More Explaining: Isaiah Berlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

American Expatriate Writers and the Process of Cosmopolitanism a Dissert

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Beyond the Nation: American Expatriate Writers and the Process of Cosmopolitanism A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Alexa Weik Committee in charge: Professor Michael Davidson, Chair Professor Frank Biess Professor Marcel Hénaff Professor Lisa Lowe Professor Don Wayne 2008 © Alexa Weik, 2008 All rights reserved The Dissertation of Alexa Weik is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2008 iii To my mother Barbara, for her everlasting love and support. iv “Life has suddenly changed. The confines of a community are no longer a single town, or even a single nation. The community has suddenly become the whole world, and world problems impinge upon the humblest of us.” – Pearl S. Buck v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………… iii Dedication………………………………………………………………….. iv Epigraph……………………………………………………………………. v Table of Contents…………………………………………………………… vi Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………. vii Vita………………………………………………………………………….. xi Abstract……………………………………………………………………… xii Introduction………………………………………………………………….. 1 Chapter 1: A Brief History of Cosmopolitanism…………...………………... 16 Chapter 2: Cosmopolitanism in Process……..……………… …………….... 33 -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

02 March 2003 CHART #1347 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums ALL THE THINGS SHE SAID WORK IT COME AWAY WITH ME BEAUTIFUL COLLISION 1 t.A.T.u 21 Missy Elliott 1 Norah Jones 21 Bic Runga Last week 2 / 6 weeks UNIVERSAL Last week 21 / 7 weeks WARNER Last week 1 / 47 weeks Platinum x6 / CAPITOL/EMI Last week 18 / 31 weeks Platinum x3 / SONY NU-FLOW THE GAME OF LOVE BRUSHFIRE FAIRYTALES THE LAST TEMPTATION 2 Big Brovaz 22 Santana feat. Michelle Branch 2 Jack Johnson 22 Ja Rule Last week 3 / 6 weeks Gold / SONY Last week 8 / 17 weeks BMG Last week 3 / 25 weeks Platinum x2 / CAPITOL/EMI Last week 27 / 7 weeks UNIVERSAL Lose Yourself DIRRTY THE RECORD A RUSH OF BLOOD TO THE HEAD 3 Eminem 23 Christina Aguilera 3 Bee Gees 23 Coldplay Last week 1 / 12 weeks Platinum / UNIVERSAL Last week 45 / 11 weeks BMG Last week 4 / 27 weeks Platinum x6 / UNIVERSAL Last week 16 / 22 weeks Platinum / CAPITOL/EMI BEAUTIFUL I'M GONNA GETCHA GOOD 8 MILE BETTER DAYZ 4 Christina Aguilera 24 Shania Twain 4 Soundtrack 24 2Pac Last week 18 / 5 weeks BMG Last week 14 / 14 weeks UNIVERSAL Last week 2 / 14 weeks Platinum x3 / UNIVERSAL Last week 21 / 6 weeks UNIVERSAL BORN TO TRY HEY MA The Eminem Show FEELS SO GOOD 5 Delta Goodrem 25 Cam'Ron 5 Eminem 25 Atomic Kitten Last week 34 / 3 weeks SONY Last week 17 / 7 weeks UNIVERSAL Last week 7 / 36 weeks Platinum x7 / UNIVERSAL Last week 39 / 15 weeks Platinum / VIRGIN/EMI BIG YELLOW TAXI WHO YOU WITH 100TH WINDOW A NEW DAY AT MIDNIGHT 6 Counting Crows Feat. -

Deep Learning

Chapter 12 Deep Learning 12.1 Introduction In his famous book, "The nature of Statistical Learning Theory:" [37], Vladimir Vapnik stated (in 1995) the four historical periods in the area of learning theory as: 1. Constructing first learning machine 2. Constructing fundamentals of the theory 3. Constructing the neural network 4. Constructing alternatives to the neural network The very existence of the fourth period was a failure of neural networks. Vapnik and others came up with various alternatives to neural network that were far more technologically feasible and efficient in solving the problems at hand at the time and neural networks slowly became history. However, with the modern technological advances, neural networks are back and we are in the fifth historical period: “Re- birth of neural network.” With re-birth, the neural networks are also renamed into deep neural networks or simply deep networks. The learning process is called as deep learning. However, deep learning is probably one of the most widely used and misused term. Since inception, there were no sufficient success stories to back up the over-hyped concept of neural networks. As a result they got pushed back in preference to more targeted ML technologies that showed instant success, e.g., evolutionary algorithms, dynamic programming, support vector machines, etc. The concept of neural networks or artificial neural networks (ANNs) was simple: to replicate the processing methodology of human brain which is composed of connected network of neurons. ANN was proposed as a generic solution to any type of learning problem, just like human brain is capable of learning to solve any problem. -

PDF Download Dangerously in Love Ebook

DANGEROUSLY IN LOVE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Alison Hobbs | 239 pages | 29 Oct 2009 | Strebor Books International, LLC | 9781593090487 | English | Mitchellville, United States Dangerously In Love PDF Book But when it comes to certain personal things any normal person wouldn't tell people they don't know, I just feel like I don't have to [talk about it]. The idea of individual releases emanated from the group's manager and Beyonce ' s father, Mathew. Entertainment Weekly. With different types of music for each member to produce, the albums were not intended to compete on the charts. Although the last two releases only reached the top five on the Hot , like "Baby Boy", it attained more immediate and commercial successes which propelled the album atop the chart and helped it earn multi-platinum certifications. Excluir playlist Cancelar Salvar. Big markets only. With high-energy songs like "Crazy in Love" and "Naughty Girl", however, the album's focal mode is slow and moody. Austin Chronicle. This review contains spoilers , click expand to view. Good article nominee. Not to insult your intelligence, but it doesn't; there isn't even a verb in Dangerously in Love. What on Earth is the difference? At any rate, I would suggest that Talk:Dangerously in Love would be a good place to discuss this, if only to prevent this same discussion from iterating many times in relation to the same article. Buyers who pre-ordered the album online received links where they could download a song called "I Can't Take No More. Knowles co-wrote and co-produced most of the tracks here, and although she's to be applauded for her musical adventurism, she deserves better material. -

Singer and Former Destiny's Child Member Kelly Rowland Discovers

One and only Rowland has recently started eating in restaurants by herself. (She’s a fan of Miami’s Cuban food scene.) “I’m very social, but I think it’s as important to spend time by yourself as it is to spend time with family and friends.” Ring, Di Modolo. Solid bangle, M+J Savitt; all others, Catherine Weitzman Singer and former Destiny’s Child member Kelly Rowland discovers the freedoms (and fears) of finally being out on her own. By Michele Shapiro Photographs by Riccardo Tinelli goingsolo 146 Water baby “I love to fish. My father introduced me to it when I was 4 or 5. I put worms on the hook. I didn’t mind. I was really a tomboy when I was younger,” Rowland says. bout five years ago, pop-music star Kelly Rowland made her first real estate investment, a five- bedroom home on the outskirts of Houston. She had no idea living alone would turn out to be such a drag. “The house was too big for me. It was a beau- Atiful home, and I got a good deal on it, but it was just me living there, and it was huge,” she says. At first, the idea of establishing her independence after 13 years as one third of the mega-trio Destiny’s Child seemed appealing. Not only did Rowland, Michelle Williams and Beyoncé Knowles perform together, but Rowland had been living with the Knowleses since she was 9 years old, having moved to Houston from Atlanta to eat, breathe and sleep Destiny’s Child. -

'Nakwaxda'xw First Nations by AFTAB

AN EXPERIMENT IN THERAPEUTIC PLANNING: Learning with the Gwa’sala-’Nakwaxda’xw First Nations by AFTAB ERFAN A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (PLANNING) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) September 2013 ©Aftab Erfan, 2013 Abstract Many of the communities in which planners work are characterized by deeply rooted conflict and collective trauma, a legacy of various forms of injustice, including some that have been enabled by the planning profession itself. In this context, can planning play a healing or therapeutic role, without recreating or perpetuating the cycles of oppression? This dissertation reflects on my community-based action research on Tsulquate, a small First Nations reserve on Vancouver Island, where the Gwa’sala and ‘Nakwaxda’xw people have lived since relocation in 1964. Between 2009 and 2012, and particularly over a year of intensive fieldwork, I engaged in this community to assist in the ambitious task of addressing intergenerational trauma, the importance of which was expressed within the Band’s newly created Comprehensive Community Plan. Written as mixed-genre creative analytic process (CAP) ethnography, the dissertation tells the stories of my engagement, and in particular of a series of public, intergenerational workshops I facilitated using a methodology called Deep Democracy. I document evidence of modest but promising patterns of individual and collective ‘healing’ and ‘transformation’ in the course of the workshops, and evaluate the effectiveness of my tools and approaches using first person (reflective), second person (interpersonal), and third person (informant-based) sources of information. -

Kelly Rowland

Kelly Rowland Being a part of the sensational girl group Destiny’s Child had this star rising to fame in the early 1990s. Kelly Rowland was born in Atlanta, Georgia, but, at the age of eight, she relocated to Houston, Texas, where she was placed in R&B group Destiny’s Child, which ultimately included Beyonce Knowles and Michelle Williams. After hours of practicing in Tina Knowles’s hair salon and their backyards, their hard work paid off when the girls signed a record deal with Columbia Records in 1997. With powerhouse voices and songs like “Bills, Bills, Bills” and “Say My Name,” it’s no surprise that they became one of the most successful girl groups of all time. In 2005, they officially called it quits, and the girls pursued their solo careers. Rowland’s debut album Simply Deep hit number 12 on the Billboard charts; she released her follow-up albumMs. Kelly in 2007 and embarked on a world tour. In addition to her singing success, the star expanded her talents to acting, appearing on both the small and big screens. She also appeared as a judge on the U.K. televised singing competition, The X Factor. Always having a humble heart, in 2005, Rowland teamed up with Beyonce after Hurricane Katrina to start The Survivor Foundation. Through their efforts, they were able to provide housing for victims and evacuees in Houston. In 2010, she launched another charitable entity, I Heart My Girlfriends, which focuses on a range of issues including self-esteem, date violence protection, abstinence, and community service. -

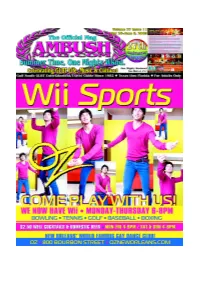

Gaymardigras.COM • Gayeasterparade.COM

GayMardiGras.COM • GayEasterParade.COM • GayNewOrleans.COM • May 26-June 8, 2009 • The Official Mag: AmbushMag.COM • 1 2 • The Official Mag: AmbushMag.COM • May 26-June 8, 2009 • Official Southern Decadence Guide • SouthernDecadence.COM GayMardiGras.COM • GayEasterParade.COM • GayNewOrleans.COM • May 26-June 8, 2009 • The Official Mag: AmbushMag.COM • 3 NIGHTS • Friday, June 5 –Sunday, June 7 on Friday, May 29. Enjoy the all-you-can- • 1am-8am: Magic Journeys is back and drink beer or soda bust from 9pm to 1am the "official" dish better than ever with DJ David Knapp on for only $5.00. Anyone wearing only a Friday night, DJ Tony Moran on Saturday towel gets a free shot at the back bar. If you night and DJs Peter Rauhofer and Offer forget your towel, the Lords will have them Nissim spinning Sunday night. available for $1.00 and you can check your by Rip & Marsha Naquin-Delain BEACH BALL LUAU (“Get lei’d and clothes for free. RipandMarsha.COM get wet!”) • Friday, June 5 • 8pm-1am: The For more information visit the Lords E-mail: [email protected] lush tropical nighttime setting at the Buena of Leather website at lordsofleather.com. Vista Palace Hotel sets the stage for the Renowned Circuit Promoter Johnny Chisholm Presents first ever “Beach Ball-Luau”! Grab your Stonewall Library & One Mighty Weekend June 4-7 in Orlando; Destiny's Child's coconuts and your hula skirt and get ready Archives Exhibit Explores Kelly Rowland Featured Star at One Mighty Party to shake it to the world’s hottest tracks with DJ Joe Gauthreaux. -

Find PDF Ms. Kelly

50EZSIISPZ89 » eBook < Ms. Kelly Ms. Kelly Filesize: 5.07 MB Reviews The very best book i actually read through. I have got read through and i am certain that i will likely to read through yet again yet again down the road. I realized this ebook from my dad and i suggested this book to learn. (Alfreda Barrows) DISCLAIMER | DMCA VBTGMALDWA5Y / Kindle ~ Ms. Kelly MS. KELLY Alphascript Publishing. Taschenbuch. Condition: Neu. Neuware - Ms. Kelly is the second solo studio album by American R&B singer Kelly Rowland. It was released by Columbia Records in collaboration with Music World Entertainment and Sony Music during the third quarter of 2007, beginning with most European territories on June 22. Rowland's first regular solo release in four years, the album was renamed and delayed numerous times pript to its official release. Originally branded My Story and expected for a mid-2006 release, the project was eventually moved to 2007 in favor of a 'multi- tiered marketing strategy' and additional recording sessions. Willed to produce a more personal eort aer fast-recorded 2002 album Simply Deep, Rowland contributed nine tracks to the re-worked version, Ms. Kelly, which took her solo work further into urban music markets, involving production by Scott Storch, Polow da Don, Soulshock & Karlin and singer Tank among others. The album scored medicore commercial success, debuting with the top ten on the Billboard 200 chart, but underperformed internationally, missing the top forty on most charts elsewhere. 116 pp. Englisch. Read Ms. Kelly Online Download PDF Ms. Kelly 0UZK1YBXMOI0 » eBook > Ms. Kelly Related PDFs Barabbas Goes Free: The Story of the Release of Barabbas Matthew 27:15-26, Mark 15:6-15, Luke 23:13-25, and John 18:20 for Children Paperback. -

About Kelly Rowland the Hit-Making Process Is Second Nature to Four-Time GRAMMY-Winning Singer / Songwriter / Actress, Kelly Ro

About Kelly Rowland The hit-making process is second nature to four-time GRAMMY-winning singer / songwriter / actress, Kelly Rowland. A global pop star since the age of 16, Kelly grew up in the spotlight as a member of Destiny’s Child, one of the best-selling groups of all time. Her powerful voice a key ingredient in the group’s awe-inspiring list of chart-toppers and dance floor smashes — including four No. 1 singles in the U.S. and more than 60 million albums sold worldwide — Kelly Rowland has blossomed into a stunning solo artist who has winningly collaborated with hip-hop heavyweights (Lil’ Wayne, Nelly), international producer-DJs (David Guetta, Alex Gaudino) and sought-after songwriters / producers (Rico Love, Ne-Yo, Salaam Remi, Rodney Jerkins) alike. As a solo artist, Rowland has released four successful studio albums – “Simply Deep,” “Ms. Kelly,” “Here I Am” and her most recent, “Talk A Good Game (June 2013)” – selling more than five million records. The talents which contributed to the monster success of Destiny’s Child and which were showcased on Kelly’s first forays as a soloist, such as the 2002 GRAMMY Award winning song “Dilemma (with Nelly),” have been further evidenced by her gold and platinum solo albums and hit songs including, “Like This (with Eve),” “Stole,” “Breathe Gentle (with Tiziano Ferro),” “When Love Takes Over (with David Guetta)” and “Motivation (with Lil’ Wayne),” which have topped music charts all over the world. Kelly’s beautiful voice and effervescent personality have not only garnered her critical and commercial success in the music arena, but her movie star good looks, unique style and limitless drive have also generated numerous opportunities in television, film and fashion. -

University Microfilms. a XEROX Company , Ann Arbor, Michigan

71-18,042 LEE, Paul Gregory, 1942- SUBJECTS AND AGENTS. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1970 Language and Literature, linguistics University Microfilms. AXEROX Company , Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED SUBJECTS AND AGENTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Paul Gregory Lee, A.B., M.A. *«*«*« The Ohio State University 1970 Approved by /jljA j) • iJhd&U Adviser Department of Linguistics ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am very grateful to the people who have criticized the drafts of this dissertation, expecially my adviser, Charles Fillmore. Others who have helped me a great deal are Gaberell Drachman, David Stampe, and Arnold Zvicky. ii VITA March 2,19**2 . .''i . Born - Hamilton, Ohio 1 9 6 5 ............. A.B., Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1965-1967......... Teaching Assistant, Department of Linguistics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1967 ............. M.A., The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1967-1969 ......... Research Associate, Department of Linguistics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1969-1970 ......... Administrative Associate, Department of Linguistics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio PUBLICATIONS "The English Preposition WITH." Working Papers in Linguistics No. 1, pp. 30-79, December 1967- "English Word-Stress." Papers from the Fifth Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, pp. 389-Vo6 , April 1969. "Do from Occur. Working Papers in Linguistics No. 3, pu. 1-21, June 1969. "Subjects and Agents." Working Papers in Linguistics No. 3, pp. 36- 113, June 1969. "The Deep Structure of Indirect Discourse." Working Papers in Linguistics No.