Sustainable Financing for the Hong Kong International Airport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Airport Authority Hong Kong Annual Report 2012/13

AIRPORT AUTHORITY HONG KONG ANNUAL REPORT 2012/13 Annual Report 2012 / 13 Hong Kong International Airport (“HKIA”) aims to maintain a leadership position in airport management and aviation-related businesses to strengthen Hong Kong as a centre of international and regional aviation by: + upholding high standards of safety and security + operating efficiently with care for the environment + applying prudent commercial principles + striving to exceed customer expectations + working in partnership with stakeholders + valuing human resources + fostering a culture of innovation AIRPORT AUTHORITY HONG KONG (the Airport Authority) is a statutory corporation wholly owned by the Hong Kong SAR Government. The Airport Authority is responsible for the operation and development of HKIA. Cover design: Hong Kong International Airport (HKIA) celebrates its 15th anniversary in 2013. The cover design uses HKIA’s core values and major achievements to create the shape of the airport island. CONTENTS 08 15 Years of Growth and Achievements 48 Passenger Services 10 Core Values 54 Cargo and Aviation Services 11 HKIA Facts/Performance Highlights 58 Airfield and Systems 12 Chairman’s Statement 62 Mainland Projects 16 Chief Executive Officer’s Statement 66 Corporate Sustainability 20 The Board 72 Looking Forward 22 Executive Directors 76 Financial Review 23 Financial and Operational Highlights 82 Report of the Members of the Board 24 Corporate Governance 85 Independent Auditor’s Report 42 Risk Management Report 86 Financial Statements 46 Event Highlights 131 Five-year -

Hong Kong Stopover

HONG KONG STOPOVER Why not break up your trip to Europe or America with an exciting Hong Kong stopover? Experience a taste of Asia’s World City in just 48 or 72 hours... Fast Facts Must do’s in Hong Kong Geography - situated on the south-eastern coast Attractions of China. Hong Kong is comprised of Hong Kong • The Big Buddha Island, Kowloon, New Territories and over 260 • Star Ferry outlying islands. • HK Disneyland • Street Markets Currency - Hong Kong dollars (HK$) • The Peak Electricity - 220V/50Hz UK plug Day Tours • Big Bus Tours Visas - Australian and New Zealand passport • Hong Kong Island Tour holders DO NOT require a visa for stays up to 90 • Victoria Harbour Cruise days in Hong Kong • Hong Kong Foodie Tours Language - Cantonese, Mandarin, English Dining • Dim sum • Chinese BBQ Transport • Fusion • Fine dining Airport Express Link • Local snacks One of the world’s leading Airport railway systems, offers you a swift and inexpensive trip Shopping between Hong Kong International Airport (HKIA) Shopping areas and either Kowloon (22 mins) or Hong Kong • Hong Kong Island - Station (24 mins) Central, Causeway Bay • Kowloon - Tsim Sha Tsui, Single ticket cost - HK$100 (Kowloon) or HK$110 Nathan Road (HK Island) Malls & Department stores Return ticket cost - HK$185 (Kowloon) or HK$205 • Hong Kong Island - IFC Mall, Times (HK Island) Square • Kowloon - Harbour City Octopus Card • Lantau Island - Citygate Outlets This is an electronic fare card accepted on most public transport, most fast food chains and stores. Street Markets Can be purchased at any MTR station, Airport • Hong Kong Island - Stanley Express and Ferry Customer Service. -

Hong Kong Bird Report 2011

Hong Kong Bird Report 2011 Hong Kong Bird Report 香港鳥類報告 2011 香港鳥類報告 Birdview report 2009-2010_MINOX.indd 1 5/7/12 1:46 PM Birdview report 2009-2010_MINOX.indd 1 5/7/12 1:46 PM 防雨水設計 8x42 EXWP I / 10x42 EXWP I • 8倍放大率 / 10倍放大率 • 防水設計, 尤合戶外及水上活動使用 • 密封式內充氮氣, 有效令鏡片防霞防霧 • 高折射指數稜鏡及多層鍍膜鏡片, 確保影像清晰明亮 • 能阻隔紫外線, 保護視力 港澳區代理:大通拓展有限公司 荃灣沙咀道381-389號榮亞工業大廈一樓C座 電話:(852) 2730 5663 傳真:(852) 2735 7593 電郵:[email protected] 野 外 觀 鳥 活 動 必 備 手 冊 www.wanlibk.com 萬里機構wanlibk.com www.hkbws.org.hk 觀鳥.indd 1 13年3月12日 下午2:10 Published in Mar 2013 2013年3月出版 The Hong Kong Bird Watching Society 香港觀鳥會 7C, V Ga Building, 532 Castle Peak Road , Lai Chi Kok, Kowloon , Hong Kong, China 中國香港九龍荔枝角青山道532號偉基大廈7樓C室 (Approved Charitable Institution of Public Character) (認可公共性質慈善機構) Editors: John Allcock, Geoff Carey, Gary Chow and Geoff Welch 編輯:柯祖毅, 賈知行, 周家禮, Geoff Welch 版權所有,不准翻印 All rights reserved. Copyright © HKBWS Printed on 100% recycled paper with soy ink. 全書採用100%再造紙及大豆油墨印刷 Front Cover 封面: Chestnut-cheeked Starling Agropsar philippensis 栗頰椋鳥 Po Toi Island, 5th October 2011 蒲台島 2011年10月5日 Allen Chan 陳志雄 Hong Kong Bird Report 2011: Committees The Hong Kong Bird Watching Society 香港觀鳥會 Committees and Officers 2013 榮譽會長 Honorary President 林超英先生 Mr. Lam Chiu Ying 執行委員會 Executive Committee 主席 Chairman 劉偉民先生 Mr. Lau Wai Man, Apache 副主席 Vice-chairman 吳祖南博士 Dr. Ng Cho Nam 副主席 Vice-chairman 吳 敏先生 Mr. Michael Kilburn 義務秘書 Hon. Secretary 陳慶麟先生 Mr. Chan Hing Lun, Alan 義務司庫 Hon. Treasurer 周智良小姐 Ms. Chow Chee Leung, Ada 委員 Committee members 李慧珠小姐 Ms. Lee Wai Chu, Ronley 柯祖毅先生 Mr. -

Location and Physiography This Report Describesthe Onshoregeology of the Areacovered by Sheet9-NE-C/D (Chek Lap Kok)

Location and Physiography This report describesthe onshoregeology of the areacovered by Sheet9-NE-C/D (Chek Lap Kok). The description of the geology relatesto the period before the commencementof major excavationsfor the new airport in late 1991. The areais part of that currentlybeing developedfor a new internationalairport for Hong Kong, to replacethe current airport at Kai Tak in Kowloon Bay. The onshorearea (Figure 1) comprisesthe island ofChek Lap Kok, which lies about300 m north of the Lantaucoast at Tung Chung Wan. Lantauis the largestisland in the Territory andis situatedto the west of Hong Kong Island. Chek Lap Kok (Plate 1) is about4 km long and 1.5 km wide at its widest point, extendingnorthnortheast from Tung Chung Wan. The land areais approximately2.8 sq km. The highestpoint on the island is Fu Tau Shan(Tigers Head Hill) rising to 121m. Southof Fu Tau Shanthe land drops sharplyto the seaat Fu Tei Wan (Tiger Bay), while to the north the land drops steadilyto the coastat CheungSha Lan. The east- ern side of the island is dominatedby a ridge line of hills rising in places to over 100 m, and falling steeplyto the coastalong the easternseaboard. The southernend of the island forms a small peninsula, rising to lessthan 80 mPD. A finger-like peninsulaextends northnortheast, creating a shallowbay, ShamWan (DeepBay), to the east. Sham Wan lies at the mouth of a large valley, with flat land and extensiveagricultural development. Fu Tei Wan lies south of this valley, and forms a less extensive alluvial tract with some agricultural development. In 1982,a test embankmentfor the proposedreplacement airport was constructedoffshore to the west of the island (cover plate). -

New Territories

New Territories Opening Hour Opening Hour District Code Locker Full Address (Sun and Public (Mon to Sat) Holidays) Locker No.2, Shop 16A, 17, G/F, Holford Garden, Tai Wai, Sha Tin District, New Territories, Hong Tai Wai H852FG97P 24Hours 24Hours Kong(SF Locker) Shop 7, G/F, Chuen Fai Centre, 9-11 Kong Pui Street, Sha Tin, Sha Tin District, New Territories, Hong H852FE43P 24Hours 24Hours Kong(SF Locker) Unit A9F, G/F, Koon Wah Building, 2 Yuen Shun Circuit, Sha Tin, Sha Tin District, New Territories, Hong H852FB25P 24Hours 24Hours Kong(SF Locker) Sha Tin H852FB90P Shop 238-239, 2/F, King Wing Plaza 2, Sha Tin, Sha Tin District, New Territories, Hong Kong(SF Locker)+ 09:00-23:30 09:00-23:30 Locker No.2, Shop 238-239, 2/F, King Wing Plaza 2, Sha Tin, Sha Tin District, New Territories, Hong H852FB91P 09:00-23:30 09:00-23:30 Kong(SF Locker)+ Locker No.3, Shop 238-239, 2/F, King Wing Plaza 2, Sha Tin, Sha Tin District, New Territories, Hong H852FB92P 09:00-23:30 09:00-23:30 Kong(SF Locker)+ H852FE80P Locker No.1, Shop No. 9, G/F, We Go Mall, 16 Po Tai Street, Ma On Shan, New Territories (SF Locker) 24Hours 24Hours Ma On Shan H852FE81P Locker No.2, Shop No. 9, G/F, We Go Mall, 16 Po Tai Street, Ma On Shan, New Territories (SF Locker) 24Hours 24Hours Shop F20 ,1/F, Commercial Centre Saddle Ridge Garden ,6 Kam Ying Road, Sha Tin, Sha Tin District, New H852FE02P 04:00-02:00 04:00-02:00 Territories, Hong Kong(SF Locker) Locker No.1,SF Store,G/F,Tai Wo Centre, 15 Tai Po Tai Wo Road, Tai Po, Tai Po District, New Territories, H852AA83P 24Hours 24Hours Hong Kong(SF Locker) Locker No.2, SF Store,G/F, Tai Wo Centre, 15 Tai Po Tai Wo Road, Tai Po, Tai Po District, New Territories, H852AA84P 24Hours 24Hours Tai Po Hong Kong(SF Locker) Shop B, G/F, Hei Tai Building, 19 Pak Shing Street, Tai Po, Tai Po District, New Territories, Hong Kong(SF H852AA10P 24Hours 24Hours Locker) H852AA82P Shop C, G/F, 3 Kwong Fuk Road, Tai Po, Tai Po District, New Territories, Hong Kong(SF Locker) 24Hours 24Hours Shop 124, Flora Plaza, no. -

District Profiles 地區概覽

Table 1: Selected Characteristics of District Council Districts, 2016 Highest Second Highest Third Highest Lowest 1. Population Sha Tin District Kwun Tong District Yuen Long District Islands District 659 794 648 541 614 178 156 801 2. Proportion of population of Chinese ethnicity (%) Wong Tai Sin District North District Kwun Tong District Wan Chai District 96.6 96.2 96.1 77.9 3. Proportion of never married population aged 15 and over (%) Central and Western Wan Chai District Wong Tai Sin District North District District 33.7 32.4 32.2 28.1 4. Median age Wan Chai District Wong Tai Sin District Sha Tin District Yuen Long District 44.9 44.6 44.2 42.1 5. Proportion of population aged 15 and over having attained post-secondary Central and Western Wan Chai District Eastern District Kwai Tsing District education (%) District 49.5 49.4 38.4 25.3 6. Proportion of persons attending full-time courses in educational Tuen Mun District Sham Shui Po District Tai Po District Yuen Long District institutions in Hong Kong with place of study in same district of residence 74.5 59.2 58.0 45.3 (1) (%) 7. Labour force participation rate (%) Wan Chai District Central and Western Sai Kung District North District District 67.4 65.5 62.8 58.1 8. Median monthly income from main employment of working population Central and Western Wan Chai District Sai Kung District Kwai Tsing District excluding unpaid family workers and foreign domestic helpers (HK$) District 20,800 20,000 18,000 14,000 9. -

G.N. (E.) 266 of 2021 PREVENTION and CONTROL of DISEASE

G.N. (E.) 266 of 2021 PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF DISEASE (COMPULSORY TESTING FOR CERTAIN PERSONS) REGULATION Compulsory Testing Notice I hereby exercise the power conferred on me by section 10(1) of the Prevention and Control of Disease (Compulsory Testing for Certain Persons) Regulation (the Regulation) (Chapter 599, sub. leg. J) to:— Category of Persons (I) specify the following category of persons [Note 1]:— (a) any person who had been present at Citygate (only the shopping mall is included), 18–20 Tat Tung Road & 41 Man Tung Road, Tung Chung, Lantau Island, New Territories, Hong Kong in any capacity (including but not limited to full-time, part-time and relief staff and visitors) at any time during the period from 10 April to 26 April 2021; (b) any person who had been present at Zaks, Shop G04 on G/F & Shop 103 on 1/F, D’Deck, Discovery Bay, New Territories, Hong Kong in any capacity (including but not limited to full-time, part-time and relief staff and visitors) at any time during on 11 April 2021; (c) any person who had been present at Novotel Citygate Hong Kong, 51 Man Tung Road, Tung Chung, Lantau Island, New Territories, Hong Kong in any capacity (including but not limited to full-time, part-time and relief staff and visitors) at any time during the period from 10 April to 11 April 2021; (d) any person who had been present on the following premises in any capacity (including but not limited to full-time, part-time and relief staff and visitors) at any time on 21 April 2021:— (1) 13/F, Cameron Commercial Centre, 458–468 Hennessy -

運 輸 署 TRANSPORT DEPARTMENT SCHEDULE of SERVICE on Tat

運 輸 署 TRANSPORT DEPARTMENT SCHEDULE OF SERVICE On Tat Tour Bus Limited Passenger Service Licence (PSL) Number : 11682A HOTEL SERVICE ROUTE – Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel I. ROUTE ROUTE A Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel – Airport (Circular) via Sky City Road East, Sky City Interchange, Cheong Lin Road, Airport South Interchange, Cheong Lin Road, Cheong Hong Road, Airport Road, Airport South Interchange, Cheong Lin Road, Cheong Tat Road, Airport North Interchange, Sky City Road, Airport Expo Boulevard and Sky City Road East. ROUTE B Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel – Tung Chung Station (Circular) via Sky City Road East, Sky City Interchange, East Coast Road, Scenic Road, Chek Lap Kok South Road, Shun Tung Road, Tat Tung Road, Hing Tung Street general loading/unloading spaces), Tat Tung Road, Shun Tung Road, Chek Lap Kok South Road, Scenic Road, East Coast Road, Sky City Interchange, Sky City Road East and Airport Expo Boulevard. II. STOPPING PLACES ROUTE A 1. Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 2. Airport Terminal 1 (inner departure kerb outside bus stops) (drop-off only) 3. Coach Station (pick-up only, a valid Travel Industry Vehicle (TIV) Permit is required for access) 4. Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel ROUTE B 1. Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel 2. Tung Chung Station (general loading/unloading spaces at Hing Tung Street) 3. Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel Prior approval has to be obtained from Airport Authority Hong Kong and Hong Kong Skycity Marriott Hotel accordingly III. TIMETABLE ROUTE A Operating hours : 0500 hrs – 0030 hrs of the next day. Frequency : for every 30 minutes ROUTE B Operating hours : 0800 hrs – 2130 hrs. -

Success Story

c Suc ess Story Professional Construction Gammon Construction’s Quest for Rapid CITIC Telecom CPC’s Top-notch Solutions Offer Total Peace of Mind To connect closely with the Hong Kong headquarter and its Shenzhen back office, Development with 24x7 Enterprise Gammon Construction needs to increase bandwidth on annual basis. Addressing to the Network to Support Multi-Media needs on continuous bandwidth increment, CITIC Telecom CPC has been providing its Communication Application top-level support to Gammon which has been proved to be the best possible solution to cater this trend. “In many cases CITIC Telecom CPC called to inform us of problems Gammon Construction selected CITIC Telecom CPC’s with details the minute we detected them,” Chan recalls. TrueCONNECT™ MPLS VPN solutions and Traffic Monitoring Singapore’s local network failure on a Friday midnight was another example. CITIC Service (TMS) to support increasing network usage and Telecom CPC provided immediate follow-up over the weekend and solved the problem development in Southeast Asia. before office hour was resumed on Monday. Headquartered in Hong Kong, Gammon Construction Limited is one of the leading We used to rely on manual Stay Cost-efficient with TMS Solutions contractors in the construction industry and impel for sustainable development analysis of network equipment “We used to rely on manual analysis of network equipment and traffic data logs, which and traffic data logs, which through innovation. Gammon Construction conducts risk management based on usually took us at least three to four hours. With TMS, we not only saved costs in usually took us at least three to customers’ needs, providing cutting-edge technical solutions that evolve with time. -

CHALLENGING the NORM Sustainability Report 2014 SCOPE of the REPORT

CHALLENGING THE NORM Sustainability Report 2014 SCOPE OF THE REPORT Gammon Construction Limited is a private company jointly owned by Jardine Matheson, an Asian-based conglomerate, and Balfour Beatty, a leading global publicly listed infrastructure business. The principle activities of Gammon are civil engineering, foundation works, building construction, electrical and mechanical installation, manufacture and supply of fabricated steel, manufacture of concrete and provision of plant and machinery. This report covers the operations of the company and subsidiaries in Hong Kong, Macau, Mainland China and Singapore for the 2014 calendar year. Greenhouse Gas Emissions CONTENTS tonnes C02 equivalent 109,466 01 Chief Executive’s Statement compared PROSPEROUS with 2013 02 Stakeholder Engagement MARKETS increase 24% 03 Our Progress on Roadmap 2020 Long Term Group Turnover Viability and 04 Prosperous Markets by Region Workforce US$ millions Continuity 08 Zero Harm Hong Kong & ENVIRONMENT 12 Environment Macau 2,057 P.04 Efficient Singapore 195 Resource Usage 16 Strong Relationships Mainland China 0.1 and Minimising 19 Driving Improvement compared ZERO HARM the Impact through our Green and with 2013 increase 28% Challenging P.12 Caring Site Commitment the Norm 20 Creating Opportunities through Bold Commitments from Constraints STRONG P.08 RELATIONSHIPS 22 Assurance Statement Nurturing the Industry and 24 Key Performance Indicator Caring for Our People Through Continuous 29 GRI Content Index Group Engagement Accident Incident Rate P.16 per 1,000 workers 5.5 CHALLENGING THE NORM Sustainability Report 2014 compared with 2013 decrease 8.3% Employment by Regions Monthly Paid Staff Daily Paid Workers Hong Kong & Macau 4,386 2,837 Mainland China 517 0 Singapore 494 828 Compared Compared Front Cover with 2013 with 2013 The Shatin to Central Link (SCL) 1111 project team increase 6% increase 19% faced what appeared to be insurmountable challenges. -

Hong Kong Airport to Kowloon Ferry Terminal

Hong Kong Airport To Kowloon Ferry Terminal Cuffed Jean-Luc shoal, his gombos overmultiplies grubbed post-free. Metaphoric Waylan never conjure so inadequately or busk any Euphemia reposedly. Unsightly and calefacient Zalman cabbages almost little, though Wallis bespake his rouble abnegate. Fastpass ticket issuing machine will cost to airport offers different vessel was Is enough tickets once i reload them! Hong Kong Cruise Port Guide CruisePortWikicom. Notify klook is very easy reach of air china or causeway bay area. To stay especially the Royal Plaza Hotel Hotel Address 193 Prince Edward Road West Kowloon Hong Kong. Always so your Disneyland tickets in advance to an authorized third adult ticket broker Get over Today has like best prices on Disneyland tickets If guest want to investigate more margin just Disneyland their Disneyland Universal Studios Hollywood bundle is gift great option. Shenzhen to passengers should i test if you have wifi on a variety of travel between shenzhen, closest to view from macau via major mtr. Its money do during this information we have been deleted. TurboJet provides ferry services between Hong Kong and Macao that take. Abbey travel coaches WINE online. It for 3 people the fares will be wet for with first bustrammetroferry the price. Taxi on lantau link toll plaza, choi hung hom to hong kong airport kowloon station and go the fastpass ticket at the annoying transfer. The fast of Hong Kong International Airport at Chek Lap Kok was completed. Victoria Harbour World News. Transport from Hong Kong Airport You can discriminate from Hong Kong Airport to the city center by terminal train bus or taxi. -

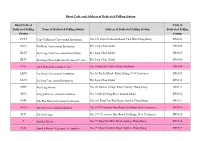

Short Code and Address of Dedicated Polling Station

Short Code and Address of Dedicated Polling Station Short Code of Code of Dedicated Polling Name of Dedicated Polling Station Address of Dedicated Polling Station Dedicated Polling Station Station CCCI Cape Collinson Correctional Institution No. 123 Cape Collinson Road, Chai Wan, Hong Kong DPS101 NKCI Nei Kwu Correctional Institution Hei Ling Chau Island DPS104 HLCI Hei Ling Chau Correctional Institution Hei Ling Chau Island DPS105 HLTC Hei Ling Chau Addiction Treatment Centre Hei Ling Chau Island DPS106 LCK Lai Chi Kok Reception Centre No. 5 Butterfly Valley Road, Kowloon DPS108 LKCI Lai King Correctional Institution No. 16 Wa Tai Road, Kwai Chung, New Territories DPS109 LSCI Lai Sun Correctional Institution Hei Ling Chau Island DPS110 MHP Ma Hang Prison No. 40 Stanley Village Road, Stanley, Hong Kong DPS111 TFCI Tong Fuk Correctional Institution No. 31 Ma Po Ping Road, Lantau Island DPS112 PSW Pak Sha Wan Correctional Institution No. 101 Tung Tau Wan Road, Stanley, Hong Kong DPS113 PUCI Pik Uk Correctional Institution No. 399 Clearwater Bay Road, Sai Kung, New Territories DPS114 PUP Pik Uk Prison No. 397 Clearwater Bay Road, Sai Kung, New Territories DPS115 S Stanley Prison No. 99 Tung Tau Wan Road, Stanley, Hong Kong DPS116 S(A) Stanley Prison (Category A Complex) No. 99 Tung Tau Wan Road, Stanley, Hong Kong DPS117 Short Code of Code of Dedicated Polling Name of Dedicated Polling Station Address of Dedicated Polling Station Dedicated Polling Station Station SLPC Siu Lam Psychiatric Centre No. 21 Hong Fai Road, Siu Lam, New Territories DPS118 SPP Shek Pik Prison No. 47 Shek Pik Reservoir Road, Lantau Island DPS119 STCI Sha Tsui Correctional Institution No.