November/December 2015 Volume 14, Number 6 Inside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zhang Hongtu / Hongtu Zhang: an Interview'

An Interview with Zhang Hongtu 281 the roots - Chinese culture - had already become part of my life just as a tail is a part of a dog's body. I'm like a dog: the tail will be with me for 10 ever, no matter where I go. Sure, after nine years away from China, I forget many things, like I forget that when you buy lunch you have to pay Zhang Hongtu / Hongtu Zhang: ration coupons with the money, and how much political pressure there An Interview' was in my everyday life. But because I still keep reading Chinese books and thinking about Chinese culture, and especially because I have the opportunity to see the differences between Chinese culture and the Western culture which I learned about after I left China, my image of Chinese culture has become more clear. Su Dongpo (the poet, I036- Zhang Hongtu was born in Gansu province, in northwest China, in lIOI) said: Bu shi Lushan zhen mianmu / Zhi yuan shen zai si shan I943, but grew up in Beijing. After studies at the Central Academy of zbong, Which means, one can't see the image of Mt. Lu because one is Arts and Crafts in Beijing, he was later assigned to work as a design inside the mountain. Now that I'm outside of the mountain, I can see supervisor in a jewellery company. In I982, he left China to pursue a what the image of the mountain is, so from this point of view I would say career as a painter in New York. -

Booxter Export Page 1

Cover Title Authors Edition Volume Genre Format ISBN Keywords The Museum of Found Mirjam, LINSCHOOTEN Exhibition Soft cover 9780968546819 Objects: Toronto (ed.), Sameer, FAROOQ Catalogue (Maharaja and - ) (ed.), Haema, SIVANESAN (Da bao)(Takeout) Anik, GLAUDE (ed.), Meg, Exhibition Soft cover 9780973589689 Chinese, TAYLOR (ed.), Ruth, Catalogue Canadian art, GASKILL (ed.), Jing Yuan, multimedia, 21st HUANG (trans.), Xiao, century, Ontario, OUYANG (trans.), Mark, Markham TIMMINGS Piercing Brightness Shezad, DAWOOD. (ill.), Exhibition Hard 9783863351465 film Gerrie, van NOORD. (ed.), Catalogue cover Malenie, POCOCK (ed.), Abake 52nd International Art Ming-Liang, TSAI (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover film, mixed Exhibition - La Biennale Huang-Chen, TANG (ill.), Catalogue media, print, di Venezia - Atopia Kuo Min, LEE (ill.), Shih performance art Chieh, HUANG (ill.), VIVA (ill.), Hongjohn, LIN (ed.) Passage Osvaldo, YERO (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover 9780978241995 Sculpture, mixed Charo, NEVILLE (ed.), Catalogue media, ceramic, Scott, WATSON (ed.) Installaion China International Arata, ISOZAKI (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover architecture, Practical Exhibition of Jiakun, LIU (ill.), Jiang, XU Catalogue design, China Architecture (ill.), Xiaoshan, LI (ill.), Steven, HOLL (ill.), Kai, ZHOU (ill.), Mathias, KLOTZ (ill.), Qingyun, MA (ill.), Hrvoje, NJIRIC (ill.), Kazuyo, SEJIMA (ill.), Ryue, NISHIZAWA (ill.), David, ADJAYE (ill.), Ettore, SOTTSASS (ill.), Lei, ZHANG (ill.), Luis M. MANSILLA (ill.), Sean, GODSELL (ill.), Gabor, BACHMAN (ill.), Yung -

General Interest

GENERAL INTEREST GeneralInterest 4 FALL HIGHLIGHTS Art 60 ArtHistory 66 Art 72 Photography 88 Writings&GroupExhibitions 104 Architecture&Design 116 Journals&Annuals 124 MORE NEW BOOKS ON ART & CULTURE Art 130 Writings&GroupExhibitions 153 Photography 160 Architecture&Design 168 Catalogue Editor Thomas Evans Art Direction Stacy Wakefield Forte Image Production BacklistHighlights 170 Nicole Lee Index 175 Data Production Alexa Forosty Copy Writing Cameron Shaw Printing R.R. Donnelley Front cover image: Marcel Broodthaers,“Picture Alphabet,” used as material for the projection “ABC-ABC Image” (1974). Photo: Philippe De Gobert. From Marcel Broodthaers: Works and Collected Writings, published by Poligrafa. See page 62. Back cover image: Allan McCollum,“Visible Markers,” 1997–2002. Photo © Andrea Hopf. From Allan McCollum, published by JRP|Ringier. See page 84. Maurizio Cattelan and Pierpaolo Ferrari, “TP 35.” See Toilet Paper issue 2, page 127. GENERAL INTEREST THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART,NEW YORK De Kooning: A Retrospective Edited and with text by John Elderfield. Text by Jim Coddington, Jennifer Field, Delphine Huisinga, Susan Lake. Published in conjunction with the first large-scale, multi-medium, posthumous retrospective of Willem de Kooning’s career, this publication offers an unparalleled opportunity to appreciate the development of the artist’s work as it unfolded over nearly seven decades, beginning with his early academic works, made in Holland before he moved to the United States in 1926, and concluding with his final, sparely abstract paintings of the late 1980s. The volume presents approximately 200 paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints, covering the full diversity of de Kooning’s art and placing his many masterpieces in the context of a complex and fascinating pictorial practice. -

24-25 IIAS 69 2.Indd

The Newsletter | No.69 | Autumn 2014 24 | The Focus 798: the re-evaluation of Beijing’s industrial heritage in the IN MANY COUNTRIES OF THIS AREA, industrialisation is still Eff ectively, after a few years of artistic activities, the SSG, As testifi ed by a UNESCO report on the an ongoing process, often the outcome of a colonial domain, a state-owned enterprise, had a plan approved by the city and presents many dark sides, such as pollution, environmental government to turn this area into a “heaven for new technology 1 Asia-Pacifi c region, the preservation of degradation and labour exploitation. Countries that have only and commerce” – the Zhongguacun Electronics Park – by 2005,4 recently achieved a high level of industrialisation, consider it too and to develop the rest of the land into high-rise modern apart- industrial heritage in Asia is still at an early recent to be worth preserving. In fact, the World Heritage List ments.5 This project would refl ect the ‘old glories’ of the factory. counts only two industrial heritage sites in the whole Asia-Pacifi c As a consequence, the owners decided to evict the artists because stage of application, and constitutes a region.3 However, this does not mean that industrial heritage the plans involved destroying the old buildings. Outraged by has been completely disregarded or abandoned in Asia. On the the threats of eviction and joining an emerging social concern controversial topic for many countries contrary, there are several stimulating instances of preservation in China against the demolition of ancient structures disguised of these kinds of structures; among them is a current trend that as urban renewal, the artists, who believed the buildings had an belonging to this region. -

Summer 2020 Degrees Conferred

THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SUMMER SEMESTER 2020 Data as of November 17, 2020 Australia Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor Fofanah, Osman Ngunnawal 2913 Bachelor of Science in Education THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY OSAS - Analysis and Reporting November 17, 2020 Page 1 of 42 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SUMMER SEMESTER 2020 Data as of November 17, 2020 Bangladesh Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor Helal, Abdullah Al Dhaka 1217 Master of Science Alam, Md Shah Comilla 3510 Master of Science THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY OSAS - Analysis and Reporting November 17, 2020 Page 2 of 42 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SUMMER SEMESTER 2020 Data as of November 17, 2020 Bolivia Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor Arrueta Antequera, Lourdes Delta El Alto Master of Science THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY OSAS - Analysis and Reporting November 17, 2020 Page 3 of 42 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SUMMER SEMESTER 2020 Data as of November 17, 2020 Brazil Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor dos Santos Marques, Ana Carolina Sao Jose Do Rio Pre 15015 Doctor of Philosophy Marotta Gudme, Erik Rio De Janeiro 22460 Bachelor of Science in Business Administration Magna Cum Laude Pereira da Cruz Benetti, Lucia Porto Alegre 90670 Doctor -

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-Making

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 6 Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Antoinette, Michelle, author. Title: Contemporary Asian art and exhibitions : connectivities and world-making / Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner. ISBN: 9781925021998 (paperback) 9781925022001 (ebook) Subjects: Art, Asian. Art, Modern--21st century. Intercultural communication in art. Exhibitions. Other Authors/Contributors: Turner, Caroline, 1947- author. Dewey Number: 709.5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover illustration: N.S. Harsha, Ambitions and Dreams 2005; cloth pasted on rock, size of each shadow 6 m. Community project designed for TVS School, Tumkur, India. © N.S. Harsha; image courtesy of the artist; photograph: Sachidananda K.J. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Introduction Part 1 — Critical Themes, Geopolitical Change and Global Contexts in Contemporary Asian Art . 1 Caroline Turner Introduction Part 2 — Asia Present and Resonant: Themes of Connectivity and World-making in Contemporary Asian Art . 23 Michelle Antoinette 1 . Polytropic Philippine: Intimating the World in Pieces . 47 Patrick D. Flores 2 . The Worlding of the Asian Modern . -

The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin

“Art Is to Sacrifice One’s Death”: The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin by Muyun Zhou Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Carlos Rojas, Supervisor ___________________________ Eileen Chow ___________________________ Leo Ching Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Critical Asian Humanities in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2021 ABSTRACT “Art Is to Sacrifice One’s Death”: The Aesthetic and Ethic of the Chinese Diasporic Artist Mu Xin by Muyun Zhou Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Carlos Rojas, Supervisor ___________________________ Eileen Chow ___________________________ Leo Ching An abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Critical Asian Humanities in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2021 Copyright by Muyun Zhou 2021 Abstract In his world literature lecture series running from 1989 to 1994, the Chinese diasporic writer-painter Mu Xin (1927-2011) provided a puzzling proposition for a group of emerging Chinese artists living in New York: “Art is to sacrifice.” Reading this proposition in tandem with Mu Xin’s other comments on “sacrifice” from the lecture series, this study examines the intricate relationship between aesthetics and ethics in Mu Xin’s project of art. The question of diasporic positionality is inherent in the relationship between aesthetic and ethical discourses, for the two discourses were born in a Western tradition, once foreign to Mu Xin. -

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-Making

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 6 Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Antoinette, Michelle, author. Title: Contemporary Asian art and exhibitions : connectivities and world-making / Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner. ISBN: 9781925021998 (paperback) 9781925022001 (ebook) Subjects: Art, Asian. Art, Modern--21st century. Intercultural communication in art. Exhibitions. Other Authors/Contributors: Turner, Caroline, 1947- author. Dewey Number: 709.5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover illustration: N.S. Harsha, Ambitions and Dreams 2005; cloth pasted on rock, size of each shadow 6 m. Community project designed for TVS School, Tumkur, India. © N.S. Harsha; image courtesy of the artist; photograph: Sachidananda K.J. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Introduction Part 1 — Critical Themes, Geopolitical Change and Global Contexts in Contemporary Asian Art . 1 Caroline Turner Introduction Part 2 — Asia Present and Resonant: Themes of Connectivity and World-making in Contemporary Asian Art . 23 Michelle Antoinette 1 . Polytropic Philippine: Intimating the World in Pieces . 47 Patrick D. Flores 2 . The Worlding of the Asian Modern . -

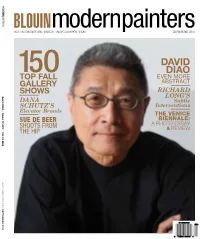

David Diao’S Singular Abstraction by Mostafa Heddaya | Portrait by Kristine Larsen

modern painters BLOUINmodernpainters SEPTEMBER 2015 DAVID 15O DIAO TOP FALL EVEN MORE GALLERY ABSTRACT SHOWS RICHArd DAVI LONG’S D DANA Subtle D IAO IAO SCHUTZ’S Interventions / D Elevator Brawls ANA SCHUTZ THE VENICE SUE DE BEER BIENNALE: SHOOTS FROM A PHOTO ESSAY / & REVIEW SUE THE HIP D E BEER BLOUINARTINFO.COM SEPTEMBER 2015 SEPTEMBER fine lines tracing five decades of david diao’s singular abstraction by mostafa heddaya | portrait by kristine larsen David Diao’s 1972 acrylic on canvas Triptych, part of his 2014 retrospective at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut. 56 MODERN PAINTERS SEPTEMBER 2015 BLOUINARTINFO.COM tracing five decades of david diao’s singular abstraction BLOUINARTINFO.COM SEPTEMBER 2015 MODERN PAINTERS 57 Union after the first semester, because I felt it was taking away “Robert Smithson would from my studio time,” he says. In 1965 Diao settled into a 22- by-147-foot loft on Canal Street, and the following year, when the always say to me, ‘David, Kootz Gallery closed, he went freelance, working as a handler and installer, even storing artworks for various galleries in his you’re a smart cookie, why cavernous apartment. And so he came to share the space with works like Franz Kline’s monumental Cardinal, a painting he are you still painting?’” would later reference in his own work (the floor plan of that loft, recalls David Diao, who at 72 is still painting. This commitment too, would eventually surface in Diao’s art). His coffee table to canvas is, in fact, a rare constant in Diao’s career, now in for some time was a Tony Smith Corten steel box. -

Ma Desheng – Curriculum Vitae

Ma Desheng – Curriculum Vitae Timeline 1952 Born in Beijing, China 1986 Moved to Paris Solo Exhibitions 2014 Black‧White‧Grey: Solo exhibition of Ma Desheng (Works of 1979-2013), Kwai Fung Hin Art Gallery, Hong Kong 2013 Selected Works, Gallery Rossi-Rossi, London 2011 Ma Desheng: Beings of Peter, Breath of Life, Asian Art Museum, Nice, France Museum Cernuschi, Paris 2010 Story of Stone: solo exhibition of Ma Desheng, organised by Kwai Fung Hin Art Gallery, Hong Kong Arts Centre, Hong Kong 2007 Ma Desheng, Galerie Jacques Barrere, Paris 2006 Faceted Symphony : solo exhibition of Ma Desheng, University Museum and Art Gallery, the University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong 2001 Ma Desheng, Michael Goedhuis, New York 1999 The Paintings of Ma Desheng, Gallery Michael Goedhuis, London 1986 Prints by Ma Desheng, FIAP (engravings), Paris Selected Group Exhibitions 2016 M+ Sigg Collection, Four Decades of Chinese Contemporary Art, Artistree, Hong Kong 2013 Gallery Magda Danysz, Paris Voice of the Unseen – Chinese Independent Art Since 1979, Arsenale (Organised by Guangdong Museum of Art), Venice, Italy 2012 Gallery Frank Pages, Switzerland Art Miami, USA 2011 Blooming in the Shadows: Unofficial Chinese Art, 1974–1985, China Institute, New York Chinese Artists in Paris 1920-1958: from Lin Fengmian to Zao Wou-ki, Musée Cernuschi, Paris, France 2009 The Biennial exhibition, Yerres, France 2008 Foire de Paris, represented by Lasés Gallery, Grand Palais, Paris Go China! Exhibition, Groninger Museum, Les Pays-Bas, The Netherlands 2007 Foire de Paris, represented -

A Transnational Feminist Study on the Woman's Historical Novel By

University of Alberta Writing Back Through Our Mothers: A Transnational Feminist Study on the Woman’s Historical Novel by Tegan Zimmerman A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Comparative Literature ©Tegan Zimmerman Fall 2013 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. For my grandmother and my mother … ABSTRACT This transnational feminist study on the contemporary woman’s historical novel (post 1970) argues that the genre’s central theme and focus is the maternal. Analyzing the maternal, disclosed through a myriad of genealogies, voices, and figures, reveals that the historical novel is a feminist means for challenging historical erasures, silences, normative sexuality, political exclusion, divisions of labour, and so on within a historical-literary context. The novels surveyed in this work speak from the margins and spaces of silence within history and the genre. As much as the works contest masculinist master narratives, they also create and envision new genealogies. -

Chinese Contemporary Art-7 Things You Should Know

Chinese Contemporary Art things you should know By Melissa Chiu Contents Introduction / 4 1 . Contemporary art in China began decades ago. / 14 2 . Chinese contemporary art is more diverse than you might think. / 34 3 . Museums and galleries have promoted Chinese contemporary art since the 1990s. / 44 4 . Government censorship has been an influence on Chinese artists, and sometimes still is. / 52 5 . The Chinese artists’ diaspora is returning to China. / 64 6 . Contemporary art museums in China are on the rise. / 74 7 . The world is collecting Chinese contemporary art. / 82 Conclusion / 90 Artist Biographies / 98 Further Reading / 110 Introduction 4 Sometimes it seems that scarcely a week goes by without a newspaper or magazine article on the Chinese contemporary art scene. Record-breaking auction prices make good headlines, but they also confer a value on the artworks that few of their makers would have dreamed possible when those works were originally created— sometimes only a few years ago, in other cases a few decades. It is easy to understand the artists’ surprise at their flourishing market and media success: the secondary auction market for Chinese contemporary art emerged only recently, in 2005, when for the first time Christie’s held a designated Asian Contemporary Art sale in its annual Asian art auctions in Hong Kong. The auctions were a success, including the modern and contemporary sales, which brought in $18 million of the $90 million total; auction benchmarks were set for contemporary artists Zhang Huan, Yan Pei-Ming, Yue Minjun, and many others. The following year, Sotheby’s held its first dedicated Asian Contemporary sale in New York.