The Causes of Disappearance of Sword Lily Gladiolus Imbricatus L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Iris Sibirica) Im Westlichen Bodenseegebiet 27-51 ©Staatl

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Carolinea - Beiträge zur naturkundlichen Forschung in Südwestdeutschland Jahr/Year: 2011 Band/Volume: 69 Autor(en)/Author(s): Peintinger Markus Artikel/Article: Verbreitung, Populationsdynamik und Vergesellschaftung der Sibirischen Schwertlilie (Iris sibirica) im westlichen Bodenseegebiet 27-51 ©Staatl. Mus. f. Naturkde Karlsruhe & Naturwiss. Ver. Karlsruhe e.V.; download unter www.zobodat.at carolinea, 69 (2011): 27-51, 4 Abb.; Karlsruhe, 15.12.2011 27 Verbreitung, Populationsdynamik und Vergesellschaftung der Sibirischen Schwertlilie (Iris sibirica) im westlichen Bodenseegebiet MARKUS PEINTINGER Kurzfassung alle Streuwiesen mit Iris sibirica befinden sich in Natur- Die Sibirische Schwertlilie (Iris sibirica) ist eine ty- schutzgebieten und werden aus Naturschutzgründen pische Art der Streuwiesen (Molinion caeruleae) am einmal im Jahr gemäht. Bodenseeufer. Der beobachtete Rückgang einiger Po- pulationen wurde zum Anlass genommen, um Verände- Abstract rungen in der Populationsgröße und der Artenzusam- Distribution, population dynamics and phytoso- mensetzung von Iris sibirica-Wiesen zu untersuchen. ciology of Iris sibirica in the western part of Lake Es wurde hauptsächlich drei Fragen nachgegangen: Constance 1. Wie ist die aktuelle Verbreitung von Iris sibirica und Iris sibirica is a characteristic species for calcareous hat sich der Bestand in den letzten hundert Jahren ver- fen meadows (Molinion caeruleae) at the shore of Lake ändert? 2. Gibt es einen langfristigen Populationstrend Constance. Since a decline of local populations was 1992-2008? 3. Hat sich die Artenzusammensetzung observed, a more detailed study was initiated to exa- der Streuwiesen mit Iris sibirica-Wiesen zwischen den mine changes in population size and species compo- zwei untersuchten Zeitperioden 1988-1993 und 2003- sition of Iris sibirica meadows. -

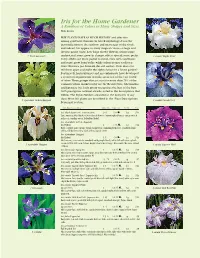

Iris for the Home Gardener a Rainbow of Colors in Many Shapes and Sizes Bob Lyons

Iris for the Home Gardener A Rainbow of Colors in Many Shapes and Sizes Bob Lyons FEW PLANTS HAVE AS MUCH HISTORY and affection among gardeners than iris. In Greek mythology, Iris is the personification of the rainbow and messenger of the Gods, and indeed, Iris appear in many magical colors—a large and diverse genus. Some have large showy flowers, others more I. ‘Black Gamecock’ understated; some grow in clumps, others spread; some prefer I. ensata ‘Angelic Choir’ it dry, others are more partial to moist, even wet conditions; and some grow from bulbs, while others return each year from rhizomes just beneath the soil surface. How does one tell them apart and make the right choice for a home garden? Fortunately, horticulturists and iris enthusiasts have developed a system of organization to make sense out of the vast world of irises. Three groups that account for more than 75% of the commercial iris market today are the Bearded Iris, Siberian Iris, and Japanese Iris. Each group recognizes the best of the best with prestigious national awards, noted in the descriptions that follow. The Dykes Medal is awarded to the finest iris of any class. More iris plants are described in the “Plant Descriptions: I. ×pseudata ‘Aichi no Kagayaki’ I. ensata ‘Cascade Crest’ Perennial” section. Latin Name Common Name Mature Size Light Soil Pot Size Price Iris ‘Black Gamecock’ Louisiana Iris 2–3 .8 d 1 g $14 Late; stunning blue black, velvet-colored flowers; hummingbird haven; can grow in 4 inches of standing water; DeBaillon Medal. Iris ×pseudata ‘Aichi no Kagayaki’ Iris Hybrid 2 . -

Hortus Botanicus Kaunensis Universitati Vytauti Magni

HORTUS BOTANICUS KAUNENSIS UNIVERSITATI VYTAUTI MAGNI 2016 HORTUS BOTANICUS KAUNENSIS UNIVERSITATI VYTAUTI MAGNI KAUNAS BOTANICAL GARDEN OF VYTAUTAS MAGNUS UNIVERSITY HORTUS BOTANICUS KAUNENSIS UNIVERSITATI VYTAUTI MAGNI Ž. E. Žilibero str. 6 Phone: +370 37 390033 LT–46324 Kaunas, Fax: +370 37 390133 Lithuania E-mail: [email protected] http://botanika.vdu.lt Compiled by Kristina Stankevičienė, Arūnas Balsevičius, Ričardas Narijauskas Director: dr Nerijus Jurkonis HISTORY OF THE BOTANICAL GARDEN Kaunas Botanical Garden was established in 1923 at Lithuanian University (later it was renamed after Vytautas Magnus) as the centre of botanical sciences. Former manor of famous nobleman Juozapas Godlevskis in Aukštoji Freda near Kaunas was chosen as a place for the Garden. Creation of the manor started at the end of the 17th century. The surrounding park was landscaped to adjust the ponds to the form of J and G letters. With only slight changes they have still remained. Presently, Kaunas Botanical Garden of VMU occupies the area of 62.5 hectares. Approximately 10864 different plants comprise the collections and expositions. HORTUS BOTANICUS KAUNENSIS UNIVERSITATI VYTAUTI MAGNI SECTORS OF PLANT COLLECTIONS AND DISPLAYS Sector of Medicinal, Aromatic Plants and Spices At the present time there are 786 cultivated examples of medicinal plants, aromatic plants and spices and 49 examples of Humulus lupulus. Collections are planted according to bioactive plant compounds classification. 26 species belong to the category of protected and rare plants. Sector of Dendrology There are 1367 cultivated examples in this sector. In 2011 extraordinary B. Galdikas oak grove was planted. It is comprised of 50 genetic clones of 31 famous Lithuanian oaks – nature monuments. -

Iris Sibirica and Others Iris Albicans Known As Cemetery

Iris Sibirica and others Iris Albicans Known as Cemetery Iris as is planted on Muslim cemeteries. Two different species use this name; the commoner is just a white form of Iris germanica, widespread in the Mediterranean. This is widely available in the horticultural trade under the name of albicans, but it is not true to name. True Iris albicans which we are offering here occurs only in Arabia and Yemen. It is some 60cm tall, with greyish leaves and one to three, strongly and sweetly scented, 9cm flowers. The petals are pure, bone- white. The bracts are pale green. (The commoner interloper is found across the Mediterranean basin and is not entitled to the name, which continues in use however. The wrongly named albicans, has brown, papery bracts, and off-white flowers). Our stock was first found near Sana’a, Yemen and is thriving here, outside, in a sunny, raised bed. Iris Sibirica and others Iris chrysographes Black Form Clumps of narrow, iris-like foliage. Tall sprays of darkest violet to almost black velvety flowers, Jun-Sept. Ht 40cm. Moist, well drained soil. Part shade. Deepest Purple which is virtually indistinguishable from black. Moist soil. Ht. 50cm Iris chrysographes Dykes (William Rickatson Dykes, 1911, China); Section Limniris, Series Sibericae; 14-18" (35-45 cm), B7D; Flowers dark reddish violet with gold streaks in the signal area giving it its name (golden writing); Collected by E. H. Wilson in 1908, in China; The Gardeners' Chronicle 49: 362. 1911. The Curtis's Botanical Magazine. tab. 8433 in 1912, gives the following information along with the color illustration. -

– Catalogue 2018 –

– CATALOGUE 2018 – Paeonia 'Cora Louise' Geranium 'Max Frei' 2018 PERENNIAL BARE ROOT CATALOGUE Dear Darwin Plants Customer, We proudly present to you our Perennial Bare Root Catalogue for 2018. As you probably noticed, the layout and colours have changed extensively. This Summer of 2017, Darwin Plants will move location to a brand new facillity in Rijsenhout, The Netherlands. This move will help us to serve you even better in the future. Being part of the ‘Kébol‘ organisation will not change anything in how we at Darwin Plants work with you. We are convinced it creates more opportunities for you as a customer in doing business with us! Fred Meiland As we do every year, we have added many new varieties to the range so that you the customer have the best selection of varieties from which to choose. Our goal is to provide you with outstanding quality bare root, so that you are able to succesfully grow and sell these plants. With our experienced staff, our goal is to help you achieve this. We are proud to offer you: Kees van der Meij Mark van Duyn • A wealth of skill and an experienced staff on hand to guide you from variety selection to cultural support. For information please contact: [email protected] • A dedicated customer service team that can help you with all your order and shipping enquiries. For information please contact: [email protected] • A knowlegable Perennial sales team, here to advise you which varieties to grow and how to grow them successfully. For information in the USA and Canada, please contact: [email protected] or [email protected]. -

SIBERIAN IRISES Don Witton

SIBERIAN IRISES Don Witton hen we had a vote, on our 20th Anniversary, to find the South Pennine Group’s favourite perennial, the iris came out top. I’m not surprised, as there are a wealth of different forms Wand I’ve been told that it is possible to have an iris in flower every month of the year. They have very beautiful flowers. They consist of upright petals in the centre of the flower, which are often called standards. These are surrounded on the outside by three large, colourful sepals that grow outwards or down, called falls. The base of the fall, which may be a different colour or have attractive veining, is known as the signal. I’m not an expert on all forms of iris; I struggle to grow the bulbous winter-flowering reticulata varieties, and I have never grown the large, summer-flowering, bearded iris as I’m told they need space for the sun to bake the surface-growing rhizomes. I don’t do space in my garden! But the type of iris I like best, and can grow well, is the Siberian iris, and there are plenty to choose from. Iris sibirica, which comes from Europe and west Asia, likes a moisture-retentive soil, grows up to one metre tall, and has long, tapering, grass-like foliage, never broader than one centimetre. It has thinner rhizomes than the bearded iris and they grow downwards into the ground, giving plants a standard ‘clumping perennial’ look. Although my garden dries out in the summer, these iris perform well for me in sun or part-shade, and I have acquired some excellent plants over the years. -

(2073) Proposal to Conserve the Name Pseudiris Chukr & A. Gil

Crespo & Alonso • (2073) Conserve Pseudiris or Limniris TAXON 61 (3) • June 2012: 684–685 enthusiasm for resurrecting an epithet that has not been used for over If this conservation proposal is not accepted, we will be left 200 years. The third option would reverse what has become estab- with only option 1, unless a further proposal is made to conserve or lished usage during the last 28 years, and would be destabilising. The to reject one or more names. second option is disagreeable, as it means conserving a name that was resurrected by Laundon for purely nomenclatural reasons, but which Acknowledgment would not have been taken up if the matter had been investigated more Thanks, as usual, to John McNeill for helpful improvements to thoroughly, but I feel that I have little choice but to take that route. the manuscript. (2073) Proposal to conserve the name Pseudiris Chukr & A. Gil against Pseudo-iris Medik. (Iridaceae), or to conserve Limniris against Pseudo-iris Manuel B. Crespo & Mª Ángeles Alonso CIBIO, Instituto de la Biodiversidad, Universidad de Alicante, P.O. Box 99, 03080 Alicante, Spain Author for correspondence: Manuel B. Crespo, [email protected] (2073) Pseudiris Chukr & A. Gil in Proc. Calif. Acad. Sci. 59: 725. However, as a validly published name under the Vienna Code 30 Dec 2008 [Monocot.: Irid.], nom. cons. prop. (McNeill & al. in Regnum Veg. 146. 2006), Pseudo-iris must be Typus: P. speciosa Chukr & A. Gil taken into account when it competes with names of lesser priority. If (H) Pseudo-iris Medik. in Hist. & Commentat. Acad. Elect. -

Botanická Zahrada IRIS.Indd

B-Ardent! Erasmus+ Project CZ PL LT D BOTANICAL GARDENS AS A PART OF EUROPEAN CULTURAL HERITAGE IRIS (KOSATEC, IRYS, VILKDALGIS, SCHWERTLILIE) Methodology 2020 Caspers Zuzana, Dymny Tomasz, Galinskaite Lina, Kurczakowski Miłosz, Kącki Zygmunt, Štukėnienė Gitana Institute of Botany CAS, Czech Republic University.of.Wrocław,.Poland Vilnius University, Lithuania Park.der.Gärten,.Germany B-Ardent! Botanical Gardens as Part of European Cultural Heritage Project number 2018-1-CZ01-KA202-048171 We.thank.the.European.Union.for.supporting.this.project. B-Ardent! Erasmus+ Project CZ PL LT D The. European. Commission. support. for. the. production. of. this. publication. does. not. con- stitute.an.endorsement.of.the.contents.which.solely.refl.ect.the.views.of.the.authors..The. European.Commission.cannot.be.held.responsible.for.any.use.which.may.be.made.of.the. information.contained.therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION OF THE GENUS IRIS .................................................................... 7 Botanical Description ............................................................................................... 7 Origin and Extension of the Genus Iris .................................................................... 9 Taxonomy................................................................................................................. 11 History and Traditions of Growing Irises ................................................................ 11 Morphology, Biology and Horticultural Characteristics of Irises ...................... -

Winter2019 Winter 2019 BCIS Bulletin

A RED DOT here means your membership renewal is NOW DUE. BB u u l l l l e e t t i i n n Vol. 14, No. 1, Winter 2019 Content, Editing: Richard Hebda Editing, Production: Joyce Prothero Dispatch: Richard Hebda 20182018 MORGANMORGAN--WOODWOOD AWARDAWARD (SIB) ‘Miss Apple’ (Marty Schafer Jan Sacks, 2009)Sacks, Jan Schafer (Marty Apple’ ‘Miss (SIB) bloom. Midseason 30“, Height 1. S0250 No. Seedling Baker. Ted by Photo Miss Apple, the 2018 Morgan-Wood Award Winner Miss Apple was a milestone in the breeding program of Marty Schafer and Jan Sacks in that it was their first red Siberian. True, not a fire engine red but a good red that grew and bloomed well. A worthy recipient of the Morgan-Wood Medal. BCIS Bulletin Winter 2019 1 President’s Message Winter 2019: SSuuppeerr SSiibbeerriiaannss aanndd mm uuchch mmoorree Richard J. Hebda, BC Iris Society President Welcome to the 2019 BC Iris Society (BCIS) annual Bulletin in which you will find wonderfully illustrated articles on a range of topics especially Siberian irises, Miss Apple a delightful showy Siberian being featured on the front cover. In addition to the bulletin we have been sending you by e- mail lots of information from many national and regional societies. We hope you are Ianson Bob by Photo enjoying these links. We encourage you to use the bulletin to share and exchange information about irises widely with friends, fellow gardeners and societies. Our bulletin contains several informative articles in addition to the announcements Richard J. Hebda, BCIS President and reports. -

Low Genetic Variation in Subpopulations of an Endangered Clonal Plant Iris Sibirica in Southern Poland

Ann. Bot. Fennici 45: 186–194 ISSN 0003-3847 (print) ISSN 1797-2442 (online) Helsinki 27 June 2008 © Finnish Zoological and Botanical Publishing Board 2008 Low genetic variation in subpopulations of an endangered clonal plant Iris sibirica in southern Poland Kinga Kostrakiewicz1,* & Ada Wróblewska2 1) Department of Plant Ecology, Institute of Botany, Jagiellonian University, Lubicz 46, PL-31-512 Kraków, Poland (corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected]) 2) Institute of Biology, University of Białystok, Świerkowa 20B, PL-15-950 Białystok, Poland Received 2 May 2007, revised version received 5 June 2007, accepted 31 July 2007 Kostrakiewicz, K. & Wróblewska, A. 2008: Low genetic variation in subpopulations of an endan- gered clonal plant Iris sibirica in southern Poland. — Ann. Bot. Fennici 45: 186–194. The spatial genetic structure in three subpopulations of the endangered clonal plant Iris sibirica from southern Poland was investigated. The subpopulations occurred in differ- ent habitats, i.e. in a Molinietum caeruleae community, a Phragmites australis patch and in a willow brushwood. Using 13 enzymatic systems, sixteen loci were evaluated. The very low genetic diversity (P = 0%–18.7%, A = 1.0%–1.19%, HO = 0.000–0.009) observed within the subpopulations is probably due to lack of recruitment, habitat fragmentation and/or historical causes. Five distinct multilocus genotypes, detected from 148 collected samples in the subpopulations, supported this observation. This fact illustrated that only clonal growth could maintain the present low genetic variation through the domination of a single or a few clones within these sites. Moderate genetic differentiation (FST = 0.077, P < 0.001) that varies strongly between pairs of subpopu- lations, was observed, thereby suggesting substantial gene flow between populations. -

Iris Tibetica, a New Combination in I. Ser. Lacteae (Iridaceae) from China: Evidence from Morphological and Chloroplast DNA Analyses

Phytotaxa 338 (3): 223–240 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2018 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.338.3.1 Iris tibetica, a new combination in I. ser. Lacteae (Iridaceae) from China: evidence from morphological and chloroplast DNA analyses EUGENY V. BOLTENKOV1,2*, ELENA V. ARTYUKOVA3, MARINA M. KOZYRENKO3 & ANNA TRIAS- BLASI4 1Botanical Garden-Institute, Far Eastern Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, ul. Makovskogo 142, 690024 Vladivostok, Russian Federation; e-mail: [email protected] 2Komarov Botanical Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, ul. Prof. Popova 2, 197376 St. Petersburg, Russian Federation 3Federal Scientific Center of the East Asia Terrestrial Biodiversity, Far Eastern Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, prospect 100- letiya Vladivostoka 159, 690022 Vladivostok, Russian Federation 4Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond TW9 3AE, U.K. *author for correspondence Abstract Historically, the species composition of Iris ser. Lacteae has been controversial. Morphological and molecular analyses have been conducted here including specimens covering most of their distribution range. The results suggest I. ser. Lacteae includes three species: the well-known I. lactea and I. oxypetala, plus a newly defined taxon which is endemic to the Gansu and Qinghai provinces, China. We here propose it as a new combination at the species rank, I. tibetica. Morphologically, this species is close to I. lactea but differs by its horizontal, creeping rhizome, scapes with no more than two flowers, its bracts reach the middle of the first flower, its broader inner perianth segments, its obovate with obtuse apex outer perianth segments, and its fruit apex always abruptly narrowed to a very short beak. -

Ebruozdenız.Pdf

ANKARA ÜNİVERSİTESİ FEN BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ ANKARA ÜNİVERSİTESİ FEN FAKÜLTESİ HERBARYUMU’NDAKİ (ANK) IRIDACEAE FAMİLYASININ REVİZYONU VE VERİTABANININ HAZIRLANMASI Ebru ÖZDENİZ BİYOLOJİ ANABİLİM DALI ANKARA 2009 Her Hakkı Saklıdır ÖZET Yüksek Lisans Tezi ANKARA ÜNİVERSİTESİ FEN FAKÜLTESİ HERBARYUMU’NDAKİ (ANK) IRIDACEAE FAMİLYASININ REVİZYONU VE VERİTABANININ HAZIRLANMASI Ebru ÖZDENİZ Ankara Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Biyoloji Anabilim Dalı Danışman: Prof. Dr. Latif KURT ANK Herbaryumun’da bulunan Iridaceae familyasına ait 390 bitki örneğinin incelenmesi sonucu 5 cins ve bu cinslere ait toplam 78 takson tespit edilmiştir. Toplam tür sayısı 54’tür. 27 tür Türkiye için endemiktir. Iridaceae familyasının ANK Herbaryumu’ndaki türlere göre takson sayısı şöyledir: Iris (33), Crocus (32), Gladiolus (7), Gynandriris (1) ve Romulea (5)’ dir. ANK Herbaryumu’ndaki Iridaceae familyası üyelerinin fitocoğrafik bölgelere dağılım yüzdeleri ise; İran-Turan % 30, Doğu Akdeniz % 24, Avrupa-Sibirya % 10, Öksin % 5 ve Akdeniz % 3’ tür. Temmuz 2009, 250 sayfa Anahtar Kelimeler: Revizyon, Iridaceae, ANK, Veritabanı, Herbaryum. i ABSTRACT Master Thesis THE REVISION OF IRIDACAE FAMILY AT HERBARIUM OF THE FACULTY OF SCIENCE (ANK) AND PREPERATION OF THE DATABASE Ebru ÖZDENİZ Ankara University Institue of Science and Technology Department of Biology Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Latif KURT Iridaceae family was revised at ANK Herbarium and found out that 390 plant specimens belonging to 5 genera and 78 taxa were deposited. Total species are 54. 27 species are endemic for Turkey. According to species in ANK Herbarium the number of taxa of Iridaceae family: Iris (33), Crocus (32), Gladiolus (7), Romulea (5) and Gynandriris (1). Phytogeographic areas are follows: Irano-Turanien % 30, East Mediterraenean % 24, Euro-Siberian % 10, Euxine % 5 and Mediterraenean % 3.