The Computer Is Not a Tool to Help Us Do Whatever We Do, It Is What We Do, It Is the Medium on Which We Work1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Art in Enterprise

Report from the EU H2020 Research and Innovation Project Artsformation: Mobilising the Arts for an Inclusive Digital Transformation The Role of Art in Enterprise Tom O’Dea, Ana Alacovska, and Christian Fieseler This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 870726. Report of the EU H2020 Research Project Artsformation: Mobilising the Arts for an Inclusive Digital Transformation State-of-the-art literature review on the role of Art in enterprise Tom O’Dea1, Ana Alacovska2, and Christian Fieseler3 1 Trinity College, Dublin 2 Copenhagen Business School 3 BI Norwegian Business School This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 870726 Suggested citation: O’Dea, T., Alacovska, A., and Fieseler, C. (2020). The Role of Art in Enterprise. Artsformation Report Series, available at: (SSRN) https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3716274 About Artsformation: Artsformation is a Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation project that explores the intersection between arts, society and technology Arts- formation aims to understand, analyse, and promote the ways in which the arts can reinforce the social, cultural, economic, and political benefits of the digital transformation. Artsformation strives to support and be part of the process of making our communities resilient and adaptive in the 4th Industrial Revolution through research, innovation and applied artistic practice. To this end, the project organizes arts exhibitions, host artist assemblies, creates new artistic methods to impact the digital transformation positively and reviews the scholarly and practi- cal state of the arts. -

List of Different Digital Practices 3

Categories of Digital Poetics Practices (from the Electronic Literature Collection) http://collection.eliterature.org/1/ (Electronic Literature Collection, Vol 1) http://collection.eliterature.org/2/ (Electronic Literature Collection, Vol 2) Ambient: Work that plays by itself, meant to evoke or engage intermittent attention, as a painting or scrolling feed would; in John Cayley’s words, “a dynamic linguistic wall- hanging.” Such work does not require or particularly invite a focused reading session. Kinetic (Animated): Kinetic work is composed with moving images and/or text but is rarely an actual animated cartoon. Transclusion, Mash-Up, or Appropriation: When the supply text for a piece is not composed by the authors, but rather collected or mined from online or print sources, it is appropriated. The result of appropriation may be a “mashup,” a website or other piece of digital media that uses content from more than one source in a new configuration. Audio: Any work with an audio component, including speech, music, or sound effects. CAVE: An immersive, shared virtual reality environment created using goggles and several pairs of projectors, each pair pointing to the wall of a small room. Chatterbot/Conversational Character: A chatterbot is a computer program designed to simulate a conversation with one or more human users, usually in text. Chatterbots sometimes seem to offer intelligent responses by matching keywords in input, using statistical methods, or building models of conversation topic and emotional state. Early systems such as Eliza and Parry demonstrated that simple programs could be effective in many ways. Chatterbots may also be referred to as talk bots, chat bots, simply “bots,” or chatterboxes. -

<I>Victory Garden</I>

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 8-2012 Reading Ineffability and Realizing Tragedy in Stuart Moulthrop's Victory Garden Michael E. Gray Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gray, Michael E., "Reading Ineffability and Realizing Tragedy in Stuart Moulthrop's Victory Garden" (2012). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1188. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1188 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. READING INEFFABILITY AND REALIZING TRAGEDY IN STUART MOULTHROP’S VICTORY GARDEN A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Michael E. Gray August 2012 I would like to thank my wife, Lisa Oliver-Gray, for her steadfast support during this project. Without her love and the encouragement of my family and friends, I could not have finished. I would also like to thank my committee for their timely assistance this summer. Last, I would like to dedicate this labor to my father, Dr. Elmer Gray, who quietly models academic excellence and was excited to read a sprawling first draft. CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………..1-30 Chapter One…………………………………………………………………………31-57 Chapter Two…………………………………………………………………………58-86 Chapter Three………………………………………………………………………87-112 Appendix: List of Screenshots...………………………………………………….113-121 Notes………………………………………………………………………………122-145 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………….146-149 iv TABLE OF FIGURES Figure 1. -

Media Ecologies: Materialist Energies in Art and Technoculture, Matthew Fuller, 2005 Media Ecologies

M796883front.qxd 8/1/05 11:15 AM Page 1 Media Ecologies Media Ecologies Materialist Energies in Art and Technoculture Matthew Fuller In Media Ecologies, Matthew Fuller asks what happens when media systems interact. Complex objects such as media systems—understood here as processes, or ele- ments in a composition as much as “things”—have become informational as much as physical, but without losing any of their fundamental materiality. Fuller looks at this multi- plicitous materiality—how it can be sensed, made use of, and how it makes other possibilities tangible. He investi- gates the ways the different qualities in media systems can be said to mix and interrelate, and, as he writes, “to produce patterns, dangers, and potentials.” Fuller draws on texts by Félix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze, as well as writings by Friedrich Nietzsche, Marshall McLuhan, Donna Haraway, Friedrich Kittler, and others, to define and extend the idea of “media ecology.” Arguing that the only way to find out about what happens new media/technology when media systems interact is to carry out such interac- tions, Fuller traces a series of media ecologies—“taking every path in a labyrinth simultaneously,” as he describes one chapter. He looks at contemporary London-based pirate radio and its interweaving of high- and low-tech “Media Ecologies offers an exciting first map of the mutational body of media systems; the “medial will to power” illustrated by analog and digital media technologies. Fuller rethinks the generation and “the camera that ate itself”; how, as seen in a range of interaction of media by connecting the ethical and aesthetic dimensions compelling interpretations of new media works, the capac- of perception.” ities and behaviors of media objects are affected when —Luciana Parisi, Leader, MA Program in Cybernetic Culture, University of they are in “abnormal” relationships with other objects; East London and each step in a sequence of Web pages, Cctv—world wide watch, that encourages viewers to report crimes seen Media Ecologies via webcams. -

Brief CV (Pdf)

Antoinette LaFarge CV Professor of Digital Media, Department of Art, Claire Trevor School of the Arts, UC Irvine 92697, U.S.A. email: [email protected] url: http://www.antoinettelafarge.com/ Research Interests My beat is virtuality and its discontents. Areas of special inquiry include impersonation and improvisation, mixed realities, constructed narrative, technology-mediated performance, online role-play and avatarism, fictive art, and design for communication. I work with both traditional and digital media, although nearly all my projects are heavily computer-mediated and usually require custom programming. Many recent projects have involved telematic performance and virtual role-playing environments. Teaching Positions University of California, Irvine (1999-present) Professor of Digital Media, Dept. of Art (2010-present) Associate Dean for Graduate Affairs, Claire Trevor School of the Arts (2009-2013, 2014-15) Associate Professor of Digital Media, Dept. of Studio Art (2003-10) Assistant Professor of Digital Media, Dept. of Studio Art (1999-2003) Program faculty, Arts Computation Engineering (ACE) Program (2003-2010) Affiliated faculty, Center in Law, Society, and Culture (2008-present) Associate Director, Game Culture & Technology Laboratory (2003-2012) Director of Academic Computing, Claire Trevor School of the Arts (2004-2012) School of Visual Arts, New York (1995-99) Adjunct faculty, M.F.A. program in Computer Art. Adjunct faculty, M.F.A. program in Photography & Related Media. Lecturer, Internet courses and workshops in the Continuing Education program. Publications * = peer reviewed ** = book ** Monkey Encyclopedia W. ICI Press, 2019. * "Alive in the Now: Ekphrasis in Philip K. Dick and William Gibson." MOSF Journal of Science Fiction 2:1 (September 2017). -

Interactive Digital Narrative History, Theory and Practice

Interactive Digital Narrative History, Theory and Practice Edited by Hartmut Koenitz, Gabriele Ferri, Mads Haahr, Diğdem Sezen and Tonguç İbrahim Sezen First published 2015 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 and by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2015 Taylor & Francis The right of the editor to be identified as the author of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data [CIP data] ISBN: 978-1-138-78239-6 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-315-76918-9 (ebk) Typeset in Sabon by codeMantra Contents Foreword ix NICK MONTFOrt Acknowledgments xv 1 Introduction: Perspectives on Interactive Digital Narrative 1 Hartmut KOENITZ, GABRIELE FERRI, MADS HAAHR, DIğDEM SEZEN AND TONGUÇ İBRAHIM SEZEN SECTION I: IDN HISTORY Introduction: A Concise History of Interactive Digital Narrative 9 -

Benchmark Fiction: a Framework for Comparative New Media Studies

Benchmark Fiction: A Framework for Comparative New Media Studies Christy Dena Jeremy Douglass Mark Marino University of Melbourne UC Santa Barbara UC Riverside School of Creative Arts 2607 South Hall, UCSB 8325 Fordham Rd. Parkville, Australia Santa Barbara, CA 93106-3170 USA LA, CA 90045 USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract The underlying tenet of producing benchfic – the separation of How do we compare eliterature forms? What does it mean for a ‘form’ from ‘content’ – is highly problematic. It is difficult or work to be implemented as hypertext, interactive fiction, or impossible to pinpoint where form ends and content begins in a chatbot? "Benchmark fiction" is a methodology for creating given work, particularly artistic work designed to be experienced 'benchmarks' - sets of adaptations of the “same” eliterature content as a unified whole. Yet, with benchfic as with other processes of across different media for the purpose of comparative study. adaptation, translation and remediation, the problem of While total equivalence between the resulting 'benchfic' is determining which elements to hold constant and which to vary is impossible, praxis remains important: by creating 'equivalent' in large part the value of the undertaking. media and then critiquing them, we reveal our own definitions of In the process of producing benchfic, one’s concept of ‘form’ is media through process. Work on the first story to be formalized as one’s vision of the content takes new shape. These benchmarked, “The Lady or the Tiger” (1882) by Frank R. very formalizations may break under the weight of the creative Stockton, inspired a framework for displaying sources through experiments, testing their limitations, another goal of the Project. -

NS /DE: Network Radio Business

ISSUE NUMBER 955 THE INDUSTRY'S NEWSPAPER AUGUST 21, 1992 Tough Times Continue In /NS /DE: Network Radio Business NEW LOOK FOR ABC, Westwood One involved in latest wave NEW ROCK of layoffs; ABC cancels evening talk shows Beginning with this issue, R &R Last week, two major radio In a memo to his staff, ABC heralds New Rock's continued networks relayed signals that Radio Networks President Bob growth by significantly their economic woes are contin- Callahan said the reductions uing, with little hope of immedi- were the culmination of a three - expanding the music and ate recovery. ABC Radio Net- month effort to consolidate its editorial coverage of this exciting works laid off a reported 51 em- operations with those of its Sa- format: ployees last Friday (8/14), tellite Music Network sub- while Westwood One pink -slip- sidiary. Chart now includes four -week ped 15 fulltimers from the NBC/ "These decisions involve the trending, emphasis tracks, and Mutual newsroom. relocation of some employees to Dallas, where SMN is based, individual rotations and the reduction cf some other New & Active and Significant staff whose job duties became Action lists debut Station Trading Blitz Begins duplicative in the melding of these operations," Callahan Shawn Alexander's column Karmazin uses new duopoly rules to pick up cash -flow stations in stated in the memo. appears weekly, featuring tips Cook Inlet $100 million An ABC staff member, who Chicago, Boston, and Atlanta from for asked not to be identified, said on programming, promotion, 100 positions were either elimin- Striking fast to take advant- properties. -

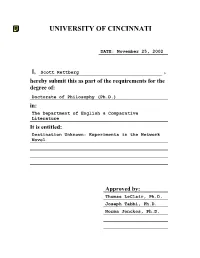

Destination Unknown: Experiments in the Network Novel

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: November 25, 2002 I, Scott Rettberg , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in: The Department of English & Comparative Literature It is entitled: Destination Unknown: Experiments in the Network Novel Approved by: Thomas LeClair, Ph.D. Joseph Tabbi, Ph.D. Norma Jenckes, Ph.D. Destination Unknown: Experiments in the Network Novel A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences 2003 by Scott Rettberg B.A. Coe College, 1992 M.A. Illinois State University, 1995 Committee Chair: Thomas LeClair, Ph.D. Abstract The dissertation contains two components: a critical component that examines recent experiments in writing literature specifically for the electronic media, and a creative component that includes selections from The Unknown, the hypertext novel I coauthored with William Gillespie and Dirk Stratton. In the critical component of the dissertation, I argue that the network must be understood as a writing and reading environment distinct from both print and from discrete computer applications. In the introduction, I situate recent network literature within the context of electronic literature produced prior to the launch of the World Wide Web, establish the current range of experiments in electronic literature, and explore some of the advantages and disadvantages of writing and publishing literature for the network. In the second chapter, I examine the development of the book as a technology, analyze “electronic book” distribution models, and establish the difference between the “electronic book” and “electronic literature.” In the third chapter, I interrogate the ideas of linking, nonlinearity, and referentiality. -

Does Lara Croft Wear Fake Polygons? Gender and Gender-Role Subversion in Computer Adventure Games a B S T R a C T

GENERAL NOTE Does Lara Croft Wear Fake Polygons? Gender and Gender-Role Subversion in Computer Adventure Games A B S T R A C T The subject matter of this ar- ticle emerged in part out of re- Anne-Marie Schleiner search for the author’s thesis project and first game patch, Ma- dame Polly, a “first-person shooter gender hack.” Since the time it was written, there has been an up- surge of interest and research in computer games among artists ost-industrial capitalist economies are develop- search involving the nascent and media theoreticians. Consider- P able shifts in gaming culture at ing into cultures of “play,” in which a pervasive “play ethic” is “third-person shooter/adventure large have taken place, most nota- superseding the work ethic [1]. According to economist Jer- game with female heroine” bly a shift toward on-line games, emy Rifkin, as large percentages of the human labor force are genre—exemplified by Eidos In- as well as an increase in the num- rendered superfluous by more efficient technologies, we will teractive and Core Design’s popu- ber of female players. The multi- need to reinvest value in other sorts of human activities that lar game Tomb Raider—has led directional information space of the network offers increasing pos- fall outside of the production paradigm [2]. Even within cor- me from gender analysis of film, sibilities for interventions and gen- porate environments, play is seeping into the workplace: for particularly of the horror film der reconfigurations such as those instance, “strung-out” programmers may blow off steam by genre, to science fiction, to vir- discussed at the end of the article. -

The Moment in Hypertext: a Brief Lexicon of Time

The Moment in Hypertext: A Brief Lexicon of Time Marjorie C. Luesebrink School of Humanities and Languages Irvine Valley College Irvine, CA 92620 Tel: l-7 14-644-6587 E-mail: luesebrl @ix.netcom.com ABSTRACT In both technical and critical settings, the theories which Hypertext literature has been characterized as spatial explore the spatial basis for hypertext have helped writers construct by many of the critics involved with its aesthetics understand and manipulate the medium. Frank Shipman and poetics. Michael Joyce, Cathy Marshall, Mark and Cathy Marshall, drawing on a considerable body of Bernstein, Carolyn Guyer, George Landow, Stuart research in traversal technology, and in their own Moulthrop and many others have explored the way in which demonstrations with space-placeholders, such as “VIKI: metaphors of visual space can inform hypertexts--impacting Spatial Hypertext”[l], have formalized these issues.121 both meaning and process. Although these writers refer to George Landow, in Hypertext 2.0 revisits the primacy of the time/space continuum, their writing has been less spatial visualization as both controlling metaphor and concerned with temporal constructs--how time might conceptual precondition of hypertext writing. He identifies influence the programming, writing, and reading of the first issue of linked writing as one of: “orientation hypertext literature. Time factors, however, could be information....necessary for finding one’s place. The viewed as important elements in the way hypertexts are second concerns navigation information....the third conceived and received. This paper seeks to raise questions concerns exit or departure information and the fourth about issues of time--and to suggest some possible arrival or entrance information {italics are the categories that might be investigated. -

Twine and the Challenge to Reading

Twine and the Challenge to Reading Stuart Moulthrop University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee June, 2020 This paper is adapted from the final chapter of Twining, a book about the Twine text- gaming platform forthcoming from Amherst College Press. The book version adds a final, personal perspective omitted here for reasons of length. Twining also offers a history of the software, critical discussions of several influential Twine works, practical chapters exploring creative possibilities of the platform, and reflections and interviews of Twine developers. 1. If you can read this… In 2017 John Cayley, a field leader in digital literary arts, called for a change of direction. In a landmark article called “Aurature at the End(s) of Electronic Literature,” he proposes a turn from visible text to sound: the aural delivery of words spoken or synthesized, using emerging home entertainment platforms, so-called smart speakers like Amazon’s Echo (Cayley "Aurature"). Paradigm shifts are inevitably rivalrous. When you are trying to open a new path, it’s necessary to show the errors of other ways. Accordingly, Cayley deprecates several electronic writing practices, including some with roots in his own academic program. When he comes to the Twine writing platform, he is more skeptical than dismissive, though he raises important questions: In the case of expressive hypertext — with choose-your-own-adventure gaming capabilities — we can now point to Twine as a platform still gaining significant popularity. But will it ever end up supporting Twine-writers and designers commercially, or as prominent literary practitioners? (Cayley "Aurature" n.p.) Cayley allows that Twine is popular and becoming more so.