Neratinib Efficacy and Circulating Tumor DNA Detection of HER2 Mutations in HER2 Nonamplified Metastatic Breast Cancer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circulating Tumor DNA As Biomarkers for Cancer Detection

Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 15 (2017) 59–72 HOSTED BY Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics www.elsevier.com/locate/gpb www.sciencedirect.com REVIEW Circulating Tumor DNA as Biomarkers for Cancer Detection Xiao Han 1,2,a, Junyun Wang 1,b, Yingli Sun 1,*,c 1 CAS Key Laboratory of Genomic and Precision Medicine, China Gastrointestinal Cancer Research Center, Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China Received 1 July 2016; revised 13 December 2016; accepted 20 December 2016 Available online 7 April 2017 Handled by Cesar Wong KEYWORDS Abstract Detection of circulating tumor DNAs (ctDNAs) in cancer patients is an important com- Precision medicine; ponent of cancer precision medicine ctDNAs. Compared to the traditional physical and biochemical Liquid biopsy; methods, blood-based ctDNA detection offers a non-invasive and easily accessible way for cancer Circulating tumor DNA; diagnosis, prognostic determination, and guidance for treatment. While studies on this topic are Biomarker; currently underway, clinical translation of ctDNA detection in various types of cancers has been Clinical diagnosis; attracting much attention, due to the great potential of ctDNA as blood-based biomarkers for early Cell-free nucleic acids diagnosis and treatment of cancers. ctDNAs are detected and tracked primarily based on tumor- related genetic and epigenetic alterations. In this article, we reviewed the available studies on ctDNA detection and described the representative methods. We also discussed the current understanding of ctDNAs in cancer patients and their availability as potential biomarkers for clin- ical purposes. Considering the progress made and challenges involved in accurate detection of speci- fic cell-free nucleic acids, ctDNAs hold promise to serve as biomarkers for cancer patients, and further validation is needed prior to their broad clinical use. -

797 Circulating Tumor DNA and Circulating Tumor Cells for Cancer

Medical Policy Circulating Tumor DNA and Circulating Tumor Cells for Cancer Management (Liquid Biopsy) Table of Contents • Policy: Commercial • Coding Information • Information Pertaining to All Policies • Policy: Medicare • Description • References • Authorization Information • Policy History • Endnotes Policy Number: 797 BCBSA Reference Number: 2.04.141 Related Policies Biomarkers for the Diagnosis and Cancer Risk Assessment of Prostate Cancer, #336 Policy1 Commercial Members: Managed Care (HMO and POS), PPO, and Indemnity Plasma-based comprehensive somatic genomic profiling testing (CGP) using Guardant360® for patients with Stage IIIB/IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY when the following criteria have been met: Diagnosis: • When tissue-based CGP is infeasible (i.e., quantity not sufficient for tissue-based CGP or invasive biopsy is medically contraindicated), AND • When prior results for ALL of the following tests are not available: o EGFR single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertions and deletions (indels) o ALK and ROS1 rearrangements o PDL1 expression. Progression: • Patients progressing on or after chemotherapy or immunotherapy who have never been tested for EGFR SNVs and indels, and ALK and ROS1 rearrangements, and for whom tissue-based CGP is infeasible (i.e., quantity not sufficient for tissue-based CGP), OR • For patients progressing on EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). If no genetic alteration is detected by Guardant360®, or if circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is insufficient/not detected, tissue-based genotyping should be considered. Other plasma-based CGP tests are considered INVESTIGATIONAL. CGP and the use of circulating tumor DNA is considered INVESTIGATIONAL for all other indications. 1 The use of circulating tumor cells is considered INVESTIGATIONAL for all indications. -

The Interplay of Circulating Tumor DNA and Chromatin Modification

Zhang et al. Molecular Cancer (2019) 18:36 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-019-0989-z REVIEW Open Access The interplay of circulating tumor DNA and chromatin modification, therapeutic resistance, and metastasis Lei Zhang1,2,3†, Yiyi Liang1,2,3†, Shifu Li1,2,3†, Fanyuan Zeng1,2,3†, Yongan Meng1,2,3†, Ziwei Chen1,2,3, Shuang Liu3, Yongguang Tao1,2,3,4* and Fenglei Yu4* Abstract Peripheral circulating free DNA (cfDNA) is DNA that is detected in plasma or serum fluid with a cell-free status. For cancer patients, cfDNA not only originates from apoptotic cells but also from necrotic tumor cells and disseminated tumor cells that have escaped into the blood during epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Additionally, cfDNA derived from tumors, also known as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), carries tumor-associated genetic and epigenetic changes in cancer patients, which makes ctDNA a potential biomarker for the early diagnosis of tumors, monitory and therapeutic evaluations, and prognostic assessments, among others, for various kinds of cancer. Moreover, analyses of cfDNA chromatin modifications can reflect the heterogeneity of tumors and have potential for predicting tumor drug resistance. Keywords: ctDNA, Chromatin modification, Therapeutic resistance, Metastasis, Tumor heterogeneity Biological features of ctDNA enter the blood in single, double or triple forms, and Peripheral circulating free DNA is DNA that is detected thus most ctDNA shows significant fragmentary charac- in plasma or serum fluid with a cell-free status. It may teristics. Moreover, the half-life of ctDNA in the blood originate from apoptosis or necrosis. The amount of cir- circulation is less than 2 hours [3]. -

Circulating Cell-Free DNA in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Current Insights and Outlook

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by edoc REVIEW published: 26 March 2018 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00078 Circulating Cell-Free DNA in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Current Insights and Outlook Charlotte K. Y. Ng1,2*, Giovan Giuseppe Di Costanzo3, Luigi M. Terracciano1 and Salvatore Piscuoglio1* 1 Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland, 2 Department of Biomedicine, Hepatology Laboratory, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland, 3 Department of Transplantation – Liver Unit, Cardarelli Hospital, Naples, Italy Over the past decade, the advancements in massively parallel sequencing have pro- vided a new paradigm in biomedical research to uncover the genetic basis of human diseases. Integration of ‘omics information has begun transforming clinical management of cancer patients in terms of diagnostics and treatment options, giving rise to the era of precision medicine. Currently, nucleic acids for molecular profiling for patients diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are typically obtained from resected tumor mate- rials or transplanted neoplastic liver and occasionally from biopsies. Given the intrinsic risks associated with such invasive procedures, circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) has been proposed as an alternative source for tumor DNA. Circulating cfDNA is a type of Edited by: cell-free nucleic acid that derives from apoptotic, necrotic, as well as living eukaryotic Venancio Avancini Alves, University of São Paulo, Brazil cells. Importantly, the detection of abnormal forms of circulating cfDNA that originate Reviewed by: from cancer cells provides a new tool for cancer detection, disease monitoring, and Fernando Schmitt, molecular profiling. Currently, cfDNA is beginning to be adopted into clinical practice Universidade do Porto, Portugal Marco Volante, as a non-invasive tool to monitor disease by tracking the evolution of disease-specific Università degli Studi di Torino, Italy genetic alterations in several major cancer types. -

Highly Sensitive Detection of Sentinel Lymph Node Metastasis of Breast Cancer by Digital PCR for RASSF1A Methylation

2382 ONCOLOGY REPORTS 42: 2382-2389, 2019 Highly sensitive detection of sentinel lymph node metastasis of breast cancer by digital PCR for RASSF1A methylation MIZUHO ABE, NAOFUMI KAGARA, TOMOHIRO MIYAKE, TOMONORI TANEI, YASUTO NAOI, MASAFUMI SHIMODA, KENZO SHIMAZU, SEUNG JIN KIM and SHINZABURO NOGUCHI Department of Breast and Endocrine Surgery, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita, Osaka 565‑0871, Japan Received June 4, 2019; Accepted September 19, 2019 DOI: 10.3892/or.2019.7363 Abstract. One-step nucleic acid amplification (OSNA) and is confirmed by postoperative pathological examination of targeting cytokeratin 19 (CK19) mRNA expression and permanent sections (3,4). One‑step nucleic acid amplification pathological examination are widely used for the intraop- (OSNA) can be used to detect SN metastasis through the erative diagnosis of sentinel node (SN) metastasis. The aim amplification of cytokeratin 19 (CK19) mRNA (which is of the present study was to develop a novel assay for detecting expressed in tumor cells, but not normal cells of LNs) with the SN metastasis by targeting Ras association domain-containing same accuracy as routine pathological examination (5). OSNA protein 1 (RASSF1A) methylation in tumor cells, and to is also used to determine total tumor load (TTL) in SNs as the compare its performance with OSNA. Using digital PCR with sum of CK19 mRNA copies, which is reportedly useful for methylation-specific restriction enzymes (RE-dMSP), our predicting non-SN metastatic status (6,7), as well as patient assay was able to detect ≥3 copies of methylated DNA per prognosis (8). well, and was ≥10 times more sensitive than real‑time PCR However, TTL determination by OSNA does not always with bisulfite modification. -

Circulating Tumor DNA Testing Opens New Perspectives in Melanoma Management

cancers Review Circulating Tumor DNA Testing Opens New Perspectives in Melanoma Management 1, 1, 1 1 Alessandra Sacco y , Laura Forgione y, Marianeve Carotenuto , Antonella De Luca , Paolo A. Ascierto 2 , Gerardo Botti 3 and Nicola Normanno 1,* 1 Cell Biology and Biotherapy Unit, Istituto Nazionale Tumori-IRCCS-Fondazione G. Pascale, 80131 Naples, Italy; [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (L.F.); [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (A.D.L.) 2 Department of Melanoma, Cancer Immunotherapy and Development Therapeutics, Istituto Nazionale Tumori IRCCS Fondazione Pascale, 80131 Napoli, Italy; [email protected] 3 Scientific Direction, Istituto Nazionale Tumori IRCCS Fondazione Pascale, 80131 Napoli, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-081-5903-826 These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 15 September 2020; Accepted: 8 October 2020; Published: 10 October 2020 Simple Summary: Melanoma, like other solid tumors, releases DNA molecules that are referred to as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), into the blood and other biological fluids. ctDNA analysis performed with molecular biology techniques can provide important information on the aggressiveness of the disease and its genetic characteristics. This review aims to highlight all the possible clinical applications of ctDNA analysis that can contribute to an improvement in the diagnosis and therapy of melanoma. Abstract: Malignant melanoma accounts for about 1% of all skin cancers, but it causes most of the skin cancer-related deaths. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) testing is emerging as a relevant tool for the diagnosis and monitoring of cancer. -

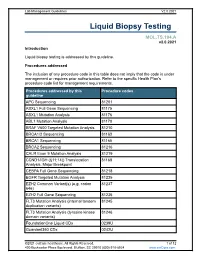

Liquid Biopsy Testing

Lab Management Guidelines V2.0.2021 Liquid Biopsy Testing MOL.TS.194.A v2.0.2021 Introduction Liquid biopsy testing is addressed by this guideline. Procedures addressed The inclusion of any procedure code in this table does not imply that the code is under management or requires prior authorization. Refer to the specific Health Plan's procedure code list for management requirements. Procedures addressed by this Procedure codes guideline APC Sequencing 81201 ASXL1 Full Gene Sequencing 81175 ASXL1 Mutation Analysis 81176 ABL1 Mutation Analysis 81170 BRAF V600 Targeted Mutation Analysis 81210 BRCA1/2 Sequencing 81163 BRCA1 Sequencing 81165 BRCA2 Sequencing 81216 CALR Exon 9 Mutation Analysis 81219 CCND1/IGH (t(11;14)) Translocation 81168 Analysis, Major Breakpoint CEBPA Full Gene Sequencing 81218 EGFR Targeted Mutation Analysis 81235 EZH2 Common Variant(s) (e.g. codon 81237 646) EZH2 Full Gene Sequencing 81236 FLT3 Mutation Analysis (internal tandem 81245 duplication variants) FLT3 Mutation Analysis (tyrosine kinase 81246 domain variants) FoundationOne Liquid CDx 0239U Guardant360 CDx 0242U ©2021 eviCore healthcare. All Rights Reserved. 1 of 12 400 Buckwalter Place Boulevard, Bluffton, SC 29910 (800) 918-8924 www.eviCore.com Lab Management Guidelines V2.0.2021 Procedures addressed by this Procedure codes guideline Hematolymphoid Neoplasm Molecular 81450 Profiling; 5-50 genes IDH1 Mutation Analysis 81120 IDH2 Mutation Analysis 81121 IGH@/BCL2 (t(14;18)) Translocation 81278 Analysis, Major Breakpoint Region (MBR) and Minor Cluster Region (mcr) Breakpoints JAK2 Targeted Mutation Analysis (e.g 81279 exons 12 and 13) JAK2 V617F Targeted Mutation Analysis 81270 KIT Targeted Sequence Analysis 81272 KIT D816 Targeted Mutation Analysis 81273 KRAS Exon 2 Targeted Mutation Analysis 81275 KRAS Targeted Mutation Analysis, 81276 Additional Variants MGMT Promoter Methylation Analysis 81287 MLH1 Sequencing 81292 Molecular Tumor Marker Test 81400 81401 81402 g 81403 n i 81405 t 81406 s e T 81407 81408 y s 81479 p o Molecular Tumor Marker Test 88271 i B MPL Common Variants (e.g. -

Circulating Tumor DNA As an Emerging Liquid Biopsy Biomarker

Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, Vol. 16 1551 Ivyspring International Publisher International Journal of Biological Sciences 2020; 16(9): 1551-1562. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.44024 Review Circulating tumor DNA as an emerging liquid biopsy biomarker for early diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring in hepatocellular carcinoma Xiaolin Wu1, Jiahui Li1, Asmae Gassa2, Denise Buchner1, Hakan Alakus1, Qiongzhu Dong3, Ning Ren4, Ming Liu5, Margarete Odenthal6, Dirk Stippel1, Christiane Bruns1, Yue Zhao1,7, and Roger Wahba1 1. Department of General, Visceral, Cancer and Transplantation Surgery, University Hospital of Cologne, Kerpener Straße 62, 50937, Cologne, Germany. 2. Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Heart Center, University Hospital of Cologne, Germany, Kerpener Straße 62, 5.937 Cologne, Germany. 3. Department of General Surgery, Huashan Hospital & Cancer Metastasis Institute & Institutes of Biomedical Sciences, Fudan University, 200032, Shanghai, P.R. China. 4. Liver Cancer Institute & Zhongshan Hospital; Department of Surgery, Institute of Fudan-Minhang Academic Health System, Minhang Branch, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, 200032, Shanghai, P.R. China. 5. Affiliated Cancer Hospital & Institute of Guangzhou Medical University; Key Laboratory of Protein Modification and Degradation, School of Basic Medical Sciences, 510095, Guangzhou, P.R. China. 6. Institute of Pathology, University Hospital of Cologne, 50937, Cologne, Germany. 7. Department of General, Visceral und Vascular Surgery, Otto-von-Guericke University, 39120, Magdeburg, Germany. Corresponding authors: Roger Wahba ([email protected]; Tel: +49-221-478-4803); Yue Zhao (yue.zhao @uk-koeln.de; Tel: +49-221-478-30601). © The author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). -

Cytomorphological Characterization of Individual Metastatic Tumor Cells from Gastrointestinal Cancer Patient Lymph Nodes with Imaging Flow Cytometry

Communication Cytomorphological Characterization of Individual Metastatic Tumor Cells from Gastrointestinal Cancer Patient Lymph Nodes with Imaging Flow Cytometry Marnie Winter 1 , Rachel Gibson 2, Andrew Ruszkiewicz 3 and Benjamin Thierry 1,* 1 Future Industries Institute and ARC Centre of Excellence in Convergent Bio-Nano Science and Technology, University of South Australia, Adelaide 5095, Australia; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Adelaide, Adelaide 5000, Australia; [email protected] 3 Department of Surgical Pathology, SA Pathology, Centre for Cancer Biology, University of South Australia, Adelaide 5000, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-8-8302-368 Received: 16 July 2019; Accepted: 19 September 2019; Published: 26 September 2019 Abstract: The presence or absence of tumor cells within patient lymph nodes is an important prognostic indicator in a number of cancer types and an essential element of the staging process. However, patients with the same pathological stage will not necessarily have the same outcome. Therefore, additional factors may aid in identifying patients at a greater risk of developing metastasis. In this proof of principle study, initially, spiked tumor cells in rat lymph nodes were used to mimic a node with a small cancer deposit. Next, human lymph nodes were obtained from cancer patients for morphological characterization. Nodes were dissociated with a manual tissue homogenizer and stained with fluorescent antibodies against CD45 and Pan-Cytokeratin and then imaging flow cytometry (AMNIS ImageStreamX Mark II) was performed. We show here that imaging flow cytometry can be used for the detection and characterization of small numbers of cancer cells in lymph nodes and we also demonstrate the phenotypical and morphological characterization of cancer cells in gastrointestinal cancer patient lymph nodes. -

Utility of Circulating Tumor DNA in Different Clinical Scenarios of Breast Cancer

cancers Review Utility of Circulating Tumor DNA in Different Clinical Scenarios of Breast Cancer Alexandra Mesquita 1,2,3,*, José Luís Costa 2,3 and Fernando Schmitt 2,3 1 Medical Oncology Department, Hospital Pedro Hispano, Unidade Local Saúde Matosinhos, 4464-513 Senhora da Hora, Portugal 2 Institute of Molecular Pathology and Immunology, University of Porto, 4200-135 Porto, Portugal; [email protected] (J.L.C.); [email protected] (F.S.) 3 Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, 4200-319 Porto, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 3 November 2020; Accepted: 14 December 2020; Published: 16 December 2020 Simple Summary: This review is focused on the concept of a specific type of “liquid biopsy”, circulating cell-free tumor DNA (ctDNA). It explores the advantages and limitations of using this technique and the latest advances of using it in different clinical scenarios of breast cancer: early, metastatic, and locally advanced disease. It provides the latest advances in this area applied to clinical research and clinical practice, as well as the importance of the collaboration between clinicians and laboratory teams to fully grasp the potential of ctDNA in a precision medicine era. Abstract: Breast cancer is a complex disease whose molecular mechanisms are not completely understood. Developing target therapies is a promising approach. Therefore, understanding the biological behavior of the tumor is a challenge. Tissue biopsy in the metastatic setting remains the standard method for diagnosis. Nevertheless, it has been associated with some disadvantages: It is an invasive procedure, it may not represent tumor heterogeneity, and it does not allow for treatment efficacy to be assessed or early recurrences to be detected. -

Perioperative Dynamic Changes in Circulating Tumor DNA in Patients

Published OnlineFirst August 22, 2019; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1213 Precision Medicine and Imaging Clinical Cancer Research Perioperative Dynamic Changes in Circulating Tumor DNA in Patients with Lung Cancer (DYNAMIC) Kezhong Chen1, Heng Zhao1, Yanbin Shi2, Fan Yang1, Lien Tu Wang2, Guannan Kang1, Yuntao Nie1, and Jun Wang1 Abstract Purpose: No study has investigated the precise periop- Results: Thirty-six patients showed detectable mutations erative dynamic changes in circulating tumor DNA in time A. The plasma ctDNA concentration showed a rapid (ctDNA) in any patients with early-stage cancer. This decreasing trend after radical tumor resection, with the aver- study (DYNAMIC) investigated perioperative dynamic age mutant allele fraction at times A, B, C, and D being changes in ctDNA and determined the appropriate detec- 2.72%, 2.11%, 1.14%, and 0.17%, respectively. The median tion time of ctDNA-based surveillance for surgical ctDNA half-life was 35.0 minutes. Patients with minimal patients with lung cancer. residual disease (MRD) detection had a significant slower Experimental Design: Consecutive patients who under- ctDNA half-life than those with negative MRD (103.2 min- went curative-intent lung resections were enrolled prospec- utes vs. 29.7 minutes, P ¼ 0.001). The recurrence-free survival tively (NCT02965391). Plasma samples were obtained at of patients with detectable and undetectable ctDNA concen- multiple prespecified time points including before surgery trations at time P1 was 528 days and 543 days, respectively (time A), during surgery after tumor resection (time B–time (P ¼ 0.657), whereas at time P2 was 278 days and 637 days, D), and after surgery (time P1–time P3). -

Clinical Relevance of Blood-Based Ctdna Analysis: Mutation Detection and Beyond

www.nature.com/bjc REVIEW ARTICLE Clinical relevance of blood-based ctDNA analysis: mutation detection and beyond Laura Keller1, Yassine Belloum1, Harriet Wikman1 and Klaus Pantel 1 Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) derived from tumours is present in the plasma of cancer patients. The majority of currently available studies on the use of this circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) deal with the detection of mutations. The analysis of cfDNA is often discussed in the context of the noninvasive detection of mutations that lead to resistance mechanisms and therapeutic and disease monitoring in cancer patients. Indeed, substantial advances have been made in this area, with the development of methods that reach high sensitivity and can interrogate a large number of genes. Interestingly, however, cfDNA can also be used to analyse different features of DNA, such as methylation status, size fragment patterns, transcriptomics and viral load, which open new avenues for the analysis of liquid biopsy samples from cancer patients. This review will focus on the new perspectives and challenges of cfDNA analysis from mutation detection in patients with solid malignancies. British Journal of Cancer (2021) 124:345–358; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-01047-5 BACKGROUND well understood and may not solely rely on the amount of dying Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) refers to extracellular DNA molecules cells. Not only the volume and metabolism of the tumour, but also (double-stranded DNA and mitochondrial DNA) originating from its rate of proliferation, have been positively correlated