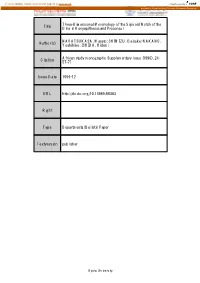

Taphonomic and Site Formation of Two Early Miocene Sites on Rusinga Island, Kenya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tracker June/July 2014

KENYA MUSEUM SOCIETY Tracker June/July 2014 Joy Adamson Exhibition Photo by Ebrahim Mwangi, NMK AV Dept Kenya Museum Society P.O. Box 40658 - 00100 Nairobi, Kenya [email protected] www.kenyamuseumsociety.org Tel: 3743808/2339158 (Direct) kenyamuseumsociety Tel: 8164134/5/6 ext 2311 Cell: 0724255299 @museumsociety DRY ASSOCIATES LTD Investment Group Offering you a rainbow of opportunities ... Wealth Management Since 1994 Dry Associates House Brookside Grove, Westlands, Nairobi Tel: +254 (20) 445-0520/1 +254 (20) 234-9651 Mobile(s): 0705799971/0705849429/ 0738253811 June/July 2014 Tracker www.dryassociates.com2 NEWS FROM NMK Joy Adamson Exhibition New at Nairobi National Museum he historic collections of Joy Adamson’s portraits of the peoples of Kenya as well as her botanical and wildlife paintings are once again on view at the TNairobi National Museum. This exhibi- tion includes 50 of Joy’s intriguing portraits and her beautiful botanicals and wildlifeThe exhibition,illustrations funded that are by complementedKMS was officially by related opened objects on May from 19. the muse- um’sVisit ethnographic the KMS shop and where scientific cards collections. featuring some of the portraits are available as is the book, Peoples of Kenya; KMS members are entitled to a 5 per cent dis- count on books. The museum is open seven days a week from 9.30 am to 5.30 pm. Joy Adamson Exhibition Photo by Ebrahim Mwangi, NMK AV Dept June/July 2014 Tracker 3 KMS EASTER SAFARI 18Tsavo - 21 APRIL West 2014 National Park By James Reynolds he Kenya Museum Society's Easter trip saw organiser Narinder Heyer Ta simple but tasty snack in Makindu's Sikh temple, the group entered lead a group of 21 people in 7 vehicles to Tsavo West National Park. -

Download Full Article in PDF Format

Dryopithecins, Darwin, de Bonis, and the European origin of the African apes and human clade David R. BEGUN University of Toronto, Department of Anthropology, 19 Russell Street, Toronto, ON, M5S 2S2 (Canada) [email protected] Begun R. D. 2009. — Dryopithecins, Darwin, de Bonis, and the European origin of the African apes and human clade. Geodiversitas 31 (4) : 789-816. ABSTRACT Darwin famously opined that the most likely place of origin of the common ancestor of African apes and humans is Africa, given the distribution of its liv- ing descendents. But it is infrequently recalled that immediately afterwards, Darwin, in his typically thorough and cautious style, noted that a fossil ape from Europe, Dryopithecus, may instead represent the ancestors of African apes, which dispersed into Africa from Europe. Louis de Bonis and his collaborators were the fi rst researchers in the modern era to echo Darwin’s suggestion about apes from Europe. Resulting from their spectacular discoveries in Greece over several decades, de Bonis and colleagues have shown convincingly that African KEY WORDS ape and human clade members (hominines) lived in Europe at least 9.5 million Mammalia, years ago. Here I review the fossil record of hominoids in Europe as it relates to Primates, Dryopithecus, the origins of the hominines. While I diff er in some details with Louis, we are Hispanopithecus, in complete agreement on the importance of Europe in determining the fate Rudapithecus, of the African ape and human clade. Th ere is no doubt that Louis de Bonis is Ouranopithecus, hominine origins, a pioneer in advancing our understanding of this fascinating time in our evo- new subtribe. -

Unravelling the Positional Behaviour of Fossil Hominoids: Morphofunctional and Structural Analysis of the Primate Hindlimb

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en Doctorado en Biodiversitat Facultad de Ciènces Tesis doctoral Unravelling the positional behaviour of fossil hominoids: Morphofunctional and structural analysis of the primate hindlimb Marta Pina Miguel 2016 Memoria presentada por Marta Pina Miguel para optar al grado de Doctor por la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, programa de doctorado en Biodiversitat del Departamento de Biologia Animal, de Biologia Vegetal i d’Ecologia (Facultad de Ciències). Este trabajo ha sido dirigido por el Dr. Salvador Moyà Solà (Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont) y el Dr. Sergio Almécija Martínez (The George Washington Univertisy). Director Co-director Dr. Salvador Moyà Solà Dr. Sergio Almécija Martínez A mis padres y hermana. Y a todas aquelas personas que un día decidieron perseguir un sueño Contents Acknowledgments [in Spanish] 13 Abstract 19 Resumen 21 Section I. Introduction 23 Hominoid positional behaviour The great apes of the Vallès-Penedès Basin: State-of-the-art Section II. Objectives 55 Section III. Material and Methods 59 Hindlimb fossil remains of the Vallès-Penedès hominoids Comparative sample Area of study: The Vallès-Penedès Basin Methodology: Generalities and principles Section IV. -

Title Three-Dimensional Morphology of the Sigmoid Notch of The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Three-Dimensional Morphology of the Sigmoid Notch of the Title Ulna in Kenyapithecus and Proconsul NAKATSUKASA, Masato; SHIMIZU, Daisuke; NAKANO, Author(s) Yoshihiko; ISHIDA, Hidemi African study monographs. Supplementary issue (1996), 24: Citation 57-71 Issue Date 1996-12 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/68383 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl. 24: 57-71, December 1996 57 THREE-DIMENSIONAL MORPHOLOGY OF THE SIGMOID NOTCH OF THE ULNA IN KENYAPITHECUS AND PROCONSUL Masato Nakatsukasa Daisuke Shimizu Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Faculty of Science, Kyoto University Yoshihiko Nakano Department of Biological Anthropology, Faculty of Human Sciences, Osaka University Hidemi Ishida Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Faculty of Science, Kyoto University ABSTRACT The three-dimensional (3-D) morphology of the sigmoid notch was examined in Kenyapithecus, Proconsul, and several living anthropoids by using an automatic 3-D digitizer. It was revealed that Kenyapithecus and Proconsul exhibit a very similar morphology of the dis tal region of the sigmoid notch; including the absence of a median keel and a downward sloped coronoid process. In addition, the proxilnal region of the sigmoid notch is curved more acutely relative to the distal region in Proconsul. This morphological complex is unique and not found in the examined living primates. The benefits of 3-D morphometries are discussed. Key Words: Kenyapithecus, Proconsul, sigmoid notch, three-dimensional morphometrics, ulna. INTRODUCTION Recently, automatic three-dimensional (3-0) digitizers have become more fre quently to be used for biometrics. -

Thesis Ch1 Nile Perch and HIV Among the Suba of Lake Victoria

Towards an Anthropology of Organic Health 1 Salmen, Charles 2009. "Towards an Anthropology of Organic Health: The Relational Fields of HIV/AIDS among the Suba of Lake Victoria". Distinguished Masters Dissertation, Oxford Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology. Chapter 1 Introduction: The smallest AIDS virus takes you from sex to the unconscious, then to Africa, tissue cultures, DNA and San Francisco, but the analysts, thinkers, journalists and decision-makers will slice the delicate network traced by the virus for you into tidy compartments where you will find only science, only economy, only social phenomena, only local news, only sentiment, only sex….To shuttle back and forth, we rely on the notion of translation, or network. More supple than the notion of system, more historical than the notion of structure, more empirical than the notion of complexity, the idea of network is the Ariadne’s thread of these interwoven stories. -Bruno Latour,, from We Have Never Been Modern. ♣ In the decades since the inception of our discipline, medical anthropology has contributed a diverse corpus of ethnographic research blurring the lines between the biological, social, and ecological factors that shape wellbeing and sickness. Yet, within the biomedical institutions that direct global health today, disease and health continue to be understood primarily in physiological terms. Numerous compelling arguments for biocultural synthesis continue to fall on deaf ears due in large part, I assert, to the axiomatic notion in biomedicine that an individual human being represents a discrete organism. An emerging consortium of anthropologists, systems biologists, and human ecologists, however, suggest that the distinction between human organism and human ecosystem is inherently ambiguous. -

Kenyan Stone Age: the Louis Leakey Collection

World Archaeology at the Pitt Rivers Museum: A Characterization edited by Dan Hicks and Alice Stevenson, Archaeopress 2013, pages 35-21 3 Kenyan Stone Age: the Louis Leakey Collection Ceri Shipton Access 3.1 Introduction Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey is considered to be the founding father of palaeoanthropology, and his donation of some 6,747 artefacts from several Kenyan sites to the Pitt Rivers Museum (PRM) make his one of the largest collections in the Museum. Leakey was passionate aboutopen human evolution and Africa, and was able to prove that the deep roots of human ancestry lay in his native east Africa. At Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania he excavated an extraordinary sequence of Pleistocene human evolution, discovering several hominin species and naming the earliest known human culture: the Oldowan. At Olorgesailie, Kenya, he excavated an Acheulean site that is still influential in our understanding of Lower Pleistocene human behaviour. On Rusinga Island in Lake Victoria, Kenya he found the Miocene ape ancestor Proconsul. He obtained funding to establish three of the most influential primatologists in their field, dubbed Leakey’s ‘ape women’; Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey and Birute Galdikas, who pioneered the study of chimpanzee, gorilla and orangutan behaviour respectively. His second wife Mary Leakey, whom he first hired as an artefact illustrator, went on to be a great researcher in her own right, surpassing Louis’ work with her own excavations at Olduvai Gorge. Mary and Louis’ son Richard followed his parents’ career path initially, discovering many of the most important hominin fossils including KNM WT 15000 (the Nariokotome boy, a near complete Homo ergaster skeleton), KNM WT 17000 (the type specimen for Paranthropus aethiopicus), and KNM ER 1470 (the type specimen for Homo rudolfensis with an extremely well preserved Archaeopressendocranium). -

M74* Vol.WV—No. 75 Nad1p111„:. 3Rd December, 1993

Vol.WV—No. 75 NAD1p111„:. 3rd December, 1993 Peke SI 20 GAZETTE NOTICES Gamin Norton—(card.) The , Land Disputes Tribunals Act—Appointments 1814-l816 The Nstional Assembly and Presidential ElectioaS Act-t-Withdrawal 1859 The Oaths and Statutory Declarations Act—'A cam- The Trust Land Act—Setting Apart of Land The Local Government Act—Appointments ... ... 1817 The Registration of Titles Act—Issue of Provisions) SUPPLEMENT No. 77 Ontilicees, etc. ••• 101744,18 Acts, 1993 The Registered Land Act—Registration of bent- ...ISIS-1820 PAO menu, etc. The Insurance (Amendment) Act, 1993 453 The Transport Licensing Act—Approvals, etc. ...'182f=1823 456 The /Menai Loans Act—Loss of Treasury Bills, ltd. 1823 The APpropriation Act, 1993 ... The EXport Processing Zones (Amendment) AU Administration 1SM-1813 Probate. 1993, Ogenies Act—First Meeting of Creditors and Con ... 1853-1815 Thes Seeelies Rules—Registrations ••• SUPPLEMENT No. 78 The Tiede Unions Act—Registrations, etc. • • , Lakin Supplement 1858-1857 Local Government Notices Lean. Nona No. M74* Change ot Names 363 The Customs and Facile (Unassembled Vehicles) Regulations, 1993 ... Closure of Roads 364—The Stamp Duty Act—Exemption ... Public Notice •.. 1814 THE KENYA GAZETTE 3rd December, 1993 GAZETTE Mattes No. 6341 SCHEDULE—(Contd.) THE LAND DISPUTES TRIBUNALS ACT Names District (No. 18 of 1990) Peter Buoga Mada“ Siaya. APPOINITAENT OP ELDERS Peter °loch Muranga Siaya. IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred by section 5 of the , Walter Muganda Siaya. Land Disputes Tribunak Act, the Minister for Lands and Agrrey Olweny Slays. Settlement, appoints the persons named in the fist column of Oloch Kabis Siaya. the schedule to be elders to hear land matters within the Tom Wanyande Siaya. -

Responsibility for Disease Management on Rusinga Island

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2009 Responsibility for Disease Management on Rusinga Island: Reconciling the Limitations of External Aid and the Role of Community-Based Initiatives Allyson Russell SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Community Health and Preventive Medicine Commons, and the Public Health Education and Promotion Commons Recommended Citation Russell, Allyson, "Responsibility for Disease Management on Rusinga Island: Reconciling the Limitations of External Aid and the Role of Community-Based Initiatives" (2009). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 905. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/905 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Disease Management on Rusinga Island Russell 1 Responsibility for Disease Management on Rusinga Island: Reconciling the Limitations of External Aid and the Role of Community-Based Initiatives Allyson Russell School for International Training Kenya: Development, Health and Society Fall 2009 Academic Directors: Odoch Pido & Jamal Omar Adviser : Dr. Mohamed Karama, Ph.D. Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Disease Management on Rusinga Island Russell 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Firstly, I must thank the Rusinga Island community for a warmer welcome than I ever could have asked for. I especially want to thank Mama Benter and the rest of my Rusinga Island family: Blasto, Samuel, Ibrahim, Teddy, Joan, Faith, Whitney and Peter, for inviting me into their home and taking such good care of me. -

Age at First Molar Emergence in Early Miocene Afropithecus Turkanensis

Journal of Human Evolution 44 (2003) 307–329 Age at first molar emergence in early Miocene Afropithecus turkanensis and life-history evolution in the Hominoidea Jay Kelley1*, Tanya M. Smith2 1 Department of Oral Biology (m/c 690), College of Dentistry, University of Illinois at Chicago, 801 S. Paulina, Chicago, IL 60612, USA 2 Interdepartmental Doctoral Program in Anthropological Sciences, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794, USA Received 12 July 2002; accepted 7 January 2003 Abstract Among primates, age at first molar emergence is correlated with a variety of life history traits. Age at first molar emergence can therefore be used to broadly infer the life histories of fossil primate species. One method of determining age at first molar emergence is to determine the age at death of fossil individuals that were in the process of erupting their first molars. This was done for an infant partial mandible of Afropithecus turkanensis (KNM-MO 26) from the w17.5 Ma site of Moruorot in Kenya. A range of estimates of age at death was calculated for this individual using the permanent lateral incisor germ preserved in its crypt, by combining the number and periodicity of lateral enamel perikymata with estimates of the duration of cuspal enamel formation and the duration of the postnatal delay in the inception of crown mineralization. Perikymata periodicity was determined using daily cross striations between adjacent Retzius lines in thin sections of two A. turkanensis molars from the nearby site of Kalodirr. Based on the position of the KNM-MO 26 M1 in relation to the mandibular alveolar margin, it had not yet undergone gingival emergence. -

Short.Pdf (8.887Kb)

3D ANALYSIS OF HIP JOINT MOBILITY AND THE EVOLUTION OF LOCOMOTOR ABILITIES IN MIOCENE HOMINOIDS Ashley S. Hammond Dr. Carol V. Ward, Dissertation Supervisor ABSTRACT The emergence of extant ape-like locomotor behaviors has become a defining issue in reconstructing ape evolution. Suspensory positional behaviors, such as antipronograde bridging, climbing, clambering and transfer, distinguish extant hominoids from Old World monkeys and most New World monkeys. It has been widely theorized that suspensory behaviors involve highly abducted hip joint postures, potentially permitting suspensory behaviors to be inferred from joint function rather than relying on isolated morphologies. This thesis tests whether adaptations for suspensory behaviors can be inferred in fossil nonhuman hominoids from the hip joint. The first study tests the association between suspensory behaviors and hip mobility in anesthetized living anthropoids (n=104). Suspensory taxa were found to have significantly higher passive ranges of abduction and external rotation compared to non-suspensory taxa. The second study developed a digital modeling technique to estimate range of hip abduction and then tested the accuracy of the modeling approach against the live animal data. Hip joint abduction and the abducted knee position were reconstructed in a large sample of extant anthropoids (n=252) and then quantitatively compared these simulations to the in vivo data for passive range of abduction. Suspensory taxa were significantly larger in both simulated abduction (degrees) and abducted knee position (mm), although there was overlap between locomotor groups. The results provided a hypothetical framework for how to interpret abduction modeled in fossil taxa. The final study modeled hip abduction in early Miocene hominoid Proconsul nyanzae, late Miocene crown hominoid Rudapithecus hungaricus, and several large- bodied Plio-Pleistocene fossil cercopithecoids (Paracolobus mutiwa, Paracolobus chemeroni, Theropithecus oswaldi) using the validated modeling approach from the second study. -

08 Early Primate Evolution

Paper No. : 14 Human Origin and Evolution Module : 08 Early Primate Evolution Development Team Principal Investigator Prof. Anup Kumar Kapoor Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi Dr. Satwanti Kapoor (Retd Professor) Paper Coordinator Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi Mr. Vijit Deepani & Prof. A.K. Kapoor Content Writer Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi Prof. R.K. Pathak Content Reviewer Department of Anthropology, Panjab University, Chandigarh 1 Early Primate Evolution Anthropology Description of Module Subject Name Anthropology Paper Name Human Origin and Evolution Module Name/Title Early Primate Evolution Module Id 08 Contents: Fossil Primates: Introduction Theories of primate origin Primates: Pre- Pleistocene Period a. Palaeocene epoch b. Eocene epoch c. Oligocene epoch d. Miocene – Pliocene epoch Summary Learning outcomes: The learner will be able to develop: an understanding about fossil primates and theories of primate origin. an insight about the extinct primate types of Pre-Pleistocene Period. 2 Early Primate Evolution Anthropology Fossil Primates: Introduction In modern time, the living primates are graded in four principle domains – Prosimian, Monkey, Ape and man. On the basis of examination of fossil evidences, it has been established that all the living primates have evolved and ‘adaptively radiated’ from a common ancestor. Fossil primates exhibit a palaeontological record of evolutionary processes that occurred over the last 65 to 80 million years. Crucial evidence of intermediate forms, that bridge the gap between extinct and extant taxa, is yielded by the macroevolutionary study of the primate fossil evidences. The paleoanthropologists often utilize the comparative anatomical method to develop insight about morphological adaptations in fossil primates. -

Livelihoods, Vulnerability and the Risk of Malaria on Rusinga Island/Kenya

Livelihoods, vulnerability and the risk of malaria on Rusinga Island/Kenya Magisterarbeit zur Erlangung der Würde des Magister Artium der Philologischen, Philosophischen und Wirtschafts- und Verhaltenswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg i. Br. Vorgelegt von Philipp Weckenbrock aus Bad Oldesloe WS 2004/05 Geographie Acknowledgements The realisation of this study would not have been possible without the help of many people. I would like to thank Prof. Dr. A. Drescher, HD Dr. C. Dittrich, Prof. Dr. R. Mäckel, Dr. G. Killeen and M. Quinlivan for their support during the preparatory phase of my fieldwork, which was partly sponsored by the Verband der Freunde der Universität Freiburg im Breisgau e.V. In Kenya, Dr. U. Fillinger offered a lot of help, not only concerning the design of the fieldwork but also in many other matters, for which I am very grateful. Also many thanks to the other people at the International Centre for Insect Physiology and Ecology (ICIPE), in particular Dr. R. Mukabana. In Nairobi and on Rusinga Island, I received much assistance from the side of the Christian Children’s Fund (CCF), especially from I. Kiche and E. Wamai. It was always a pleasure to work together with the malaria team in general and the malaria volunteers on Rusinga in particular. Also, I would like to express my gratitude to the many people in Kaknaga/Ufira zone on Rusinga Island who, with their warm hospitality, friendliness and patience, made working there a very rewarding experience. Thanks to C. Dietsche and M. Bodenhöfer and to Prof. Dr. T. Krings, the supervisor of this master’s thesis.