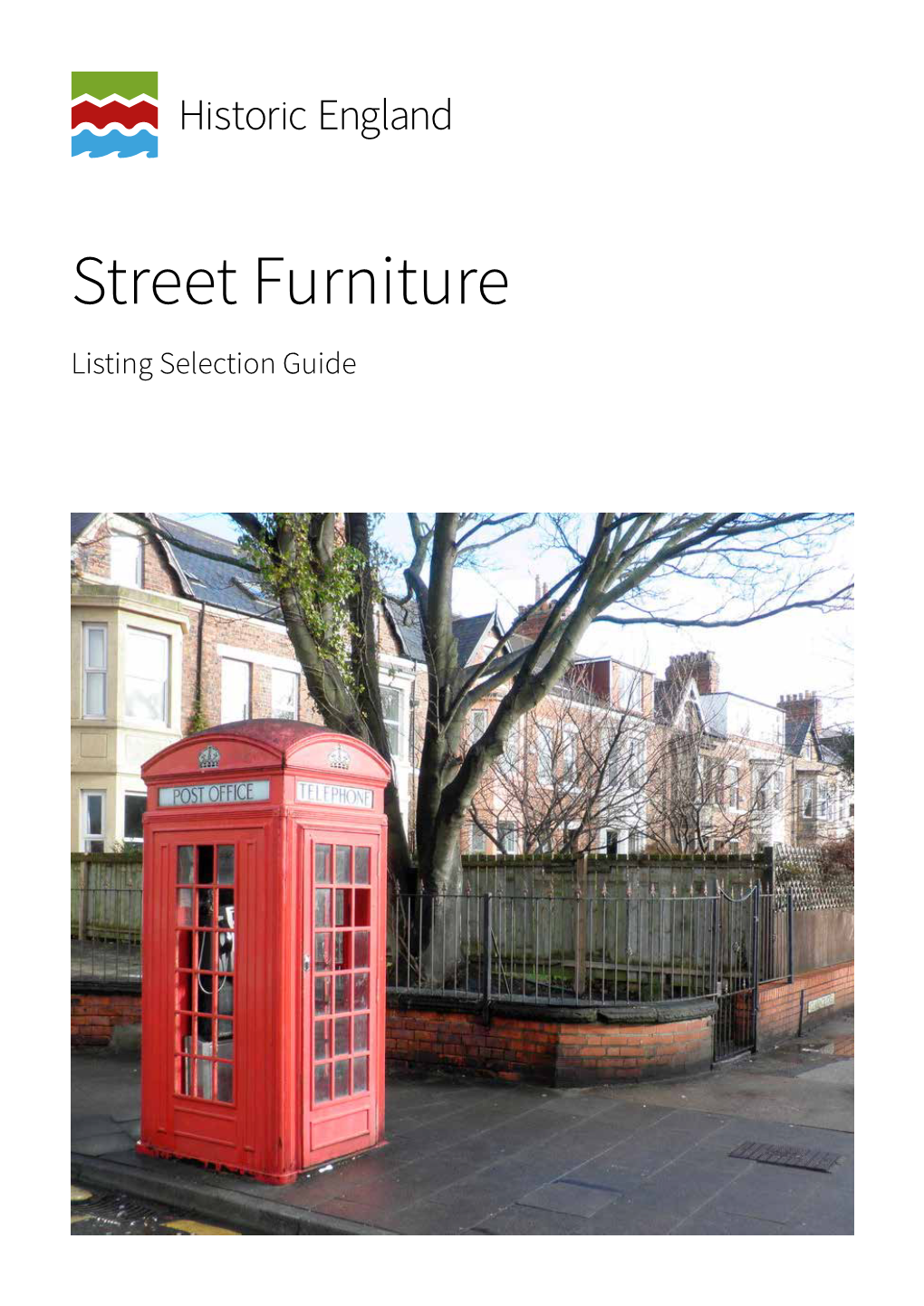

Street Furniture Listing Selection Guide Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Reference Document

2012 REFERENCE DOCUMENT Incorporation by reference In accordance with Article 28 of EU Regulation n°809/2004 dated 29 April 2004, the reader is referred to previous “Documents de référence” containing certain information: 1. Relating to fiscal year 2011: - The Management Discussion and Analysis and consolidated financial statements, including the statutory auditors’ report, set forth in the “Document de référence” filed on 23 April 2012 under number D.12-0387 (pages 59 to 124 and 216, respectively). - The corporate financial statements of JCDecaux SA, their analysis, including the statutory auditors’ report, set forth in the “Document de référence” filed on 23 April 2012 under number D.12-0387 (pages 125 to 148 and 218, respectively). - The statutory auditors’ special report on regulated agreements with certain related parties, set forth in the “Document de référence” filed on 23 April 2012 under number D.12-0387 (page 220). 2. Relating to fiscal year 2010: - The Management Discussion and Analysis and consolidated financial statements, including the statutory auditors’ report, set forth in the “Document de référence” filed on 14 April 2011 under number D.11-0300 (pages 55 to 122 and 222 to 223, respectively). - The corporate financial statements of JCDecaux SA, their analysis, including the statutory auditors’ report, set forth in the “Document de référence” filed on 16 April 2010 under number D.11-0300 (pages 123 to 145 and 224 to 225, respectively). - The statutory auditors’ special report on regulated agreements with certain related parties, set forth in the “Document de référence” filed on 16 April 2010 under number D.11-0300 (pages 226 to 228). -

Active Transportation

Tuesday, September 10 & Wednesday, September 11 9:00 am – 12:00 pm WalkShops are fully included with registration, with no additional charges. Due to popular demand, we ask that attendees only sign-up for one cycling tour throughout the duration of the conference. Active Transportation If You Build (Parking) They Will Come: Bicycle Parking in Toronto Providing safe, accessible, and convenient bicycle parking is an essential part of any city's effort to support increased bicycle use. This tour will use Toronto's downtown core as a setting to explore best practices in bicycle parking design and management, while visiting several major destinations and cycling hotspots in the area. Starting at City Hall, we will visit secure indoor bicycle parking, on-street bike corrals, Union Station's off-street bike racks, the Bike Share Toronto system, and also provide a history of Toronto's iconic post and ring bike racks. Lead: Jesse Demb & David Tomlinson, City of Toronto Transportation Services Mode: Cycling Accessibility: Moderate cycling, uneven surfaces Building Out a Downtown Bike Network Gain firsthand knowledge of Toronto's on-street cycling infrastructure while learning directly from people that helped implement it. Ride through downtown's unique neighborhoods with staff from the City's Cycling Infrastructure and Programs Unit as well as advocates from Cycle Toronto as they discuss the challenges and opportunities faced when designing and building new biking infrastructure. The tour will take participants to multiple destinations downtown, including the Richmond and Adelaide Street cycle tracks, which have become the highest volume cycling facilities in Toronto since being originally installed as a pilot project in 2014. -

Jcdecaux Wins World's Second Largest Automatic Public Toilet

JCDecaux wins World’s second largest Automatic Public Toilet contract in Berlin Paris, June 28th, 2018 – JCDecaux SA (Euronext Paris: DEC), the number one outdoor advertising company worldwide and the pioneer of self-cleaning public toilets is pleased to announce that its German subsidiary Wall GmH has won the Berlin tender for the supply, installation and operation of public toilets in the German capital. Wall has operated the public toilets financed by OOH advertising revenues in Berlin since 1992. The new 15-year contract (including a 2-year extension option) was signed on Tuesday and will commence on 1/01/2019. Wall will supply, install and operate 193 new fully automatic public toilets and become responsible for the operation of 37 existing toilet facilities. Furthermore, Berlin will have the option to order 109 additional automatic public toilets and include 30 more existing toilet facilities. Wall will receive over 15 years €235,9mio from Berlin if all options are exercised. Jean-François Decaux, Co-CEO of JCDecaux, said: “After renewing earlier this year the main OOH Berlin advertising contract, we are very pleased to continue to operate the World’s second largest automatic public toilet contract which will be financed by a guaranteed fee from the City. JCDecaux also operates the World’s largest automatic public toilet contract in Paris. Our non-advertising revenues in our street furniture division represent 10% of all street furniture revenues and are very stable. This decision confirms JCDecaux’s strong ability to win street -

NCHRP Report 612 – Safe and Aesthetic Design of Urban

NATIONAL COOPERATIVE HIGHWAY RESEARCH NCHRP PROGRAM REPORT 612 Safe and Aesthetic Design of Urban Roadside Treatments TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2008 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE* OFFICERS CHAIR: Debra L. Miller, Secretary, Kansas DOT, Topeka VICE CHAIR: Adib K. Kanafani, Cahill Professor of Civil Engineering, University of California, Berkeley EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Robert E. Skinner, Jr., Transportation Research Board MEMBERS J. Barry Barker, Executive Director, Transit Authority of River City, Louisville, KY Allen D. Biehler, Secretary, Pennsylvania DOT, Harrisburg John D. Bowe, President, Americas Region, APL Limited, Oakland, CA Larry L. Brown, Sr., Executive Director, Mississippi DOT, Jackson Deborah H. Butler, Executive Vice President, Planning, and CIO, Norfolk Southern Corporation, Norfolk, VA William A.V. Clark, Professor, Department of Geography, University of California, Los Angeles David S. Ekern, Commissioner, Virginia DOT, Richmond Nicholas J. Garber, Henry L. Kinnier Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Virginia, Charlottesville Jeffrey W. Hamiel, Executive Director, Metropolitan Airports Commission, Minneapolis, MN Edward A. (Ned) Helme, President, Center for Clean Air Policy, Washington, DC Will Kempton, Director, California DOT, Sacramento Susan Martinovich, Director, Nevada DOT, Carson City Michael D. Meyer, Professor, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta Michael R. Morris, Director of Transportation, North Central Texas Council of Governments, Arlington Neil J. Pedersen, Administrator, Maryland State Highway Administration, Baltimore Pete K. Rahn, Director, Missouri DOT, Jefferson City Sandra Rosenbloom, Professor of Planning, University of Arizona, Tucson Tracy L. Rosser, Vice President, Corporate Traffic, Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., Bentonville, AR Rosa Clausell Rountree, Executive Director, Georgia State Road and Tollway Authority, Atlanta Henry G. (Gerry) Schwartz, Jr., Chairman (retired), Jacobs/Sverdrup Civil, Inc., St. -

IF P 25 MIIBHIIN I MARSH IHIIIIBESTERSIIIIIE

Reprinted from: Gloucestershire Society for Industrial Archaeology Journal for 1977-78 pages 25-29 INDUSTRIAL ABIZIIIEIILIIGY (IF p 25 MIIBHIIN I MARSH IHIIIIBESTERSIIIIIE BIIY STIPLETUN © ANCIENT ROADS An ancient way, associated with the Jurassic Way, entered the county at the Four Shire Stone (SP 231321). It came from the Rollright Stones in Oxfordshire and followed the slight ridge of the watershed between the Thames and the Severn just north of Moreton in Marsh. Its course from the Four Shire Stone is probably marked by the short stretch of county boundary across Uolford Heath to Lemington Lane. The subsequent line is diffi- cult to determine; it may have struck north west across Batsford Heath to Dorn or, perhaps more likely, may have continued along Lemington Lane around the eastern boundary of the Fire Service Technical College, so skirting the marshy area of Lemington and Batsford Heaths. In the latter case, it would have continued across the Moreton in Marsh-Todenham road and along the narrow lane past Lower Lemington which crosses the Ah29 road (the Fosse Way) to Dorn. From there it would have continued to follow approximately the line of this road up past Batsford and along the ridge above to the course followed by the Ahh, thence following the Cotswold Edge southwards. The Salt Hay from Droitwich through Campden followed the same route through Batsford and Dorn to the Four Shire Stone, where it divided into two routes. One followed the same line as the previous way through Kitebrook and past Salterls Hell Farm near Little Compton to the Ridgeway near the Rollright Stones. -

Installation of 8 Automated Public Toilets

A10 CITY OF VANCOUVER ADMINISTRATIVE REPORT Report Date: August 29, 2006 Author: Grant Woff Phone No.: 604.871.6966 RTS No.: 05923 VanRIMS No.: 13-4700-11 Meeting Date: September 12, 2006 TO: Vancouver City Council FROM: General Manager of Engineering Services SUBJECT: Installation of 8 Automated Public Toilets RECOMMENDATION A. THAT Automated Public Toilets be installed at the locations outlined in this report, and that the Park Board be requested to approve installation of an Automated Public Toilet on Pigeon Park. B. THAT TransLink again be requested to provide publicly accessible toilet facilities at all major transit terminals. C. THAT additional funding of $180,000 for utility connections to the 8 Automated Public Toilets be provided from increased revenue from the 2006 Street Furniture Program. COUNCIL POLICY There is no applicable Council Policy. SUMMARY The City has ordered 8 Automated Public Toilets (APTs) to be supplied by CBS Decaux (previously Viacom/JCDecaux) under the Street Furniture contract. Locations for these toilets have been selected to maximise usefulness, while minimising impacts on adjacent development. Installation of Automated Public Toilets 2 PURPOSE To obtain Council approval of sites for the installation of 8 Automated Public Toilets (6 small, 2 large). BACKGROUND The City is currently in the third year of a 20 year contract with CBS Decaux to implement a co-ordinated suite of street furniture. Under this contract CBS Decaux provide, install, service and maintain a number of elements, including bus shelters, litter containers, benches, bike racks, and Automated Public Toilets. This furniture is provided at no cost to the City (in fact the City receives a revenue stream), and CBS Decaux provide the furniture in return for the exclusive right to sell advertising space on designated street furniture. -

What Are the Red Phone Boxes Being Used for Now?

What is happening in the news this week? Thousands more traditional red telephone boxes are to be revived by local communities and could be transformed into museums, libraries and homes for defibrillators. Have you ever been in a telephone box? Learn more about this week’s story here. Watch this week’s useful video here. This week’s Virtual Assembly here. How does it make me feel? sad angry happy confused excited worried shocked afraid despondent aggrieved beaming addled animated agitated astonished alarmed disconsolate annoyed buoyant baffled elevated anxious astounded apprehensive dismal discontented cheery bemused enlivened apprehensive disconcerted daunted doleful disgruntled contented bewildered enthusiastic concerned distressed fearful downhearted distressed delighted disorientated exhilarated disquieted dumbfounded frantic forlorn exasperated enraptured indistinct exuberant distraught horrified horrified gloomy frustrated gleeful muddled thrilled distressed staggered petrified melancholic indignant glowing mystified disturbed startled terrified miserable offended joyful perplexed fretful stunned woeful outraged puzzled perturbed surprised wretched resentful troubled vexed uneasy Assembly Resource Read through the information below about phone boxes and some of the ways they have been revived and given a new use. Which ideas do you like the most? What are the red phone boxes? They are telephone kiosks for public telephones designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott. The red boxes are a familiar sight on the streets of the United Kingdom, Malta, Bermuda and Gibraltar. The red phone box is often seen as a British cultural icon throughout the world. Due to the huge increase of people having their own mobile phones, many of the red phone boxes are no longer being used for telephone calls. -

Protective Street Furniture PAS 68 / IWA 14

www.marshalls.co.uk/pas68 Uniclass EPIC L811 Q12 CI/Sfb (90.7) X Protective Street Furniture PAS 68 / IWA 14 Protective Street Furniture Street Furniture Protective Street Furniture Street Protective Furniture Street Contents Protective Street Furniture 03 Our Portfolio 04 Future Spaces 07 RhinoGuard™ 15/30 Protective Bollard 09 RhinoGuard™ 25/40 Protective Bollard 10 RhinoGuard™ 75/40 Protective Bollard 11 RhinoGuard™ 72/50 Protective Bollard 12 RhinoGuard™ 75/50 Protective Bollard 13 RhinoGuard™ 75/30 Protective Bollard 14 Igneo 75/40 Protective Seat 15 EOS 75/30 Protective Seat 16 RhinoBlok™ 72/40 Protective Seat 17 GEO Coordinated Range 18 Protective Planters with RhinoGuard™ Integrated Technology 19 Furniture Street Marshalls has been manufacturing hard landscaping materials for over 120 years Case Study: BAM Construction 21 and has become the leading supplier of the Case Study: Land Securities 22 products that create our urban environment. Marshalls Bespoke Product Solutions 23 Marshalls products are used nationwide by customers who are seeking reliable, high quality goods and services. Whether it’s innovative paving, sustainable drainage systems or street furniture, Marshalls 360 – Designed around you 24 Marshalls is a brand that businesses can trust. Indeed Marshalls has earned the status of Superbrand for seven consecutive years, an award bestowed only upon the most reputable, most influential brands in their field. www.marshalls.co.uk/pas68 We believe it is all a consequence of our passion to create Our Protective Street Furniture products are manufactured in line with PAS / IWA legislation better, safer spaces. 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010 2 Protective Street Furniture Street Furniture Protective Street Furniture Street Protective Furniture Street Protective Street Furniture is not The usage and requirements for protective street furniture traditionally viewed as a product to enhance products can be broken down into three key areas: the landscape, more as a necessary evil to 1. -

Chastleton House Was Closed Today,The Four Shire Stone

Chastleton House was closed today Secret Cottage took a Cotswolds tour to Chastleton House today, but unfortunately it was closed for the filming of Wolf Hall and Bringing up the Bodies. Filming started yesterday and will continue until August the 6th. As an alternative, we took our tourists to The Rollright Stones which were nearby and our guests thoroughly enjoyed themselves. However, we wanted to tell you something about the fabulous Chastleton House. Chastleton House is a fine Jacobean country house built between 1607 and 1612 by a Welsh wool merchant called Walter Jones. The house is built from beautiful local Cotswold stone and is Grade I listed. It was built on the site of an older house by Robert Catesby who masterminded the gunpowder plot! There are many unique features to Chastleton House; one of them being the longevity of the property within one family. In fact, until the National Trust took over the property in 1991, it had remained in the same family for around 400 years. Unlike many tourist attractions, the National Trust have kept this house completely unspoilt – they are conserving it, rather than restoring it. They don’t even have a shop or tea room; giving you the opportunity to truly step back in time. It’s almost like being in a living museum with a large number of the rooms open to the public that are still beautiful and untouched and have escaped the intrusion of being bought into the 21st century. A trip to Chastleton House brings history to life. This house has charm; there is no pretence with making walls perfect or fixing minor problems; expect to find gaps in the walls, cracks in the ceiling, uneven floors, dust and cobwebs in all their glory. -

A HISTORY of LONDON in 100 PLACES

A HISTORY of LONDON in 100 PLACES DAVID LONG ONEWORLD A Oneworld Book First published in North America, Great Britain & Austalia by Oneworld Publications 2014 Copyright © David Long 2014 The moral right of David Long to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved Copyright under Berne Convention A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-78074-413-1 ISBN 978-1-78074-414-8 (eBook) Text designed and typeset by Tetragon Publishing Printed and bound by CPI Mackays, Croydon, UK Oneworld Publications 10 Bloomsbury Street London WC1B 3SR England CONTENTS Introduction xiii Chapter 1: Roman Londinium 1 1. London Wall City of London, EC3 2 2. First-century Wharf City of London, EC3 5 3. Roman Barge City of London, EC4 7 4. Temple of Mithras City of London, EC4 9 5. Amphitheatre City of London, EC2 11 6. Mosaic Pavement City of London, EC3 13 7. London’s Last Roman Citizen 14 Trafalgar Square, WC2 Chapter 2: Saxon Lundenwic 17 8. Saxon Arch City of London, EC3 18 9. Fish Trap Lambeth, SW8 20 10. Grim’s Dyke Harrow Weald, HA3 22 11. Burial Mounds Greenwich Park, SE10 23 12. Crucifixion Scene Stepney, E1 25 13. ‘Grave of a Princess’ Covent Garden, WC2 26 14. Queenhithe City of London, EC3 28 Chapter 3: Norman London 31 15. The White Tower Tower of London, EC3 32 16. Thomas à Becket’s Birthplace City of London, EC2 36 17. -

Section 2 – Core Area 2.6 Street Furnishings Palette Overview

Section 2 – Core Area 2.6 Street Furnishings Palette Overview The Downtown Station Area Specific Plan (Specific Plan) includes Street- scape Guidelines that apply to key streets within the Specific Plan area. These streets are identified as playing a larger roll in the daily functioning and traffic patterns of the area. One of the Streetscape Guidelines calls for development of a Street Furnishings Palette. The Specific Plan defines a “palette” as a group of predetermined specifications that will be applied along individual corridors or in individual sub-areas within the Specific Plan area. The Street Furnishings Palette will provide guidance for street furni- ture purchases in association with new development and capital improvement projects, and for purchases made by both the public and private sectors. The Specific Plan includes seven unique sub-areas within approximately 1/2 mile of the Sonoma Marin Area Rail Transit (SMART) station site in Rail- road Square. This section of the Design Guidelines will address two of the seven sub-areas: Railroad Square and Courthouse Square. It should be noted that the boundaries of the Street Furnishing Palette extend beyond the Specific Plan boundaries, down 4th Street, east, to Brookwood Avenue (see map on page 2.6.2). The City of Santa Rosa is intent on maintaining and reinforcing the unique character of each sub-area within the Specific Plan boundaries. Providing an appropriate variety of attractive and complementary street furniture within each sub-area is considered necessary to achieving this goal. The Railroad Square and Courthouse Square sub-areas are the primary downtown com- mercial areas and share many characteristics, although each has its own dis- tinct character that should be reflected in and celebrated by its respective street furnishings. -

Telecommunications Provider Locator

Telecommunications Provider Locator Industry Analysis & Technology Division Wireline Competition Bureau January 2010 This report is available for reference in the FCC’s Information Center at 445 12th Street, S.W., Courtyard Level. Copies may be purchased by contacting Best Copy and Printing, Inc., Portals II, 445 12th Street S.W., Room CY-B402, Washington, D.C. 20554, telephone 800-378-3160, facsimile 202-488-5563, or via e-mail at [email protected]. This report can be downloaded and interactively searched on the Wireline Competition Bureau Statistical Reports Internet site located at www.fcc.gov/wcb/iatd/locator.html. Telecommunications Provider Locator This report lists the contact information, primary telecommunications business and service(s) offered by 6,493 telecommunications providers. The last report was released March 13, 2009.1 The information in this report is drawn from providers’ Telecommunications Reporting Worksheets (FCC Form 499-A). It can be used by customers to identify and locate telecommunications providers, by telecommunications providers to identify and locate others in the industry, and by equipment vendors to identify potential customers. Virtually all providers of telecommunications must file FCC Form 499-A each year.2 These forms are not filed with the FCC but rather with the Universal Service Administrative Company (USAC), which serves as the data collection agent. The pool of filers contained in this edition consists of companies that operated and collected revenue during 2007, as well as new companies that file the form to fulfill the Commission’s registration requirement.3 Information from filings received by USAC after October 13, 2008, and from filings that were incomplete has been excluded from this report.