Postmodern and Existential Ethics in Paul Auster's Moon Palace and Leviathan Dominic John D'urso Iowa State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 289 5th International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Inter-cultural Communication (ICELAIC 2018) A Review of Paul Auster Studies* Long Shi Qingwei Zhu College of Foreign Language College of Foreign Language Pingdingshan University Pingdingshan University Pingdingshan, China Pingdingshan, China Abstract—Paul Benjamin Auster is a famous contemporary Médaille Grand Vermeil de la Ville de Paris in 2010, American writer. His works have won recognition from all IMPAC Award Longlist for Man in the Dark in 2010, over the world. So far, the Critical Community contributes IMPAC Award long list for Invisible in 2011, IMPAC different criticism to his works from varied perspectives in the Award long list for Sunset Park in 2012, NYC Literary West and China. This paper tries to make a review of Paul Honors for Fiction in 2012. Auster studies, pointing out the achievement which has been made and others need to be made. II. A REVIEW OF PAUL AUSTER‘S LITERARY CREATION Keywords—a review; Paul Auster; studies In 1982, Paul Auster published The Invention of Solitude which reflected a literary mind that was to be reckoned with. I. INTRODUCTION It consists of two sections. Portrait of an Invisible Man, the first part, is mainly about his childhood in which there is an Paul Benjamin Auster (born February 3, 1947) is a absence of fatherly love and care. His memory of his growth talented contemporary American writer with great is full of lack of fatherly attention: ―for the first years of my abundance of voluminous works. -

An Analysis Of" City of Glass" by Paul Auster in Terms of Postmodernism

International Journal of Languages’ Education and Teaching Volume 5, Issue 1, April 2017, p. 478-486 Received Reviewed Published Doi Number 17.01.2017 16.02.2017 24.04.2017 10.18298/ijlet.1659 AN ANALYSIS OF CITY OF GLASS BY PAUL AUSTER FROM A POSTMODERNIST PERSPECTIVE1 Mehmet Cem ODACIOĞLU 2 & Chek Kim LOI3 & Fadime ÇOBAN4 ABSTRACT This study analyzes City of Glass, a postmodernist detective novella (or anti-detective) of the New York Trilogy by Paul Auster in terms of postmodernist elements and techniques such as metafiction, parody, intertextuality, irony. In doing so, some information about Auster’s life and the plot of the work are also offered to the reader to make the analysis more concrete. Last but not least, this study is also thought to be useful for students enrolled in English Language and Literary Departments for them to understand the movement of postmodernism. Key Words: City of Class, postmodernist detective fiction, anti-detective, metafiction, parody, irony, intertextuality, pastiche. 1.Short Biography of Paul Auster Paul Auster is an American-Jewish essayist, novelist, translator, poet, screenwriter and memoirist, who was born in Newark, New Jersey on February 3, 1947. Auster lived in a middle class family and spent some of his childhood in the Newark suburbs of South Orange and Maplewood. However, in 1959, his family moved into a large Tudor house. Auster's uncle, Allen Mandelbaum was a translator and left his books for him to read there when he decided to make a journey to Europe. Auster read all of these books which encouraged him to be interested in writing and in literature. -

Wireless Power Transmission

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 10, October-2014 125 ISSN 2229-5518 Wireless Power Transmission Mystica Augustine Michael Duke Final year student, Mechanical Engineering, CEG, Anna university, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India [email protected] ABSTRACT- The technology for wireless power transfer (WPT) is a varied and a complex process. The demand for electricity is much higher than the amount being produced. Generally, the power generated is transmitted through wires. To reduce transmission and distribution losses, researchers have drifted towards wireless energy transmission. The present paper discusses about the history, evolution, types, research and advantages of wireless power transmission. There are separate methods proposed for shorter and longer distance power transmission; Inductive coupling, Resonant inductive coupling and air ionization for short distances; Microwave and Laser transmission for longer distances. The pioneer of the field, Tesla attempted to create a powerful, wireless electric transmitter more than a century ago which has now seen an exponential growth. This paper as a whole illuminates all the efficient methods proposed for transmitting power without wires. —————————— —————————— INTRODUCTION Wireless power transfer involves the transmission of power from a power source to an electrical load without connectors, across an air gap. The basis of a wireless power system involves essentially two coils – a transmitter and receiver coil. The transmitter coil is energized by alternating current to generate a magnetic field, which in turn induces a current in the receiver coil (Ref 1). The basics of wireless power transfer involves the inductive transmission of energy from a transmitter to a receiver via an oscillating magnetic field. -

Critics on White Noise and Moon Palace. on Classification and Genre

Universiteit Utrecht MA – Westerse Literatuur en Cultuur: English Sarah Scholliers (3104591) Critics on White Noise and Moon Palace. On Classification and Genre Hans Bertens Onno Kosters July 2007 Table of Contents Introduction: On Classification 1 CHAPTER ONE: Genre(s) and Critics 4 Contemporary Criticism with Regard to Genre 5 Genres, Auster and DeLillo 9 Two Stories 10 Playing with Genres? 11 Moon Palace 11 White Noise 13 Conclusion 14 CHAPTER TWO: French Influences? 16 Derrida and the Instability of Language 17 Derridean Language in Auster and DeLillo 18 Lacan’s Theory of Language and the Unconscious: in Search of the Sublime 19 Lyotard and the Unpresentable 21 Auster’s and DeLillo’s Sublime: Echoes of Lacan and Lyotard, and Derridean examples 23 Baudrillard’s Simulation 27 A Baudrillardean Auster and DeLillo? 28 Conclusion 30 CHAPTER THREE: American Approaches 32 Postmodern Sublime 32 The Romantic Sublime 32 Space 32 Magic and Dread – The Question of Language 35 Systems Theory 39 Conclusion 42 General Conclusion 43 Bibliography 46 I would like to thank Professor Hans Bertens and Dr. Onno Kosters, my supervisor and co-supervisor respectively, for the careful reading of the first versions of my thesis. INTRODUCTION On Classification Most people have clear ideas about the nature of a work of art. They tend to classify it within a particular category with which they are familiar. They do so, based on their own experience with this (and other) artwork, on critics’ opinion, popular media or hearsay. In general, people approach works of art with an unambiguous view, and they classify a film as a comedy or a book as a thriller. -

A Novel Single-Wire Power Transfer Method for Wireless Sensor Networks

energies Article A Novel Single-Wire Power Transfer Method for Wireless Sensor Networks Yang Li, Rui Wang * , Yu-Jie Zhai , Yao Li, Xin Ni, Jingnan Ma and Jiaming Liu Tianjin Key Laboratory of Advanced Electrical Engineering and Energy Technology, Tiangong University, Tianjin 300387, China; [email protected] (Y.L.); [email protected] (Y.-J.Z.); [email protected] (Y.L.); [email protected] (X.N.); [email protected] (J.M.); [email protected] (J.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-152-0222-1822 Received: 8 September 2020; Accepted: 1 October 2020; Published: 5 October 2020 Abstract: Wireless sensor networks (WSNs) have broad application prospects due to having the characteristics of low power, low cost, wide distribution and self-organization. At present, most the WSNs are battery powered, but batteries must be changed frequently in this method. If the changes are not on time, the energy of sensors will be insufficient, leading to node faults or even networks interruptions. In order to solve the problem of poor power supply reliability in WSNs, a novel power supply method, the single-wire power transfer method, is utilized in this paper. This method uses only one wire to connect source and load. According to the characteristics of WSNs, a single-wire power transfer system for WSNs was designed. The characteristics of directivity and multi-loads were analyzed by simulations and experiments to verify the feasibility of this method. The results show that the total efficiency of the multi-load system can reach more than 70% and there is no directivity. Additionally, the efficiencies are higher than wireless power transfer (WPT) systems under the same conductions. -

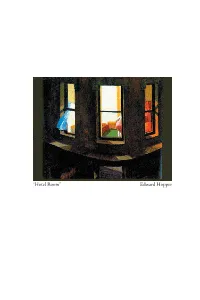

Edward Hopper the Light and the Fogg: Edward Hopper and Paul Auster

“Hotel Room” Edward Hopper The Light and the Fogg: Edward Hopper and Paul Auster James Peacock University of Edinburgh Auster contributed an extract from Moon Palace to the collection “Edward Hopper and the American Imagination,” and it is clear that Hopper’s images of alienated individuals have had a profound resonance for him. This paper employs two main ideas to compare them. First, a pivotal moment in American literature: the hotel room drama watched by Coverdale in Hawthorne’s Blithedale Romance. Secondly, Aby Warburg’s concept of the “pathos formula” in art, which bypasses the problematic issue of influence, choosing instead to posit sets of inherited cultural memories. It therefore allows discussion of the re-emergence of Hawthorne’s puritan tropes of paranoid specularity and transcendence in the work of Hopper and Auster. I was never able to paint what I set out to paint. (Edward Hopper, quoted in O’Doherty 77) Words are transparent for him, great windows that stand between him and the world, and until now they have never impeded his view, have never even seemed to be there. (G 146) Somewhere in New England in the nineteenth century, a man resumes his “post” (Hawthorne 168) at his hotel room window, there to observe the boarding house opposite. Before long, a “knot of characters” enters one of the rooms, appearing before our observer as if projected onto the physi- cal stage, having been “kept so long upon my mental stage, as actors in a drama.” Longing for “a catastrophe,” some moment of high theatre to fill the epistemological void of his own soul, our voyeur gazes with increasing intensity, fabricating scenarios which, he admits, “might have been alto- gether the result of fancy and prejudice in me.” When, in one of the most compelling and influential moments in all American literature, he is spot- ted by the female protagonist and barred from the scene by the dropping of a curtain, his appetite for narrative resolution remains unsated and he is condemned to brood on his isolation once more. -

“Then Catastrophe Strikes:” Reading Disaster in Paul Auster's Novels and Autobiographies « Then Catastrophe Strikes

Université Paris-Est Northwestern University École doctorale CS – Cultures et Sociétés Weinberg College of Arts & Sciences Laboratoire d’accueil : IMAGER Institut des Comparative Literary Studies Mondes Anglophone, Germanique et Roman, EA 3958 “T HEN CATASTROPHE STRIKES :” READING DISASTER IN PAUL AUSTER ’S NOVELS AND AUTOBIOGRAPHIES « THEN CATASTROPHE STRIKES » : LIRE LE DÉSASTRE DANS L’ŒUVRE ROMANESQUE ET AUTOBIOGRAPHIQUE DE PAUL AUSTER Thèse en cotutelle présentée en vue de l’obtention du grade de Docteur de l’Université de Paris- Est, et de Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature de Northwestern University, par Priyanka DESHMUKH Sous la direction de Mme le Professeur Isabelle ALFANDARY et de M. le Professeur Samuel WEBER Jury Mme Isabelle ALFANDARY , Professeur à l’Université Paris-3 Sorbonne Nouvelle (Directrice de thèse) Mme Sylvie BAUER , Professeur à l’Université Rennes-2 (Rapporteur) Mme Christine FROULA , Professeur à Northwestern University (Examinatrice) Mme Michal GINSBURG , Professeur à Northwestern University (Examinatrice) M. Jean-Paul ROCCHI , Professeur à l’Université Paris-Est (Examinateur) Mme Sophie VALLAS , Professeur à l’Université d’Aix-Marseille (Rapporteur) M. Samuel WEBER , Professeur à Northwestern University (Co-directeur de thèse) In memory of Matt Acknowledgements I wish I had a more gracious thank-you for: Mme Isabelle Alfandary , who, over the years has allowed me to experience untold academic privileges; whose constant and consistently nurturing presence, intellectual rigor, patience, enthusiasm and invaluable advice are the sine qua non of my growth and, as a consequence, of this work. M. Samuel Weber , whose intellectual generosity, patience and understanding are unparalleled, whose Paris Program in Critical Theory was critical in more ways than one, and without whose participation, the co-tutelle would have been impossible. -

Authorial Turns: Sophie Calle, Paul Auster and the Quest for Identity

Authorial Turns: Sophie Calle, Paul Auster and the Quest for Identity © Anna Khimasia, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-36802-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-36802-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. reproduced without the author's permission. In compliance with the Canadian Conformement a la loi canadienne Privacy Act some supporting sur la protection de la vie privee, forms may have been removed quelques formulaires secondaires from this thesis. -

Towner Award Nominee Books 2015 Electrical Wizard: How Nikola Tesla

Towner Award Nominee Books 2015 Electrical Wizard: How Publisher: Candlewick Press, Curriculum Connections: Electricity, magnets, physical science, Nikola Tesla Lit Up the Somerville, MA. 2013 alternating current vs. direct current, Nikola Tesla vs. Thomas Edison, inventions, patents/copyright, science fairs, World Genre/type: Biography, revolutionary ideas, biographies by Elizabeth Rusch storybook format Features: Illustrations, storybook format, index with Illustrations by Oliver specifics of Tesla’s life work, index of scientific notes & Dominguez diagrams of AC & DC currents, bibliography & further reading. As a young boy, Nikola Tesla had ideas ahead of his time. Tesla developed electricity using an alternating current that was safer and cheaper than the direct current developed by his hero-turned-rival Thomas Edison. A beautifully illustrated book in a story-telling, read-aloud format. Following are suggested resources for text-sets targeting the possible curriculum connections above. Books: Author Title/Publisher Grade Comments ISBN/Publication Levels Date Helfand, The Wright Brothers 3-8 This memorable graphic novel, tells the story of 978-9380028460 Lewis the Wright Brothers, their trials and tribulations c2011 Kalyani Navyug Media Pvt. growing up, becoming inventors, and their life after Genre/type: Ltd. their airplane invention. They struggled to patent Graphic and gain credit for their invention, just like Nikola Novel Tesla. The drawn visuals throughout the book (biography) help students quickly learn about the Wright brothers (in about 30-60 min.) and help the facts stick with you. Kamkwamba, The Boy Who Harnessed 2-6 As a young boy, William Kamkwamba’s village in 978-0803735118 William the Wind Malawi, Africa experienced a drought. -

Download the Story of My Typewriter, Paul Auster, Sam Messer, D.A.P

The story of my typewriter, Paul Auster, Sam Messer, D.A.P., 2002, 1891024329, 9781891024320, 63 pages. This is the story of Paul Auster's typewriter. The typewriter is a manual Olympia, more than 25 years old, and has been the agent of transmission for the novels, stories, collaborations, and other writings Auster has produced since the 1970s, a body of work that stands as one of the most varied, creative, and critcally acclaimed in recent American letters. It is also the story of a relationship. A relationship between Auster, his typewriter, and the artist Sam Messer, who, as Auster writes, "has turned an inanimate object into a being with a personality and a presence in the world." This is also a collaboration: Auster's story of his typewriter, and of Messer's welcome, though somewhat unsettling, intervention into that story, illustrated with Messer's muscular, obsessive drawings and paintings of both author and machine. This is, finally, a beautiful object; one that will be irresistible to lovers of Auster's writing, Messer's painting, and fine books in general.. DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1bs6nlL Hand to Mouth A Chronicle of Early Failure, Paul Auster, Aug 1, 2003, Biography & Autobiography, 169 pages. From the streets of Manhattan to Paris, a poignant memoir explains a series of ingenious and farfetched attempts to survive on next to no money, showing both the humor and .... Office Collectibles 100 Years of Business Technology, Thomas A. Russo, Jun 1, 2000, , 224 pages. This book presents the most comprehensive collection of antique and collectible office technology that has appeared to date. -

Tesla's Polyphase System and Induction Motor

SERBIAN JOURNAL OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING Vol. 3, No. 2, November 2006, 121-130 Tesla’s Polyphase System and Induction Motor Petar Miljanić1 1 Introduction While new scientific knowledge is acquired by learning, observation, experiments and thinking, the inventions are mostly the fruit of the intuition of individuals and of their creative impulses. Inventors are people who use consciously or unconsciously the accumulated human knowledge and experi- ence, and find useful solutions for the humanity. Some of those inventions are epochal, like for instance the inventions of the steam and the internal combustion engine. These epochal inventions obviously include the Tesla’s system of poly- phase alternate currents and Tesla’s induction motor. It can be often heard that in some eras of civilization there appear needs and there ripen circumstances for the appearance of great inventions. The sequence of the human acquisition of knowledge of natural phenomena on which the function of the induction motor is based, and the sequence of experiments in the attempt to make the induction motor show that that opinion is not without basis. In the following lines, we will tell the story of the induction motor. That story will not be limited to Tesla’s key contribution only, but it will mention things that happened before and after Tesla’s patent applications by the end of 1887. 2 Discoveries The induction motor rotates thanks to the natural phenomenon which may be described by the following words: the moving magnetic field of one part of the motor, for instance the stator, induces currents in the conducting parts of another part of the motor, the rotor. -

Tesla's Connection to Columbia University by Dr. Kenneth L. Corum

* Tesla’s Connection to Columbia University by Kenneth L. Corum and James F. Corum, Ph.D. “The invention of the wheel was perhaps rather obvious; but the invention of an invisible wheel, made of nothing but a magnetic field, was far from obvious, and that is what we owe to Nikola Tesla.” Professor Reginald Kapp, 1956 INTRODUCTION The Electrical Engineering curriculum at Columbia University, though not the first in the US, is one of the oldest and most respected EE programs in the world. From the beginning, a conscientious effort was made to base it on a foundation of science. It has been guided by the specific philosophy stated by Professor Michael Pupin: “Professor Crocker and I maintained that there is an ‘electrical science’ which is the real soul of electrical engineering.” Arguably the most stunning and significant lecture in modern history was presented one spring evening, more than a century ago, at Columbia University. The wealth of nations turned on its merits. Weighing on the balances would be our vast cities, civilization, and quality of life. But, what was it? . .Whatever it was, its impact has been as momentous for the progress and prosperity of civilization as the invention of the wheel! . It was Tesla’s great discovery and analysis of the rotating magnetic field, and a means for the electrical distribution of energy.1 As a result of the analysis presented in this lecture, the great Falls of Niagara would soon be harnessed for the benefit of mankind and launch civilization into the “Electromagnetic Century”. The Engineering Council for Professional Development (now called ABET) has defined “Engineering” as “that profession which utilizes the resources of the planet for the benefit of mankind”.