57, 59, 61, 69, 73, 75 Ralph Koch 52 Christopher Gardner 58 James Prinz Photography 76 Cara Bramson 82, 87 Laura Pedrick 96, 98 Bruce M. White 74 Martin Senn 71 2 Keith Haring, American, 1958–1990. Dog, 1983. Enamel paint on incised wood. The Schorr Family Collection / © The Keith Haring Foundation 4 Frank Stella, American, born 1936. Had Gadya: Front Cover, 1984. Hand-coloring and hand-cut collage with lithograph, linocut, and screenprint. Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960 / © 2017 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 12 Paul Wyse, Canadian, born United States, born 1970, after a photograph by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, American, born 1952. Toni Morrison (aka Chloe Anthony Wofford), 2017. Oil on canvas. Princeton University / © Paul Wyse 43 Sally Mann, American, born 1951. Under Blueberry Hill, 1991. Gelatin silver print. Museum purchase, Philip F. Maritz, Class of 1983, Photography Acquisitions Fund 2016-46 / © Sally Mann, Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery © Helen Frankenthaler Foundation 9, 46, 68, 70 © Taiye Idahor 47 © Titus Kaphar 58 © The Estate of Diane Arbus LLC 59 © Jeff Whetstone 61 © Vesna Pavlovic´ 62 © David Hockney 64 © The Henry Moore Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 65 © Mary Lee Bendolph / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York 67 © Susan Point 69 © 1973 Charles White Archive 71 © Zilia Sánchez 73 The paper is Opus 100 lb. -

Booxter Export Page 1

Cover Title Authors Edition Volume Genre Format ISBN Keywords The Museum of Found Mirjam, LINSCHOOTEN Exhibition Soft cover 9780968546819 Objects: Toronto (ed.), Sameer, FAROOQ Catalogue (Maharaja and - ) (ed.), Haema, SIVANESAN (Da bao)(Takeout) Anik, GLAUDE (ed.), Meg, Exhibition Soft cover 9780973589689 Chinese, TAYLOR (ed.), Ruth, Catalogue Canadian art, GASKILL (ed.), Jing Yuan, multimedia, 21st HUANG (trans.), Xiao, century, Ontario, OUYANG (trans.), Mark, Markham TIMMINGS Piercing Brightness Shezad, DAWOOD. (ill.), Exhibition Hard 9783863351465 film Gerrie, van NOORD. (ed.), Catalogue cover Malenie, POCOCK (ed.), Abake 52nd International Art Ming-Liang, TSAI (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover film, mixed Exhibition - La Biennale Huang-Chen, TANG (ill.), Catalogue media, print, di Venezia - Atopia Kuo Min, LEE (ill.), Shih performance art Chieh, HUANG (ill.), VIVA (ill.), Hongjohn, LIN (ed.) Passage Osvaldo, YERO (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover 9780978241995 Sculpture, mixed Charo, NEVILLE (ed.), Catalogue media, ceramic, Scott, WATSON (ed.) Installaion China International Arata, ISOZAKI (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover architecture, Practical Exhibition of Jiakun, LIU (ill.), Jiang, XU Catalogue design, China Architecture (ill.), Xiaoshan, LI (ill.), Steven, HOLL (ill.), Kai, ZHOU (ill.), Mathias, KLOTZ (ill.), Qingyun, MA (ill.), Hrvoje, NJIRIC (ill.), Kazuyo, SEJIMA (ill.), Ryue, NISHIZAWA (ill.), David, ADJAYE (ill.), Ettore, SOTTSASS (ill.), Lei, ZHANG (ill.), Luis M. MANSILLA (ill.), Sean, GODSELL (ill.), Gabor, BACHMAN (ill.), Yung -

General Interest

GENERAL INTEREST GeneralInterest 4 FALL HIGHLIGHTS Art 60 ArtHistory 66 Art 72 Photography 88 Writings&GroupExhibitions 104 Architecture&Design 116 Journals&Annuals 124 MORE NEW BOOKS ON ART & CULTURE Art 130 Writings&GroupExhibitions 153 Photography 160 Architecture&Design 168 Catalogue Editor Thomas Evans Art Direction Stacy Wakefield Forte Image Production BacklistHighlights 170 Nicole Lee Index 175 Data Production Alexa Forosty Copy Writing Cameron Shaw Printing R.R. Donnelley Front cover image: Marcel Broodthaers,“Picture Alphabet,” used as material for the projection “ABC-ABC Image” (1974). Photo: Philippe De Gobert. From Marcel Broodthaers: Works and Collected Writings, published by Poligrafa. See page 62. Back cover image: Allan McCollum,“Visible Markers,” 1997–2002. Photo © Andrea Hopf. From Allan McCollum, published by JRP|Ringier. See page 84. Maurizio Cattelan and Pierpaolo Ferrari, “TP 35.” See Toilet Paper issue 2, page 127. GENERAL INTEREST THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART,NEW YORK De Kooning: A Retrospective Edited and with text by John Elderfield. Text by Jim Coddington, Jennifer Field, Delphine Huisinga, Susan Lake. Published in conjunction with the first large-scale, multi-medium, posthumous retrospective of Willem de Kooning’s career, this publication offers an unparalleled opportunity to appreciate the development of the artist’s work as it unfolded over nearly seven decades, beginning with his early academic works, made in Holland before he moved to the United States in 1926, and concluding with his final, sparely abstract paintings of the late 1980s. The volume presents approximately 200 paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints, covering the full diversity of de Kooning’s art and placing his many masterpieces in the context of a complex and fascinating pictorial practice. -

Ohio Shanghai India's Temples

fall/winter 2019 — $3.95 Ohio Fripp Island Michigan Carnival Mardi Gras New Jersey Panama City Florida India’s Temples Southwestern Ontario Shanghai 1 - CROSSINGS find your story here S ome vacations become part of us. The beauty and Shop for one-of-a-kind Join us in January for the 6th Annual Comfort Food Cruise. experiences come home with us and beckon us back. Ohio’s holiday gifts during the The self-guided Cruise provides a tasty tour of the Hocking Hills Hocking Hills in winter is such a place. Breathtaking scenery, 5th Annual Hocking with more than a dozen locally owned eateries offering up their outdoor adventures, prehistoric caves, frozen waterfalls, Hills Holiday Treasure classic comfort specialties. and cozy cabins, take root and call you back again and Hunt and enter to win again. Bring your sense of adventure and your heart to the one of more than 25 To get your free visitor’s guide and find out more about Hocking Hills and you’ll count the days until you can return. prizes and a Grand the Comfort Food Cruise and Treasure Hunt call or click: Explore the Hocking Hills, Ohio’s Natural Crown Jewels. Prize Getaway for 4. 1-800-Hocking | ExploreHockingHills.com find your story here S ome vacations become part of us. The beauty and Shop for one-of-a-kind Join us in January for the 6th Annual Comfort Food Cruise. experiences come home with us and beckon us back. Ohio’s holiday gifts during the The self-guided Cruise provides a tasty tour of the Hocking Hills Hocking Hills in winter is such a place. -

Shanghai Metro Map 7 3

January 2013 Shanghai Metro Map 7 3 Meilan Lake North Jiangyang Rd. 8 Tieli Rd. Luonan Xincun 1 Shiguang Rd. 6 11 Youyi Rd. Panguang Rd. 10 Nenjiang Rd. Fujin Rd. North Jiading Baoyang Rd. Gangcheng Rd. Liuhang Xinjiangwancheng West Youyi Rd. Xiangyin Rd. North Waigaoqiao West Jiading Shuichan Rd. Free Trade Zone Gucun Park East Yingao Rd. Bao’an Highway Huangxing Park Songbin Rd. Baiyin Rd. Hangjin Rd. Shanghai University Sanmen Rd. Anting East Changji Rd. Gongfu Xincun Zhanghuabang Jiading Middle Yanji Rd. Xincheng Jiangwan Stadium South Waigaoqiao 11 Nanchen Rd. Hulan Rd. Songfa Rd. Free Trade Zone Shanghai Shanghai Huangxing Rd. Automobile City Circuit Malu South Changjiang Rd. Wujiaochang Shangda Rd. Tonghe Xincun Zhouhai Rd. Nanxiang West Yingao Rd. Guoquan Rd. Jiangpu Rd. Changzhong Rd. Gongkang Rd. Taopu Xincun Jiangwan Town Wuzhou Avenue Penpu Xincun Tongji University Anshan Xincun Dachang Town Wuwei Rd. Dabaishu Dongjing Rd. Wenshui Rd. Siping Rd. Qilianshan Rd. Xingzhi Rd. Chifeng Rd. Shanghai Quyang Rd. Jufeng Rd. Liziyuan Dahuasan Rd. Circus World North Xizang Rd. Shanghai West Yanchang Rd. Youdian Xincun Railway Station Hongkou Xincun Rd. Football Wulian Rd. North Zhongxing Rd. Stadium Zhenru Zhongshan Rd. Langao Rd. Dongbaoxing Rd. Boxing Rd. Shanghai Linping Rd. Fengqiao Rd. Zhenping Rd. Zhongtan Rd. Railway Stn. Caoyang Rd. Hailun Rd. 4 Jinqiao Rd. Baoshan Rd. Changshou Rd. North Dalian Rd. Sichuan Rd. Hanzhong Rd. Yunshan Rd. Jinyun Rd. West Jinshajiang Rd. Fengzhuang Zhenbei Rd. Jinshajiang Rd. Longde Rd. Qufu Rd. Yangshupu Rd. Tiantong Rd. Deping Rd. 13 Changping Rd. Xinzha Rd. Pudong Beixinjing Jiangsu Rd. West Nanjing Rd. -

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction The name Shanghai still conjures images of romance, mystery and adventure, but for decades it was an austere backwater. After the success of Mao Zedong's communist revolution in 1949, the authorities clamped down hard on Shanghai, castigating China's second city for its prewar status as a playground of gangsters and colonial adventurers. And so it was. In its heyday, the 1920s and '30s, cosmopolitan Shanghai was a dynamic melting pot for people, ideas and money from all over the planet. Business boomed, fortunes were made, and everything seemed possible. It was a time of breakneck industrial progress, swaggering confidence and smoky jazz venues. Thanks to economic reforms implemented in the 1980s by Deng Xiaoping, Shanghai's commercial potential has reemerged and is flourishing again. Stand today on the historic Bund and look across the Huangpu River. The soaring 1,614-ft/492-m Shanghai World Financial Center tower looms over the ambitious skyline of the Pudong financial district. Alongside it are other key landmarks: the glittering, 88- story Jinmao Building; the rocket-shaped Oriental Pearl TV Tower; and the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The 128-story Shanghai Tower is the tallest building in China (and, after the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the second-tallest in the world). Glass-and-steel skyscrapers reach for the clouds, Mercedes sedans cruise the neon-lit streets, luxury- brand boutiques stock all the stylish trappings available in New York, and the restaurant, bar and clubbing scene pulsates with an energy all its own. Perhaps more than any other city in Asia, Shanghai has the confidence and sheer determination to forge a glittering future as one of the world's most important commercial centers. -

Land Reformation and Environmental Upgrading In

World Expo 2010 was held in Shanghai, China. The theme Land reformation and of the exposition is "Better City – Better Life" and signifies Shanghai's new status in the 21st century as a major economic environmental upgrading in the and cultural center. The Expo took place from May 1 to October World Expo in Shanghai (Part 1) 31, 2010 It is expected more than 55% of the world population will be (Land Formation and Development for living in cities by 2015. The theme of the Expo is thus trying to the venue of 2010 World Expo) display urban civilisation to the full extent, exchange their experiences of urban development, disseminate advanced notions on cities and explore new approaches to human habitat, lifestyle and working conditions in the new century. It also Presentation for HKIE Seminar demonstrates how future city can create an eco-friendly society Environmental, CAD & AMC and maintain the sustainable development of human beings 25 March 2017 therein. Within the history of World Expo since 1851, the site for the World Expo 2010 in Shanghai is considered to be Making use of the opportunity accompanied with the unique and made a number of records. For example, it World Expo development, the Municiple government of located in the most congested population zone within a Shanghai planned to restructure and upgrade the entire mega city. The site is situated on the edge of the built-up city to fit the new global standards in terms of urban, area of Shanghai only 3.5 km away from the city centre. cultural, economical and environmental quality and get herself ready to meet any new challenges. -

Hou Beiren at 100 百岁北人百岁北人 Contents

Hou Beiren at 100 百岁北人百岁北人 Contents Director’s Preface 5 Celebrating Hou Beiren at 100 7 Mark Dean Johnson My One Hundred Years: An Artistic Journey 13 Hou Beiren Plates 19 Biography 86 3 Director’s Preface Two years ago, at the opening of Sublimity: Recent Works by Hou Beiren, I proposed a toast to Master Hou: “… it was not in the plan prior to this moment, but I hope to present another exhibition of your works two years from now to celebrate your 100th birthday.” Master Hou was a little surprised by my proposal but replied affirmatively right at the moment. Thus we are having this current exhibition – Hou Beiren at 100. In the long course of human history, 100 years is just a blink of the eye. Yet when it comes to a man, 100 years is certainly a magnificent journey, especially considering the vast era of tremendous socio-political changes in modern China that Hou’s life and times encompass. Growing up as a village boy in a small county of Northern China, Hou had lived in China, Japan, and Hong Kong before relocating to the US sixty years ago. Witnessing the ups and downs, whether first-hand in China, or as a sojourner overseas, Hou never gave up his passion for painting. In fact, through painting he had been searching for his “dream”, “ideal” and “soul”, as he wrote in his statement. The mountains and valleys, rivers and creeks, trees and flowers, clouds and mists, waterfalls and rains, are all his heartfelt expressions in the means of ink and colors, and the yearning for a homeland in his dream. -

PPT 0326 Julie Chun

China Art Museum (2012) Power Station of Art (2012) 2011-2019 Natural History Museum (RelocateD 2015) State & Liu Haisu Art Museum (ReloCateD 2016) Shanghai Museum of Glass (2011) Private art Long Museum PuDong (2012) OCAT Art Terminal Shanghai (2012) museums in Shanghai Himalayas Museum (2012) Aurora Museum (2013) Shanghai K11 Art Museum (2013) Chronus Art Center (2013) 21st Century Minsheng Art Museum (2014) Long Museum West BunD (2014) Yuz Museum (2014) Mingyuan Contemporary Art Museum (2015) Shanghai Center of Photography (2015) Modern Art Museum (2016) How Museum Shanghai (2017) Powerlong Art Museum (2017) Fosun FounDation Art Center (2017) Qiao Zhebing Oil Tank Museum (2019) SSSSTART Museum (under Construction) PompiDou Shanghai (unDer ConstruCtion) China Art Museum (2012) Power Station of Art (2012) 2011-2019 Natural History Museum (RelocateD 2015) State & Liu Haisu Art Museum (ReloCateD 2016) Shanghai Museum of Glass (2011) Private art Long Museum PuDong (2012) OCAT Art Terminal Shanghai (2012) museums in Shanghai Himalayas Museum (2012) Aurora Museum (2013) Shanghai K11 Art Museum (2013) Chronus Art Center (2013) 21st Century Minsheng Art Museum (2014) Long Museum West BunD (2014) Yuz Museum (2014) Mingyuan Contemporary Art Museum (2015) Shanghai Center of Photography (2015) Modern Art Museum (2016) How Museum Shanghai (2017) Powerlong Art Museum (2017) Fosun FounDation Art Center (2017) Qiao Zhebing Oil Tank Museum (2019) SSSSTART Museum (under Construction) PompiDou Shanghai (unDer ConstruCtion) Art for the Public Who is the ”public”? Who “speaks” for the public? On what authority? What is the viewers’ reception? And, does any of this matter? Sites for public art in Shanghai (Devoid of entry fee, open access to public) Funded by the city Shanghai Sculpture Space (est. -

China Shanghai 中国上海

Erfahrungsbericht China Shanghai 中国上海 Tongji Universit¨at - Wintersemester 17/18 同济大学 Marius 小马 29. Dezember 2017 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einfuhrung¨ ................................................ 1 1.1 Vorstellung und Vorwort ............................... 1 1.2 Motivation .......................................... 2 2 Vorbereitungen ............................................ 3 2.1 Bewerbung - Deutschland (Hannover) ..................... 3 2.2 Stipendium....................................... 4 2.3 Bewerbung - Tongji (China, Shanghai) . 5 2.4 Unterkunft ........................................ 6 2.5 Visum ............................................. 7 2.6 Kreditkarte....................................... 8 2.7 Handy/Internet ...................................... 9 2.7.1 VPN (Virtual Private Network) . 9 2.7.2 NutzlicheApps¨ ................................... 9 2.8 Auslandskrankenversicherung ......................... 10 2.9 Bedingungen des Prufungsamtes¨ und andere Heimuni spezifische Angelegenheiten ............................. 10 2.10 Flug............................................. 10 3 Erste Schritte vor Ort ..................................... 11 3.1 Registrierung an der Tongji Universit¨at . 11 3.2 Handyvertrag und Internet ............................. 12 3.3 Transport .......................................... 12 3.3.1 Metro........................................... 12 3.3.2 Busse........................................... 13 3.3.3 Taxi............................................. 13 3.3.4 Fahrrad . 13 3.3.5 Scooter ......................................... -

YANG YONGLIANG Born 1980; Shanghai

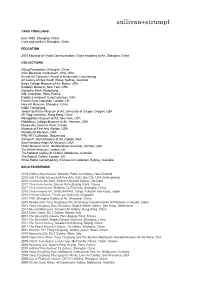

YANG YONGLIANG Born 1980; Shanghai, China Lives and works in Shanghai, China EDUCATION 2003 Bachelor of Visual Communication, China Academy of Art, Shanghai, China COLLECTIONS AiLing Foundation, Shanghai, China Allen Memorial Art Museum, Ohio, USA Arendt Art Collection, Arendt & Medernach, Luxembourg Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia Bates College Museum of Art, Maine, USA Brooklyn Museum, New York, USA Deutsche Bank, Hong Kong DSL Collection, Paris, France Fidelity Investment Corp Collection, USA Franks-Suss Collection, London, UK How Art Museum, Shanghai, China HSBC Hong Kong Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon, Oregon, USA M+ Sigg Collection, Hong Kong, China Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA Middlebury College Museum of Art, Vermont, USA Musée de L'homme, Paris, France Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA Nevada Art Museum, USA PAE ART Collection, Switzerland Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art, Florida, USA San Francisco Asian Art Museum, USA Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita State University, Kansas, USA The British Museum, London, UK The National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia The Saatchi Gallery, London, UK White Rabbit Contemporary Chinese Art Collection, Sydney, Australia SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Artificial Wonderland, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, New Zealand 2018 Salt 14 Utah Museum of Fine Arts, Salt Lake City, USA (forthcoming) 2018 Journey to the Dark, Sullivsn+Strumpf Sydney, Australia 2017 Time Immemorial, Galerie Paris-Beijing, Paris, France 2017 Time Immemorial, Matthew Liu Fine Arts, -

Chinese Experimental Art in the 1990S an Overview of Contemporary

NOVEMBER 2002 FALL ISSUE Chinese Experimental Art in the 1990s An Overview of Contemporary Taiwanese Art Contemporary Art with Chinese Characteristics The Long March Project 2002 Zunyi International Symposium US$10.00 NT$350.00 YISHU: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art Volume 1, Number 3, Fall/November 2002 Katy Hsiu-chih Chien Ken Lum Zheng Shengtian Julie Grundvig Paloma Campbell Larisa Broyde Joyce Lin Kaven Lu Judy Andrews, Ohio State University John Clark, University of Sydney Lynne Cooke, Dia Art Foundation Okwui Enwezor, Curator, Art Institute of Chicago Britta Erickson, Independent Scholar & Curator Fan Di An, Central Academy of Fine Arts Fei Dawei, Independent Curator Gao Minglu, New York State University Hou Hanru, Independent Curator & Critic Katie Hill, Independent Critic & Curator Martina Köppel -Yang, Independent Critic & Historian Sebastian Lopez, Gate Foundation and Leiden University Lu Jie, Independent Curator Ni Tsai Chin, Tunghai University Apinan Poshyananda, Chulalongkorn University Chia Chi Jason Wang, Art Critic & Curator Wu Hung, University of Chicago Art & Collection Group Ltd. Leap Creative Group Raymond Mah Gavin Chow Jeremy Lee Karmen Lee Chong-yuan Image Ltd., Taipei - Yishu is published quarterly in Taipei, Taiwan, and edited in Vancouver, Canada. From 2003, the publishing date of Yishu will be March, June, September, and December. Advertising inquiries may be sent to our main office in Taiwan: Taipei: Art & Collection Ltd. 6F, No. 85, Section 1, Chunshan North Road, Taipei, Taiwan. Phone: (886) 2-2560-2220 Fax: (886) 2-2542-0631 e-mail: [email protected] Subscription and editing inquiries may be sent to our Vancouver office: Vancouver: Yishu 1008-808 Nelson Street Vancouver, B.C.