Lessons from Abroad: the Third Sector’S Role in Public Service Transformation ACEVO Is the Professional Body for Third Sector Chief Executives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fostering the Dialogue Between Citizens, Civil Society Organisations, National and European Institutions

European Commission DG – Communication Europe for Citizens Programme Fostering the Dialogue between Citizens, Civil Society Organisations, National and European Institutions. An Introduction to the European Year of Voluntary Activities promoting Active Citizenship European Year of Volunteering Rome: Quintilia Edizioni, 2011 ISBN: 88-900304-2-9 © ECP – Europe for Citizens Point Italy, 2011 Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged. This publication is co-financed by the European Commission. Printed in Italy European Year of Volunteering Fostering the Dialogue between Citizens, Civil Society Organisations, National and European Institutions. An Introduction to the European Year of Voluntary Activities promoting Active Citizenship. Edited by: Leila Nista - Rita Sassu Prefaces by: Patrizio Fondi Diplomatic Adviser, Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities Italy Gianni Bonazzi General Director, Service I, General Secretariat, Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities Italy Authors: Gianni Alemanno, Mayor of Rome Sophie Beernaerts, European Commission Gabriella Civico, European Year of Volunteering Alliance Silvia Costa, European Parliament Anna Cozzoli, European Commission, EACEA Emilio Dalmonte, European Commission Representation in Italy Paolo Di Caro, National Youth Agency Italy John Macdonald, European Commission Ramon Magi, Eurodesk Italy Leila Nista, Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities Italy Sabina Polidori, Ministry of Labour and Social Policies Italy Rita Sassu, ECP – Europe for Citizens Point -

Cabinet Office Annual Report and Accounts 2007 to 2008

Annual Report and Accounts 2007 – 2008 Making government HC613 work better This document is part of a series of Departmental Reports which along with the Main Estimates 2008–09, the document Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses 2008 and the Supplementary Budgetary Information 2008–09, present the Government’s expenditure plans for 2008–09 onwards, and comparative outturn data for prior years. © Crown Copyright 2008 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and other departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. For any other use of this material please write to Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU or e-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 9780 10 295666 5 Cabinet Office Annual Report and Accounts 2007–2008 Incorporating the spring Departmental Report and the annual Resource Accounts For the year ended 31 March 2008 Presented to Parliament by the Financial Secretary to the Treasury pursuant to the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 c.20,s.6 (4) Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 15 July 2008 London: The Stationery Office HC 613 £33.45 Contents 2 Cabinet Office Annual Report and Accounts 2007–08 Pages 4–11 INTRODUCTION -

Download (153Kb)

This article first appeared in December 2005’s edition of Professional Social Work magazine A Question of Principles What makes a Social Worker a Social Worker? There’s never been a more opportune moment to be writing this article on the essence of social work. The profession is at a critical point, in new potentially contradictory contexts. This discussion focuses mainly on developments in England but is relevant to emerging developments in the rest of the UK. With the introduction of the new social work degree from 2003, registration and protection of title of ‘social worker’ from April 2005, new financial investment in the form of bursaries for social work students and a new post-qualifications framework (by 2007), the future for social work looks rosy. Politically these changes have been owned and promoted: Stephen Ladyman described them as playing “an important part in raising standards in social work practice(1).” At the same time there have been changes, leading to ambiguity about the territory and importance of social work in its own right. ‘Social Care’ is now the predominant term used since the mid-‘90s rather than ‘social services’ and indeed ‘social work’, evidenced in the titles of the UK Care Councils. The question is, is it now an inclusive term relating to a wide range of care, of which social work is a highly qualified part, or does it represent a dilution of the special nature of social work into a more generic alternative to health care, mopping up all the areas of community based service as health services are more carefully redefined by cost and capacity? Thomas & Pierson (2001) define social care as “assistance given to people to maintain themselves physically and socially…in residential and day care centres and…at home,…distinguished from health care” and care given by a family member (2) – neatly avoiding all the contested areas that social work can include. -

Future Energy Systems in Europe

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT Science and Technology Options Assessment S T O A FUTURE ENERGY SYSTEMS IN EUROPE STUDY (IP/A/STOA/FWC-2005-28/SC20) IP/A/STOA/2008-01 PE 416.243 DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT A: ECONOMIC AND SCIENTIFIC POLICY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY OPTIONS ASSESSMENT FUTURE ENERGY SYSTEMS IN EUROPE STUDY Abstract The European energy sector faces critical challenges in the future. In order to shed light on different pathways towards achieving these goals a number of energy scenarios for the EU27 have been developed within this project. The focus of the scenario building procedure is on the overall energy system, showing how the different elements of the European energy systems interact with each other, and how different combinations of technology choices and policies lead to different overall results. The project explores two essentially different developments of the European energy systems through a so-called Small-tech scenario and a Big-tech scenario. Both scenarios aim at achieving two concrete goals for 2030: reducing CO2 emissions by 50 per cent compared to the 1990 level, and reducing oil consumption by 50 per cent compared to the present level. Among the project recommendations are saving energy (as being less expensive than producing energy), stimulate the development of district heating and district cooling grids to facilitate the utilization of waste heat, large-scale integration of variable renewable energy sources, strengthening and coordinating the European electricity infrastructure, three levels of transformation needed in the transport sector (fuel efficiency, introduction of electric vehicles and modal-change, new resources (the sustainable European biomass for energy purposes, municipal waste). -

13 16 03 Edition

June 2009 Issue Five IN PRESS IN PRESS Issue Five Corby Business Academy 1 03 Win a £50 Asda Voucher 13 Spirit of Corby Winner 16 Three Peaks Challenge STUDENT EDITION it’sit’s allall aboutabout ourour studentsstudents andand theirtheir future...future INNOVATIVE PARENTS INFORMATION SCHEME FROM OUR STUDENT EDITOR An innovative Corby Business Academy trial which up with new ways of communicating with parents. saw staff hold a parent information session in a Corby Welcome to the first ever student edition of In the future the plan is to roll the scheme out into In Press. supermarket has been hailed a success. local businesses which employ large numbers of CBA After four issues we thought it was time that A steady stream of parents went along to the first parents. the students picked up their notepads and session held at the Morrisons store in Oakley Road on microphones, so In Press Editor Ms Ashby May 16 to speak to staff about their child’s progress. has kindly handed over her role to myself for Principal Dr Andrew Campbell, said: “This has proved this edition. to be an excellent initiative and has been very helpful for The team of reporters representing each all those parents who came to visit us. It is yet another year group have been busy finding out what way in which CBA is developing a strong presence in the has been going on during this hectic May community and I am delighted that it has been so well term and inside these pages we will bring supported by staff and students alike. -

Building the European Federation of Public Service Unions the History – 2016) of EPSU (1978 Carola Fischbach-Pyttel

European Trade Union Institute Bd du Roi Albert II, 5 1210 Brussels Belgium +32 (0)2 224 04 70 [email protected] www.etui.org Building The European Federation of Public Service Unions will celebrate its 40th anniversary in 2018. the European Federation It is better known as “EPSU” (the “European Public Service Union”), a name that represents both the organisation’s mission statement and a key future ambition. of Public Service Unions This book retraces the development of EPSU, beginning with its early days as the European Public Services Committee (EPSC). The EPSC was set up as an ETUC liaison committee encompassing two organisations. It soon became obvious that this “marriage of convenience” The history of EPSU (1978 – 2016) between the organisations involved was a mismatch, and it came to an end in 1994 through a decision by the EPSC Presidium which was then formalised at the fifth General Assembly in — Vienna in 1996. The organisation was from then on to be called the European Federation of Carola Fischbach-Pyttel Public Service Unions (EPSU). The book also looks at the difficult development of the sectoral social dialogue in the public services sector and describes the problems that had to be overcome in this process. A constant challenge in EPSU’s work has been the various waves of public service liberalisation, ranging from public procurement and the Services Directive to the European energy market and, recently, the negotiation of various international trade deals. All these issues raise questions about the power relations that determine -

Tilburg University Babel Debates Szabo, Peter

Tilburg University Babel Debates Szabo, Peter Publication date: 2021 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Szabo, P. (2021). Babel Debates: An ethnographic language policy study of EU Multilingualism in the European Parliament. [s.n.]. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. sep. 2021 Babel Debates An ethnographic language policy study of EU Multilingualism in the European Parliament To the memory of Jan Blommaert Babel Debates An ethnographic language policy study of EU Multilingualism in the European Parliament PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University, op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. W.B.H.J. van de Donk, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de Aula van de Universiteit op vrijdag 26 februari 2021 om 13.30 uur door Péter Károly Szabó geboren te Boedapest, Hongarije Promotores: prof. -

OWMT Newsletter 2007

The Old Wandsworthians’ Merry Christmas and a Memorial Trust Happy New Year Newsletter No.14. December 2007 HRK Remembered H. Raymond King was Headmaster at Wandsworth School from 1932 to 1963. He suc- ceeded Dr H. Waite who had held the post since 1900. Two headmasters in 63 years sug- gests stability and a devotion to duty. To H. Raymond King duty, diligence and respect were extremely important. The son of a railwayman he attended King Edward V1 School at East Retford; leaving at the age of eighteen to join the army and serve on the Western Front. He rose to the rank of Company Sergeant Major and won the D.C.M, M.M and Croix de Guerre for bravery. In 1919 he went up to Cambridge and ended his time there at the University Training College for Teachers. He had chosen his profession and after teaching at Westminster School and Portsmouth Grammar School he joined Scarborough High School as Headmaster where he developed and introduced the set system we all remember proudly from our days at Wandsworth. He entered the London County Council educational system as headmaster at Forest Hill in 1930 and accepted the post at Wandsworth two years later. King was a visionary who not only introduced the tutorial system, diligence assessments ,the Parents Association and a Careers Master, but was also instrumental in the building H. Raymond King of the fives courts and swimming pool. He pioneered international student exchanges and CBE; DCM; MM; the introduction of Technical Studies alongside the more academic grammar stream. -

European Parliament

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 2004 2009 Session document FINAL A6-9999/2006 20.12.2006 REPORT on corporate social responsibility: a new partnership (2006/2133(INI)) Committee on Employment and Social Affairs Rapporteur: Richard Howitt RR\380802EN.doc PE 380.802v02-00 EN EN PR_INI CONTENTS Page MOTION FOR A EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT RESOLUTION ............................................ 3 EXPLANATORY STATEMENT............................................................................................ 17 OPINION OF THE COMMITTEE ON INDUSTRY, RESEARCH AND ENERGY............ 21 OPINION OF THE COMMITTEE ON WOMEN'S RIGHTS AND GENDER EQUALITY 24 PROCEDURE .......................................................................................................................... 27 PE 380.802v02-00 2/2 RR\380802EN.doc EN MOTION FOR A EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT RESOLUTION on corporate social responsibility: a new partnership (2006/2133(INI)) The European Parliament, – having regard to the two most authoritative internationally agreed standards for corporate conduct: the International Labour Organization's Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy and the OECD's "Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises", and to codes of conduct agreed under the aegis of international organisations such as the FAO, the World Health Organization and the World Bank and efforts under the auspices of UNCTAD with regard to the activities of enterprises in developing countries, – having regard to the ILO Declaration on Fundamental -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Monday Volume 504 25 January 2010 No. 29 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 25 January 2010 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2010 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 531 25 JANUARY 2010 532 Mr. Coaker: I do not accept that numeracy and House of Commons literacy standards are nowhere near where they should be—a significant rise has taken place in those standards. Monday 25 January 2010 The number of primary school pupils gaining level 4, which is the benchmark that we use, has risen significantly. I mentioned the GCSE results at Battersea Park school, The House met at half-past Two o’clock but the results of other secondary schools up and down the country also show a significant improvement. Are we satisfied with that and do we want to do more? Of PRAYERS course we want to do more, which is why we are introducing one-to-one tuition in primary schools. Such tuition will be carried on into secondary schools and [MR.SPEAKER in the Chair] will be backed up by the resources and investment needed. Oral Answers to Questions Ms Karen Buck (Regent’s Park and Kensington, North) (Lab): Is my hon. Friend aware that the number of pupils obtaining five good GCSEs in Westminster has more than doubled since 1997? Will he join me in CHILDREN, SCHOOLS AND FAMILIES congratulating Martin Tissot and the teachers and pupils at St. -

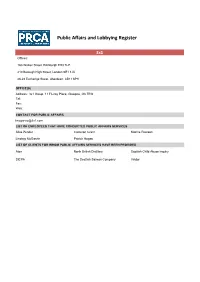

Public Affairs and Lobbying Register

Public Affairs and Lobbying Register 3x1 Offices: 16a Walker Street, Edinburgh EH3 7LP 210 Borough High Street, London SE1 1JX 26-28 Exchange Street, Aberdeen, AB11 6PH OFFICE(S) Address: 3x1 Group, 11 Fitzroy Place, Glasgow, G3 7RW Tel: Fax: Web: CONTACT FOR PUBLIC AFFAIRS [email protected] LIST OF EMPLOYEES THAT HAVE CONDUCTED PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES Ailsa Pender Cameron Grant Katrine Pearson Lindsay McGarvie Patrick Hogan LIST OF CLIENTS FOR WHOM PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES HAVE BEEN PROVIDED Atos North British Distillery Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry SICPA The Scottish Salmon Company Viridor Public Affairs and Lobbying Register Aiken PR OFFICE(S) Address: 418 Lisburn Road, Belfast, BT9 6GN Tel: 028 9066 3000 Fax: 028 9068 3030 Web: www.aikenpr.com CONTACT FOR PUBLIC AFFAIRS [email protected] LIST OF EMPLOYEES THAT HAVE CONDUCTED PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES Claire Aiken Donal O'Neill John McManus Lyn Sheridan Shane Finnegan LIST OF CLIENTS FOR WHOM PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES HAVE BEEN PROVIDED Diageo McDonald’s Public Affairs and Lobbying Register Airport Operators Associaon OFFICE(S) Address: Airport Operators Association, 3 Birdcage Walk, London, SW1H 9JJ Tel: 020 7799 3171 Fax: 020 7340 0999 Web: www.aoa.org.uk CONTACT FOR PUBLIC AFFAIRS [email protected] LIST OF EMPLOYEES THAT HAVE CONDUCTED PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES Ed Anderson Henk van Klaveren Jeff Bevan Karen Dee Michael Burrell - external public affairs Peter O'Broin advisor Roger Koukkoullis LIST OF CLIENTS FOR WHOM PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES HAVE BEEN PROVIDED N/A Public Affairs and -

2008 RGD Speakers

Norbert Teufelberger, Chairman of EGBA, Co-Chief Executive Officer, bwin Norbert Teufelberger was born in 1965 and graduated from Vienna University of Economics with a degree in social science and economics. His work experience in the international casino industry goes back to 1989, when he joined Casinos Austria AG, Vienna, as assistant to the head of the Foreign Business Division. In 1992 he was appointed head of the International Finance and Controlling Department. At the end of 1992, after working for two months as a consultant to the Novomatic Group, Gumpoldskirchen, he founded Century Casinos, Inc., Cripple Creek, Colorado, together with former colleagues, serving as the company’s sole finance director and a member of the board until September 1999. The company was listed on NASDAQ in 1996. On 19 January 2000, he was appointed to the Management Board with responsibility for finance and investor relations. In June 2001 he was appointed Co-CEO and also assumed responsibility for the operational business and all gaming activities. Christofer Fjellner, Member of the European Parliament, EPP-ED, Sweden Christofer Fjellner is Member of the European Parliament. He is Member of the Committee of International Trade, Member of the Committee of Budget Control, Supplementary Member of the Committee of Environment and Public Health, Member of the Parliamentary Delegation to Belarus and Supplementary Member of the Parliamentary Delegation to Iran. He is also Member of the executive board of Moderaterna (the Swedish conservatives) and Vice-President of Look Closer AB (a business intelligence company that he co-founded in 2000). From 2002 to 2004, Mr.