Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Bad Cops: a Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers Author(s): James J. Fyfe ; Robert Kane Document No.: 215795 Date Received: September 2006 Award Number: 96-IJ-CX-0053 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers James J. Fyfe John Jay College of Criminal Justice and New York City Police Department Robert Kane American University Final Version Submitted to the United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice February 2005 This project was supported by Grant No. 1996-IJ-CX-0053 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of views in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Examining Television Narrative Structure

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Scholarship and Professional Work - Communication College of Communication 2002 Re(de)fining Narrative Events: Examining Television Narrative Structure M. J. Porter D. L. Larson Allison Harthcock Butler University, [email protected] K. B. Nellis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ccom_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Porter, M.J., Larson, D.L., Harthcock, A., & Nellis, K.B. (2002). Re(de)fining narrative events: Examining television narrative structure, Journal of Popular Film and Television, 30, 23-30. Available from: digitalcommons.butler.edu/ccom_papers/9/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Communication at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarship and Professional Work - Communication by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Re(de)fining Narrative Events: Examining Television Narrative Structure. This is an electronic version of an article published in Porter, M.J., Larson, D.L., Harthcock, A., & Nellis, K.B. (2002). Re(de)fining narrative events: Examining television narrative structure, Journal of Popular Film and Television, 30, 23-30. The print edition of Journal of Popular Film and Television is available online at: http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/VJPF Television's narratives serve as our society's major storyteller, reflecting our values and defining our assumptions about the nature of reality (Fiske and Hartley 85). On a daily basis, television viewers are presented with stories of heroes and villains caught in the recurring turmoil of interrelationships or in the extraordinary circumstances of epic situations. -

Kelly Mantle

The VARIETY SHOW With Your Host KELLY MANTLE KELLY MANTLE can be seen in the feature film Confessions of a Womanizer, for which they made Oscars history by being the first person ever to be approved and considered by The Academy for both Supporting Actor and Supporting Actress. This makes Kelly the first openly non-binary person to be considered for an Oscar. They are also featured in the movie Middle Man and just wrapped production on the upcoming feature film, God Save The Queens in which Kelly is the lead in. TV: Guest-starred on numerous shows, including Lucifer, Modern Family, Curb Your Enthusiasm, CSI, The New Normal, New Adventures of Old Christine, Judging Amy, Nip/Tuck, Will & Grace, George Lopez. Recurring: NYPD Blue. Featured in LOGO’s comedy special DragTastic NYC, and a very small co-star role on Season Six of RuPaul's Drag Race. Stage: Kelly has starred in more than 50 plays. They wrote and starred in their critically acclaimed solo show,The Confusion of My Illusion, at the Los Angeles LGBT Center. As a singer, songwriter, and musician, Kelly has released four critically acclaimed albums and is currently working on their fourth. Kelly grew up in Oklahoma like their uncle, the late great Mickey Mantle. (Yep...Kelly's a switch-hitter, too.) Kelly received a B.F.A. in Theatre from the University of Oklahoma and is a graduate of Second City in Chicago. https://www.instagram.com/kellymantle • https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0544141/ ALEXANDRA BILLINGS is an actress, teacher, singer, and activist. -

A Course Whose Time Has Come

A course whose time has come Paul R. Joseph Law is a central component of the democratic State. It defines the relation between the government and its people and sets the rules (and limits) of the restrained warfare of politics. Law becomes the battle ground for moral debates about issues such as abortion, discrimination, euthanasia, pornography and religion. Today we also debate the role Using science fiction and functioning of the legal system itself. Are lawyers ethical? Do judges usurp the legislative role? Are there too many ‘frivolous’ law materials to teach law. suits? Law and popular culture Where do the masses of people learn about the law? What shapes their views? Some peruse learned treatises, others read daily newspapers or tune in to the nightly news. Some watch key events, such as Supreme Court confirmation hearings, live, as they happen. Some have even been to law school. Many people also rely (whether consciously or not) on popular culture for their understanding of law and the legal system. Movies, television programs and other popular culture elements play a dual role, both shaping and reflecting our beliefs about the law. If popular culture helps to shape the public’s view about legal issues, it also reflects those views. By its nature as a mass commercial product, popular culture is unlikely to depart radically from images which the public will accept. By examining popular culture, we, the legally trained, can get an idea about how we and the things we do are understood and viewed by the rest of the body politic. -

Extensions of Remarks E643 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

April 2, 2003 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E643 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS REMEMBERING FORMER TRENTON promise and opportunity for this and future GLOBAL CHANGE RESEARCH AND MAYOR TOMMIE GOODWIN generations. DATA MANAGEMENT ACT OF 2003 The spirit of community service is alive and HON. JOHN S. TANNER thriving in Fremont, in some major part due to HON. MARK UDALL OF TENNESSEE the efforts of the members of the Mission San OF COLORADO IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Jose Rotary Club. I am honored to commend IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Wednesday, April 2, 2003 the Mission San Jose Rotary Club for its 20 Wednesday, April 2, 2003 years of generous service to the community. Mr. TANNER. Mr. Speaker, today I want to Mr. UDALL of Colorado. Mr. Speaker, today tell you about Tommie Goodwin, a fine public I am pleased to introduce the Global Change servant who dedicated himself to the people of f Research and Data Management Act of 2003. This bill updates the existing law that formally Tennessee during a distinguished 20-year ten- RECOGNITION TO MR. BILL CLARK ure as mayor of the City of Trenton, Ten- established the U.S. Global Change Research nessee. Program (USGCRP) in 1990. This bill is also Tommie first became mayor of Trenton in similar to the Global Change Research and 1983 and served honorably in that capacity HON. FRANK PALLONE, JR. Data Management Act that I introduced in the until his passing last year. Under Mayor Good- OF NEW JERSEY 107th Congress. Over the past decade, the USGCRP has win’s leadership, our community made great IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES strides in economic development and improve- significantly advanced our scientific knowledge ments in the quality of life of our citizens. -

Breath and Breathlessness (Reflections from the Long Road of My Healing) April 11T H, 2021 Rev

Breath and Breathlessness (Reflections from the Long Road of My Healing) April 11t h, 2021 Rev. Dr. Leon Dunkley North Universalist Chapel Society Good morning and good Sunday. I hope that this new day finds you well. My name is Leon Dunkley and I am honored to serve as minister to North Universalist Chapel Society (or North Chapel) in Woodstock, Vermont. Today is Sunday, April 11 th and the title of this morning’s reflection is Breath and Breathlessness—Reflections from the Long Road of My Healing. To all souls, I say, “Good morning. It is good to be together.” Maya Angelou proclaimed, “Life is not measured by the number of breaths we take, but by the moments that take our breath away.” The sacredness of life is measured not by time but by timelessness…by the experiences in life that leave us breathless. Maya Angelou was an artist. She was a poet. She was careful with her words, careful with her meaning…with her healing messages. Poems are like remedies. They are like a little games of words—combed and measured, braided in near-perfect rows. Corn, collard, ochre-green. Lean words, wise and healthy. Fresh and tender to the touch. Maya was a poet. She captured the sun-hot intimacy of living and reflected it back to us, as sunrise…as nebula, comet and constellation, as black hole and as supernova. She reminded us that there are many great struggles in life—between enslavement and real freedom, between greed and true ambition. She’d say, “The desire to reach for the stars is ambitious. -

What Would Sipowicz Do? Race, Rights and Redemption in NYPD Blue

E D I T E D BY GLENN YEFFETH What Would Sipowicz Do? Race, Rights and Redemption in NYPD Blue BENBELLA BOOKS Dallas, Texas JEFFREY SCHALER Just One Sip for Sipowicz to Slip Like the New York background, Sipowicz’s alcoholism is a cen- tral, if not explicitly mentioned, aspect of NYPD Blue. Sipowicz is an alcoholic, and we all know what that means. Or do we? “Yee doe here but sippe of this cuppe, but then ye shall drinke up the dreggs of it for ever.” —JOHN PRESTON (Breastplate of Faith and Love) NDY SIPOWICZ, our lion-hearted, lily-livered, existential hero, is an “alcoholic.” Sipowicz is drunk in the very fi rst episode of Athe series and wrestles with his alcoholism throughout the en- tire run of the show. Sipowicz’s alcoholism has wrecked his marriage, destroyed most of his relationships and by the end of the fi rst episode is on the verge of ruining his career. Many people struggle with alcohol problems; these problems mani- fest themselves in many ways and are solved—or not—in an equally wide variety of ways. As an expert in the fi eld of addiction and drug policy, I’ve studied the various techniques problem drinkers use to ad- dress their drinking—and the effectiveness of these techniques. I’ll get to this later, but fi rst I want to discuss the most widely known approach to addressing alcohol problems: Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). 63 64 • JEFFREY SCHALER AA has been so successful in popularizing its approach to heavy drinking that many people don’t even realize that its approach is only one of many. -

1997 Wilbur Award Winners

Religion Communicators Council An Interfaith Association of Religion Communicators since 1929 1997 Wilbur Awards for work completed in 1996 Presented April 1, 1997 in Boston, Massachusetts Television Films (or Films, Television) • Hallmark Entertainment, Captive Heart: The James Mink Story," Dorothea Petrie, Michael Spivak, executive producers; Wendy Grean, producer; Bryon White, writer, Bruce Pittman, director Newspapers: Other Markets • News & Record, Greensboro, North Carolina, "And Remember Their Sin No More," Sunday, April 7, 1996, Lex Alexander, staff writer; Joseph Rodriguez, photographer; Ed Williams, editor Magazines: National Circulation • The Atlantic Monthly, "Welcome to the Next Church," Charles Trueheart, writer, (photo-various) • Life, "The Mystery of Mary," Robert Sullivan, writer; Cynthia Fox, reporter; Mimi Murphy and Josh Simon, additional reporting, December, 1996 (photos—various) Television: News, Local • KTTV, Los Angeles, Fox News 11, , "Tyndale Bible Exhibit," 10 O'Clock News, November 17, 1996, Sam Hall Kaplan, reporter/ Producer, Videographer • KOTV-TV, Tulsa Oklahoma, "The Long Journey Home," February 10, 11, 12, 1996, Catherine Curtin, Charlene Shirk, Michael Jenkins, creative staff reporter/Producer, Videographer Magazines: Local/Specialized Circulation • O.C. Metro, "Viewpoint Column," Hugh Hewitt, writer Television: Documentary, National • Public Affairs Television, "The Wisdom of Faith With Huston Smith," Bill Moyers, Pamela Mason Wagner, writer, producer; , videographer; , editor. Religion Communicators Council 475 Riverside Drive, New York, NY 10115 | 212-870-2985 | www.religioncommunicators.org Religion Communicators Council An Interfaith Association of Religion Communicators since 1929 1997 Wilbur Awards for work completed in 1996 Television: Documentary, Local • WTHR-TV,Indianapolis, IN, "In the Arms of Mother Teresa," Anne Ryder, reporter/writer/field producer; Steve Starnes, photographer/editor. -

Join Me in Houston!

JOIN ME IN HOUSTON! ACTING WORKSHOP with Carol Hickey Saturday, Dec. 5th 2-8pm $125 Ages 16 + Carol Hickey has studied with some of the most prestigious instructors in Acting at HB Studio in New York and 7 years in Los Angeles with Harry Mastrogeorge. She has a degree in Theatre from University of California, Santa Barbara. She earned her living working on commercials and television series (Gilmore Girls, Six Feet Under, Scrubs, ER, NYPD Blue, Judging Amy, Big Love, National Tide, AT&T, Kelloggs, Cisco and many more) in Los Angeles. She also has received awards for her work on stage, developing premiere works in Los Angeles and in New York with The Canyon Theatre Company, along with name actors such as Mark Ruffalo and Kathy Bates. Recently she has played opposite Lance Henriksen in Spirit Riders, Jen Kirkman in her Netflix comedy special and Mike Doyle in The Last Word. “Carol Hickey is one of the most naturally gifted people I have ever had the privilege and distinct pleasure of working with. She has, above and beyond normal, a natural child-like innocence, an unlimited imagination, and a vulnerability that has no boundaries. Anyone who has the good fortune to work with Carol, in any capacity, is truly privileged and on track to develop into becoming an actor of stature. It takes a lot of hard work and discipline, but with Carol as a guide, example, and mentor you are well on your way.” - Harry Mastrogeorge The workshop will focus on defining the job of an actor and the disciplined practice of training the imagination to create a second reality using the script as a road map. -

Pasha Lychnikoff

Pasha Lychnikoff SAG/AFTRA FILM BULLET TRAIN Supporting Columbia Pictures David Leitch LAST MOMENT OF CLARITY Lead Metalwork Pictures Colin Krisel FOLLOW ME Lead Escape Productions Will Wernick SIBERIA Lead Buffalo Gal Pictures Matthew Ross BEYOND VALKYRIE: DAWN OF THE 4TH Lead Destination Films Claudio Fah REICH RAGE Lead Patriot Pictures Paco Cabezas A GOOD DAY TO DIE HARD Supporting Twentieth Century Fox John Moore CHERNOBYL DIARIES Lead Alcon Entertainment Bradley Parker BUCKY LARSON: BORN TO BE A STAR Supporting Columbian Pictures Tom Brady VALLEY OF THE SUN Lead Hotbed Media Stokes McIntyre STAR TREK ('09) Supporting Paramount Pictures J.J. Abrams INDIANA JONES 4 Supporting Paramount Pictures Steven Spielberg CHARLIE WILSON'S WAR Supporting Universal Pictures Mike Nichols A THOUSAND YEARS OF GOOD PRAYERS Lead Boram Entertainment Wayne Wang TRADE Lead Lionsgate Centropolis THE PERFECT SLEEP Supporting Unified Pictures Jeremy Alter RESERVATIONS Lead Altogether Alone Aloura Melissa Charles MIAMI VICE Supporting Universal Pictures Michael Mann PLAYING GOD Supporting Beacon Communications Andy Wilson AIR FORCE ONE Featured Columbia Pictures Wolfgang Peterson TELEVISION STRANGER THINGS Recurring Guest Star Netflix Various QUEEN OF THE SOUTH Recurring Guest Star USA Various GOOD GIRLS Recurring Guest Star NBC Michael Weaver MARISA ROMANOV Recurring Guest Star Amazon Miranda K. Spigener RAY DONOVAN Recurring Guest Star SHOWTIME John Dahl SHAMELESS Recurring Guest Star SHOWTIME Mark Mylod MAGNUM P.I. Guest Star CBS Bryan Spicer SIX Guest Star HISTORY CHANNEL Kimberly Peirce MACGYVER Guest Star CBS Stephen Herek INSOMNIA Series Regular Independent Slava N. Jakovleff THE BRAVE Guest Star NBC John Terlesky N.C.I.S: LOS ANGELES Recurring Guest Star CBS Dennis Smith ELEMENTARY Guest Star CBS Guy Ferland FIZRUK Recurring Guest Star Telekanal TNT - Russia Dmitry Gubarev ALLEGIANCE Recurring Guest Star NBC George Nolfi THE BLACKLIST Guest Star NBC Michael W. -

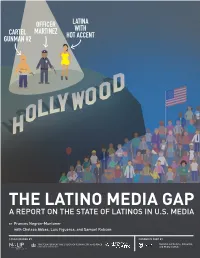

The Latino Media Gap a Report on the State of Latinos in U.S

OFFICER LATINA MARTINEZ WITH CARTEL HOT ACCENT GUNMAN #2 THE LATINO MEDIA GAP A REPORT ON THE STATE OF LATINOS IN U.S. MEDIA BY Frances Negrón-Muntaner with Chelsea Abbas, Luis Figueroa, and Samuel Robson COMMISSIONED BY FUNDED IN PART BY The Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race National Latino Arts, Education, Columbia University and Media Institute Latinos are a powerful force in featuring compelling Latino talent and American society. Topping ffty-three storylines are rewarded with high EXECUTIVE million, Latinos constitute one of the ratings and revenue. fastest growing ethnic groups in the SUMMARY United States, comprising 17% of Yet, with few exceptions, Latino the population and over 20% of the participation in mainstream English- AND key 18–34 marketing demographic.1 language media is stunningly low. A Relative to the general population, review of the top movies and television KEY FINDINGS Latinos also attend more movies and programs reveals that there is a narrower listen to radio more frequently than range of stories and roles, and fewer do any other U.S. racial or ethnic Latino lead actors in the entertainment group.2 In addition, their purchasing industry today, than there were seventy power is steadily increasing. By 2015, years ago. Likewise, whereas the Latino Hispanic buying power is expected to population grew more than 43% reach $1.6 trillion. To put this fgure from 2000 to 2010, the rate of media in perspective: if U.S Latinos were to participation—behind and in front found a nation, that economy would be of the camera, and across all genres the 14th largest in the world.3 and formats—stayed stagnant or grew only slightly, at times proportionally Latinos are not only avid media declining.5 Even further, when Latinos consumers; they have made important are visible, they tend to be portrayed contributions to the flm and television through decades-old stereotypes as industries, and currently over-index criminals, law enforcers, cheap labor, as digital communicators and online and hypersexualized beings.