Ÿþ1 6 F I R S T a M E N D . L . R E V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lessons on Political Speech, Academic Freedom, and University Governance from the New North Carolina

LESSONS ON POLITICAL SPEECH, ACADEMIC FREEDOM, AND UNIVERSITY GOVERNANCE FROM THE NEW NORTH CAROLINA * Gene Nichol Things don’t always turn out the way we anticipate. Almost two decades ago, I came to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) after a long stint as dean of the law school in Boulder, Colorado. I was enthusiastic about UNC for two reasons. First, I’m a southerner by blood, culture, and temperament. And, for a lot of us, the state of North Carolina had long been regarded as a leading edge, perhaps the leading edge, of progressivism in the American South. To be sure, Carolina’s progressive habits were often timid and halting, and usually exceedingly modest.1 Still, the Tar Heel State was decidedly not to be confused with Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, or my home country, Texas. Frank Porter Graham, Terry Sanford, Bill Friday, Ella Baker, and Julius Chambers had cast a long and ennobling shadow. Second, I have a thing for the University of North Carolina itself. Quite intentionally, I’ve spent my entire academic career–as student, professor, dean, and president–at public universities. I have nothing against the privates. But it has always seemed to me that the crucial democratizing aspirations of higher education in the United States are played out, almost fully, in our great and often ambitious state institutions. And though they have their challenges, the mission of public higher education is a near-perfect one: to bring the illumination and opportunity offered by the lamp of learning to all. Black and white, male and female, rich and poor, rural and urban, high and low, newly arrived and ancient pedigreed–all can, the theory goes, deploy education’s prospects to make the promises of egalitarian democracy real. -

The Restoration of Tolerance

The Restoration of Tolerance Steven D. Smitht In this Article, ProfessorSmith examines the problems that inhere in a value-neutral version of liberalism. He argues that because governing necessarily entails choosing among competing visions of what is good or worthy ofprotection, neutrality is an empty ideal that is incapable of sup- porting a liberal community. Professor Smith therefore rejects the asser- tion that a society must choose between intolerance and neutrality. He argues instead that society's real choice is between tolerance and intoler- ance. He concludes that tolerance, which attempts to give proper respect and scope to the claims of both political community and individualfree- dom, is the only reasonablealternative to intolerance. He then uses recent free exercise of religion andfree speech cases to show how a theory of toler- ance might affect judicial doctrine. Tolerance is a very dull virtue. It is boring. Unlike love, it has always had a bad press. It is negative. It merely means putting up with people, being able to stand things. No one has ever written an ode to tolerance, or raised a statue to her. Yet this is the quality which will be most needed .... -E.M. Forster1 The current crisis in liberal democratic thought has led to a revival of interest in the concept of tolerance.2 Although it has never wholly disappeared from liberal diction, "tolerance," like "patriotism," "higher t Professor of Law, University of Colorado. B.A., Brigham Young University, 1976; J.D. Yale University, 1979. I thank Richard Collins, Frederick Gedicks, Kerry Macintosh, Chris Mueller, Gene Nichol, Pierre Schlag, and the students in my jurisprudence class for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article. -

School of Law

The Magazine of North Carolina Central University School of Law Building on the Legacy Producing Practice-Ready Attorneys Stories from the Practice Front: Civil, Criminal, Bankruptcy, Tax, and Dispute Resolution Our Students at the Supreme Court First Legal Eagle Commencement Reunion North Carolina Central University Volume 15 school of law of Counsel is a magazine for alumni and friends of North Carolina Central University School of Law. Volume 15 / Spring 2013 ofCOUNSEL of Counsel is published by the NCCU Table of Contents School of Law for alumni, friends, and members of the law community. Dean Phyliss Craig-Taylor Former Director of Development Legal Eagle Alumni Awards Delores James Editor Shawnda M. Brown Readings and Features Also In This Issue Copy Editors 15 Brenda Gibson ’95 04 Letter from the Dean Faculty Spotlights Rob Waters 25 05 Practice-Ready Attorneys Alumni News Design and Illustrations 28 Kompleks Creative Group 12 Susie Ruth Powell and “The Loving Story” Donor List Printer 13 Progressive Business Solutions John Britton, Charles Hamilton Houston Chair Photographers 13 Foreclosure Grant Elias Edward Brown, Jr. Tobias Rose Writers and Contributors At School Now Sharon D. Alston Carissa Burroughs 16 Supreme Court Trip Cynthia Fobert 18 Delores James Most Popular US News & World Report 18 PILO Auction 20 Graduation We welcome your comments, suggestions, and ideas for future articles or alumni news. Please send correspondence to: Alumni Events Carissa Burroughs Lorem Ipusm caption Lorem Ipusm caption 22 Dean’s Welcome Reception The NCCU School of Law NCCU School of Law Lorem Ipusm caption Lorem Ipusm caption publishes the of Counsel magazine. -

The Lemon Project: a Journey of Reconciliation Report of the First Eight Years

THE LEMON PROJECT | A Journey of Reconciliation I. SUMMARY REPORT The Lemon Project: A Journey of Reconciliation Report of the First Eight Years SUBMITTED TO Katherine A. Rowe, President Michael R. Halleran, Provost February 2019 THE LEMON PROJECT STEERING COMMITTEE Jody Allen, Stephanie Blackmon, David Brown, Kelley Deetz, Leah Glenn, Chon Glover, ex officio, Artisia Green, Susan A. Kern, Arthur Knight, Terry Meyers, Neil Norman, Sarah Thomas, Alexandra Yeumeni 1 THE LEMON PROJECT | A Journey of Reconciliation I. SUMMARY REPORT Executive Summary In 2009, the William & Mary (W&M) Board of Visitors (BOV) passed a resolution acknowledging the institution’s role as a slaveholder and proponent of Jim Crow and established the Lemon Project: A Journey of Reconciliation. What follows is a report covering the work of the Project’s first eight years. It includes a recap of the programs and events sponsored by the Lemon Project, course development, and community engagement efforts. It also begins to come to grips with the complexities of the history of the African American experience at the College. Research and Scholarship structure and staffing. Section III, the final section, consists largely of the findings of archival research and includes an Over the past eight years, faculty, staff, students, and overview of African Americans at William & Mary. community volunteers have conducted research that has provided insight into the experiences of African Americans at William & Mary. This information has been shared at Conclusion conferences, symposia, during community presentations, in As the Lemon Project wraps up its first eight years, much scholarly articles, and in the classroom. -

Entrepreneurial Spirit

502606 CU Amicus:502606 CU Amicus 12/10/08 11:35 AM Page 1 Amicus UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO LAW SCHOOL VOLUME XXIV, NUMBER 2, FALL 2008 The Entrepreneurial Spirit Inside: • $5 M Gift for Schaden Chair in Experiential Learning • Honor Roll of Donors 502606 CU Amicus:502606 CU Amicus 12/10/08 9:21 AM Page 2 Amicus AMICUS is produced by the University of Colorado Law School in conjunction with University Communications. Electronic copies of AMICUS are available at www.colorado.edu/law/alumdev. S Inquiries regarding content contained herein may be addressed to: la Elisa Dalton La Director of Communications and Alumni Relations S Colorado Law School 401 UCB Ex Boulder, CO 80309 Pa 303-492-3124 [email protected] Writing and editing: Kenna Bruner, Leah Carlson (’09), Elisa Dalton Design and production: Mike Campbell and Amy Miller Photography: Glenn Asakawa, Casey A. Cass, Elisa Dalton Project management: Kimberly Warner The University of Colorado does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national ori- gin, sex, age, disability, creed, religion, sexual orientation, or veteran status in admission and access to, and treatment and employment in, its educational programs and activities. 502606 CU Amicus:502606 CU Amicus 12/8/08 11:02 AM Page 3 2 FROM THE DEAN The Entrepreneurial Spirit 3 ENTREPRENEURS LEADING THE WAY Alumni Ventures Outside the Legal Profession 15 FACULTY EDITORIAL CEO Pay at a Time of Crisis 16 LAW SCHOOL NEWS $5M Gift for Schaden Chair 16 How Does Colorado Law Compare? 19 Academic Partnerships 20 21 LAW SCHOOL EVENTS Keeping Pace and Addressing Issues 21 Serving Diverse Communities 22 25 FACULTY HIGHLIGHTS Teaching Away from Colorado Law 25 Speaking Out 26 Schadens present Books 28 largest gift in Colorado Board Appointments 29 Law history — the Schaden Chair in 31 HONOR ROLL Experiential Learning. -

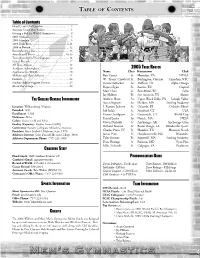

2005 TRIBE ROSTER Application to W&M

TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Head Coach Cliff Gauthier .................................... 2 Assistant Coach Pete Walker ................................... 3 Getting a Feel for W&M Gymnastics ..................... 4 2005 Outlook ........................................................ 5 2005 Schedule ........................................................ 5 2005 Team Bios .................................................6-11 2004 in Review .................................................... 12 Remembering a Hero ........................................... 13 Awards and Honors .........................................14-15 Team Awards/All-Time Captains .......................... 16 School Records ..................................................... 17 All-Time Alumni .................................................. 18 Academic Athmosphere ........................................ 19 2005 TRIBE ROSTER Application to W&M ........................................... 20 Name Class Hometown Club William and Mary Athletics ................................. 21 Ben Carter Sr. Herndon, VA NVGA Facilities ............................................................... 22 W. “Sloan” Crawford Fr. Burlington, Ontario Canadian NTC Student-Athlete Support Services ......................... 23 Devin DeBacker So. Staff ord, TX Alpha Omega About the College ................................................ 24 Rupert Egan Sr. Austin, TX Capital Matt Elson Sr. Brookfi eld, WI Salto Jay Hilbun Fr. San Antonio, TX Alamo THE COLLEGE GENERAL INFORMATION -

The Virginia Informer Chris Davis, Design Editor Mission Statement Mike Crump • Sam Mcvane • Kelsey Powell CSU 7056, P.O

Chris Adkins chats with The Informer - Page 5 The need for speed... reading - Page 8 Volume 3 An independent The Virginia publication at the College Issue 7 of William and Mary. January 30, 2008 The common sense paper Established 2005 Informer of record on campus. www.VAInformer.com Life on the campaign trail Funding the Sex Workers’ Art Show Behind the money and politics Nick Fitzgerald Executive Editor he Sex Workers’Art Show (SWAS) has been a controversial topic on campus over Tthe past three years. The controversy has sparked discussions in a variety of media, including newspaper columns, Facebook groups and through Exclusive conversations both behind closed doors and in the proverbial public square. nationwide Amidst the conversation, however, people on both sides seem uninformed regarding the details of how coverage of SWAS actually comes to campus to perform. There presidential race are monetary, budgetary and political considerations involved in bringing such an event to William and Mary. To understand the student-administered budget Pages 6 and 7 process and its politics is to have a better understanding of how and why the show has been approved for a third consecutive year. The Board of Visitors approves all university funding, which includes the student affairs budget. Within that budget is a breakdown of student activities fees, which are mandatory. The fee is set by the student government; it was $86 this year. The purpose of this fee is to provide funding to nearly all the independent, student-run organizations which apply for it. There are some exceptions; no money can be approved for religious devotional or partisan political activities. -

20201125 Canuel CV

ELIZABETH A. CANUEL CHANCELLOR PROFESSOR OF MARINE SCIENCE Virginia Institute of Marine Science/William & Mary Gloucester Point, VA 23062 Phone: 804-684-7134; FAX: (804-684-7786) E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D., 1992, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, Marine Sciences. B.S., 1981, Stonehill College, North Easton, MA, Chemistry. ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2018-present Chancellor Professor of Marine Science, Department of Physical Sciences, School of Marine Science, William & Mary, VA. 2018-2020 Program Director (IPA Rotator), Chemical Oceanography Program, Ocean Sciences Division, National Science Foundation. 2016-2017 Senior Research Fellow, Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, Smithsonian Institution, Edgewater MD 2013 Visiting Professor, Chemistry Department, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio). Supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico or National Research Council of Brazil (CNPq) 2006-present Professor, Department of Physical Sciences, School of Marine Science, William & Mary, VA. 2000-2006 Associate Professor, Department of Physical Sciences, School of Marine Science, William & Mary, VA. 2002-2005 Class of 1964 Term Endowed Associate Professor of Marine Science, School of Marine Science, William & Mary, VA. 1994-2000 Assistant Professor, Department of Physical Sciences, School of Marine Science, William & Mary, VA. 1992-1994 National Research Council Post-doctoral Fellow, Water Resources Division, U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA. RESEARCH INTERESTS -

Participant Biographies

UNC CENTER ON POVERTY, WORK AND OPPORTUNITY ACCESS TO JUSTICE IN NORTH CAROLINA: A RIGHT TO COUNSEL IN CIVIL CASES Participant Biographies Laura Klein Abel Laura Klein Abel is Deputy Director of the Justice Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, where she has worked since 1999. Her work is aimed at enhancing the ability of low-income families and individuals to obtain legal counsel and access to the courts, and at securing the freedom of nonprofit organizations to exercise their First Amendment rights in the course of assisting low- income communities. Prior to joining the Brennan Center, Abel was a Gibbons Fellow at Gibbons, Del Deo, Dolan, Griffinger & Vecchione, P.C. where she litigated on behalf of low-income people in a wide variety of cases. In preceding years, she was a staff attorney fellow for the ACLU Reproductive Freedom Project and clerk for Judge Robert Carter of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. Abel received her J.D. from Yale Law School in 1994. Charles Becton Now an attorney with the Raleigh law firm of Fuller, Becton, Slifkin & Bell, P.A., Charles Becton is a Fellow in the American College of Trial Lawyers, the American Board of Trial Attorneys and the International Society of Barristers. From 1981 to 1990, he was a Judge on the North Carolina Court of Appeals, and in 1985 was named North Carolina Appellate Judge of the Year. Becton was the 2008-09 president of the North Carolina Bar Association. A recipient of many trial advocacy awards, he is also the John Scott Cansler Lecturer at the University of North Carolina School of Law and a Senior Lecturer in Law at Duke University School of Law. -

Policy Practice in Field Education Initiative

policy practice in FIELD EDUCATION + SUMMARY REPORT + CHALLENGES OUTCOME IMPACT FUTURE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Contents CSWE thanks the Fund for Social Policy Education and Practice (FSPEP), which is supported by the Lois and Samuel Silberman Grant Fund of The 03 INTRODUCTION New York Community Trust, and the Casey Family Foundation for their 06 BY THE NUMBERS generous support of this initiative. 08 ICON LEGEND CSWE also thanks the grantees for their innovative work in policy field 09 SUMMARY REPORTS education. + Boston University ..................................... 9 + Bryn Mawr College ................................... 11 ADVISORY COMMITTEE + Clarke University ..................................... 14 + Colorado State University ............................. 17 + Darlyne Bailey + Concord University .................................. 20 + Rebecca Brigham + Coppin State University ............................... 22 + Darla Spence Coffey + Eastern Michigan University .......................... 24 + Eastern Washington University ....................... + Holly Delany Cole 27 + Evangel University .................................... 29 + Sam Copeland + Howard University .................................... 31 + Charles Lewis Jr. + Humboldt State University ........................... 33 + Lisa Richardson + Hunter College ........................................ 36 + Indiana University .................................... 39 + Patricia White + Michigan State University ............................ 41 + Niagara University .................................. -

Statement of Constitutional Law Scholars on the Supreme Court Vacancy

Statement of Constitutional Law Scholars on the Supreme Court Vacancy February 24, 2016 We write as constitutional law scholars to urge President Obama and the United States Senate to fulfill their constitutional duties with regard to the vacancy that exists on the Supreme Court because of the death of Justice Antonin Scalia. We do not write in support of or in opposition to any specific candidate. Rather, our position is simply that the President has the duty to nominate a candidate to fill the current Supreme Court vacancy and the Senate has the duty to “advise and consent,” which means to hold hearings and to vote on the nominee. Article II of the Constitution is explicit that the president “shall nominate . judges of the Supreme Court.” There is no exception to this provision for election years. Throughout American history, presidents have nominated individuals to fill vacancies during the last year of their terms. Likewise, the Senate’s constitutional duty to “advise and consent” – the process that has come to include hearings, committee votes, and floor votes – has no exception for election years. In fact, over the course of American history, there have been 24 instances in which presidents in the last year of a term have nominated individuals for the Supreme Court and the Senate confirmed 21 of these nominees. The Senate, of course, has discretion in the method of carrying out its constitutional duty to “advise and consent,” but for the Senate not to consider a nominee until after the next president is inaugurated would be unprecedented and would leave a vacancy that would undermine the ability of the Supreme Court to carry out its constitutional duties. -

At Home Page 24

THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL SCHOOL OF LAW CAROLINA LAW Making a Difference at Home page 24 VOLUME 37, ISSUE TWO FALL-WINTER 2013 UNC Law Alumni Association Board of Directors DEAN’S MESSAGE Executive Officers Thomas F. Taft ’72, president Craig T. Lynch ’86, vice president Dear Friends: Leslie C. Packer ’86, second vice president We spend much time at Carolina Law pondering pedagogy and John Charles Boger ’74, secretary-treasurer the future of the law, asking what we can do as educators — through Harriett J. Smalls ’99, Law Foundation chair classes, clinics, externships and extracurricular offerings — to Marion A. Cowell Jr. ’64, past campaign chair strengthen lawyers-in-training and mold them into outstanding members of the legal profession. In this issue of Carolina Law, David M. Moore II ’69, past president (2007-08) we set down the theme of future proficiency to focus on present John S. Willardson ’72, past president (2008-09) service — examining what our promising students, our energetic Norma R. Houston ’89, past president (2009-10) faculty, and our 10,000 living alumni, are doing right now to serve Ann Reed ’71, past president (2010-11) the people and institutions of the State of North Carolina. It’s a remarkable picture. In scores of ways, Carolina Law Robert A. Wicker ‘69, past president (2011-12) EXUM STEVE students reach out every day, fall, spring and summer, to assist John Charles “Jack” Boger families and individuals who have desperate, unmet legal needs. In our six law school clinics, students respond directly — even as they learn how to become Committee Chairs outstanding lawyers — by investigating consumer fraud that may have jeopardized a family’s home Advancement Committee, Walter D.