APPENDICI Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Aerospace & Defense Global Overview

Aerospace & Defense Global Overview 2017 Aerospace & Defense Market Insights General Overview | 2017 Global Reach, Local Presence 19200 Von Karman Ave, Paseo de la Reforma 2620, Member Firm in India Havenlaan 2 Avenue du Suite 340 Despacho 1404 Col. Lomas Pending Port SIS, 8854 Irvine, CA 92612 Atlas, Mexico City 11950 B-1080 Brussels janescapital.com www.zimma.com.mx www.kbcsecurities.com 8F Cowell Building 140 Unit 1907-1908 Sapyeong-daero, No. 333 Lanhua Road Deocho-gu Shanghai 201204 Seoul 06577 www.oaklins.com/hfg www.sunp.co.kr Engelbrektsplan 1 88, rue El Marrakchi Kingdom Tower, King ul. Pańska 98, Suite 83 Stockholm Quartier Hippodrome Fahad Road, 49th floor Warsaw 00-837 www.mergers.pl SE-114 34 Casablanca 20100 Riyadh 11451 www.avantus.se www.atlascapital.ma www.swicorp.com Aerospace & Defense Market Insights Country Overview | 2017 Belgium Aerospace & Defense Overview The Belgian aerospace market is primarily comprised of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) producing assemblies, sub-assemblies and components for various aircraft, and offering various maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) services. These SMEs focus on advanced, small-batch production capabilities in both metallurgy and composite materials. The overall aerospace and defense (A&D) industry has total revenues of US$3.7 billion, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.1% since 2010. The A&D industry is expected to grow at a 0.8% CAGR in the near-future, with the industry expected to reach a value of US$3.9 billion by the end of 2019. Recently, civil aerospace has been the Belgian A&D industry’s most lucrative segment, representing over 70% of the industry's total market. -

Handbookhandbook Mobile-Satellite Service (MSS) Handbook

n International Telecommunication Union Mobile-satellite service (MSS) HandbookHandbook Mobile-satellite service (MSS) Handbook *00000* Edition 2002 Printed in Switzerland Geneva, 2002 ISBN 92-61-09951-3 Radiocommunication Bureau Edition 2002 THE RADIOCOMMUNICATION SECTOR OF ITU The role of the Radiocommunication Sector is to ensure the rational, equitable, efficient and economical use of the radio-frequency spectrum by all radiocommunication services, including satellite services, and carry out studies without limit of frequency range on the basis of which Recommendations are adopted. The regulatory and policy functions of the Radiocommunication Sector are performed by World and Regional Radiocommunication Conferences and Radiocommunication Assemblies supported by Study Groups. Inquiries about radiocommunication matters Please contact: ITU Radiocommunication Bureau Place des Nations CH -1211 Geneva 20 Switzerland Telephone: +41 22 730 5800 Fax: +41 22 730 5785 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.itu.int/itu-r Placing orders for ITU publications Please note that orders cannot be taken over the telephone. They should be sent by fax or e-mail. ITU Sales and Marketing Division Place des Nations CH -1211 Geneva 20 Switzerland Telephone: +41 22 730 6141 English Telephone: +41 22 730 6142 French Telephone: +41 22 730 6143 Spanish Fax: +41 22 730 5194 Telex: 421 000 uit ch Telegram: ITU GENEVE E-mail: [email protected] The Electronic Bookshop of ITU: www.itu.int/publications ITU 2002 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, by any means whatsoever, without the prior written permission of ITU. International Telecommunication Union HandbookHandbook Mobile-satellite service (MSS) Radiocommunication Bureau Edition 2002 - iii - FOREWORD In today’s world, people have become increasingly mobile in both their work and play. -

Flugzeugentwurf / Aircraft Design SS 2011 1. Part

DEPARTMENT FAHRZEUGTECHNIK UND FLUGZEUGBAU Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dieter Scholz, MSME Flugzeugentwurf / Aircraft Design SS 2011 Date: 04.07.2011 Duration of examination: 180 minutes Last Name: First Name: Matrikelnummer.: Points: of 77 Grade: 1. Part 30 points, 60 minutes, closed books 1.1) Please translate to German. Please write clearly! Unreadable text causes substraction of points! 1. sweep 2. wing root 3. span 4. aisle 5. canard 6. anhedral 7. landing field length 8. trolley 9. landing gear 10. fuselage 11. empennage 12. aileron 1.2) Please translate to English! Please write clearly! Unreadable text causes substraction of points! 1. Dimensionierung 2. Leitwerk 3. Nutzlast 4. Sitzschiene 5. Maximale Leertankmasse 6. Fracht 7. Reibungswiderstand 8. Triebwerk 9. Küche 10. (Rumpf-)Querschnitt 11. Masseverhältnis 12. Oswald Faktor page 1 of 11 pages Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dieter Scholz, MSME Examination FE, SS 2011 1.3) Shown is the Iljuschin Il-62. Please name 4 Pros and Cons (Vor- und Nachteile) or name things that change flight operation! 1.4) An aircraft for 225 passengers is planned. How many seats abreast do you plan for? Explain your reasoning! 1.5) What is Maximum Zero Fuel Weight (Maxi male Leertankmasse)? How can you calcu late it? 1.6) Please name 5 requirements for a civil passenger aircraft that determine the design point! 1.7) Please name the equation used to calculate mMTO from payload mPL , operating weight empty m m m m ratio OE and fuel mass ratio F ! An aircraft proposal leads to OE = 0,6 and F mMTO mMTO mMTO mMTO = 0,4. -

Amateur Radio Satellites 101 an Introduction to the AMSAT “Easy Sats”

Amateur Radio Satellites 101 An introduction to the AMSAT “Easy Sats” Presented to the: Fayette County Amateur Radio Club Presented by: Joe Domaleski, KI4ASK AMSAT #41409 Date: November 21, 2019 Revision 2 [email protected] 1 The real title of this presentation How to have a QSO on a repeater that is 4 inches square, traveling 17,000 MPH 600 miles away, in outer space, with a handheld radio, running 5 watts. 2 Agenda • Why satellites? • Where are the satellites located? • What is a “hamsat”? • What are the Easy Sats? • What’s inside a hamsat? • An example pass of AO-91 • Emergency traffic via AO-92 • Basic equipment I use • An example pass of AO-92 • Here’s how to make your 1st QSO • Where the “cool kids” hang out • Some memorable QSO’s Stone Mountain Hamfest 2019 • Other satellite topics with Daryl Young, K4RGK President of NFARL & • Some general tips AMSAT Ambassador • Suggested resources 3 Why satellites? • Easy to get started • Only need a Technician license • Doesn’t require expensive gear • DX when HF conditions are poor • Science involved in tracking • Camaraderie of AMSAT community • Skill involved in making contact • Fun for kids of all ages • Adds another skill to your toolkit • Like “foxhunting” in the sky • The passes are short • The wonderment of it all • Because I couldn’t be an astronaut • It’s a lot of fun! Example QSO with K5DCC https://www.facebook.com/dennyj/videos/10157742522839570/ 4 Where are the satellites located? The Easy Sats are in LEO – 300-600 miles up Source: Steve Green (KS1G) & Paul Stoetzer (N8HM) 5 What -

Amateur Satellite Frequency Coordination Request1

Amateur Satellite Frequency Coordination Request — Page 1 AMATEUR SATELLITE FREQUENCY COORDINATION REQUEST1 1. Amateur-satellite service. Amateur stations meet the requirements of the radio regulations2, RR 1.56. and 1.57. RR 1.56 amateur service: A radiocommunication service for the purpose of self- training, intercommunication and technical investigations carried out by amateurs, that is, by duly authorized [licensed] persons [individual natural people] interested in radio technique solely with a personal aim [for themselves] and without pecuniary interest [compensation]. (NOTE: Explanatory terms in brackets are not part of the treaty text.) RR 1.57 amateur-satellite service: A radiocommunication service using space stations on earth satellites for the same purposes as those of the amateur service. Before asking for help from IARU with frequency coordination in the amateur-satellite service, make sure that your proposed operation meets the treaty requirements. NOTE: “Without pecuniary interest” means that you may accept free will donations of goods and services, that is, with nothing required in return. You may not sell services or data to anyone for any reason. Ultimately, the decision of whether the proposed operation is appropriate for the amateur- satellite service rests with your country’s administration (your national telecommunication regulator). Therefore, before sending your frequency coordination request to IARU, we suggest that you consult with your administration to determine whether the amateur-satellite service or another radiocommunication service is appropriate for your operation. 2. Self coordination. For over 100 years, amateur radio operators have maintained an effective tradition of self-regulation. Amateurs are expected to coordinate their use of frequencies. -

China Manned Space Programme

China Manned Space Programme Xiaobing Zhang Deputy Director Scientific Planning Bureau China Manned Space Agency [email protected] June 2015 58’COPUOS@Vienna China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) Page 1 Content ° Introduction to development strategy ° Achievements up to date ° China’s space station and its latest development ° International cooperation ° Conclusion China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) Page 2 Part I: Development strategy ° In 1992, the Chinese government approved the launch of China’s manned space programme ° Formulated the “three-step strategy” to implement the Programme China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) Page 3 Three-step strategy 3rd step : To construct China’s space station to accommodate long-term man-tended utilization on a large scale The 2 nd step : To launch space labs to make technological breakthrough in EVA, R&D, and accommodation of long- term man-tended utilization on a modest scale The 1 st step: To launch manned spaceships to master the basic human space technology China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) Page 4 Part II: Achievements up to date ° Unmanned spaceflight missions – SZ-1, 20 Nov 1999, 1 st unmanned spaceflight – SZ-2, 10 Jan 2001, 2 nd unmanned spaceflight SZ-1 SZ-2 – SZ-3, 25 Mar 2002, 3 rd unmanned spaceflight – SZ-4, 30 Dec 2002, 4 th unmanned spaceflight SZ-3 SZ-4 ° Achieved goals: – Laying a solid foundation for manned missions China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) Page 5 ° Manned spaceflight missions – Basic Human Spaceflights Shenzhou-5, 2003, 1 st manned spaceflight mission Shenzhou-6, 2005, 1 st multiple-crew -

Simcenter News Aerospace Edition

Siemens PLM Software Simcenter news Aerospace edition June 2018 siemens.com/simcenter Simcenter news | Aerospace © Solar Impulse | Revillard | Rezo.ch | Revillard © Solar Impulse Gliding toward a digital twin Welcome to the special aerospace Along more commercial lines, there is an edition of Simcenter News. As you know, excellent story about Airbus’ approach to the aerospace industry is enjoying an cabin comfort using the Simcenter™ STAR- innovation boom. And we are pleased CCM+™ software solution for computational to note the Simcenter™ portfolio has fluid dynamics (CFD). The team at Airbus played a significant role in helping inspire Helicopters, long-time pioneers in the innovation in aerospace design and process field of model-based systems engineering development over the years. We have tried (MBSE), shares its experience using to cover as many of our customer success Simcenter Amesim™ software. And we stories as possible in this 68-page issue, our invite you to read the story about the longest yet. For our cover story, we spoke Chinese commercial aircraft program, the Siemens PLM Software to the engineers behind the Pilatus PC-24 COMAC C919, and how Simcenter 3D is Jan Leuridan success story. The Pilatus development being used to help drive the certification Senior Vice President team not only created and certified the new process with the Chinese agency, SAACC. Simulation and Test Solutions Super Versatile Jet in record time by using a production-driven digital twin, they have Our aerospace edition wouldn’t be complete also revolutionized the aircraft development if we didn’t cover space. Airbus Space and certification process, proving that our and Defence explains how the Simcenter predictive engineering analytics vision in environmental dynamic testing solution support of digital twins has become a reality. -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

China's Strategic Modernization: Implications for the United States

CHINA’S STRATEGIC MODERNIZATION: IMPLICATIONS FOR THE UNITED STATES Mark A. Stokes September 1999 ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of the Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** Comments pertaining to this report are invited and should be forwarded to: Director, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 122 Forbes Ave., Carlisle, PA 17013-5244. Copies of this report may be obtained from the Publications and Production Office by calling commercial (717) 245-4133, FAX (717) 245-3820, or via the Internet at [email protected] ***** Selected 1993, 1994, and all later Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) monographs are available on the SSI Homepage for electronic dissemination. SSI’s Homepage address is: http://carlisle-www.army. mil/usassi/welcome.htm ***** The Strategic Studies Institute publishes a monthly e-mail newsletter to update the national security community on the research of our analysts, recent and forthcoming publications, and upcoming conferences sponsored by the Institute. Each newsletter also provides a strategic commentary by one of our research analysts. If you are interested in receiving this newsletter, please let us know by e-mail at [email protected] or by calling (717) 245-3133. ISBN 1-58487-004-4 ii CONTENTS Foreword .......................................v 1. Introduction ...................................1 2. Foundations of Strategic Modernization ............5 3. China’s Quest for Information Dominance ......... 25 4. -

A Pictorial History of Rockets

he mighty space rockets of today are the result A Pictorial Tof more than 2,000 years of invention, experi- mentation, and discovery. First by observation and inspiration and then by methodical research, the History of foundations for modern rocketry were laid. Rockets Building upon the experience of two millennia, new rockets will expand human presence in space back to the Moon and Mars. These new rockets will be versatile. They will support Earth orbital missions, such as the International Space Station, and off- world missions millions of kilometers from home. Already, travel to the stars is possible. Robotic spacecraft are on their way into interstellar space as you read this. Someday, they will be followed by human explorers. Often lost in the shadows of time, early rocket pioneers “pushed the envelope” by creating rocket- propelled devices for land, sea, air, and space. When the scientific principles governing motion were discovered, rockets graduated from toys and novelties to serious devices for commerce, war, travel, and research. This work led to many of the most amazing discoveries of our time. The vignettes that follow provide a small sampling of stories from the history of rockets. They form a rocket time line that includes critical developments and interesting sidelines. In some cases, one story leads to another, and in others, the stories are inter- esting diversions from the path. They portray the inspirations that ultimately led to us taking our first steps into outer space. NASA’s new Space Launch System (SLS), commercial launch systems, and the rockets that follow owe much of their success to the accomplishments presented here. -

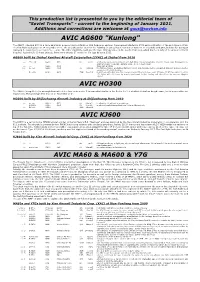

AVIC AG600 "Kunlong"

This production list is presented to you by the editorial team of "Soviet Transports" - current to the beginning of January 2021. Additions and corrections are welcome at [email protected] AVIC AG600 "Kunlong" The AG600 (Jiaolong 600) is a large amphibian powered by four Zhuzhou WJ6 turboprop engines. Development started in 2009 and construction of the prototype in 2014. The first flight took place on 24 December 2017. The aircraft can be used for fire-fighting (it can collect 12 tonnes of water in 20 seconds) and SAR, but also for transport (carrying 50 passengers over up to 5,000 km). The latter capability could give the type strategic value in the South China Sea, which has been subject to various territorial disputes. According to Chinese sources, there were already 17 orders for the type by early 2015. AG600 built by Zhuhai Yanzhou Aircraft Corporation (ZYAC) at Zhuhai from 2016 --- 'B-002A' AG600 AVIC ph. nov20 a full-scale mock-up; in white c/s with dark blue trim and grey belly, titles in Chinese only; displayed in the Jingmen Aviator Town (N30.984289 E112.087750), seen nov20 --- --- AG600 AVIC static test airframe 001 no reg AG600 AVIC r/o 23jul16 the first prototype; production started in 2014, mid-fuselage section completed 29dec14 and nose section completed 17mar15; in primer B-002A AG600 AVIC ZUH 30oct16 in white c/s with dark blue trim and grey belly, titles in Chinese only; f/f 24dec17; f/f from water 20oct18; 172 flights with 308 hours by may20; performed its first landing and take-off on the sea near Qingdao 26jul20 AVIC HO300 The HO300 (Seagull 300) is an amphibian with either four or six seats. -

OUTER SPACE TREATY Tracing the Journey

FIFTY YEARS OF THE OUTER SPACE TREATY Tracing the Journey FIFTY YEARS OF THE OUTER SPACE TREATY Tracing the Journey Editor Ajey Lele INSTITUTE FOR DEFENCE STUDIES & ANALYSES NEW DELHI PENTAGON PRESS Fifty Years of the Outer Space Treaty: Tracing the Journey Editor: Ajey Lele First Published in 2017 Copyright © Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi ISBN 978-81-8274-948-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without first obtaining written permission of the copyright owner. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, or the Government of India. Published by PENTAGON PRESS 206, Peacock Lane, Shahpur Jat New Delhi-110049 Phones: 011-64706243, 26491568 Telefax: 011-26490600 email: [email protected] website: www.pentagonpress.in In association with Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No. 1, Development Enclave, New Delhi-110010 Phone: +91-11-26717983 Website: www.idsa.in Printed at Avantika Printers Private Limited. Contents Foreword vii About the Contributors xi Introduction 1 SECTION I DEBATING OUTER SPACE TREATY 1. Evolution of the Outer Space Treaty 13 Ram S. Jakhu 2. Outer Space Treaty and International Relations Theory: For the Benefit of All Mankind 20 Joan Johson Freese 3. Outer Space Treaty: An Appraisal 24 G.S. Sachdeva 4. Relevance and Limitations of Outer Space Treaty in 21st Century 48 Ranjana Kaul 5.