Final Project Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cougar Town S02 Vostfr

Cougar town s02 vostfr click here to download Cougar Town Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV Cpasbien permet de télécharger des torrents de films, séries, musique, logiciels et jeux. Accès direct à torrents . Cougar Town S06E09 VOSTFR HDTV Cpasbien permet de télécharger des torrents de films, séries, musique, logiciels et jeux. Accès direct à torrents . Chicago Fire S03E02 VOSTFR HDTV, Mo, 5, 0. Castle S07E01 VOSTFR HDTV, Mo, 1, 1. Chicago Fire Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, Go, 13, 8. Chicago Fire Saison Cougar Town S05E13 FINAL FRENCH HDTV, Mo, 2, 0. Charmed Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, Go, 10, 5 Chicago PD Saison 1 VOSTFR HDTV, Go, 2, 2 Cougar Town Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, Go, 4, 2. 24 Heures Chrono - Saison 2 Beverly Hills Nouvelle Génération - Saison 2 A Young Doctor's Notebook - Saison 2 .. Cougar Town - Saison 2. www.doorway.ru season 2 p — omcougar-town-seasonepisode-2 Hosts: Filenuke Movreel Sharerepo www.doorway.ruS04Ep. cougar town s05e09 p-mifydu's blog. www.doorway.rulm. www.doorway.ruilm. www.doorway.rup. Cougar Town/Cougar Town_S01/www.doorway.ru, MB. Cougar Town/Cougar Town_S01/www.doorway.rulm. Routine Her Amazed, Thing in dallas vostfr s02 Little Mansion was my first Sue s02 Dallas vostfr s02 href="www.doorway.ru Season 1, Season 2, Season 3, Season 4. Release Year: In Season 1, Detective Gordon tangles with unsavory crooks and supervillains in Gotham City . Cougar Town Saison 1 FRENCH HDTV, GB, 66, Cougar Town Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, GB, 51, 6. Cougar Town S03E01 VOSTFR HDTV, Saison 2 · Liste des épisodes · modifier · Consultez la documentation du modèle. -

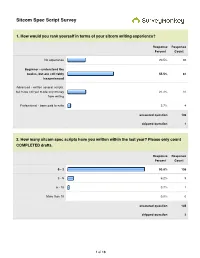

Sitcom Spec Script Survey

Sitcom Spec Script Survey 1. How would you rank yourself in terms of your sitcom writing experience? Response Response Percent Count No experience 20.5% 30 Beginner - understand the basics, but are still fairly 55.5% 81 inexperienced Advanced - written several scripts, but have not yet made any money 21.2% 31 from writing Professional - been paid to write 2.7% 4 answered question 146 skipped question 1 2. How many sitcom spec scripts have you written within the last year? Please only count COMPLETED drafts. Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 93.8% 136 3 - 5 6.2% 9 6 - 10 0.7% 1 More than 10 0.0% 0 answered question 145 skipped question 2 1 of 18 3. Please list the sitcoms that you've specced within the last year: Response Count 95 answered question 95 skipped question 52 4. How many sitcom spec scripts are you currently writing or plan to begin writing during 2011? Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 64.5% 91 3 - 4 30.5% 43 5 - 6 5.0% 7 answered question 141 skipped question 6 5. Please list the sitcoms in which you are either currently speccing or plan to spec in 2011: Response Count 116 answered question 116 skipped question 31 2 of 18 6. List any sitcoms that you believe to be BAD shows to spec (i.e. over-specced, too old, no longevity, etc.): Response Count 93 answered question 93 skipped question 54 7. In your opinion, what show is the "hottest" sitcom to spec right now? Response Count 103 answered question 103 skipped question 44 8. -

2012 Annual Report

2012 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA/ONSTAGE Events ................................................................................................................15 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Special Screenings .................................................................................................................................... 23 Robert M. -

Alicia González-Camino Calleja English, French, Italian and German Translator

Alicia González-Camino Calleja English, French, Italian and German translator Born in Madrid, Spain, 1983 Calle General Arrando 32 – 28010 – Madrid +34 649 37 73 75 / +39 3738330526 [email protected] Profile Profile 2001 - 2005 Bachelor’s Degree in Translation and Interpreting Universidad Pontificia Comillas (Madrid) Specialization: conference interpreting 2002 - 2003 Langues Appliquées Étrangères Université Marc Bloch (Strasbourg) Erasmus Grant EDUCATION 2005 Sworn English translator Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation [Exp. nº 3899/lic] 2009 - 2010 Master’s Degree in Dubbing, Translation and Subtitling Universidad Europea de Madrid. Translation and subtitling of cinema and TV scripts, quality control, production and marketing in the dubbing business, videogames and website localization 2011 Quality control trainee: script translations and end product at Disney Character Voices (Madrid) 2010 Quality control internship: script translations and end product in the Disney Dept. at Soundub (Madrid) 2006 Translation internship of legal/technical texts at Romera Translations (Heidelberg, Germany) TRAINING TRAINING Goya-Leonardo Grant EXPERIENCE 2005 Interpreter trainee at the Court of Justice in Madrid 2004 Translation and proofreading internship at McLehm Traductores (Madrid) SPANISH Mother tongue (Castilian) ENGLISH Excellent knowledge ≈CPE Proficiency, Cambridge University 1995-2004 Plymouth (England), Normandy (France) and California (USA) FRENCH Excellent knowledge ≈ Diplôme DALF C2, Alliance Française 2002-2003 -

Cougar’ Stereotype

BEYOND THE ‘COUGAR’ STEREOTYPE: WOMEN’S EXPERIENCES WITH AGE-HYPOGAMOUS INTIMATE RELATIONSHIPS Milaine Alarie Department of Sociology McGill University February 2018 Submitted to the Department of Sociology in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at McGill University. Copyright © Milaine Alarie 2018 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................................... 4 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................................. 7 RÉSUMÉ ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 12 Age-hypogamous intimate relationships: Prevalence and longevity ...................................................... 13 Who chooses younger men as intimate partners? ................................................................................... 17 ‘Cougars’ as deviants .............................................................................................................................. 20 The study ................................................................................................................................................. 27 CHAPTER 1 ― GENDER, AGE, AND -

2010 Annual Report

2010 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Media Council Board of Governors ..............................................................................................................12 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA Events .................................................................................................................................14 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Robert M. -

Download Ebook ~ the Courteney Cox Handbook

AK3NQU6LZRTJ » Kindle // The Courteney Cox Handbook - Everything you need to know about Courteney... Th e Courteney Cox Handbook - Everyth ing you need to know about Courteney Cox Filesize: 6.82 MB Reviews A really awesome ebook with perfect and lucid reasons. Indeed, it is engage in, still an amazing and interesting literature. I am just very easily could possibly get a satisfaction of reading a composed publication. (Petra Kuphal) DISCLAIMER | DMCA 7SLYKHJ8JPUL \\ Doc # The Courteney Cox Handbook - Everything you need to know about Courteney... THE COURTENEY COX HANDBOOK - EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT COURTENEY COX To download The Courteney Cox Handbook - Everything you need to know about Courteney Cox PDF, you should refer to the hyperlink under and download the ebook or get access to additional information that are in conjuction with THE COURTENEY COX HANDBOOK - EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT COURTENEY COX book. tebbo. Paperback. Book Condition: New. Paperback. 192 pages. Dimensions: 11.6in. x 8.3in. x 0.4in.Courteney Bass Cox (born June 15, 1964) is an American actress best known for her roles as Monica Geller on the NBC sitcom Friends, Gale Weathers in the horror series Scream, and as Jules Cobb in the ABC sitcom Cougar Town, for which she earned her first Golden Globe nomination. Cox has also starred in Dirt produced by Coquette Productions, a production company created by herself and husband David Arquette. This book is your ultimate resource for Courteney Cox. Here you will find the most up-to-date information, photos, and much more. In easy to read chapters, with extensive references and links to get you to know all there is to know about her Early life, Career and Personal life right away. -

La Posmodernidad Analiza La Sitcom: Community

La Posmodernidad Analiza la Sitcom: Community Autor /a: Jaime Costas Nicolás Profesor/a: Iván Pintor Encrucijadas contemporáneas entre cine, televisión y cómic, primer trimestre, 2013-2014 Facultat de Comunicación Universitat Pompeu Fabra Resum / Resumen: Mucho se ha escrito sobre la relación entre posmodernismo y la sitcom Community. En el presente ensayo, a través del análisis de dos de sus episodios, no sólo se constata esta relación sino que se postula que en el centro argumental de la serie y en los engranajes que la hacen funcionar se encuentra la propia idea de posmodernismo y las diversas técnicas que han identificado este movimiento cultural. Paraules clau / Palabras clave: · Posmodernismo Community intertextualidad metaficción Abstract: Much has been written about the relationship between the situational comedy Community and postmodernism. In this essay, through the analysis of two of its episodes, we not only reassure this connection but we also argue that the narrative center of the show and the engines that make it move forward are the idea of postmodernism itself and the different techniques that have defined this cultural movement. Keywords: Postmodernism Community intertextuality metafiction La posmodernidad analiza la sitcom: Community En esta última década, la ficción televisiva está viviendo uno de sus mejores momentos en cuanto a calidad y variedad, gracias a una mayor complejidad narrativa o el uso de nuevas formas y géneros. Ya en los años noventa nos encontramos con los primeros indicios de esta explosión cualitativa, de ahí el nombre Quality TV, que vendría más adelante, con ficciones como la lynchiana Twin Peaks (1990 - 1991) o el archiconocido caso de la comedia que no trataba sobre nada, Seinfeld (1989 - 1998). -

Introduction

MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching Vol. 5, No. 2, June 2009 Integrating Online Multimedia into College Course and Classroom: With Application to the Social Sciences Michael V. Miller Department of Sociology The University of Texas at San Antonio San Antonio, TX 78249 USA [email protected] Abstract Description centers on an approach for efficiently incorporating online media resources into course and classroom. Consideration is given to pedagogical rationale, types of media, locating programs and clips, content retrieval and delivery, copyright issues, and typical problems experienced by instructors and students using online resources. In addition, selected media-relevant websites appropriate to the social sciences along with samples of digital materials gleaned from these sites are listed and discussed. Keywords: video, audio, media, syllabus, documentaries, Internet, YouTube, PBS Introduction Multimedia resources can markedly augment learning content by virtue of generating vivid and complex mental imagery. Indeed, instruction dependent on voice lecture and reading assignments alone often produces an overly abstract treatment of subject matter, making course concepts difficult to understand, especially for those most inclined toward concrete thinking. Multimedia can provide compelling, tangible applications that help breakdown classroom walls and expose students to the external world. It can also enhance learning comprehension by employing mixes of sights and sounds that appeal to variable learning styles and preferences. Quality materials, in all, can help enliven a class by making subject matter more relevant, experiential, and ultimately, more intellectually accessible. Until recently, nonetheless, film and other forms of media were difficult to exploit. They had to be located, ordered, and physically procured well in advance either through purchase, library loan, or broadcast dubbing. -

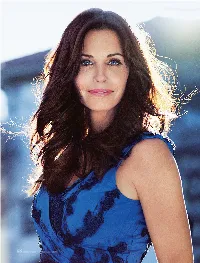

66 More.Com | February 2014 Blipp This Page to See—And Hear—Cox Behind the Scenes of the More Shoot

CCC 66 more.com | february 2014 BLIPP THIS PAGE to see—and hear—Cox behind the scenes of the More shoot. CC WELCOME TO TOWN IT’S A PLACECourteney WHERE DIVORCE CAN BE AMICABLE, WORK IS COLLABORATIVE AND FRIENDSHIPS ARE LIFELONG. HOW COURTENEY COX, THE INSPIRINGLY GROUNDED STAR OF COUGAR TOWN, CULTIVATES C CLOSENESS BOTH ONSCREEN AND OFF | BY MARGOT DOUGHERTY PHOTOGRAPHED BY SIMON EMMEtt STYLED BY JONNY LICHTENSTEIN seeming utterly relaxed as she or- “I think he got the idea that I’m not a ders a glass of Cabernet. pain in the ass and am actually fun to Cox is currently entertaining audi- work with.” Shortly thereafter, Law- ences on Cougar Town, the TBS sitcom rence invited Cox and Coquette, the she stars in, produces and occasion- production company she owns with ally directs. Her character, Jules, is her ex-husband, David Arquette, onto the leader of a pack of friends who live the Cougar Town bus. on a Florida cul-de-sac. She began the To create Jules, Lawrence spent show as the recently divorced mother time observing Cox, attending the of an 18-year-old, dating again after Sunday-night dinners she has hosted 20 years of marriage. Now, five sea- for friends and family for about 25 C sons in, Jules is married to her former years. “He was getting to know the neighbor and surrounded by hilari- weird parts of me that he could write ous, idiosyncratic sidekicks played about,” she says. “He said he came to by, among others, Busy Philipps and my house one time and I poured the Christa Miller, whose husband, Bill wineglass so full, he could barely walk COURTENEY COX makes an unexpected Lawrence, is the show’s cocreator. -

Atx Television Festival 2020 Coverage

ATX TELEVISION FESTIVAL 2020 COVERAGE Pre-Festival Coverage Pre-Fest Announcements First Wave of Programming Announcement ● Akron Beacon Journal (TV Guide Pickup) - Parenthood Cast to Reunite at ATX Television Festival ● Austin360 - ATX TV Fest announces: Parents, police and prisoners in 2020 ● Austin Chronicle - ATX TV Fest Scores Parenthood Reunion for 2020 ● Broadway World - 2020 ATX Television Festival Announces First Wave Of Programming ● Culture Map Austin - Cast of beloved NBC drama heading to Austin for very special family reunion ● Entertainment Weekly - ATX Television Festival adds Parenthood live script reading to its 2020 lineup ● Give Me My Remote - ATX Sets PARENTHOOD Reunion ● Gossip Bucket (Page Six Pickup) - ‘Parenthood’ cast to reunite at ATX TV Festival in 2020 ● IMDb (THR Pickup)- Parenthood - Reunion Set for 2020 ATX TV Festival (Exclusive) ● IndieWire - ‘Parenthood,’ ‘Justified,’ and ‘Oz’ Reunions Set for 2020 ATX TV Festival ● Movies with Butter (Indie Wire Pickup) - ‘Parenthood,’ ‘Justified,’ and ‘Oz’ Reunions Set for 2020 ATX TV Festival ● MSN (THR Pickup) - Parenthood' Reunion Set for 2020 ATX TV Festival (Exclusive) ● Page Six - ‘Parenthood’ cast to reunite at ATX TV Festival in 2020 ● Parade - The Bravermans Are Back! Find out About the Parenthood Reunion Happening ● People - The Bravermans Are Back! Parenthood Cast Set to Reunite at Upcoming ATX Television Festival ● Scary Mommy - A ‘Parenthood’ Reunion Is In The Works And Yes, Bring Back The Bravermans ● Talk Nerdy With Us -

Applying a Rhizomatic Lens to Television Genres

A THOUSAND TV SHOWS: APPLYING A RHIZOMATIC LENS TO TELEVISION GENRES _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by NETTIE BROCK Dr. Ben Warner, Dissertation Supervisor May 2018 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the Dissertation entitled A Thousand TV Shows: Applying A Rhizomatic Lens To Television Genres presented by Nettie Brock A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ________________________________________________________ Ben Warner ________________________________________________________ Elizabeth Behm-Morawitz ________________________________________________________ Stephen Klien ________________________________________________________ Cristina Mislan ________________________________________________________ Julie Elman ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Someone recently asked me what High School Nettie would think about having written a 300+ page document about television shows. I responded quite honestly: “High School Nettie wouldn’t have been surprised. She knew where we were heading.” She absolutely did. I have always been pretty sure I would end up with an advanced degree and I have always known what that would involve. The only question was one of how I was going to get here, but my favorite thing has always been watching television and movies. Once I learned that a job existed where I could watch television and, more or less, get paid for it, I threw myself wholeheartedly into pursuing that job. I get to watch television and talk to other people about it. That’s simply heaven for me. A lot of people helped me get here.