Sequencing with Style Marty Cutler May 1, 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jazz Collection: Lyle Mays

Jazz Collection: Lyle Mays Dienstag, 19. November 2013, 21.00 - 22.00 Uhr Samstag, 23. November 2013, 22.00 - 24.00 Uhr (Zweitsendung) Ohne ihn wäre der Gitarrist Pat Metheny nicht, was er heute ist: Lyle Mays ist seit den Anfängen der Pat Metheny Group mit dabei, ist Ko-Autor der allermeisten Stücke dieser weltberühmten Fusion-Band und nie richtig aus dem Schatten von Strahlemann Metheny herausgekommen. Wer je von der Pat Metheny Group gehört hat, der kennt Lyle Mays: der Pianist, Keyboarder und Komponist ist die rechte Hand von Pat Metheny. Er hat praktisch alle wichtigen Stücke dieser weltberühmten Band mit Metheny zusammen komponiert - und ist dennoch immer im Schatten von Metheny geblieben. Dabei beherrscht Lyle Mays das ganze Spektrum von elektronischen Soundteppichen bis zum makellosen akustischen Piano-Jazz perfekt. Wie ist Lyle Mays zu einem solchen musikalischen Tausendsassa geworden? Und warum wird er als Komponist ständig etwas unterschätzt? Immanuel Brockhaus ist Gast von Jodok Hess. Lab `75: Lab `75 LP NTSU LJ108 Track 2: Ouverture to the Royal Mongolian Suma Foosball Festival Pat Metheny: As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls CD ECM 1190 Track 2: Ozark Pat Metheny Group: Offramp CD ECM 1216 Track 6: James Lyle Mays Trio: Fictionary CD Geffen GED24521 Track 9: Falling Grace Lyle Mays: Solo (Improvisations For Expanded Piano) CD Warner Bros. 47284 Track 10: Long Life Pat Metheny Group: Speaking Of Now CD Warner Bros 48025 Track 2: Proof Bonustracks – nur in der Samstagsausgabe Pat Metheny Group: Pat Metheny Group CD ECM Track 6: Lone Jack Track 1: San Lorenzo Pat Metheny Group: American Garage CD ECM Track 6: Cross the Heartland Track 4: American Garage Lyle Mays: Street Dreams CD Geffen Records Track 3: Chorinho Track 4: Possible Straight Joni Mitchel: Shadows and Light CD Elektra Track 5: Good Bye Poork-Pie Hat Track 9: Hejira Lyle Mays: Solo (Improvisations For Expanded Piano) CD Warner Bros. -

MUSIC PRODUCTION GUIDE Official News Guide from Yamaha & Easy Sounds for Yamaha Music Production Instruments

MUSIC PRODUCTION GUIDE OFFICIAL NEWS GUIDE FROM YAMAHA & EASY SOUNDS FOR YAMAHA MUSIC PRODUCTION INSTRUMENTS 04|2014 SPECIAL EDITION Contents 40th Anniversary Yamaha Synthesizers 3 40 years Yamaha Synthesizers The history 4 40 years Yamaha Synthesizers Timeline 5 40th Anniversary Special Edition MOTIF XF White 23 40th Anniversary Box MOTIF XF 28 40th Anniversary discount coupons 30 40th Anniversary MX promotion plan 31 40TH 40th Anniversary app sales plan 32 ANNIVERSARY Sounds & Goodies 36 YAMAHA Imprint 41 SYNTHESIZERS 40 YEARS OF INSPIRATION YAMAHA CELEBRATES 40 YEARS IN SYNTHESIZER-DESIGN WITH BRANDNEW MOTIF XF IN A STUNNIG WHITE FINISH SARY PRE ER M V IU I M N N B A O X H T 0 4 G N I D U L C N I • FL1024M FLASH MEMORY Since 1974 Yamaha has set new benchmarks in the design of excellent synthesizers and has developed • USB FLASH MEMORY (4GB) innovative tools of creativity. The unique sounds of the legendary SY1, VL1 and DX7 have influenced a INCL. SOUND LIBRARIES: whole variety of musical styles. Yamaha‘s know-how, inspiring technique and the distinctive sounds of a - CHICK’S MARK V - CS-80 40-years-experience are featured in the new MOTIF XF series that is now available in a very stylish - ULTIMATE PIANO COLLECTION white finish. - VINTAGE SYNTHESIZER COLLECTION YAMAHASYNTHSEU YAMAHA.SYNTHESIZERS.EU YAMAHASYNTHESIZEREU EUROPE.YAMAHA.COM MUSIC PRODUCTION GUIDE 04|2014 40TH ANNIVERSARY YAMAHA SYNTHESIZERS In 1974 Yamaha produced its first portable Yamaha synthesizers and workstations were and still are analog synthesizer with the SY-1. The the first choice for professionals and amateurs in the multi- faceted music business. -

MOTIF XF Owner's Manual

MUSIC PRODUCTION SYNTHESIZER Owner’s Manual EN SPECIAL MESSAGE SECTION PRODUCT SAFETY MARKINGS: Yamaha electronic ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES: Yamaha strives to produce products may have either labels similar to the graphics products that are both user safe and environmentally shown below or molded/stamped facsimiles of these graph- friendly. We sincerely believe that our products and the pro- ics on the enclosure. The explanation of these graphics duction methods used to produce them, meet these goals. In appears on this page. Please observe all cautions indicated keeping with both the letter and the spirit of the law, we on this page and those indicated in the safety instruction sec- want you to be aware of the following: tion. Battery Notice: This product MAY contain a small non- rechargeable battery which (if applicable) is soldered in place. The average life span of this type of battery is approx- CAUTION imately five years. When replacement becomes necessary, RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK contact a qualified service representative to perform the DO NOT OPEN replacement. Warning: Do not attempt to recharge, disassemble, or CAUTION: TO REDUCE THE RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK. DO NOT REMOVE COVER (OR BACK). incinerate this type of battery. Keep all batteries away from NO USER-SERVICEABLE PARTS INSIDE. children. Dispose of used batteries promptly and as regu- REFER SERVICING TO QUALIFIED SERVICE PERSONNEL. lated by applicable laws. Note: In some areas, the servicer is required by law to return the defective parts. However, you do have the option of having the servicer dispose of these parts for you. The exclamation point within the equi- Disposal Notice: Should this product become damaged lateral triangle is intended to alert the beyond repair, or for some reason its useful life is consid- user to the presence of important operat- ered to be at an end, please observe all local, state, and fed- ing and maintenance (servicing) instruc- eral regulations that relate to the disposal of products that tions in the literature accompanying the contain lead, batteries, plastics, etc. -

Dana Podcast Transcript

Transcript of Dana Podcast—Pat Metheny’s Brain on Music Guest: Pat Metheny was born in Kansas City on August 12, 1954 into a musical family. Starting on trumpet at the age of 8, Metheny switched to guitar at age 12. By the age of 15, he was working regularly with the best jazz musicians in Kansas City, receiving valuable on-the-bandstand experience at an unusually young age. Mr. Metheny first burst onto the international jazz scene in 1974. With the release of his first album, Bright Size Life (1975), he reinvented the traditional "jazz guitar" sound for a new generation of players. Throughout his career, Mr. Metheny has continued to re-define the genre by utilizing new technology and constantly working to evolve the improvisational and sonic potential of his instrument. As well as being an accomplished musician, Mr. Metheny has also participated in the academic arena as a music educator. At 18, he was the youngest teacher ever at the University of Miami. At 19, he became the youngest teacher ever at the Berklee College of Music, where he also received an honorary doctorate more than twenty years later (1996). Over the years, Mr. Metheny has won countless polls as "Best Jazz Guitarist" and awards, including three gold records for Still Life (Talking), Letter from Home, and Secret Story. He has also won 20 Grammy Awards in 12 different categories. Host: Bill Glovin serves as executive editor of The Dana Foundation. Prior to joining Dana Mr. Glovin was senior editor of Rutgers Magazine and editor of Rutgers Focus. -

Music Production Guide

MUSIC PRODUCTION GUIDE OFFICIAL NEWS GUIDE FROM YAMAHA & EASY SOUNDS FOR YAMAHA MUSIC PRODUCTION INSTRUMENTS 01|2016 Contents MONTAGE Music In Motion 2 reface YC 19 DTX-News from NAMM 2016 24 Sounds & Goodies 27 MUSIC IN MOTION Imprint 44 MUSIC PRODUCTION GUIDE 01|2016 MUSIC IN MOTION The time has come. Yamaha's new The name MONTAGE represents a completely new synthesizer flagship is here: MONTAGE. generation of Yamaha Music Synthesizers, that we want to bring you closer with this document. Welcome to the new era in synthesizers from the company that brought you the It starts with a list of features that is made up of official industry-changing DX and the hugely marketing texts and our supplements. popular MOTIF. This is followed by detailed chapters about the major new Building on the legacy of these two iconic features of MONTAGE. keyboards, the Yamaha Montage sets the next milestone for synthesizers with SOPHISTICATED DYNAMIC sophisticated dynamic control, massive CONTROL sound creation and streamlined workflow Music is expression. MONTAGE adds a new level of all combined in a powerful keyboard expression with the Motion Control Synthesis Engine. designed to inspire your creativity. This engine allows a variety of methods to interact with If you liked the DX and MOTIF, get ready to and channel your creativity into finding your own unique love MONTAGE. sound. YAMAHA.COM 2 MUSIC PRODUCTION GUIDE 01|2016 MOTION CONTROL SYNTHESIS ENGINE The Motion Control Synthesis Engine unifies and controls two iconic Sound Engines: AWM2 (high-quality waveform and synthesis) and FM-X (modern, pure Frequency Modulation synthesis.) These two engines can be freely zoned or layered across eight Parts in a single MONTAGE Performance. -

Music Production Guide

MUSIC PRODUCTION GUIDE OFFICIAL NEWS GUIDE FROM YAMAHA & EASY SOUNDS FOR YAMAHA MUSIC PRODUCTION INSTRUMENTS 07|2019 MONTAGE OS V3.0 MODX OS V2.0 New Features & Effects 3 Yamaha 45 years of synthesizers 12 Yamaha DTX Drums & EAD10 It's your turn now! 28 YAMAHA – Goodies & Sounds 29 45 YEARS OF Imprint 46 SYNTHESIZERS MONTAGE OS V3.0 MODX OS V2.0 NEW FEATURES & EFFECTS OVERVIEW These are the new features and therefore the topics of this Guide: • New Effects: • „VCM Mini Filter“ • „VCM Mini Booster“ • „Wave Folder“ • High-Speed LFO • „Super Knob Link“ storable per Scene • „Keyboard Control“ storable per Scene • MIDI Mode „Hybrid“ (in addition to "Multi" and "Single") The OS Updates to Version 3.0 for MONTAGE • Links between Performances and Songs, Patterns, or and 2.0 for MODX are among the most Audio files via the Live Set comprehensive since the release of the • „Rhythm Patterns“ (MODX feature) for MONTAGE MONTAGE series. For this reason, we have • USB Host function for direct connection of class- decided to publish a Quick Guide in two compliant compatible instruments parts. This first part covers all new features • Global Micro-Tuning except the Pattern Sequencer, which will be discussed in part 2. • Audition Loop selectable (ON/OFF) • General improvements of the user interface However, the actual update process is not part of this Quick Guide. Please simply follow the instructions included with In addition, 52 new Performances have been added with the Update. the Update, but those are not discussed in this Guide. MONTAGE / MODX ESSENTIAL KNOWLEDGE 09|2019 VCM EFFECTS This Update includes two new VCM Effects (Virtual Component Modeling) in the Insert Effects and in System Effect Variation. -

MOTIF XF Owner's Manual

MUSIC PRODUCTION SYNTHESIZER Owner’s Manual EN SPECIAL MESSAGE SECTION PRODUCT SAFETY MARKINGS: Yamaha electronic ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES: Yamaha strives to produce products may have either labels similar to the graphics products that are both user safe and environmentally shown below or molded/stamped facsimiles of these graph- friendly. We sincerely believe that our products and the pro- ics on the enclosure. The explanation of these graphics duction methods used to produce them, meet these goals. In appears on this page. Please observe all cautions indicated keeping with both the letter and the spirit of the law, we on this page and those indicated in the safety instruction sec- want you to be aware of the following: tion. Battery Notice: This product MAY contain a small non- rechargeable battery which (if applicable) is soldered in place. The average life span of this type of battery is approx- CAUTION imately five years. When replacement becomes necessary, RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK contact a qualified service representative to perform the DO NOT OPEN replacement. Warning: Do not attempt to recharge, disassemble, or CAUTION: TO REDUCE THE RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK. DO NOT REMOVE COVER (OR BACK). incinerate this type of battery. Keep all batteries away from NO USER-SERVICEABLE PARTS INSIDE. children. Dispose of used batteries promptly and as regu- REFER SERVICING TO QUALIFIED SERVICE PERSONNEL. lated by applicable laws. Note: In some areas, the servicer is required by law to return the defective parts. However, you do have the option of having the servicer dispose of these parts for you. The exclamation point within the equi- Disposal Notice: Should this product become damaged lateral triangle is intended to alert the beyond repair, or for some reason its useful life is consid- user to the presence of important operat- ered to be at an end, please observe all local, state, and fed- ing and maintenance (servicing) instruc- eral regulations that relate to the disposal of products that tions in the literature accompanying the contain lead, batteries, plastics, etc. -

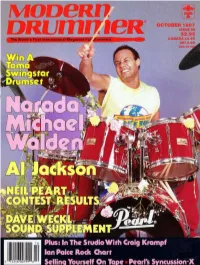

October 1987

Cover Photo by Ebet Roberts EDUCATION IN THE STUDIO Roberts An Introduction 42 Ebet by Craig Krampf by ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC Emphasizing Beats Photo by Rod Morgenstein 44 TEACHERS' FORUM Motivation by Ron Jordan 48 JAZZ DRUMMERS' WORKSHOP Basic Independence by Peter Erskine 72 ELECTRONIC INSIGHTS Marching To The MIDI Drummer by Bruce Nazarian 82 ROCK PERSPECTIVES Ringo Starr: The Early Period by Kenny Aronoff 102 ROCK CHARTS Ian Paice: "Perfect Strangers" by James Morton 106 CONCEPTS Listening NARADA MICHAEL by Roy Burns 120 CLUB SCENE WALDEN Selling Yourself On Tape In recent months, he has had great success as a producer for by Rick Van Horn 122 such artists as Whitney Houston and Aretha Franklin, but EQUIPMENT Narada Michael Walden isn't about to abandon his SHOP TALK drumming, and here he tells why. Snare Drum Options by Rick Mattingly 16 by John Clarke 76 PRODUCT CLOSE-UP More New Cymbals AL JACKSON by Rick Van Horn and Rick Until his untimely death, Al Jackson provided the backbeat Mattingly 126 for classic Memphis recordings by Booker T. & The MGs, Al ELECTRONIC REVIEW Greene, Sam & Dave, Otis Redding, and all the artists on Stax Pearl SC-40 Syncussion-X records. He is remembered by such friends and colleagues as by Bob Saydlowski, Jr. 128 Steve Cropper, Duck Dunn, Al Greene, and Jim Keltner. JUST DRUMS 132 by T. Bruce Wittet 22 REVIEWS PRINTED PAGE 104 PAUL LEIM PROFILES Since moving to L.A. from Dallas, Paul Leim has recorded PORTRAITS with an impressive array of artists, including Lionel Richie, Sherman Ferguson: Fire, Groove, Peter Cetera, and Kenny Rogers. -

How Steve Reich's Music Has Influenced Pat Metheny's and Lyle Mays' the Way Up

The Art of Composing: How Steve Reich's music has influenced Pat Metheny's and Lyle Mays' The Way Up A research into the history of composition techniques By Benjamin van Bruggen August 2014 1 \\\\\\\\\Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Emile Wennekes Dr. Eric Jas Contents Table of Illustrations 3 Table of Tables 4 \\\\\\\\\ABSTRACT 5 \\\\\\\\\INTRODUCTION 7 \\\\\\\\\PREFACE 13 CHAPTER A) PULSING REPEATED NOTES 21 Electric Counterpoint and Reich's compositional practice 21 As characteristic of The Way Up 24 CHAPTER B) THE PHASE SHIFTING TECHNIQUE 31 CHAPTER C) HARMONIC LANGUAGE 39 2 Piano and trumpet solo 40 The harmonic aspects of The Way Up’s main theme 42 CONCLUSION 53 \\\\\\\\\BIBLIOGRAPHY 56 \\\\\\\\\APPENDIX 1 58 Table of Illustrations Figure 1: The Way Up's lead-sheet's cover (Forsyth n.d.). 6 Figure 2: The Way Up's CD release has six different cover designs (AIGA Design Archives n.d.). 8 Figure 3: The Way Up's CD release's booklet (AIGA Design Archives n.d.). 11 Figure 4: Excerpt from Electric Counterpoint's score: bars 63-67 (silent parts not incorporated) (Reich 1987). 20 Figure 5: Pulsing repeated notes in The Way Up's opening measures (Metheny n.d.) 22 Figure 6: Pulsing repeated notes in The Way Up's opening measures (Metheny n.d.) 23 Figure 7: Pulsing repeated notes in The Way Up's opening measures (Metheny n.d.) 24 Figure 8: A scalar arpeggiating figure in the piano is added to the pulsing repeated notes played by the guitar (Metheny n.d.). 26 Figure 9: Reduction of harmonies and pulsing repeated notes in measures 1445-1516 (Metheny n.d.). -

Page 1 N E W R E L E a S E

NEW RELEASE O N I N T U I T I O N R E C O R D S R E C E I V E D 4 G R A M M Y N O M I N A T I O N S OREGON’s latest project, Oregon In Moscow, is a double CD with the Moscow Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra, and the group’s recorded debut of their orchestral repertoire—a prodigious body of work that has been developing over the life of the band, but never documented. In the thirty-year history of OREGON, there has always existed a strong kinship to orchestral music. The use of the double reeds alone has given the quartet an identity and expansive sound associated with the symphonic orchestra. This association isn’t confined only to their use of many orchestral instruments, but applies also to the composition and presentation of the music, including the careful attention to details such as articulation, dynamics, phrasing and tone production derived from their respective classical studies. Chief composer Ralph Towner explains, “OREGON came together as a group in New York City in 1970, and from the outset it was clear that our unusual instrumentation and collective musical experience invited a different approach to composition and improvisation. The jazz tradition of improvisation usually consists of the soloists taking turns improvising on the song’s harmonic structure, recycling the chord progressions and returning to the original melody only on the last repeat of the cycle. While still using and honoring this tradition, we began composing longer, more sectional forms that allowed each soloist to improvise on different material within the context of a single piece. -

Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Pat Metheny Group The Falcon And The Snowman (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Jazz / Stage & Screen Album: The Falcon And The Snowman (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) Country: Europe Style: Soundtrack MP3 version RAR size: 1613 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1552 mb WMA version RAR size: 1115 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 223 Other Formats: DMF RA AHX TTA ASF MIDI VOC Tracklist Hide Credits Psalm 121 / Flight Of The Falcon 1 –Pat Metheny Group 4:08 Written-By – L. Mays*, P. Metheny* Daulton Lee 2 –Pat Metheny Group 5:56 Written-By – L. Mays*, P. Metheny* Chris 3 –Pat Metheny Group 3:16 Written-By – L. Mays*, P. Metheny* "The Falcon" 4 –Pat Metheny Group 4:59 Written-By – L. Mays*, P. Metheny* This Is Not America 5 –David Bowie / Pat Metheny Group 3:53 Written-By – D. Bowie*, L. Mays*, P. Metheny* Extent Of The Lie 6 –Pat Metheny Group 4:15 Written-By – Lyle Mays, P. Metheny* The Level Of Deception 7 –Pat Metheny Group 5:45 Written-By – L. Mays*, P. Metheny* Capture 8 –Pat Metheny Group 3:57 Written-By – L. Mays*, P. Metheny* Epilogue (Psalm 121) 9 –Pat Metheny Group 2:14 Written-By – L. Mays*, P. Metheny* Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – EMI-Manhattan Records Phonographic Copyright (p) – EMI-Manhattan Records Phonographic Copyright (p) – David Bowie Licensed To – EMI America Records Marketed By – EMI Distributed By – EMI Made By – EMI Uden Credits Acoustic Bass, Electric Bass – Steve Rodby Co-producer – Lyle Mays Drums, Percussion – Paul Wertico Guitar Synthesizer, Acoustic Guitar, Electric Guitar – Pat Metheny Mixed By – Bob Clearmountain Producer – David Bowie, Pat Metheny Producer [Album Producer By] – Pat Metheny Synthesizer [Synthesizers], Piano – Lyle Mays Vocals – Pedro Aznar (tracks: 2, 4) Notes © ℗ 1985 EMI-Manhattan Records, a division of Capitol Records, Inc. -

Integrated Sampling Sequencer Real-Time External Control

For details please contact: Integrated Sampling Sequencer Real-time External Control Surface Modular Synthesis Plug-in System ISO9001 Ce document est imprimé sur du papier JQA-1868 sans chlore (ECF) avec de l’encre de soja. www.yamahasynth.com LCK0102 Printed in Japan Audio Phrases, MIDI Patterns, Sample Loops… MOTIF Puts All the Pieces Together! Musical inspiration can come from just about anywhere—a simple guitar riff, an arpeggiated synth sequence, a sampled vocal phrase… Such musical ideas, known as motifs, are the building blocks of all musical creation. Yamaha’s MOTIF Music Production Synthesizer gives you the power to put your motifs together and freely arrange them in ways never before imagined. The concept behind MOTIF is simple: Make the music creation process as easy and intuitive as possible, from conception to final creation. MOTIF achieves this by providing you with a vast palette of onboard sounds, extensive real-time control, and an integrated approach to sequencing that allows you to seamlessly record, edit, arrange and process both MIDI data and audio samples using a unified set of editing tools and functions. Thanks to this streamlined approach to music making, getting your motifs into the keyboard and putting the pieces together is easier than ever. It doesn’t matter where you start. With MOTIF, you can freely record MIDI and audio phrases into the sequencer and combine and arrange them any way you’d like–tweaking the groove, changing the tempo, and adding effects all along the way. And where you end…well, that’s entirely up to you! MOTIF — it’s the shortest distance between inspiration and creation.