180806 Chapter 7 SOUTH AUST CCL.Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Release

MEDIA RELEASE 7 February 2017 Premier awards Tennyson Medal at SACE Merit Ceremony The Premier of South Australia, the Hon. Jay Weatherill MP, awarded the prestigious Tennyson Medal for excellence in English Studies to 2016 Year 12 graduate, Ashleigh Jones at the SACE Merit Ceremony at Government House today. The ceremony, in its twenty-ninth year, saw 996 students awarded with 1302 subject merits for outstanding achievement in SACE Stage 2 subjects. Subject merits are awarded to students who gain an overall subject grade of A+ and demonstrate exceptional achievement in that subject. As part of the Merit Ceremony, His Excellency the Hon. Hieu Van Le AC, the Governor of South Australia, presented the following awards: Governor of South Australia Commendation for outstanding overall achievement in the SACE (twenty-five recipients in 2016) Governor of South Australia Commendation — Aboriginal Student SACE Award for the Aboriginal student with the highest overall achievement in the SACE Governor of South Australia Commendation – Excellence in Modified SACE Award for the student with an identified intellectual disability who demonstrates outstanding achievement exclusively through SACE modified subjects. The Tennyson Medal dates back to 1901 when the former Governor of South Australia, Lord Tennyson, established the Tennyson Medal to encourage the study of English literature. The long list of recipients includes the late John Bannon AO, 39th Premier of South Australia, who was awarded the medal in 1961. For her Year 12 English Studies, Ashleigh studied works by Henrik Ibsen (A Doll’s House), Zhang Yimou who directed Raise the Red Lantern, and Tennessee Williams (The Glass Menagerie). -

2017 Annual Report ABOUT DON

2017 Annual Report ABOUT DON Don Dunstan was one of Australia’s most charismatic, courageous, and visionary politicians; a dedicated reformer with a deep commitment to social justice, a true friend to the Aboriginal people and those newly arrived in Australia, and with a lifelong passion for the arts and education. He took positive steps to enhance the status of women. Most of his reforms have withstood the test of time and ‘We have faltered in our quest to many have been strengthened with time. Many of his reforms in sex discrimination, Aboriginal land rights provide better lives for all our and consumer protection were the first of their kind in citizens, rather than just for the Australia. talented, lucky groups. To regain He was a leading campaigner for immigration reform and our confidence in our power to was instrumental in the elimination of the White Australia shape the society in which we live, Policy. He was instrumental in social welfare and child protection reforms, consumer protection, Aboriginal and to replace fear and just land rights, urban planning, heritage protection, anti- coping with shared joy, optimism discrimination laws, abolition of capital punishment, and mutual respect, needs new environment protection and censorship. imagining and thinking and learning from what succeeds elsewhere.’ The Hon. Don Dunstan AC QC 2 CONTENTS NOTE: The digital copy of this report contains hyperlinks. These include the page numbers below, some images, and social media links throughout the report. 2 About Don 11 Art4Good Fund 4 Chair’s Report 12 Thinkers in Residence 5 Achievements 16 Adelaide Zero Project 6 Governance and Staff 19 Media Coverage Advisory Boards, Donate and Volunteer 7 Interns & Volunteers 20 8 Events 21 Financial Report 10 Scholarships 3 CHAIR’S REPORT In 2017 we celebrated 50 years since Don Dunstan first became Premier. -

Partnering in Action – Annual Report 2018

A brief history of the DISABILITY SERVICES SECTOR IN AUSTRALIA: 1992 – PRESENT DAY Lesley Chenoweth AO Emeritus Professor Griffith University ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was commissioned by Life Without Barriers. A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE DISABILITY SERVICES SECTOR IN AUSTRALIA: 1992 – PRESENT DAY | 1 CONTENTS List of figures and tables 2 8. Towards a National Disability Insurance Scheme 27 Glossary of terms 2 Australia 2020 27 1. Introduction 3 Productivity Commission Report 27 The brief 3 Money/Funding 28 Methodology 3 Implementation issues 29 How to read this report 4 9. Market Failure? 30 Overview of sections 5 10. Conclusion 31 Limitations of this report 5 References 32 2. Deinstitutionalisation 6 Appendix A 37 3. Shift to the community and supported living 10 Separation of housing and support 10 Appendix B 41 Supported living 11 Appendix C 44 Unmet need 12 Appendix D 45 4. Person-centred planning 14 Appendix E 46 5. Local Area Coordination 16 6. Marketisation 20 7. Abuse, Violence and Restrictive practices 23 Institutionalised settings 23 Complex needs and challenging behaviour 24 Restrictive practices 24 Incarceration and Domestic Violence 26 2 | A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE DISABILITY SERVICES SECTOR IN AUSTRALIA: 1992 – PRESENT DAY LIST OF FIGURES GLOSSARY OF TERMS AND TABLES CSDA Commonwealth/State Disability Agreements Figure 1 Demand vs funding available 12 DSA Disability Services Act 1986 Table 1 Restrictive practices DDA Disability Discrimination Act 1992 authorisation summary 25 CAA Carers Association of Australia NGO Non-Government Organisation PDAA People with Disabilities Australia DSSA Disability and Sickness Support Act 1991 | 3 1. INTRODUCTION The brief Methodology Life Without Barriers requested an historical overview The approach to the research consisted of several distinct of the national disability sector from approximately 1992 but interrelated phases: to present including: • Key federal and state-based legislation and policies 1. -

Policy Life Cycle Analysis of Three Australian State-Level Public

Article Journal of Development Policy Life Cycle Policy and Practice 6(1) 9–35, 2021 Analysis of Three © 2021 Aequitas Consulting Pvt. Ltd. and SAGE Australian State-level Reprints and permissions: in.sagepub.com/journals-permissions-india Public Policies: DOI: 10.1177/2455133321998805 Exploring the journals.sagepub.com/home/jdp Political Dimension of Sustainable Development Kuntal Goswami1,2 and Rolf Gerritsen1 Abstract This article analyses the life cycle of three Australian public policies (Tasmania Together [TT], South Australia’s Strategic Plan [SASP,] and Western Australia’s State Sustainability Strategy [WA’s SSS]). These policies were formulated at the state level and were structured around sustainable development concepts (the environmental, economic, and social dimensions). This study highlights contexts that led to the making of these public policies, as well as factors that led to their discontinuation. The case studies are based on analysis of parliamentary debates, state governments’ budget reports, public agencies’ annual reports, government media releases, and stakeholders’ feedback. The empirical findings highlight the importance of understanding the political dimension of sustainable development. This fact highlights the need to look beyond the traditional three-dimensional view of sustainability when assessing the success (or lack thereof) of sustainable development policies. Equally important, the analysis indicates that despite these policies’ limited success (and even one of these policies not being implemented at all), sustainability policies can have a legacy beyond their life cycle. Hence, the evaluation of these policies is likely to provide insight into the process of policymaking. 1 Charles Darwin University (CDU), Alice Springs, Northern Territory, Australia. 2 Australian Centre for Sustainable Development Research & Innovation (ACSDRI), Adelaide, South Australia, Australia. -

Vietnamese Family Reunion in Australia 1983 – 2007 Bianca Lowe

Vietnamese Family Reunion in Australia 1983 – 2007 Bianca Lowe Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2016 Graduate School of Historical and Philosophical Studies The University of Melbourne ABSTRACT This thesis explores the reunification of Vietnamese families in Australia through the family reunion program from 1983 to 2007. Focusing upon these key years in the program, and building upon substantial existing research into the settlement of Vietnamese refugees in Australia, this dissertation adds to the knowledge of Vietnamese-Australian migration by focusing on the hitherto neglected story of family reunion. It offers an account of the process and circumstances by which Vietnamese families attempted to reunite and establish new lives in Australia, following the Vietnam War. Drawing upon analysis of political debate and interviews with Vietnamese families, this thesis provides an overview of years that challenged traditional narratives of national identity and of the composition and character of the ‘family of the nation’. During this period, the Australian Government facilitated the entry of large numbers of Asian migrants, which represented a fundamental shift in the composition of the national community. Analysis of political commentary on Vietnamese family reunion reveals tensions between the desire to retain traditional conceptions of Australian national identity and the drive to present Australia as an adaptable and modern country. The early chapters of this thesis examine political debate in the Australian Parliament about the family reunion program. They note differing emphases across the Hawke-Keating Labor Government (1983-1996) and Howard Liberal-National Coalition Government (1996-2007), but also similarities that underline the growing adherence to economic rationalism and the effect this had on the broad design of the program. -

Legislative Assembly Hansard 1985

Queensland Parliamentary Debates [Hansard] Legislative Assembly TUESDAY, 27 AUGUST 1985 Electronic reproduction of original hardcopy Papers 27 August 1985 141 TUESDAY, 27 AUGUST 1985 Mr SPEAKER (Hon. J. H. Wamer, Toowoomba South) read prayers and took the chair at 11 a.m. ASSENT TO BILL Appropriation Bill (No. 1) Mr SPEAKER: I have to report that on 23 August 1985 I presented to His Excellency the Govemor Appropriation Bill (No. 1) for the Royal Assent and that His Excellency was pleased, in my presence, to subscribe his assent thereto in the name and on behalf of Her Majesty. PETITIONS The Clerk announced the receipt of the following petitions— Minimum Penalties for Child Abuse From Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen (2 637 signatories) praying that the Parliament of Queensland wiU set down minimum penalties for child abuse. Third-party Insurance Premiums From Mr Warburton (40 152 signatories) praying that the Parliament of Queensland will revoke the recent increases in third-party insurance and ensure that future increases be determined after public hearing. Petitions received. PAPERS The following papers were laid on the table— Proclamations under— Foresty Act 1959-1984 Constmction Safety Act Amendment Act 1985 State Enterprises Acts Repeal Act 1983 Eraser Island Public Access Act 1985 Orders in Council under— Legislative Assembly Act 1867-1978 Forestry Act 1959-1984 Harbours Act 1955-1982 and the Statutory Bodies Financial Arrangements Act 1982-1984 Workers' Compensation Act 1916-1983 Auctioneers and Agents Act 1971-1981 Supreme Court Act of -

Sixteen Years of Labor Government in South Australia, 2002-2018

AUSTRALASIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW Parliament in the Periphery: Sixteen Years of Labor Government in South Australia, 2002-2018* Mark Dean Research Associate, Australian Industrial Transformation Institute, Flinders University of South Australia * Double-blind reviewed article. Abstract This article examines the sixteen years of Labor government in South Australia from 2002 to 2018. With reference to industry policy and strategy in the context of deindustrialisation, it analyses the impact and implications of policy choices made under Premiers Mike Rann and Jay Weatherill in attempts to progress South Australia beyond its growing status as a ‘rustbelt state’. Previous research has shown how, despite half of Labor’s term in office as a minority government and Rann’s apparent disregard for the Parliament, the executive’s ‘third way’ brand of policymaking was a powerful force in shaping the State’s development. This article approaches this contention from a new perspective to suggest that although this approach produced innovative policy outcomes, these were a vehicle for neo-liberal transformations to the State’s institutions. In strategically avoiding much legislative scrutiny, the Rann and Weatherill governments’ brand of policymaking was arguably unable to produce a coordinated response to South Australia’s deindustrialisation in a State historically shaped by more interventionist government and a clear role for the legislature. In undermining public services and hollowing out policy, the Rann and Wethearill governments reflected the path dependency of responses to earlier neo-liberal reforms, further entrenching neo-liberal responses to social and economic crisis and aiding a smooth transition to Liberal government in 2018. INTRODUCTION For sixteen years, from March 2002 to March 2018, South Australia was governed by the Labor Party. -

Melbourne Suburb of Northcote

ON STAGE The Autumn 2012 journal of Vol.13 No.2 ‘By Gosh, it’s pleasant entertainment’ Frank Van Straten, Ian Smith and the CATHS Research Group relive good times at the Plaza Theatre, Northcote. ‘ y Gosh, it’s pleasant entertainment’, equipment. It’s a building that does not give along the way, its management was probably wrote Frank Doherty in The Argus up its secrets easily. more often living a nightmare on Elm Street. Bin January 1952. It was an apt Nevertheless it stands as a reminder The Plaza was the dream of Mr Ludbrook summation of the variety fare offered for 10 of one man’s determination to run an Owen Menck, who owned it to the end. One years at the Plaza Theatre in the northern independent cinema in the face of powerful of his partners in the variety venture later Melbourne suburb of Northcote. opposition, and then boldly break with the described him as ‘a little elderly gentleman The shell of the old theatre still stands on past and turn to live variety shows. It was about to expand his horse breeding interests the west side of bustling High Street, on the a unique and quixotic venture for 1950s and invest in show business’. Mr Menck was corner of Elm Street. It’s a time-worn façade, Melbourne, but it survived for as long as consistent about his twin interests. Twenty but distinctive; the Art Deco tower now a many theatres with better pedigrees and years earlier, when he opened the Plaza as a convenient perch for telecommunication richer backers. -

Ministerial Careers and Accountability in the Australian Commonwealth Government / Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis

AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Ministerial careers and accountability in the Australian Commonwealth government / edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis. ISBN: 9781922144003 (pbk.) 9781922144010 (ebook) Series: ANZSOG series Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Politicians--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Ethical behavior. Political ethics--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Public opinion. Australia--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--Public opinion. Other Authors/Contributors: Dowding, Keith M. Lewis, Chris. Dewey Number: 324.220994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents 1. Hiring, Firing, Roles and Responsibilities. 1 Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis 2. Ministers as Ministries and the Logic of their Collective Action . 15 John Wanna 3. Predicting Cabinet Ministers: A psychological approach ..... 35 Michael Dalvean 4. Democratic Ambivalence? Ministerial attitudes to party and parliamentary scrutiny ........................... 67 James Walter 5. Ministerial Accountability to Parliament ................ 95 Phil Larkin 6. The Pattern of Forced Exits from the Ministry ........... 115 Keith Dowding, Chris Lewis and Adam Packer 7. Ministers and Scandals ......................... -

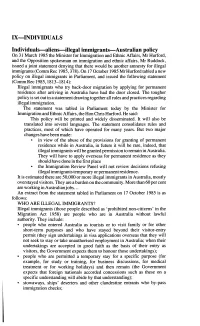

IX-INDIVIDUALS Individuals-Aliens-Illegal Immigrants

IX-INDIVIDUALS Individuals-aliens-illegal immigrants-Australian policy On 3 1 March 1985 the Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs, Mr Hurford, and the Opposition spokesman on immigration and ethnic affairs, Mr Ruddock, issued a joint statement denying that there would be another amnesty for illegal immigrants (Comm Rec 1985,378). On 17 October 1985 Mr Hurford tabled anew policy on illegal immigrants in Parliament, and issued the following statement (CommRec 1985,1813-1814): Illegal immigrants who try back-door migration by applying for permanent residence after arriving in Australia have had the door closed. The tougher policy is set out in a statement drawing together all rules and practices regarding illegal immigration. The statement was tabled in Parliament today by the Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs, the Hon Chris Hurford. He said: This policy will be printed and widely disseminated. It will also be translated into several languages. The statement consolidates rules and practices, most of which have operated for many years. But two major changes have been made: in view of the abuse of the provisions for granting of permanent residence while in Australia, in future it will be rare, indeed, that illegal immigrants will be granted permission to remain in Australia. They will have to apply overseas for permanent residence as they should have done in the first place the Immigration Review Panel will not review decisions refusing illegal immigrants temporary or permanent residence. It is estimated there are 50,000 or more illegal immigrants in Australia, mostly overstayed visitors. They are a burden on the community. -

Asylum Seekers and Australian Politics, 1996-2007

ASYLUM SEEKERS AND AUSTRALIAN POLITICS, 1996-2007 Bette D. Wright, BA(Hons), MA(Int St) Discipline of Politics & International Studies (POLIS) School of History and Politics The University of Adelaide, South Australia A Thesis Presented to the School of History and Politics In the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Contents DECLARATION ................................................................................................................... i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................. ii ABSTRACT ......................................................................................................................... iii INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. v CHAPTER 1: CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK .................................................................. 1 Sovereignty, the nation-state and stateless people ............................................................. 1 Nationalism and Identity .................................................................................................. 11 Citizenship, Inclusion and Exclusion ............................................................................... 17 Justice and human rights .................................................................................................. 20 CHAPTER 2: REFUGEE ISSUES & THEORETICAL REFLECTIONS ......................... 30 Who -

Volume 40, Number 1 the ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Law.Adelaide.Edu.Au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD

Volume 40, Number 1 THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW law.adelaide.edu.au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD The Honourable Professor Catherine Branson AC QC Deputy Chancellor, The University of Adelaide; Former President, Australian Human Rights Commission; Former Justice, Federal Court of Australia Emeritus Professor William R Cornish CMG QC Emeritus Herchel Smith Professor of Intellectual Property Law, University of Cambridge His Excellency Judge James R Crawford AC SC International Court of Justice The Honourable Professor John J Doyle AC QC Former Chief Justice, Supreme Court of South Australia Professor John V Orth William Rand Kenan Jr Professor of Law, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Professor Emerita Rosemary J Owens AO Former Dean, Adelaide Law School The Honourable Justice Melissa Perry Federal Court of Australia Emeritus Professor Ivan Shearer AM RFD Sydney Law School The Honourable Margaret White AO Former Justice, Supreme Court of Queensland Professor John M Williams Dame Roma Mitchell Chair of Law and Former Dean, Adelaide Law School ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Editors Associate Professor Matthew Stubbs and Dr Michelle Lim Book Review and Comment Editor Dr Stacey Henderson Associate Editors Charles Hamra, Kyriaco Nikias and Azaara Perakath Student Editors Joshua Aikens Christian Andreotti Mitchell Brunker Peter Dalrymple Henry Materne-Smith Holly Nicholls Clare Nolan Eleanor Nolan Vincent Rocca India Short Christine Vu Kate Walsh Noel Williams Publications Officer Panita Hirunboot Volume 40 Issue 1 2019 The Adelaide Law Review is a double-blind peer reviewed journal that is published twice a year by the Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide. A guide for the submission of manuscripts is set out at the back of this issue.