Bringing China's Best and Brightest Back Home

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Quint : an Interdisciplinary Quarterly from the North 1

the quint : an interdisciplinary quarterly from the north 1 Editorial Advisory Board the quint volume ten issue two Moshen Ashtiany, Columbia University Ying Kong, University College of the North Brenda Austin-Smith, University of Martin Kuester, University of Marburg an interdisciplinary quarterly from Manitoba Ronald Marken, Professor Emeritus, Keith Batterbe. University of Turku University of Saskatchewan the north Donald Beecher, Carleton University Camille McCutcheon, University of South Melanie Belmore, University College of the Carolina Upstate ISSN 1920-1028 North Lorraine Meyer, Brandon University editor Gerald Bowler, Independent Scholar Ray Merlock, University of South Carolina Sue Matheson Robert Budde, University Northern British Upstate Columbia Antonia Mills, Professor Emeritus, John Butler, Independent Scholar University of Northern British Columbia David Carpenter, Professor Emeritus, Ikuko Mizunoe, Professor Emeritus, the quint welcomes submissions. See our guidelines University of Saskatchewan Kyoritsu Women’s University or contact us at: Terrence Craig, Mount Allison University Avis Mysyk, Cape Breton University the quint Lynn Echevarria, Yukon College Hisam Nakamura, Tenri University University College of the North Andrew Patrick Nelson, University of P.O. Box 3000 Erwin Erdhardt, III, University of Montana The Pas, Manitoba Cincinnati Canada R9A 1K7 Peter Falconer, University of Bristol Julie Pelletier, University of Winnipeg Vincent Pitturo, Denver University We cannot be held responsible for unsolicited Peter Geller, -

Roles of Parents' Capitals in Children's Educational

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2018 ROLES OF PARENTS’ CAPITALS IN CHILDREN’S EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES Liping Pan University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Pan, Liping. (2018). ROLES OF PARENTS’ CAPITALS IN CHILDREN’S EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES. University of the Pacific, Dissertation. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/3130 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 ROLES OF PARENTS‘ CAPITALS IN CHILDREN‘S EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES by Liping Pan. A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Gladys L. Benerd School of Education Curriculum and Instruction University of the Pacific Stockton, California 2018 2 ROLES OF PARENTS‘ CAPITALS IN CHILDREN‘S EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES by Liping Pan. APPROVED BY: Dissertation Advisor: Ronald Hallett, Ph.D. Committee Member: Delores McNair, Ed.D Committee Member: Marcia Hernandez, Ph. D. Department Chair: Linda Skrla, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate School: Thomas Naehr, Ph.D. 3 ROLES OF PARENTS‘ CAPITALS IN CHILDREN‘S EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIE Copyright 2018 by Liping Pan. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I was born in a countryside village, and grew in a natural and wild way. I had never ever thought of going to a college even before my senior high school years. -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

How Shanghai Does It

How Shanghai Does ItHow DIRECTIONS IN DEVELOPMENT Human Development Liang, Kidwai, and Zhang Liang, How Shanghai Does It Insights and Lessons from the Highest-Ranking Education System in the World Xiaoyan Liang, Huma Kidwai, and Minxuan Zhang How Shanghai Does It DIRECTIONS IN DEVELOPMENT Human Development How Shanghai Does It Insights and Lessons from the Highest-Ranking Education System in the World Xiaoyan Liang, Huma Kidwai, and Minxuan Zhang © 2016 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 19 18 17 16 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpreta- tions, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

3/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 30 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 34 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 36 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 39 Taiwan Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 41 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 43 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 3/2006 Dep.Dir.: CHINESE COMMUNIST Li Jianhua 03/07 PARTY Li Zhiyong 05/07 The Main National Ouyang Song 05/08 Shen Yueyue (f) CCa 03/01 Leadership of the Sun Xiaoqun 00/08 Wang Dongming 02/10 CCP CC General Secretary Zhang Bolin (exec.) 98/03 PRC Hu Jintao 02/11 Zhao Hongzhu (exec.) 00/10 Zhao Zongnai 00/10 Liu Jen-Kai POLITBURO Sec.-Gen.: Li Zhiyong 01/03 Standing Committee Members Propaganda (Publicity) Department Hu Jintao 92/10 Dir.: Liu Yunshan PBm CCSm 02/10 Huang Ju 02/11 -

Exploring Chinese Education in Beijing in June 2016, a Delegation

Exploring Chinese Education in Beijing In June 2016, a delegation of nine school principals from different parts of Finland visited Beijing, exploring Chinese education and experiencing Chinese culture. This delegation was organized by the Confucius Institute and led by Kauko Laitinen, former Director of the Institute. During their one-week stay in Beijing, the delegation visited the Confucius Institute Headquarters, two high schools and two universities. At the Confucius Institute Headquarters, the principals visited the Chinese Culture Exhibition Hall. They excitedly experienced Chinese calligraphy and tried on the Chinese traditional costumes, for the first time in their life. After learning about the development of the Chinese teaching materials and network resources, the principals showed great interest in Finnish-Chinese textbooks and expressed their hope of offering Chinese courses in Finnish high schools. Pic. 001 At Hanban /Confucius Institute Headquarters Pic. 002 Experiencing Chinese costumes at Chinese Culture Exhibition Hall The principals were well received at both Renmin University of China (RUC) and Beijing Normal University (BNU). They got opportunities to talk with university leaders and students and teachers, learning about higher education in China. They also toured around the campuses, visited libraries and teaching buildings. Pic. 003 Visiting RUC library Pic. 004 Meeting local principals and teachers at BNU During their visits to the High School Affiliated to Renmin University of China, and Shijingshan District Middle School Affiliated to Beijing Institute of Education, the principals exchanged with the local principals and teachers their views on the educational systems, the curriculums and students' learning styles in the two countries. At the same time, the two sides also explored the possibilities for further cooperation and exchanges in the future. -

Deepen Friendship, Seek Cooperation and Mutual Development

ISSUE 3 2009 NPCNational People’s Congress of China Deepen friendship, seek cooperation and mutual development Chinese Premier’s 60 hours in Copenhagen 3 2 Wang Zhaoguo (first from right), member of Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee and vice chairman of the NPC Standing Committee, holds a talk with the acting chairman of the National Provincial Affairs Committee of South Africa on November 3rd, 2009. Li Jianmin 3 Contents Special Report Hot Topics Deputy 6 12 20 Deepen friendship, seek Food safety, a long journey Mao Fengmei speaks on his 17 cooperation and mutual ahead of China years of NPC membership development COVER: Low-carbon measures are to be 16 taken during the upcoming Shanghai World 22 Expo 2010. Construction of the China Pavil- NPC oversees how governments An interview with 11th NPC deputy ion was completed on February 8. At the top spend 4 trillion stimulus money of the oriental crown shaped pavilion, four Juma Taier Mawla Hajj solar panels will collect sunlight and turn so- lar energy into electricity inside. CFP 4 NPC Adviser-In-General: Li Jianguo Advisers: Wang Wanbin, Yang Jingyu, Jiang Enzhu, Qiao Xiaoyang, Nan Zhenzhong, Li Zhaoxing Lu Congmin, Wang Yingfan, Ji Peiding, Cao Weizhou Chief of Editorial Board: Li Lianning Members of Editorial Board: Yin Zhongqing, Xin Chunying, Shen Chunyao, Ren Maodong, Zhu Xueqing, Kan Ke, Peng Fang, Wang Tiemin, Yang Ruixue, Gao Qi, Zhao Jie Xu Yan Chief Editor: Wang Tiemin Vice-Chief Editors: Gao Qi, Xu Yan Executive Editor: Xu Yan Copy Editor: Zhang Baoshan, Jiang Zhuqing Layout Designers: Liu Tingting, Chen Yuye Wu Yue General Editorial Office Address: 23 Xijiaominxiang,Xicheng District Beijing 100805,P.R.China Tel: (86-10)6309-8540 (86-10)8308-4419 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN 1674-3008 CN 11-5683/D Price:RMB35 Edited by The People’s Congresses Journal Published by The People’s Congresses Journal Printed by C&C Joint Printing Co.,(Beijing) Ltd. -

Westlake Youth Forum 2019 第四届西湖青年论坛

Westlake Youth Forum 2019 第四届西湖青年论坛 Call for Application Zhejiang University and China Medical Board (CMB) joint hands to host the 4th Westlake Youth Forum in 2019, with facilitation from China Health Policy and Management Society (CHPAMS). The Organizing Committee of the Forum is pleased to invite applications for participating in the Forum. The Forum provides a platform for young scholars worldwide to build up academic network, to exchange scientific thoughts and research experience, to communicate with senior scholars and policymakers, and to advance health policy in China. The 2019 Forum will be a three-day event for young researchers and practitioners in health policy and system on June 10-13, 2019 at Zhejiang University, China. Westlake Youth Forum: • When: June 10-13, 2019 • Where: Zhejiang University International Campus, Haining, Zhejiang Province, China • Preliminary Program: June 10. Registration and social activities June 11-12. Academic sessions and events of the Westlake Youth Forum June 13. Field visit What will be provided to all participants: • Local expenses including meals, accommodation, and local transportation in Haining, Zhejiang; • Networking with world-class academic leaders and young scholars from inside and outside of China; • Networking with Chinese academic leaders to explore your career opportunities in China; • Presenting your research and communicating with academic leaders and peers at the Forum. Who can apply for the participation (Eligibility)? • Scholars under 45 years old from CMB OC eligible schools (see Appendix I), OC awardees preferred but not required; • Working in public health related fields; • Having the interest to build collaboration with academic and research institutions, governmental departments, and corporations in China. -

TRANSITION from ELITE to MASS HIGHER EDUCATION in CHINA By

TRANSITION FROM ELITE TO MASS HIGHER EDUCATION IN CHINA by YANQINGXUE submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF EDUCATION in the subject COMPARATIVE EDUCATION at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF S G PRETORIUS ~ t I JUNE2001 f II I Student number: 3247-339-7 I declare that TRANSITION FROM ELITE TO MASS HIGHER EDUCATION IN CHINA is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. -LL _j .~ti ... ~ .... ~(./.~/.~/ .. SIGNATURE DATE (MR YQXUE) Acknowledgements I wish to convey my sincere thanks to Professor S. G. Pretorius, my supervisor, for his capable, patient and friendly guidance; Appreciation is also extended to Mrs. Mattie Verwey for her kind helpfulness in many ways; To Professor E.M. Lemmer for language editing and checking the qualitative research; To Professor Y. J. Wang and Professor G.D. Kamper for their warm assistance; To all the informants for their time and energy;. To UNISA library staff for their high quality services; At last, my dedication to Jin and Y angyang, my dear wife and son, for their love and encouragement. SUMMARY The research focuses on the strategies for the transition from elite to mass higher education in China. The expansion of Chinese higher education has accelerated since 1998. The Chinese government plans to increase its gross enrolment rate in higher education to 15% by 2010. According to Trow's (1974:63) phase development theories, this increase of enrolment would lead to fundamental changes in higher education. -

China's Special Education: a Comparative Analysis

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 361 947 EC 302 414 AUTHOR Mu, Keli; And Others TITLE China's Special Education: A Comparative Analysis. PUB DATE Apr 93 NOTE 9p.; Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the Council for Exceptional Children (71st, San Antonio, TX, April 5-9, 1993). PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) Speeches /Conference Papers (150) Tests/Evaluation Instruments (160) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PCO1 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Attendance; Compulsory Education; *Delivery Systems; Differences; *Disabilities; Early Intervention; Educational History; Educational Legislation; Educational Needs; *Educational Practices; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; Higher Education; Incidence; Inservice Teacher Education; Mainstreaming; Parent School Relationship; Regional Characteristics; *Special Education; Teacher Exchange Programs; Teacher Shortage; Vocational Education IDENTIFIERS *China ABSTRACT This paper, written in outline form, summarizes the history and current situation of special education in China. The paper begins by listing milestones in Chinese special education from 200 B.C. to 1990 A.D. and noting that currently there are an estimated 6,500,000 children (ages 7-15, with disabilities, of whom 70,000 are being served in special classes and special schools. Contemporary legislation pertaining to special education are noted, followed by a description of current education practices in the areas of regular education, special schools, higher education, and inservice teacher training. Current examples of educational research are also described, including experiments in service delivery options (such as mainstreaming), early intervention and education, and parent/school collaboration. Activities in the areas of international exchange are briefly noted. Major problems identified include the following:(1) low school attendance rate by children with disabilities, (2) large regional variances in school attendance, (3) limited vocational training options, and (4) shortage of teachers. -

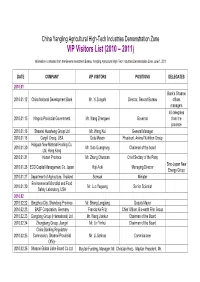

VIP Visitors List (2010 – 2011)

China Yangling Agricultural High-Tech Industries Demonstration Zone VIP Visitors List (2010 – 2011) Information is obtained from the General Investment Bureau, Yangling Agricultural High-Tech Industries Demonstration Zone, June 1, 2011 DATE COMPANY VIP VISITORS POSITIONS DELEGATES 2010.01 Bank's Shaanxi 2010.01.12 China National Development Bank Mr. Yi Zongshi Director, Second Bureau offices managers 40 delegates 2010.01.15 Ningxia Provincial Government Mr. Wang Zhengwei Governor from the province 2010.01.16 Shaanxi Huasheng Group Ltd Mr. Wang Kui General Manager 2010.01.18 Cargill Group, USA Dula Muson President, Animal Nutrition Group Haiguan New Material Holding Co. 2010.01.20 Mr. Xiao Guangrong Chairman of the board Ltd, Hong Kong 2010.01.21 Hunan Province Mr. Zhang Chunxian Chief Sectary of the Party Sino-Japan New 2010.01.26 ECO Capital Management Co. Japan Koji Aoki Managing Director Energy Group 2010.01.27 Department of Agriculture, Thailand Somsak Minister Environmental Microbial and Food 2010.01.30 Mr. Luo Yaguang Senior Scientist Safety Laboratory, USA 2010.02 2010.02.22 Bingzhou City, Shandong Province Mr. Shang Longjiang Deputy Mayor 2010.02.23 BASF Corporation, Germany Francis Ka Fritz Chief Officer, Bio-earth Film Group 2010.02.23 Dongfang Group (International) Ltd Mr. Wang Jiankun Chairman of the Board 2010.02.24 Zhengbang Group, Jiangxi Mr. Lin Yinhui Chairman of the Board China Banking Regulatory 2010.02.25 Commission, Shaanxi Provincial Mr. Li Jianhua Commissioner Office 2010.02.26 Shaanxi Global Jiahe Board Co Ltd Mayfair Funding, Manager: Mr. Christian Herz,Mayfair President: Mr. Rainer Kutzner (Germany), PBH Ltd President: Mr.