ONE and DONE One and Done: Examining the Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019-2021 NCAA WOMEN's BASKETBALL GAME ADMINISTRATION and TABLE CREW REFERENCE SHEET GAME ADMINISTRATION Game Administration

2019-2021 NCAA WOMEN’S BASKETBALL GAME ADMINISTRATION AND TABLE CREW REFERENCE SHEET Edited by Jon M. Levinson, Women’s Basketball Secretary-Rules Editor [email protected] GAME ADMINISTRATION Game administration shall make available an individual at each basket with a device capable of untangling the net when necessary. The individual must ensure that play has clearly moved away from the affected basket before going onto the playing court. SCORER It is strongly recommended that the scorer be present at the table with no less than 15 minutes remaining on the pregame clock. Signals 1. For a team’s fifth foul, the scorer will display two fingers and verbally state the team is in the bonus. The public- address announcer is not to announce the number of team fouls beyond the fifth team foul. 2. in a game with replay equipment, record the time on the game clock when the official signals for reviewing a two- or three-point goal. 3. For a disqualified player, the scorer will inform the officials as soon as possible by displaying five fingers with an open hand and verbally state that this is the fifth foul on the number of the disqualified player. New Rules 1. During two- or three-shot free throw situations, substitutes are permitted before the first attempt or when the last attempt is successful. 2. A replaced player may reenter the game before the game clock has properly started and stopped when the opposing team has committed a foul or violation. GAME CLOCK TIMER TIMER must: 1. Confirm with the officials that the game clock is operating properly, which includes displaying tenths-of-a-second under one minute, the horn is operating, and the red/LED lights are functioning. -

2020-09-Basketball-Officials-Test

RULE TEST 1 Q1 - A5 is fouled and is awarded 2 free throws. After the first, the officials discover that B4 is bleeding. B4 is replaced by B7. Team A is entitled to substitute only 1 player. TRUE. Q2 - A3 passes the ball from the 3 point area. When the ball is above the ring, B1 reaches through the basket from below and touches the ball. This is an interference violation and 2 poiints shall be awarded to Team A. FALSE. Q3 - A2 attempts a shot for a field goal with 20 seconds on the shot clock. The ball touches the ring, rebounds and A1 gains control of the ball in Team A backcourt. The shot clock shall show 14 seconds as soon as A1 gains control of the ball. TRUE Q4 - During a pass by A4 to A5, the ball touches B1 after which the ball touches the ring. Then, A1 gains control of the ball. The shot clock shall show 14 seconds as soon as the ball touches the ring. FALSE. Q5 - A3 attempts a successful shot for a 3-points field goal and approximately at the same time, the game clock signal sounds for the end of the quarter. The officials are not sure if A1 has touched the boundary line on his shot. The IRS can be reviewed to decide if the out-of-bounds violation occurred and, in such a case, how much time shall be shown on the game clock. TRUE. Q6 - A2 in the act of shooting is fouled simultaneously with the game clock signal for the end of the first quarter. -

Optimizing End of Quarter Shot-Timing in the NBA: "Everyone Knows About the 2 for 1, but What About the 3 for 2?"

Optimizing End Of Quarter Shot-Timing In The NBA: "Everyone Knows About The 2 For 1, But What About The 3 For 2?" Jesse Fischer B.S. Computer Engineering, University of Washington Senior Software Engineer, Amazon.com [email protected] www.tothemean.com Abstract Since the advent of the shot clock, the "2-for-1" has become a common end of quarter strategy in the NBA. With this approach, a team will strategically time their shot in hopes of ensuring a second possession while limiting their opponent to a single possession. Prior research has shown the effectiveness of the "2-for-1" strategy but no well-known public study has explored extending this strategy to "3-for-2" or beyond. This paper summarizes a study which: (1) analyzes the effects that possession timing has on behavior as well as outcome; (2) quantifies the cost-benefit tradeoff of strategically "timing a possession;" and (3) proposes the optimal possession timing strategy to maximize expected points (as opposed to simply possessions). The research reveals how to improve end of quarter behavior in the NBA by better understanding the math behind why, and when, a "2-for-1" is beneficial and suggests how to extend this further to a "3-for-2". Introduction The average value of a possession in the NBA is estimated at just over 1 point [1]. If a team is able to capture an extra possession in only half of those quarters, this could mean the difference between a team winning a game and potentially making the playoffs. The 2013-2014 Phoenix Suns are an example of a team where extra possessions could have made a big difference. -

2019-20 Panini Flawless Basketball Checklist

2019-20 Flawless Basketball Player Card Totals 281 Players with Cards; Hits = Auto+Auto Relic+Relic Only **Totals do not include 2018/19 Extra Autographs TOTAL TOTAL Auto Relic Block Team Auto HITS CARDS Relic Only Chain A.C. Green 177 177 177 Aaron Gordon 141 141 141 Aaron Holiday 112 112 112 Admiral Schofield 77 77 77 Adrian Dantley 115 115 59 56 Al Horford 385 386 177 169 39 1 Alex English 177 177 177 Allan Houston 236 236 236 Allen Iverson 332 387 295 1 36 55 Allonzo Trier 286 286 118 168 Alonzo Mourning 60 60 60 Alvan Adams 177 177 177 Andre Drummond 90 90 90 Andrea Bargnani 177 177 177 Andrew Wiggins 484 485 118 225 141 1 Anfernee Hardaway 9 9 9 Anthony Davis 453 610 118 284 51 157 Arvydas Sabonis 59 59 59 Avery Bradley 118 118 118 B.J. Armstrong 177 177 177 Bam Adebayo 92 92 92 Ben Simmons 103 132 103 29 Bill Bradley 9 9 9 Bill Russell 186 213 177 9 27 Bill Walton 59 59 59 Blake Griffin 90 90 90 Bob McAdoo 177 177 177 Bobby Portis 118 118 118 Bogdan Bogdanovic 230 230 118 112 Bojan Bogdanovic 90 90 90 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2019-20 Flawless Basketball Player Card Totals TOTAL TOTAL Auto Relic Block Team Auto HITS CARDS Relic Only Chain Bradley Beal 93 95 93 2 Brandon Clarke 324 434 59 226 39 110 Brandon Ingram 39 39 39 Brook Lopez 286 286 118 168 Buddy Hield 90 90 90 Calvin Murphy 236 236 236 Cam Reddish 380 537 59 228 93 157 Cameron Johnson 290 291 225 65 1 Carmelo Anthony 39 39 39 Caron Butler 1 2 1 1 Charles Barkley 493 657 236 170 87 164 Charles Oakley 177 177 177 Chauncey Billups 177 177 177 Chris Bosh 1 2 1 1 Chris Kaman -

24 SECOND CLOCK Once a Team Gains Control of the Basketball, That

24 SECOND CLOCK Once a team gains control of the basketball, that team has 24 seconds to put up a legal shot. A legal shot is defined as a shot that is successful, or if unsuccessful, hits the ring. That shot has to be in the air (left the shooters hand) , before 24 secs has elapsed. So if the clock sounds after the shot is in the air, and that shot is successful, or hits the ring, that is NOT a violation. The shot clock starts when a team gains procession of the ball, and can re set when procession changes, a violation occurs, a foul occurs, a jump ball, or a legal shot hits the ring. The 24 second clock operates on team procession. Team A has procession, until Team B gains procession. So if Team A has control of the ball, then a player from team B happens to tap it, but not gain control, then Team A is in still in control. Basically it is mine until it is yours A player, therefore a team, is in control of the ball when they have it in 2 hands, or they are in a position to dribble the ball. So a player who jumps in the air and flings the ball back into court is not in control of the ball. At the beginning of a game, the game clock starts when the ball is legally tapped by a player. The shot clock does not start until a player has gained control of the ball. Once a player has gained control, his team has 24 seconds to get a shot off. -

Middle of the Pack Biggest Busts Too Soon to Tell Best

ZSW [C M Y K]CC4 Tuesday, Jun. 23, 2015 ZSW [C M Y K] 4 Tuesday, Jun. 23, 2015 C4 • SPORTS • STAR TRIBUNE • TUESDAY, JUNE 23, 2015 TUESDAY, JUNE 23, 2015 • STAR TRIBUNE • SPORTS • C5 2015 NBA DRAFT HISTORY BEST OF THE REST OF FIRSTS The NBA has held 30 drafts since the lottery began in 1985. With the Wolves slated to pick first for the first time Thursday, staff writer Kent Yo ungblood looks at how well the past 30 N o. 1s fared. Yo u might be surprised how rarely the first player taken turned out to be the best player. MIDDLE OF THE PACK BEST OF ALL 1985 • KNICKS 1987 • SPURS 1992 • MAGIC 1993 • MAGIC 1986 • CAVALIERS 1988 • CLIPPERS 2003 • CAVALIERS Patrick Ewing David Robinson Shaquille O’Neal Chris Webber Brad Daugherty Danny Manning LeBron James Center • Georgetown Center • Navy Center • Louisiana State Forward • Michigan Center • North Carolina Forward • Kansas Forward • St. Vincent-St. Mary Career: Averaged 21.0 points and 9.8 Career: Spurs had to wait two years Career: Sixth all-time in scoring, O’Neal Career: ROY and a five-time All-Star, High School, Akron, Ohio Career: Averaged 19 points and 9 .5 Career: Averaged 14.0 pts and 5.2 rebounds over a 17-year Hall of Fame for Robinson, who came back from woN four titles, was ROY, a 15-time Webber averaged 20.7 points and 9.8 rebounds in eight seasons. A five- rebounds in a career hampered by Career: Rookie of the Year, an All- career. R OY. -

Donruss Basketball 2015-16 Nba Trading Cards

PANINI AMERICA, INC. DONRUSS BASKETBALL 2015-16 NBA TRADING CARDS © 2016 Panini America, Inc. © 2016 NBA Properties, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Printed in the USA. All information is accurate at the time of posting – content is subject to change. Card images are solely for the purpose of design display. Actual images used on cards to be determined. DONRUSS BASKETBALL 2015-16 NBA TRADING CARDS RATED ROOKIES BASE RATED ROOKIES KARL-ANTHONY TOWNS KOBE BRYANT KRISTAPS PORZINGIS Featuring the throwback style that defines the brand, Donruss showcases beautiful open photography and stunning action throughout. © 2016 Panini America, Inc. © 2016 NBA Properties, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Printed in the USA. All information is accurate at the time of posting – content is subject to change. Card images are solely for the purpose of design display. Actual images used on cards to be determined. DONRUSS BASKETBALL 2015-16 NBA TRADING CARDS ELITE DOMINATOR ELITE ROOKIE DOMINATOR ELITE DOMINATOR SIGNATURES KYRIE IRVING JAHLIL OKAFOR KEVIN DURANT Look for stunning Hobby-exclusive Elite Dominator cards that feature the NBA’s top stars and most promising prospects! Find the rare Signatures version, sequentially numbered to 25. © 2016 Panini America, Inc. © 2016 NBA Properties, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Printed in the USA. All information is accurate at the time of posting – content is subject to change. Card images are solely for the purpose of design display. Actual images used on cards to be determined. DONRUSS BASKETBALL 2015-16 NBA TRADING CARDS ROOKIE MATERIAL SIGNATURES PRIME TIMELESS TREASURES AUTO MAT PRIME RATED ROOKIE SIGNATURE PATCHES D’ANGELO RUSSELL JOHN WALL EMMANUEL MUDIAY Chase autographs and memorabilia from the NBA’s best and brightest, from seasoned veterans to fresh-faced rookies. -

Shooting Guard Day 9:00-10:00: Warmups ● 9:00-9:15: Stretch/Roll Call O Spread the Children out Across the Court

Day 2: Shooting Guard Day 9:00-10:00: Warmups ● 9:00-9:15: Stretch/Roll Call o Spread the children out across the court. 8 lines. ● 9:15-9:30: Explain the camp o Introduce coaches, curriculum, and schedule ● 9:30-9:45: Form six lines on the baseline. o Regular: Running, Back pedal, high knee, power skip, karaoke, defense slide, Frankenstein, lunges, bear-crawl ● 9:45-10:00: Ball Warm-up o Right hand, left hand, V dribble, backpedal dribble 10:00-11:00: Drill Stations ● Drill Station 1: V-Cut/L-Cut/backdoor o The coach will stand at the top of the 3-point line to start. Two lines will form on both wings of the 3-point line. Players from each line will take turns cutting for the ball. Once the cut is complete, the coach will pass to the player for a spot-up shot or lay-up. Emphasize agility and quick changes of direction. ● Drill Station 2: Help defense (One pass away) o 3 offensive players will line up around the 3-point line, within passing distance. 2 players will stand between them in defensive stance. The offensive players will pass to one-another around the perimeter. The defensive players will practice switching and help defense. Emphasize the fundamentals of 1 or 2 passes away. ● Drill Station 3: Elbow to elbow shot challenge o Set up two cones at each end of the free-throw line. The coach will stand under the basket, while the player begins at either cone. The drill begins when the coach passes to the player. -

2012-13 BOSTON CELTICS Media Guide

2012-13 BOSTON CELTICS SEASON SCHEDULE HOME AWAY NOVEMBER FEBRUARY Su MTWThFSa Su MTWThFSa OCT. 30 31 NOV. 1 2 3 1 2 MIA MIL WAS ORL MEM 8:00 7:30 7:00 7:30 7:30 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 WAS PHI MIL LAC MEM MEM TOR LAL MEM MEM 7:30 7:30 8:30 1:00 7:30 7:30 7:00 8:00 7:30 7:30 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 CHI UTA BRK TOR DEN CHA MEM CHI MEM MEM MEM 8:00 7:30 8:00 12:30 6:00 7:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 DET SAN OKC MEM MEM DEN LAL MEM PHO MEM 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:AL30L-STAR 7:30 9:00 10:30 7:30 9:00 7:30 25 26 27 28 29 30 24 25 26 27 28 ORL BRK POR POR UTA MEM MEM MEM 6:00 7:30 7:30 9:00 9:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 DECEMBER MARCH Su MTWThFSa Su MTWThFSa 1 1 2 MIL GSW MEM 8:30 7:30 7:30 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 MEM MEM MEM MIN MEM PHI PHI MEM MEM PHI IND MEM ATL MEM 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:00 7:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 MEM MEM MEM DAL MEM HOU SAN OKC MEM CHA TOR MEM MEM CHA 7:30 7:30 7:30 8:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 1:00 7:30 7:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 MEM MEM CHI CLE MEM MIL MEM MEM MIA MEM NOH MEM DAL MEM 7:30 7:30 8:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 8:00 7:30 8:00 7:30 8:30 8:00 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 MEM MEM BRK MEM LAC MEM GSW MEM MEM NYK CLE MEM ATL MEM 7:30 7:30 12:00 7:30 10:30 7:30 10:30 7:30 7:30 7:00 7:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 30 31 31 SAC MEM NYK 9:00 7:30 7:30 JANUARY APRIL Su MTWThFSa Su MTWThFSa 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 MEM MEM MEM IND ATL MIN MEM DET MEM CLE MEM 7:30 7:30 7:30 8:00 -

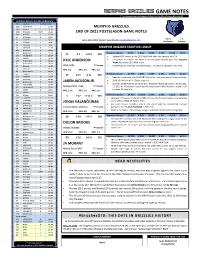

GAME NOTES for In-Game Notes and Updates, Follow Grizzlies PR on Twitter @Grizzliespr

GAME NOTES For in-game notes and updates, follow Grizzlies PR on Twitter @GrizzliesPR GRIZZLIES 2020-21 SCHEDULE/RESULTS Date Opponent Tip-Off/TV • Result 12/23 SAN ANTONIO L 119-131 MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES 12/26 ATLANTA L 112-122 12/28 @ Brooklyn W (OT) 116-111 END OF 2021 POSTSEASON GAME NOTES 12/30 @ Boston L 107-126 1/1 @ Charlotte W 108-93 38-34 1-4 1/3 LA LAKERS L 94-108 Game Notes/Stats Contact: Ross Wooden [email protected] Reg Season Playoffs 1/5 LA LAKERS L 92-94 1/7 CLEVELAND L 90-94 1/8 BROOKLYN W 115-110 MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES STARTING LINEUP 1/11 @ Cleveland W 101-91 1/13 @ Minnesota W 118-107 SF # 1 6-8 ¼ 230 Previous Game 4 PTS 2 REB 5 AST 2 STL 0 BLK 24:11 1/16 PHILADELPHIA W 106-104 Selected 30th overall in the 2015 NBA Draft after two seasons at UCLA. 1/18 PHOENIX W 108-104 First player to compile 10+ steals in any two-game playoff span since Dwyane 1/30 @ San Antonio W 129-112 KYLE ANDERSON 2/1 @ San Antonio W 133-102 Wade during the 2013 NBA Finals. th 2/2 @ Indiana L 116-134 UCLA / USA 7 Season Career-high 94 3PM this season (previous: 24 3PM in 67 games in 2019-20). 2/4 HOUSTON L 103-115 PPG: 8.4 RPG: 5.0 APG: 3.2 2/6 @ New Orleans L 109-118 2/8 TORONTO L 113-128 PF # 13 6-11 242 Previous Game 21 PTS 6 REB 1 AST 1 STL 0 BLK 26:01 2/10 CHARLOTTE W 130-114 Selected fourth overall in 2018 NBA Draft after freshman year at Michigan State. -

Illegal Defense: the Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce Law Faculty Scholarship School of Law 1-1-2004 Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft Michael McCann University of New Hampshire School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/law_facpub Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Collective Bargaining Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, Sports Management Commons, Sports Studies Commons, Strategic Management Policy Commons, and the Unions Commons Recommended Citation Michael McCann, "Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft," 3 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L. J.113 (2004). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 3 Va. Sports & Ent. L.J. 113 2003-2004 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Mon Aug 10 13:54:45 2015 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=1556-9799 Article Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft Michael A. -

34 Paul Pierce #32 Blake Griffin #6 Deandre

Los Angeles Clippers (1-0) at Toronto Raptors (0-0) Game P2| Away Game 1 Rogers Arena; Vancouver, BC Sunday, October 4, 2015 - 4:00 p.m. (PDT) TV: Prime Ticket; Radio: The Beast 980 AM/1330 AM KWKW PRESEASON CLIPPERS PROBABLE STARTERS DATE OPPONENT TELEVISION RESULT/TIME Oct. 2 vs. Denver Prime Ticket W, 103-96 Oct. 4 at Toronto* Prime Ticket 4:00 PM #34 PAUL PIERCE Oct. 10 at Charlotte** NBA TV 10:30 PM Oct. 14 vs. Chatlotte*** NBA TV 5:00 AM F • 6-7 • 235 Oct. 20 vs. Golden State ESPN 7:30 PM Oct. 22 vs. Portland Prime Ticket 7:30 PM 2015-16 Preseason Stats *Game will be played in Vancouver, British Columbia **Game will be played in Shenzhen, China MIN PTS REB AST FG% ***Game will be played in Shanghai, China 14.0 5.0 1.0 1.0 .250 REGULAR SEASON LAST GAME: 10/2 vs. DEN, had 5 pts (1-4 FG, 1-2 3PT, 2-2 FT), 1 reb, 1 ast and 2 stls in 14:16 minutes. DATE OPPONENT TELEVISION RESULT/TIME 2014-15 PLAYER NOTES: Posted five games of 20+ points…Led Washington with 118 made three-pointers... Oct. 28 at Sacramento Prime Ticket 7:00 PM Oct. 29 vs. Dallas TNT 7:30 PM On 11/25/14, surpassed Jerry West for 17th all-time in points scored…On 12/8/14 vs. BOS, scored a season- Oct. 31 vs. Sacramento Prime Ticket/NBA TV 7:30 PM high 28 points & surpassed Reggie Miller for 16th all-time in points scored...Became the 4th player in NBA history Nov.