A Theory of Everything to Do with Loxley. 1. Britons Stop the Anglo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cambridge Songs; a Goliard's Song Book of the 11Th Century

'm )w - - . ¥''•^^1 - \ " .' /' H- l' ^. '' '. H ,' ,1 11 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/cambridgesongsgoOObreuuoft THE CAMBRIDGE SONGS CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS C. F. CLAY, Manager EonDon: FETTER LANE, E.C CFDinburg!): loo PRINCES STREET SriB gotfe : G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS Smnbag, Calrutta anB iWalraa: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd. arotonto: J. M. DENT AND SONS, Ltd. Cokjo: THE MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA All rights resenied THE CAMBRIDGE SONGS A GOLIARD'S SONG BOOK OF THE XIth century EDITED FROM THE UNIQUE MANUSCRIPT IN THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BY KARL BREUL Hon. M.A., Litt.D., Ph.D. SCHRODER PROFESSOR OF GERMAN IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE Cambridge: -^v \ (I'l at the University Press j^ ^l^ Cambntgc: PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS PR nib IN MEMORIAM HENRICI BRADSHAW ET IN HONOREM FRANCISCI JENKINSON HOC OPVSCVLVM DEDICATVM EST PREFACE THE remarkable collection of Medieval Latin poems that is known by the name ' of The Cambridge Songs ' has interested me for more than thirty years. ' My first article Zu den Cambridger Liedern ' was written in the spring of 1885 and published in Volume xxx of Haupt's Zeitschrift filr deutsches Altertkum. The more attention I paid to the songs and the more I corresponded with scholars about some of them, the stronger became my conviction of the importance of having the ten folios of this unique manuscript photographed and of thereby rendering this fascinating collection in its every aspect readily accessible to the students of Medieval literature. It is in truth necessary to invite the co-operation of all such students, whether their subject be Medieval theology, philology, philosophy or music, in the interesting task of elucidating the more difficult poems of what may be regarded as the song book or commonplace book of some early Goliard. -

Saturday Walkers Club SWC Walks Walk 224. Kingham to Moreton In

Saturday Walkers Club SWC Walks Walk 224. Kingham to Moreton in Marsh via Adelstrop (the First World War Remembrance Walk) This Cotswolds walk is best done in “high summer” - late June to mid August - when there is maximum daylight (and hopefully sunlight!) to enjoy the dreamy Cotswolds landscape of flower-filled meadows, gentle hills and picturesque villages and churches. After periods of rain some paths and fields, particularly before lunch, will be boggy so this walk is best done and appreciated after a spell of dry, sunny weather. The walk is not recommended for autumn or winter. The walk first follows paths across fields near the river Evenlode and then passes through a number of lovely Cotswolds villages with its centrepiece a visit to the idyllic hamlet of Adelstrop, immortalised in the poem “Adelstrop” by Edward Thomas who died at the battle of Arras in France in 1917. Your recommended pub stop the Fox Inn at Lower Oddington is just 5.7km into the walk so you will have 12.0 km to complete after lunch (or 13.7km if you do the longer route from Adelstrop to Chastleton.). Jane Austen visited Adelstrop House at least three times and it is thought her novel Mansfield Park was inspired by the village and the surrounding area. The walk is on the Oxfordshire/ Gloucestershire borders and a long way from London and as you will not start walking until around noon (but earlier if you take the 9.22 Sunday train) you should prepare for a long day (12 hours) as there is much to see and enjoy. -

Lavender Cottage Evenlode, Moreton-In-Marsh

established 200 years Lavender Cottage £1,300 PCM Evenlode, Moreton-in-Marsh A detached period Cotswold stone cottage with three bedrooms and a courtyard garden, overlooking the village green. To let unfurnished for 6/12 months possibly longer. taylerandfletcher.co.uk T 01451 830383 Stow-on-the-Wold established 200 years Tel. 01285 623000 Stow-on-the-Wold 4 miles, Moreton-in-Marsh 3 miles, Cheltenham 24 miles Council Tax Band E Services Lavender Cottage Mains electricity, water and drainage are connected to the property. Please Note that we have not tested any Evenlode equipment, appliances or services. Moreton-in-Marsh Description Gloucestershire Lavender Cottage is an attractive detached period Cotswold cottage constructed of natural Cotswold stone under a slate GL56 0NN roof. The cottage enjoys a lovely aspect to the front A DETACHED PERIOD COTSWOLD STONE overlooking the village green. The cottage was extended and COTTAGE WITH THREE BEDROOMS AND A modernised in 2008. COURTYARD GARDEN, OVERLOOKING THE VILLAGE GREEN. TO LET UNFURNISHED FOR 6/12 MONTHS POSSIBLY LONGER. Front door with canopy leading into • Sitting Room Hallway • Dining Room Stone tiled floor throughout ground floor. • Kitchen Stairs off. Door to:- • Wet Room Sitting Room • Utility Room Open fire with stone hearth and wooden surround. Window to front aspect with cushion seat and curtains. • 3 Bedrooms • Bathroom • Courtyard Garden • Garage VIEWING Strictly by prior appointment through Tel: 01451 830383 Directions From Stow-on-the-Wold follow the A436 towards Chipping Norton. Immediately after the railway bridge turn left signed Adlestrop and Evenlode. At the T junction turn left signed Evenlode 1½ miles. -

Emma of Normandy, Urraca of León-Castile and Teresa of Portugal

Universidade de Lisboa Faculdade de Letras The power of the Genitrix - Gender, legitimacy and lineage: Emma of Normandy, Urraca of León-Castile and Teresa of Portugal Ana de Fátima Durão Correia Tese orientada pela Profª Doutora Ana Maria S.A. Rodrigues, especialmente elaborada para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em História do Género 2015 Contents Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………. 3-4 Resumo............................................................................................................... 5 Abstract............................................................................................................. 6 Abbreviations......................................................................................................7 Introduction………………………………………………………………..….. 8-20 Chapter 1: Three queens, three lives.................................................................21 -44 1.1-Emma of Normandy………………………………………………....... 21-33 1-2-Urraca of León-Castile......................................................................... 34-39 1.3-Teresa of Portugal................................................................................. 39- 44 Chapter 2: Queen – the multiplicity of a title…………………………....… 45 – 88 2.1 – Emma, “the Lady”........................................................................... 47 – 67 2.2 – Urraca, regina and imperatrix.......................................................... 68 – 81 2.3 – Teresa of Portugal and her path until regina..................................... 81 – 88 Chapter 3: Image -

A Heaven for Horsemen

iving in the Cotswolds Olympic without a horse is, quite eventer Vittoria frankly, a waste, because Panizzon, it’s a honey pot for horsey in Italian team A heaven for Lpeople, both professional and ama- livery, loves her teur. Horses emerge elegantly from Adlestrop base attractive yards built from mellow, horsemen yellow Cotswold stone to compete at the top European competitions, as well as Badminton, gatcombe, Hunting, hacking, polo and racing, Blenheim and Salperton horse trials, not to mention the major three-day events: which are on the doorstep, and riders are drawn to the range of competition they’re all there in the Cotswolds. centres, cross-country courses and easy access to the motorway network. Catherine Austen talks to leading equestrian Olympic dressage gold medallist figures who say they couldn’t live anywhere else Laura Bechtolsheimer has an enviable set-up at her parents’ home in Ampney Photographs by Richard Cannon I fell in love St Peter, outside Cirencester in glouces- tershire. She’s now married to seven- with this beautiful goal polo player Mark Tomlinson and place‘ and its great the high-powered couple lives between there and his family’s yard near Weston- social scene birt—the area is a hotspot for polo, too, with at least four clubs, including Cirencester Park and Beaufort. Eventers, such as Olympic gold ’ medallist Richard Meade and now his son, Harry, and racehorse trainers are drawn to the hills—perfect for gallop- ing horses up—and the Cotswolds’ ➢ The eventer vittoria Panizzon, who competed for italy at the Beijing and London Olympics, discovered the Cotswolds while at Bristol University. -

IF P 25 MIIBHIIN I MARSH IHIIIIBESTERSIIIIIE

Reprinted from: Gloucestershire Society for Industrial Archaeology Journal for 1977-78 pages 25-29 INDUSTRIAL ABIZIIIEIILIIGY (IF p 25 MIIBHIIN I MARSH IHIIIIBESTERSIIIIIE BIIY STIPLETUN © ANCIENT ROADS An ancient way, associated with the Jurassic Way, entered the county at the Four Shire Stone (SP 231321). It came from the Rollright Stones in Oxfordshire and followed the slight ridge of the watershed between the Thames and the Severn just north of Moreton in Marsh. Its course from the Four Shire Stone is probably marked by the short stretch of county boundary across Uolford Heath to Lemington Lane. The subsequent line is diffi- cult to determine; it may have struck north west across Batsford Heath to Dorn or, perhaps more likely, may have continued along Lemington Lane around the eastern boundary of the Fire Service Technical College, so skirting the marshy area of Lemington and Batsford Heaths. In the latter case, it would have continued across the Moreton in Marsh-Todenham road and along the narrow lane past Lower Lemington which crosses the Ah29 road (the Fosse Way) to Dorn. From there it would have continued to follow approximately the line of this road up past Batsford and along the ridge above to the course followed by the Ahh, thence following the Cotswold Edge southwards. The Salt Hay from Droitwich through Campden followed the same route through Batsford and Dorn to the Four Shire Stone, where it divided into two routes. One followed the same line as the previous way through Kitebrook and past Salterls Hell Farm near Little Compton to the Ridgeway near the Rollright Stones. -

MORETON in MARSH MARCH 2019 • ISSUE 148 Cotswoldtimes

MORETON IN MARSH MARCH 2019 • ISSUE 148 cotswoldtimes Vouchers inside on page 4, 7 & 48 PICK UP YOUR FREE COPY FOR LOCAL NEWS, COMMENT, EVENTS + FEATURES. IRRESISTIBLE Meal Deal £10 MAIN SIDE DESSERT WINE Offer valid when purchasing one MAIN + one SIDE + one SIDE or DESSERT from the Irresistible Meal Deal £10 range + one bottle of WINE in a single transaction. See shelf for details. Subject to availability. Varieties as stocked. Pictures for illustration purposes only. Offers available in Co-op Chipping High Street Norton store ONLY. Varieties as stocked. All offers subject to availability while stocks last. See in-store for details. It is an offence to sell alcohol to anyone Chipping Norton under the age of 18. Alcohol only available in licensed stores. Remember to OX7 5AB drink responsibly. For information on sensible drinking and to work out how many units are in each bottle or can, visit DRINKAWARE.CO.UK Tel: 01608 642672 2 | COTSWOLD TIMES Gymnastics for all! Cotswold Clubhouse is the home of North Cotswolds Gymnastics & Trampolining Academy. A County recognised sports club, we welcome people of all ages and abilities to join. We offer a range of gymnastics and trampolining classes, for little ones up to adults. Easter Gym Holiday Camps are now available to book. Lots of activity and fun for your children! Based in Bourton on the Water @cotswoldclubhouse @ncgta For more information on all of our gymnastics classes, please visit: ncgta.co.uk Email: [email protected] Tel: 01451 263130 Forthcoming Events Mother’s Day – -

Parish Register Guide L

Lancaut (or Lancault) ...........................................................................................................................................................................3 Lasborough (St Mary) ...........................................................................................................................................................................5 Lassington (St Oswald) ........................................................................................................................................................................7 Lea (St John the Baptist) ......................................................................................................................................................................9 Lechlade (St Lawrence) ..................................................................................................................................................................... 11 Leckhampton, St Peter ....................................................................................................................................................................... 13 Leckhampton (St Philip and St James) .............................................................................................................................................. 15 Leigh (St Catherine) ........................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Leighterton ........................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Chastleton House Was Closed Today,The Four Shire Stone

Chastleton House was closed today Secret Cottage took a Cotswolds tour to Chastleton House today, but unfortunately it was closed for the filming of Wolf Hall and Bringing up the Bodies. Filming started yesterday and will continue until August the 6th. As an alternative, we took our tourists to The Rollright Stones which were nearby and our guests thoroughly enjoyed themselves. However, we wanted to tell you something about the fabulous Chastleton House. Chastleton House is a fine Jacobean country house built between 1607 and 1612 by a Welsh wool merchant called Walter Jones. The house is built from beautiful local Cotswold stone and is Grade I listed. It was built on the site of an older house by Robert Catesby who masterminded the gunpowder plot! There are many unique features to Chastleton House; one of them being the longevity of the property within one family. In fact, until the National Trust took over the property in 1991, it had remained in the same family for around 400 years. Unlike many tourist attractions, the National Trust have kept this house completely unspoilt – they are conserving it, rather than restoring it. They don’t even have a shop or tea room; giving you the opportunity to truly step back in time. It’s almost like being in a living museum with a large number of the rooms open to the public that are still beautiful and untouched and have escaped the intrusion of being bought into the 21st century. A trip to Chastleton House brings history to life. This house has charm; there is no pretence with making walls perfect or fixing minor problems; expect to find gaps in the walls, cracks in the ceiling, uneven floors, dust and cobwebs in all their glory. -

Warmer Days and Longer Evenings

StowTimes_May09.qxd 27/4/09 15:30 Page 1 STOW TIMES Issue 64 • May 2009 An independent paper delivered to homes & businesses in Stow-on-the-Wold, Broadwell, Adlestrop, Oddington, Bledington, Icomb, Church Westcote, Nether Westcote, Wyck & Little Rissington, Maugersbury, Nether Swell, Lower & Upper Swell, Naunton, Donnington, Condicote, Naunton, Longborough and Temple Guiting Extra copies of Stow Times are generally available in Stow Visitor Information Centre and Stow Library. Warmer days and longer evenings... And there’s LOTS going on Climate Change & energy efficient houses Exhibitions, concerts, fetes & The Prof on the Four Shire Stone festivals, open gardens, glorious walks and Ben Eddols with something for the weekend! record-breaking picnics! Is this the worst best place... Join in! With Local Sport, Clubs and Cinemas – this is your May edition! Photo of bluebell woods kindly provided by James Minter, Chair of the North Cotswolds Digital Camera Club www.ncdcc.co.uk StowTimes_May09.qxd 27/4/09 15:30 Page 2 MAY EVENTS 27th April ~ 2nd May : Fosse Manor Fish Week 4th ~ 30th May : Asparagus Season 10th May : Jazz Sunday Lunch 14th May : Ladies Lunch Club £14.00 per person 28th May : Ladies Lunch Club trip to Abbey Gardens and the Old Bell Hotel in Malmesbury Please telephone for details - booking essential LOOK OUT FOR JUNE EVENTS Website: www.thekingsarmsstow.co.uk Email: [email protected] Telephone: (01451) 830364 AWARD WINNING NASEBY RESTAURANT MAY SPECIAL OFFERS GREAT STAFF AND SERVICE TWO COURSE SET MENU £12 REAL ALES & FINE WINES THREE COURSE SET MENU £15 LOCALS ALWAYS WELCOME! ROOMS FROM £79 B&B BOOK NOW 2 StowTimes_May09.qxd 27/4/09 15:30 Page 3 STOW TIMES From the Editor Inside this edition First, I must say Thank You. -

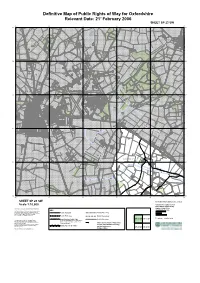

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21St February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 23 SW

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21st February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 23 SW 20 21 22 23 24 25 0006 1200 2400 5500 3800 0004 0800 2500 3400 4600 8400 2900 8500 5100 0006 6300 7800 0004 0004 2000 7700 35 A 429 35 0890 9377 0078 0078 1476 4074 0074 7975 8673 Brook Hill Lower Farm 3373 Barn Lower Farm Mount Sorrell 0070 5868 Pumping Station 0066 5664 Brook Cottages 9465 8363 0158 7259 The Green 1856 Ash House 4754 Farm 0055 5251 0052 St Leonard's Church 2053 9754 0053 0053 0153 Lower Lemington Parsonage 8447 Farm 7649 3247 8949 7445 Vicarage 0045 The Leys 2643 Manor Farm Fox and 9144 Hounds 6040 6840 Ingram Close 3839 7440 Hillside Farm 0035 8635 4434 6432 Woodhills 1730 Farm 8128 A 429 4326 2025 0624 0020 A 429 8425 0022 0923 8720 Badgers Oak Farm 0022 0020 5315 6315 7417 Lemington Manor 5607 1100 A 429 1500 3600 6700 8600 1300 3800 5900 0900 5400 6800 0005 New 0002 2400 5000 6400 0001 1300 2800 7600 8800 9700 0005 3700 0001 5000 Farm 7900 0012 A 429 0900 6700 New 8600 2400 5000 6500 7600 4300 Farm 6800 0005 1300 3800 5900 0002 0005 3700 6400 0001 2800 34 8800 34 Old Farm 3700 7500 8400 0096 Dorn Priory 4989 0086 5586 0085 9383 4780 0979 Lemington Grange 5278 3378 7278 0676 2075 2973 6573 0070 0070 4969 7268 0568 2966 0666 5265 0065 0065 Upper Woodhills Farm NORTH CIRCULAR ROAD 9963 3862 4363 3160 8355 6TH AVENUE 0555 0054 5954 4953 3952 3950 8649 8946 8046 7445 Dorn Heath Farm 0042 0042 0039 9838 9835 5TH AVENUE Fire Service D AVENUE 6531 2N 8132 Technical College 5933 5931 1730 6TH AVENUE 2521 2121 9519 -

SUMMER 2020 NEWS the Steps to Nature's Recovery Oxfordshire 2050 Plan and Nature Recovery Networks

people and nature - making connections SUMMER 2020 NEWS The steps to nature's recovery Oxfordshire 2050 Plan and Nature Recovery Networks Imagine a birds-eye view over the the River Thames and its tributaries – landscape-scale conservation. The Oxfordshire landscape, at the century’s passing over cranes and white storks Environment Bill currently going through halfway point. It is probably looking that have taken up residence among Parliament will require local authorities more wooded, and there are more groups of Exmoor ponies and English to map their local networks and prepare houses and more wind turbines. Electric longhorn cattle. Maybe bluebells have recovery strategies. Following last cars and trucks are quietly trundling spread out from the year’s ‘Colchester along the roads. But will there be more last surviving patches Declaration’, Areas of wildlife? of ancient forest into For a positive future vision Outstanding Natural Envisioning this future, perhaps naturally regenerating “ of a nature-rich landscape Beauty (AONBs) have you can make out a succession of woodlands. And people to start taking shape, action made a commitment are out and about beaver dams along the many streams to reverse the long-term loss to do likewise that are now flanked by the alders and enjoying natural parks (landscapesforlife.org.uk). willows planted in the 2020s to help with thriving wildlife, of nature will be needed So, there is now slow floodwaters? Curlews may be just a short walk from significant momentum flying over floodplain grasslands beside