Haida Marine Traditional Knowledge Study Report Volume 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

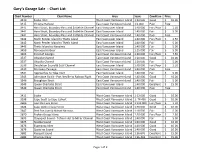

Gary's Charts

Gary’s Garage Sale - Chart List Chart Number Chart Name Area Scale Condition Price 3410 Sooke Inlet West Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Good $ 10.00 3415 Victoria Harbour East Coast Vancouver Island 1:6 000 Poor Free 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3441 Haro Strait, Boundary Pass and Sattelite Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Poor Free 3442 North Pender Island to Thetis Island East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3442 North Pender Island to Thetis Island East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3443 Thetis Island to Nanaimo East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3459 Nanoose Harbour East Vancouver Island 1:15 000 Fair $ 5.00 3463 Strait of Georgia East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 7.50 3537 Okisollo Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Good $ 10.00 3537 Okisollo Channel East Coast Vancouver Island 1:20 000 Fair $ 5.00 3538 Desolation Sound & Sutil Channel East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair/Poor $ 2.50 3539 Discovery Passage East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Poor Free 3541 Approaches to Toba Inlet East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3545 Johnstone Strait - Port Neville to Robson Bight East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Good $ 10.00 3546 Broughton Strait East Coast Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Fair $ 5.00 3549 Queen Charlotte Strait East Vancouver Island 1:40 000 Excellent $ 15.00 3549 Queen Charlotte Strait East -

Oregon Country Fair Board of Directors' Meeting February 1, 2016, 7:00, NW Youth Corps, Columbia Room

Oregon Country Fair Board of Directors' Meeting February 1, 2016, 7:00, NW Youth Corps, Columbia room Board members present: Diane Albino, Casey Marks Fife, Justin Honea, Lucy Kingsley, Jack Makarchek (president), Indigo Ronlov (vice-president), Kirk Shultz, Jon Silvermoon , Lawrence Taylor (Alternate), Sue Theolass, Bear Wilner-Nugent. Peach Gallery present: Staff (Tom, Crystalyn, Robin and Shane), Officers (Hilary, Grumpy and Randy), and 41 members and guests. Indigo: I would like move the reports for committee and staff after the Old business due to the amount of business that we have to cover tonight. Everyone agreed. New Business Approve Capital Projects (Bear) Approve Caretaker job description (Jon) Appoint Caretaker hiring committee (Jon) Appoint Pablo Bristow to the Vision Action committee Appoint Carmella Fleming to the Diversity Task Force Appoint Paxton to the Community Center Committee (Kirk) Policy for naming New Area (Kirk) Appoint Becky Lamarsh as Site crew coordinator (Bear) Announcements Peggy: KOCF fundraiser is March 5, 2016 at Domaine Meriwether winery from 6:00pm to 8:30pm. It will be a silent auction and we are accepting donations. Etouffee will be the band. Gary: My wife Monica and I bought the Noti High School. We will keep it a school and open it up for camping during this year’s Fair. Sue: Sunday, February 7, 2016 is the second annual Kareng fund art bingo at the Broadway Commerce Center at 44 W Broadway. There will be select goodies from Dana’s cheesecake with all of those proceeds going to the Kareng fund. The Kareng Fund aids Oregon crafters and artisans experiencing a career-threatening crisis. -

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

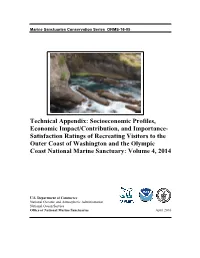

Technical Appendix

Marine Sanctuaries Conservation Series ONMS-16-05 Technical Appendix: Socioeconomic Profiles, Economic Impact/Contribution, and Importance- Satisfaction Ratings of Recreating Visitors to the Outer Coast of Washington and the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary: Volume 4, 2014 U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Ocean Service Office of National Marine Sanctuaries April 2016 About the Marine Sanctuaries Conservation Series The Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, serves as the trustee for a system of 14 marine protected areas encompassing more than 170,000 square miles of ocean and Great Lakes waters. The 13 national marine sanctuaries and one marine national monument within the National Marine Sanctuary System represent areas of America’s ocean and Great Lakes environment that are of special national significance. Within their waters, giant humpback whales breed and calve their young, coral colonies flourish, and shipwrecks tell stories of our maritime history. Habitats include beautiful coral reefs, lush kelp forests, whale migrations corridors, spectacular deep-sea canyons, and underwater archaeological sites. These special places also provide homes to thousands of unique or endangered species and are important to America’s cultural heritage. Sites range in size from one square mile to almost 140,000 square miles and serve as natural classrooms, cherished recreational spots, and are home to valuable commercial industries. Because of considerable differences in settings, resources, and threats, each marine sanctuary has a tailored management plan. Conservation, education, research, monitoring and enforcement programs vary accordingly. The integration of these programs is fundamental to marine protected area management. -

Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site

GWAII HAANAS NATIONAL PARK RESERVE AND HAIDA HERITAGE SITE Management Plan for the Terrestrial Area A Pacific coast wilderness in Haida Gwaii — the Queen Charlotte Islands. Protected through the cooperation of the Government of Canada and the Council of the Haida Nation Produced by the ARCHIPELAGO MANAGEMENT BOARD GWAII HAANAS STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE TERRESTRIAL AREA FOREWORD n January of 1993, the Government of The Council of the Haida Nation and the I Canada and the Council of the Haida Nation Government of Canada agree and support the signed the Gwaii Haanas Agreement. In this contents of this plan and will work together document, both parties stated their commitment through the Archipelago Management Board to the protection of Gwaii Haanas, one of the to implement the plan’s recommendations. world’s great natural and cultural treasures. A By supporting this plan, the two parties part of this agreement describes the cooperative assert their belief in the value and benefit of management procedures, including establish- cooperative management and preservation of ment of the Archipelago Management Board. Gwaii Haanas. This management plan, produced by the Archipelago Management Board in consultation with the public, sets out strategic objectives Approved by: for appropriate use and protection of Gwaii Haanas. The plan not only provides comprehensive strategic direction for managing ○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Gwaii Haanas, but it also serves as an example ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ for the Government of Canada of cooperative effort and marks an important milestone in the relationships of Canada and the Haida Nation. ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ for the Council of the Haida Nation 3i CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 2 1.1 Description of Gwaii Haanas......................................................... -

Inland Lifeways of Haida Gwaii 400-1700 CE

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2015-02-13 Inland Lifeways of Haida Gwaii 400-1700 CE Church, Karen Church, K. (2015). Inland Lifeways of Haida Gwaii 400-1700 CE (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/26535 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/2107 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Inland Lifeways of Haida Gwaii 400-1700 CE A Landscape Archaeological Study by Karen Church A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACLUTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ARCHAEOLOGY CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2015 © Karen Church 2015 Abstract The inland lifeways of the northwest Pacific archipelago, Xaadlaa gwaayee (Haida Gwaii, British Columbia), have not been the subject of intensive archaeological inquiry. The routes of precontact inland trails are no longer known well due to the decimation of the local population in the 18th and 19th centuries. Industrial logging is threatening to destroy archaeological evidence of the inland trail network, and therefore this inquiry is timely. The largest and most topographically diverse island, Graham, has been the subject of many archaeological impact assessments that have documented hundreds of archaeological sites, most of them containing culturally modified trees. -

On the Haida Gwaii, 1966-7990

THE HAIDA STRUGGLE FOR AUTONOMY ON THE HAIDA GWAII, 1966-7990. BY NORMAN L. KLIPPENSTEIN A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Departrnent of Anthropology University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba @ February,7997 Bib{iothèque na(ionate E*E 5¡3ä1!:,"* du Canada Canadian fheses S€rv¡ce Serv'tce des thèSës canacfienhes O(awa. Cenåda K¡A ON4 The, agthor has granted.an inevocable non- exclus¡ve L'autzuraaccordé une ticence inévocable licence al.fowiqg üte Naüonal Ubrary et of canada.tg non exdusive permetÞnt ä la B{-bl¡oürèquã reproduce. Ëu{,; d;ü,6ut" or sefl coptgs of his/her nationale du Canada de reproduïre, prêtbr, thes¡s by any means afrd ln cfrsbibuerou for* or vendre ¿escobres ãää thèse 3y fofinaE fialdng-ft¡s ft"s¡";*ilrbt queQue ro tnterested de mar¡îère et sous qu"lquã forme persons, qu9 ce_ soit porr mettre des eiemòlaîres de cette thèse à la disposition des pe.sonn", intéressées. The author retains ow¡ership of the copyright in his/her thesis. L'auteur conseflre ta propriété du dro{t d,auteur . Neittrei tf,e nãL¡s no, qui protege substantial extracts sathèse. N¡ta thèse n¡ ¿esãxma¡ts from it may Oepr¡nted or de celleci otherwise reproduced withoút trìs7Àu. pen -substantiels ne Ooivent être mission. imprimés ou autrement reproduitr-"ä" autorisation- "on ISBb¡ Ø-315-76785-5 \-anaC[a/'\ - tr.r THE HAIDA STRUGGLE FOR AUTONOMY ON THE HAIDA GWATI, 1966-1990 BY NORM,AN L. -

The Ballad of the Bold Northwestman: an Incident

THE BALLAD OF THE BOLD NORTHWESTMAN : AN INCIDENT IN THE LIFE OF CAPTAIN JOHN KENDRICK* The ballad of the Bold Northwestman, once a prime favorite in the forecastles of the maritime trading vessels, gives an account of an incident in the life of one of those whose name was well known in New England ships and New England homes-Captain John Kendrick. The mere fact that the ballad does not mention his name may almost be taken as evidence to SUppOlt this state ment; it certainly was not omitted for the sake of rhyme or metre, with both of which the balladist takes more than the usual liberties. Captain John Kendrick commanded the expedition of the Columbia and the Washington, the first vessels from Boston to engage in the maritime fur-trade. In July, 1789, (for what reason is not as yet ·definitely known) he handed over the ship Columbia to Captain Gray and for the remainder of his life sailed the little sloop, Wash ington. In her he reached China in January 1790. There he trans formed her into a brig (or, more probably, a brigantine) and sailed again for the Northwest Coast in March 1791. In June 1791 the Indians of Houston Stewart Channel, in the southern part of Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia, attempted to capture his little vessel. This waterway has borne many names; the maritime traders lefer to it as Koyah's, Coyah's, Coyour's, after the Indian chief of the locality who figures in the ballad, though not by name. Captain Robert Gray, in June, 1789, when in command of the sloop JlVash ington, had called it Barrell Sound, after his principal owner. -

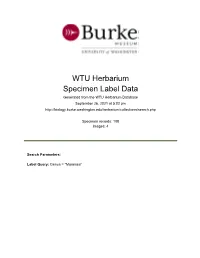

WTU Herbarium Specimen Label Data

WTU Herbarium Specimen Label Data Generated from the WTU Herbarium Database September 26, 2021 at 5:02 pm http://biology.burke.washington.edu/herbarium/collections/search.php Specimen records: 108 Images: 4 Search Parameters: Label Query: Genus = "Moneses" Ericaceae Ericaceae Moneses uniflora (L.) A. Gray Moneses uniflora (L.) A. Gray U.S.A., OREGON, WALLOWA COUNTY: U.S.A., WASHINGTON, JEFFERSON COUNTY: Wallowa-Whitman National Forest. Trail at end of Lostine River [No locality given on label]. Road, approximately 0.25 mile to the east; up Lostine River; off trail. Elev. 200 ft. Elev. 5367 ft. 47.71098°, -123.66793°; WGS 84, uncertainty: 67000 m., Source: 45° 14.935' N, 117° 22.534' W GeoLocate, Georef'd by WTU Staff Conifer forest wetland; with fir, spruce. Phenology: Flowers. Origin: Bench above the ocean. On a mossy log. Phenology: Flowers. Native. Origin: Native. Jessie Johanson 02-160 21 Jul 2002 I. C. Otis 1266 16 May 1924 with Joe Johanson, David Giblin, Ken Davis, Robert Goff, Cindy Spurgeon WTU-27574 WTU-360478 Ericaceae Ericaceae Moneses uniflora (L.) A. Gray Moneses uniflora (L.) A. Gray U.S.A., WASHINGTON, KING COUNTY: Kings Lake, 1 mile west of Boyle Lake, northeast of Snoqualmie U.S.A., OREGON, WALLOWA COUNTY: Falls. Wallowa-Whitman National Forest. Hurricane Creek Canyon, along Elev. 951 ft. trail. T24N R8E; NAD 27, uncertainty: 200 m., Source: Georeferenced, Elev. 5441 ft. Georef'd by WTU Staff 45° 17.583' N, 117° 18.495' W Perennial; in fruit. Under Tsuga heterophylla with Pteridium Open meadow bordered by mixed conifer forest with openings. -

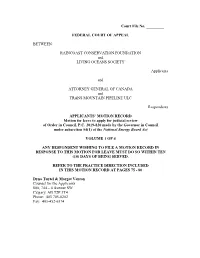

Raincoast & LOS Application for Leave TM Reconsideration Vol 1

Court File No. _________ FEDERAL COURT OF APPEAL BETWEEN: RAINCOAST CONSERVATION FOUNDATION and LIVING OCEANS SOCIETY Applicants and ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA and TRANS MOUNTAIN PIPELINE ULC Respondents APPLICANTS’ MOTION RECORD Motion for leave to apply for judicial review of Order in Council, P.C. 2019-820 made by the Governor in Council under subsection 54(1) of the National Energy Board Act VOLUME 1 OF 4 ANY RESPONDENT WISHING TO FILE A MOTION RECORD IN RESPONSE TO THIS MOTION FOR LEAVE MUST DO SO WITHIN TEN (10) DAYS OF BEING SERVED. REFER TO THE PRACTICE DIRECTION INCLUDED IN THIS MOTION RECORD AT PAGES 75 - 80 Dyna Tuytel & Margot Venton Counsel for the Applicants 800, 744 – 4 Avenue SW Calgary, AB T2P 3T4 Phone: 403 705-0202 Fax: 403-452-6574 TO: FEDERAL COURT OF APPEAL 3rd Floor, 635 – 8 Avenue SW Calgary, AB T2P 3M3 AND TO: ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA c/o Department of Justice Canada Suite 601. 606 – 4 Street SW Calgary, AB T2P 1T1 Tel: 403 292-6813 Fax: 403 299-3507 TRANS MOUNTAIN PIPELINE ULC c/o Osler, Haskin & Harcourt LLP Suite 2500, TransCanada Tower 450 – 1 Street Sw Calgary, AB T2P 5H1 Tel: (403) 260-7003/7038 Fax: (403) 260-7024 NATIONAL ENERGY BOARD 517 – 10 Avenue SW Calgary. AB T2R 0A8 Tel: 403 292-4800 Fax: 403 292-5503 TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 Tab Document Page 1 Notice of Motion 1 2 Order in Council, P.C. 2019-820, published in the Canada Gazette, Part I, 9 dated June 22, 2019 3 Practice Direction of Sharlow J.A., Applications for leave to apply for 75 judicial review under subsection 55(1) of the National Energy -

ENVIRONMENTAL POLITICS on HAIDA GWAII by Michael Dean A

“WHAT THEY ARE DOING TO THE LAND, THEY ARE DOING TO US”: ENVIRONMENTAL POLITICS ON HAIDA GWAII by Michael Dean A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (VANCOUVER) October 2009 © Michael Dean ABSTRACT This paper discusses the development of Native environmental politics on Haida Gwaii, also known as the Queen Charlotte Islands, since the late 1970’s. During that time, concerns among the Haida about the impacts of industrial logging on their culture led to the emergence of a sustained, innovative challenge to the existing regime of resource extraction on the islands as well as the larger colonial structures on which it was premised. As a result, environmental activism became a means for the Haida to pursue decolonization outside the official channels of the land claims process. In particular this paper focuses on the conflict surrounding logging in the area of South Moresby Island culminating in the creation of the Gwaii Haanas National Park, which was the first National Park to be co-managed by the Government of Canada and an indigenous nation. By tracing the development of environmental activism on Haida Gwaii it contributes to an understanding of the ways that recent Native environmental movements have formulated indigenous identity and drawn on cultural traditions as well as their experience of colonialism. It also contributes to debates surrounding co-management and TEK by showing how the development of Haida environmental management structures occurred in conjunction with the development of a Haida environmental politics without which it would not have been capable of delivering on its liberatory promise. -

And Others Small Scale Marine Fisheries

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 243 658 SE 044 389 AUTHOR Martinson, Steven; And OtherS TITLE Small Scale Marine Fisheries: An ExtensionTraining Manual. TR-30. INSTITUTION Peace Corps, Washington, DC., Office of Program Development. SPONS AGENCY 'Peace Corps, Washington, DC. InformationCollection and Exchange Div. PUB DATE Apr 83 NOTE 578p.; Prepared by Technos Corp., San Juan, Puerto RiCO. PUB TYPE Guides = Classroom Use - Guides (ForTeachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF03/PC24 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Developing Nations; *Fisheries; *Learning Activities; Marine Biology; Postsecondary Education; Science Education; *Skill Development; Technology; *Training Methods; *Training Objectiyes IDENTIFIERS *Peace Corps ABSTRACT This manual is designed for use in_a preservice training program 'for prospective volunteers whose PeaceCorps service Will be spent working with small-scale artisanalfighing communities in developing nations. The program consists of8'weeks of intensive training_to develop competencies in marinefisheries technology and fisheries extension work and in the ability to transferknowledge and skills. The manual includes an overview of the program,lists of program goals, information onstarting the program, lists of references and materialt needed,_tips on conductingthe program, and the complete 111 training sessions.Provided for each session-are: (1) session goals; (2) one or more exercisesdirected toward meeting these goals; (3) total time required to complete thesession or exercise; (4) overview statement describing the purposeof the session or exercise; (5) procedures andactivities (sequenced in time steps that describe what trainer andparticipants are required to do at a particular point in theprogram); (6) list of materials and equipment needed; and, when applicable, (7) trainer notes.Although each session builds toward or from the -ones) preceding and following it, individual sessions can be usedindependently with minor modification.